Nightingales

1990 - United KingdomWhen Nightingales arrived on Channel 4 in 1990, it felt like it had wandered in from another dimension. While most sitcoms were still rooted in familiar living rooms and pubs, this one locked itself inside a deserted office block and more or less refused to leave. In fact, the action rarely strays beyond a single room. It’s less about what happens and more about what’s said — and what very, very strange things occasionally materialise during the night shift.

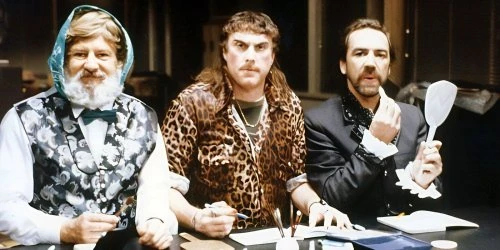

The premise is disarmingly simple: three bored nightwatchmen killing time. But the execution is anything but ordinary. Robert Lindsay (GBH) plays Carter, a pompous, permanently frustrated pseudo-intellectual who clearly believes he was destined for greater things. David Threlfall’s (Scum) “Ding Dong” Bell is a dim, vaguely thuggish presence who hangs on Carter’s every word, even when he doesn’t understand it. Then there’s James Ellis as Sarge, a relentlessly cheerful veteran whose old-fashioned optimism spoofs the world-weary character he played for many years in Z Cars. Completing the quartet — in a manner of speaking — is Smith, who is dead for the entirety of the first series. The others simply keep his body in the building so they can continue claiming his wages. That’s the sort of show this is.

Written by Paul Makin and produced by Alomo Productions, Nightingales throws out traditional sitcom realism and happily constructs its own surreal universe. The dialogue is often naturalistic and oddly thoughtful, but it constantly rubs up against absurd plots and theatrical in-jokes. The trio are obsessed with Shakespeare and Harold Pinter, a running gag that feels both affectionate and gently mocking. One Christmas episode features a heavily pregnant woman named Mary who insists she is absolutely not an allegory, and somehow ends with Pinter cycling away from their party on a tandem with the Pope. It’s never explained, and that’s entirely the point.

Across its thirteen episodes, which aired between 1990 and 1993 (with a long delay before the second series thanks to Channel 4 executive Seamus Cassidy’s doubts about early scripts), the show embraces the bizarre without blinking. There’s a real werewolf — luckily friendly. Carter and Bell briefly reinvent themselves as Shakespearean villains. A burglar calmly produces evidence that he is the illegitimate son of all three watchmen. And in the final episode, doppelgängers arrive to murder and replace them just as a new security system threatens their jobs. By the end, it’s left deliberately unclear whether the “real” trio survive.

The second series feels more confident and developed, leaning further into the strange rhythms and theatrical tone. The comparisons that would later be made to The League of Gentlemen and Little Britain are understandable, but Nightingales is arguably more self-contained and less sketch-driven — almost Beckett-like in its sense of stasis and repetition. Even the theme tune, a wistful rendition of “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square” sung by Lindsay, adds to the oddly melancholic atmosphere.

It never found a mainstream audience, and a 1992 American pilot directed by James Burrows and starring Trevor Eve failed to develop into a full series. Perhaps the show was simply too peculiar, too theatrical, too stubbornly itself to travel easily.

What makes Nightingales endure is that it commits completely to its strangeness. It’s surreal but never smug, intellectual but never entirely inaccessible. Beneath the absurdity there’s a genuine sense of camaraderie and loneliness, three men stuck in a fluorescent-lit limbo talking their way through the night. It’s the kind of sitcom where almost nothing happens, yet somehow anything can — and often does.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 16th, 2026. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.