Mad Men

2007 - United StatesReview - JWR

Although critics loved Mad Men, hailing it as one of the great achievements of 21st Century television, alongside the likes of The Sopranos and The Wire, it sometimes struggled to find the audience it deserved.

It is easy to understand both sides of that apparent contradiction. The show is a beautifully crafted piece of work, no question. However, the defining feature of all great craftsmanship, and of its appreciation, is attention to detail. You really need to concentrate when you watch Mad Men. That is not something most television viewers are famous for doing.

It may be necessary to watch it more than once to get the full significance of a throwaway line, a brief facial expression, something happening in the background, or a meaningful cut. This is not a show that could have been made in the days of live television. It requires a playback facility or a cinematic level of focus - ideally both.

Those unwilling to invest in it fully are, frankly, unlikely to enjoy it very much. It involves spending time with people who are, for the most part, not very pleasant, and in a time and place - 1960s Madison Avenue, New York - which is also portrayed as rather unpleasant.

The point is that the positive image we have of the Sixties today - the bright colours, the music, the casual affluence, "free love," Flower Power, and so on - is just that, an image, specifically an artificial picture painted by the big advertising firms of Madison Avenue, the self styled "Mad Men."

Of course, this leads on to the other point, that Mad Men the show is itself an image - the image of the making of an image - and therefore, like the first image, artificial and unreliable. So we find ourselves engaging with Big Ideas about the nature of reality and therefore of personal identity. The "Mad" in "Mad Men" refers to Madison Avenue not to insanity, but there is a double meaning in that the protagonists, while ruthlessly practical, struggle with deep psychological and philosophical problems. They all want to know who they are. It is a question everyone asks. In the end, the two principal protagonists are given an unusually straightforward answer: they are ad men, that really is who they are, even if one happens to be a woman.

The other is very much a man, a tower of unreconstructed masculinity played without restraint by John Hamm. Yet that is about all we can say about him with certainty, for everything about "Don Draper" - including his name - is a lie. He is therefore a human metaphor for all those uncertainties about the nature of reality and identity, and for the advertising industry in particular. The big question is always "Who is Don Draper?" The man himself has no idea.

On the surface, he is a Byronesque hero. His good looks - he is compared with James Garner in the dialogue, but appears closer to George Lazenby, with a touch of Sean Connery - give him an arrogance that enables him to dominate men and women alike. There is sometimes a cruelty in his animalistic exploitation of this power over others.

Yet, beneath that surface, he is, from start to finish, a very frightened man. Rewatching certain scenes after finding out certain things later, one realises they are were not at all as one remembered them. There is a subtext to everything. "Draper" lives in a constant fear of being found out. He has a case of "imposter syndrome" that is particularly acute because he really is an imposter.

He therefore finds a natural home in sales, then advertising, where he turns into a brilliant "creative director." The scenes that show the development of his ideas are especially outstanding. In his way, he is a genuine artist. We see him rise from a comfortable middle class life in the suburbs, with all its suffocation, to considerable wealth - and high style. This is counterpointed by flashbacks to his poverty stricken childhood. There is considerable satisfaction in seeing him succeed, and acquire the gaudy trappings of Sixties affluence, except that this is, for all its cynicism, a strangely old fashioned morality tale, and the moral here is that money does not buy happiness.

His fear of discovery remains, but at the same time he develops a self destructive streak. It can be quite frustrating for the viewer who begins to care about him when "Draper" seems to have found the perfect life, with the perfect fantasy woman, only to spoil it through irrational self indulgence. Does he feel he does not deserve it? Or does he doubt the reality of it all? The quest for authenticity in his life of lies remains a constant theme.

The second main protagonist, Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss), is in many ways, the Anti-Draper. She is the most authentic and grounded of the regular characters, and the most likeable. "Draper" promotes her from the typing pool to copywriter, largely because of her appreciation of what motivates women - a rare commodity in male dominated Madison Avenue. She becomes his perky apprentice, but, just as we begin to think we know where this is going, she becomes increasingly aware of his limitations and asserts her independence. Yet, in the process, she is hardened by experience - and becomes more like him than she might like to think.

So there are two main plotlines in Mad Men, the major "Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall and Rise(?) of Don Draper," and, running in parallel, the minor "Coming of Age of Peggy Olson, the First Woman Creative Director on Madison Avenue." We never get to see her achieve that, her great secret ambition, by the time the series leaves her in 1970, but by then we are fairly certain that she will.

Around these two main story arcs about a dozen other protagonists and supporting players have their own character arcs, some more satisfying than others.

The most memorable is the hard drinking, womanizing Roger Sterling, who discovers "Draper," and thereafter serves as his mentor and occasional best friend. Sterling, played in style by John Slattery, is a second generation ad man, and a moral vacuum with enormous charm who gets most of the best lines. There are moments when he questions his life, but only moments. He never actually gets around to changing.

This is in spite of two heart attacks - back in the day when one was still considered practically a death sentence. There is certainly a sense of valediction about his scenes at that point. Then he gets better, carries on much as before, and the subject is rarely mentioned again.

The original plan was to bring in Slattery, an actor very much in demand, to help get the show off the ground as a guest star and then kill off the character fairly quickly. However, the producers soon realised that they were on to a good thing and Slattery was kept on as a regular until the show ended after seven seasons.

Pete Campbell is an apprentice Roger Sterling - minus the charm - but obviously sees "Draper" more as his role model. Indeed, there are moments when he sees him almost as a substitute father, only to be crushed when he realises "Draper" does not care. So the two develop a curious love-hate relationship, even if the emotions are nearly all on Campbell's part - there is little evidence that "Draper" thinks about it much at all.

The descendent of decayed New York aristocracy, Campbell is in many ways an odious creature. He copies all the worst things about "Draper," most significantly the appalling way he treats women, but has none of his talent. It is therefore greatly to the credit of Vincent Kartheiser, who plays him, that we nevertheless feel moments of sympathy when we get glimpses of what made him what he is and of the lonely desperation that drives him. We wonder if, in an environment less toxic than Madison Avenue, he might not be a decent man. We end up hoping he gets the chance to find out.

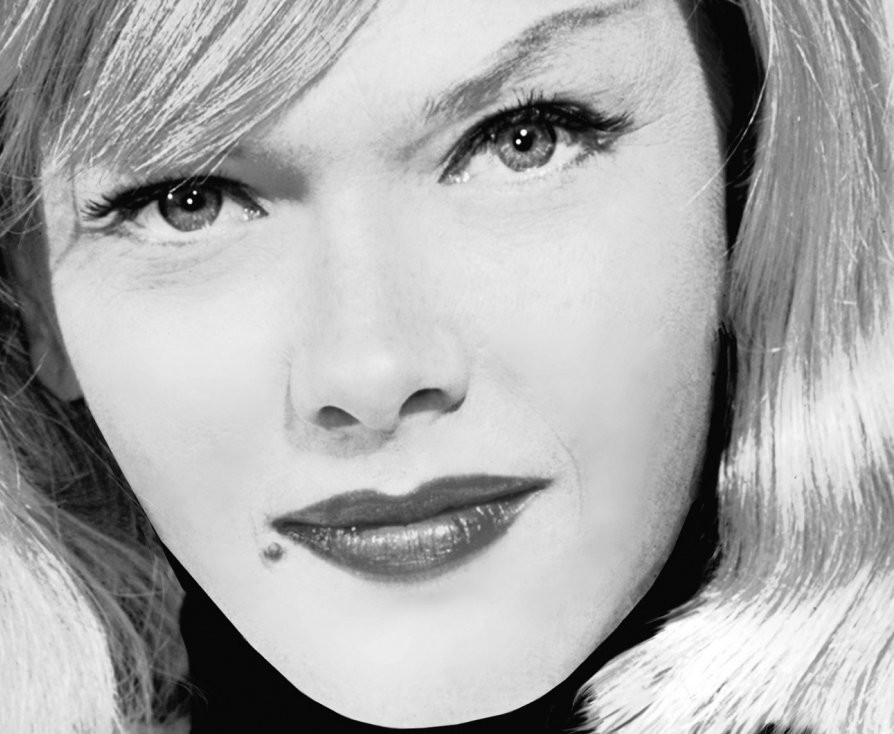

Given how handsome he is, it is to be expected that "Draper" has a beautiful wife, and January Jones plays Betty "Draper" as a young Grace Kelly. As a married couple, the only thing they share is the sense of entitlement that tends to come with good looks. However, unlike her husband, Betty has no secret fear or uncertainty to balance it. She is initially a selfish young woman with little capacity for reflection. "Draper" is harsh but not inaccurate when he compares her with a spoilt child. Theirs is a marriage in which both pretend to be playing the roles expected of them without really understanding why.

This does not excuse the way he treats her - as he treats almost all the women in his life, very badly, because he can. She responds badly - childishly - in her turn. Yet, in the end, the viewer finds an unexpected pity for her, and perhaps even an admiration. The child grows up.

Betty's polar opposite is the most emotionally mature character, which is not exactly saying a great deal in this company. Joan Holloway is every businessman's dream secretary. This is not just because she is physically stunning - even if she is, the costume department making the very most of actress Christina Hendricks' magnificent figure. The really attractive thing about Joan from a businessman's point of view is her apparently limitless competence. She is the person who really runs the Sterling Cooper advertising agency - a point underlined in a great scene in which she makes a perfectly timed entrance in the midst of chaos, a chaos which ends almost immediately as she takes command.

She is like a sexy Sergeant Major in a tight fitting dress. She knows exactly how to exploit her appearance, and has no qualms about doing so, but all is a means to an end. Joan is proud of the status she has attained and demands that it is respected. She proves a highly effective operator in what is very much a man's world and it is no surprise that she becomes a successful businesswoman in her own right.

The most mature character in terms of years - and, occasionally, wisdom - is Bertram Cooper, senior partner of the Sterling Cooper agency. In a wonderful casting 'coup,' Cooper is played by Robert Morse, best known as the star of the definitive1960s satire on American corporate life, 'How to Succeed In Business Without Really Trying.' To add to the irony, those familiar with the film or the stage version of that musical may recall that the book on which it is supposedly based advises that there is one type of work the ambitious businessman should avoid at all costs - advertising!

Morse is great fun, adding value to every scene in which he appears, even if he just sits doing nothing in the lobby. One of the highlights of the final season is when he is given a rather surreal song and dance number in tribute to his earlier career in musicals.

Among the many interesting supporting character arcs, that of Lane Pryce, an honourable but out of his depth Englishman played by the excellent Jared Harris, stands out as the most poignant. Harris also served as a director on the series.

An almost unrecognisable Harry Hamlin, in thick rimmed period glasses, is a hissable villain as a number cruncher - even if he is basically right about most things.

While the cast as a whole was faultless, often brilliant, there is still a danger that Mad Men will be remembered less for its drama than for its production. This is a rare example of an American show that one could watch with the sound turned right down just to enjoy the look of the thing - not that one should, because then one would be missing something worth hearing as well as seeing. The costumes, sets, props, and art departments were given the sort of challenge that brought them into their lines of work in the first place, and they really went to Town.

Their task was to recreate the Sixties, year by year, at the centre of high fashion. They seem to have rather enjoyed themselves in the process. A great deal of effort obviously went into the research, and, while there are always people out there who can pick up on tiny points of detail, there is no doubting the overall sense of visual authenticity.

(One excusable lapse in that authenticity was the use of well known locations in Los Angeles, where the show was made, for the places in New York, and, in one occasion, Rome, where it is set. On the whole, LA plays NY surprisingly well and 'La Dolce Vita' Rome even better.)

The Sixties is remembered fondly as the Decade of Colour. Television was a major factor in that. People who bought colour televisions wanted to get their money's worth. So, in turn, did studios and broadcasters who invested in the new colour technology. They expected colours to be vibrant and distinct. This impacted in turn on fashion as people copied what they saw on television.

If the result was often garish, it was also bright and cheerful, so 'Mad Men' is a welcome return to the days when colour television really meant something.

Joan's ever changing wardrobe is a special delight, and not just because Christina Hendricks appears in it. She looks at her best in bright, lush "cold colours" - purple, blue, and green - offsetting her red hair. There is no pretence of subtlety.

Yet look closely and you will note something that only those who were really there can tell you about the Sixties: the clothes that looked so splendid at a distance were actually made of artificial fabrics that were often of very low quality by today's standards. Polyester was not only permissible but fashionable. The trendy looking furniture and fittings also tended to be cheaply made. This is itself a metaphor for the Decade and is reflected accurately in Mad Men.

Yet this visual accuracy is not always matched by a similar authenticity in the writing. Here two great weaknesses keep Mad Men from absolute perfection.

The first is the weakness common to most "historical drama" - for which purpose the Sixties now counts as history. This is the tendency to look back at the past and judge it by the standards of the present.

So Mad Men invites us to look back at certain aspects of the Sixties - from racism and the treatment of women to heavy drinking at work and casual littering - with horror and disapproval so that we can congratulate ourselves on how superior we are to our parents and grandparents.

This can leave a bit of a bad taste. While it is a useful exercise to reflect on cultural changes over time, this should lead to humility rather than smugness. It is easy to sneer at both the conservatism of much of America in the Sixties and the subsequent excesses of the Counterculture in response, but are we really in a position to judge either? Whatever else, the former delivered a high degree of social cohesion - at least outside those areas divided by racial conflict - while the latter was the product of a sincere passion to change the world for the better. Could we not use a bit more of both in our world today? While most would agree we have made progress in some other respects, perhaps we have lost something important along the way which Mad Men fails to acknowledge.

This leads to the second great weakness in the writing, another which is very common. Any historical drama is necessarily selective in its presentation of the facts: there is no time to present a full and fair picture. That has to be accepted. Yet in writing to an agenda which wishes to give a certain view of the past, Mad Men excludes everything that contradicts it, so that even if what is included is accurate, the viewer is given a picture that is partial and therefore misleading. So its accuracy in minor points of detail is not reflected in the authenticity of the landscape of America between 1960 and 1970 which it aspires to be.

Many examples of this could be cited, but to sum it up very briefly, Mad Men tends to downplay the racism of America at that time and exaggerate the misogyny. Thus an accurate representation of the reactions of New Yorkers to the murder of Martin Luther King would probably oblige at least some of the supposedly sympathetic protagonists to say things that simply cannot be said on television these days. On the other hand, the fact that almost every married character commits adultery ignores the deep cultural conservatism of America, then and now. Also ignored is a very strong American tradition of courtesy towards women, which was, in those days, even stronger.

In strict fairness, New York is not America, nor is Madison Avenue New York, but some who were in Madison Avenue at that time have been very critical of the inauthenticity of Mad Men. There were successful women copywriters in New York long before Peggy Olson. That Madison Avenue was basically a Boy's Club is not really in dispute, but it was not exclusively so, nor was it a permanent fraternity party. It was a very serious place of business.

Anyway, Mad Men ceases to be about Madison Avenue when "Draper" goes off to look for America, setting up a beautifully subversive ending.

The last we see of him is a gentle smile crossing his face in a group meditation at a "New Age" commune. Has he found inner peace in rejecting the whole culture of consumerism?

The key to answering that question is knowing that the famous advertisement that follows, and which ends the series, was produced the following year by McCann Erickson, the firm by which he was then employed.

For the Sixties - including the Counterculture, the Age of Aquarius, Flower Power, Hippies, the Summer of Love, Woodstock, and all that - were themselves commodified in the end, and became just one more product to be sold and to be used in selling by Madison Avenue.

As for "Draper," like they say, he went looking for America and found himself - still an ad man.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 24th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.