Samurai Rabbit: The Usagi Chronicles

2022 - United States“a great children's show in which even parents might find something to enjoy.”

Samurai Rabbit review by John Winterson Richards

The full title of the Netflix animation Samurai Rabbit is in fact Samurai Rabbit: The Usagi Chronicles, which may be why it is not as well known as it deserves to be. The longer version ties it to its source material, Usagi Yojimbo, a "comic book" with a much more adult tone than what is essentially a children's show. This gives it something of a split personality, which is interesting from a viewer's perspective but a headache in terms of marketing.

Its story begins in 1982, when Sergio Aragones, best known for his contributions to Mad Magazine and as, allegedly, "the world's fastest cartoonist," introduced the world to the well-meaning but dim-witted and lethal swordsman Groo the Wanderer. Obviously much influenced by the then-recently released feature film Conan the Barbarian, the comic book series was a parody of the sword and sorcery genre at its zenith. As often happens, the parody became the very thing it set out to parody as, over the years, Groo the Wanderer developed its own detailed fantasy world. The busy Aragones was assisted in this by a strong team made up of the television writer Mark Evanier, the colourist Tom Luth, and the letterist Stan Sakai. (Do not ask how I know all this. It embarrasses me a little that I am writing most of it from memory).

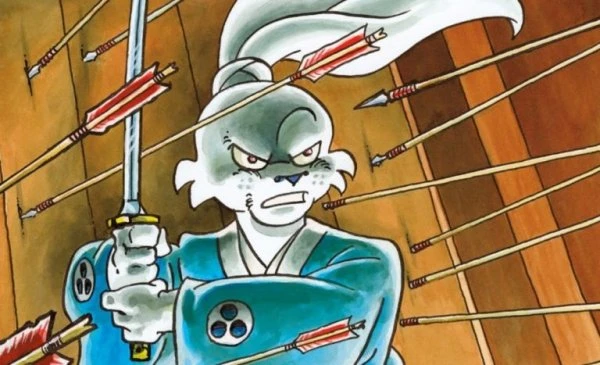

An accomplished writer and cartoonist in his own right, Sakai soon began considering a project about a wandering swordsman on similar lines, except based on his own Japanese heritage rather than on fantasy. He was thinking in terms of a more serious tone until, sketching a samurai rabbit on a whim, he decided to soften his approach by making his characters anthropomorphic animals. The result was another long-running comic book series, Usagi Yojimbo. "Usagi" is Japanese for rabbit and "Yojimbo," as fans of Kurosawa's classic feature film of that name will know, means bodyguard. Usagi Yojimbo is in fact filled with knowing references to the films of Kurosawa, Inagaki, Misumi, Mizoguchi, and the whole chanbara or samurai genre. The protagonist's name is actually Miyamoto Usagi, after Miyamoto Musashi, the greatest of all samurai swordsmen and the author of The Book of Five Rings.

Sakai continued to do the lettering on Groo and Aragones sometimes contributed to Usagi Yojimbo. Tom Luth did the colouring for both projects. There are also obvious parallels between Usagi Yojimbo and the similarly themed Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and there were indeed "cross overs" between the two comic book series – although TMNT are now somewhat tainted by having sold out big time to Hollywood they are still a comic book classic. Nevertheless, Usagi Yojimbo retained much of the seriousness that Sakai originally had in mind before he introduced the animal characters and was prepared to take them to some very, very dark places. Those familiar with the comic books will know what I mean. Those who love the sweetness of the television show really do not want to go there, trust me.

For it cannot be stressed enough that Samurai Rabbit is very much the children's version of Usagi Yojimbo. The protagonist is not Miyamoto Usagi himself but a distant descendant, Yuichi Usagi, living in a futuristic Neo Edo which retains some aspects of samurai culture in a high-tech modern city - a scenario for which Sakai himself prepared the way in a spin-off series of the comic books called Space Usagi. A number of the supporting characters from the comic books also turn up in the show but in very different forms and they are treated far more kindly. Miyamoto Usagi himself appears mainly in flashbacks in the hand-drawn style of the comic books which hint at their more explicit violence.

This lighter tone to the television version was undoubtedly the right way to go. A direct adaptation, with animal characters being killed on screen, would be simply unwatchable. However, the price of this is that many hardcore fans of the comic books felt the adaptation was untrue to them. Although they are not numerous, the existing fan base is always an essential part of the target market for an intellectual property-based project, and, of course, disgruntled fans are disproportionately likely to make their feelings known online.

It did not help that the show did not get off to the strongest of all starts. Our protagonist, Usagi, comes across at first as an impulsive and self-centred teenager, which is not particularly appealing. That is, of course, the whole point. This is a bildungsroman, the story of how our long-eared hero begins to grow up a bit.

In a storyline ripped straight out of The Three Musketeers, Usagi leaves the family farm for the big city to seek his fortune and is no sooner there than he falls foul of three warriors who are destined to become his friends. Gen is a bounty-hunting rhinoceros whose tough skin hides a sensitive soul. Chizu is a ninja cat beginning to question her life choices. Kitsune is a puppeteer fox with larcenous tendencies.

The de Treville of these unlikely Musketeers is Tetsujin, the Guardian of the Ki-Stone, the mysterious source of all the city's power. That the apparently slow bear has a degree in quantum physics is not the only surprising thing we learn about him.

Usagi's Planchet is Spot, his pet Tokage, who steals every scene in which he appears, even in the background. The Tokage are tiny dinosaurs who are pretending to be lizards. Sadly, they are fictional: I know because I looked them up because I wanted one. Spot's affection, loyalty and playfulness, combined with his astonishing range of chirrups and eeps, make him irresistible.

He is the cutest in a show that thrives on cuteness. There are times when the whole thing seems to be a satire on the Japanese cult of extreme cuteness, but then there are other times when it seems to have given up on the satire and simply jumped head-first into a vat of sugar. Someone in the production seems to have set out to prove that anything can be cute - furniture, hats, a chirping mechanical ball that turns into a Zoomer war robot, the friendly but questionably competent staff of a hospital where Gen spends a lot of time, a ceremonial vehicle, what appears to be an umbrella with a long tongue, homicidal ninja kittens. (To be honest the last were never going to be much of a challenge in terms of cuteness).

Usagi meets, and befriends, these characters as his social circle begins to expand. It is not confined to the cute. Most unusually, good is found even in the ugly as enemies become friends. Usagi even forms working alliances with the three main gangs of Neo Edo; the well-choreographed moles whose finger snapping is straight out of West Side Story; the militaristic Bat Squadron; and the Neko Ninjas. "Neko" is Japanese for cat, and it should be no surprise that cats turn out to be ninjas. Most cat owners/servants have long suspected as much.

The script therefore has important things to say about friendship, co-operation, tolerance, and learning. Good values for a children's show, without being preachy. Many lines are oddly quotable. The plotting is tight, with no obvious holes, which is unusual these days. The characters are well constructed and consistent. Even supporting characters have proper arcs. The principals are all likeable, the more so because they are all imperfect. The interplay between them as they develop cautious friendships is realistic and as dramatically interesting as the action set pieces. Those set pieces are short but frequent, which is far more entertaining than the current fashion for building up to big events that go on too long. There are a lot of genuinely amusing moments, in the dialogue, in visual gags, and in the deft combination of the two, but the humour remains unforced. The voice actors are well cast, especially Sumalee Montano, apparently channelling Dame Helen Mirren as Usagi's slightly exasperated sensei or mentor.

The quality of the animation, produced by the French Gaumont with the Indian based 88 Pictures doing much of the legwork, is consistently outstanding. It has the imagination of East Asian anime but without the shortcuts. It maintains a luxuriant, Gallic charm - the French seem to be the undisputed masters of artistic animation at the moment, as befits the nation that gave the world Impressionism and the bande dessinee. It uses light and colour very effectively. Both the landscapes and cityscapes are evocative of Japan in best Studio Ghibli style. The show has a wonderful eye for detail throughout, so it might be worth watching twice to pick up on what one could easily have missed the first time. The looks of the characters are expressive and distinct. There always seems to be something going on.

Indeed, the whole thing is positively cinematic, the sort of thing Disney and Pixar might have produced before they started getting lazy and taking their customers for granted.

It is therefore rather surprising that Samurai Rabbit is not a cult hit like Arcane or The Legend of Vox Machina or Invincible. Despite putting what looks like a lot of money into its production, Netflix seems to have put very little effort into its marketing. Very few mainstream critics bothered to review it. Even so, it has all the elements of a word-of-mouth underground hit, and it is therefore hard to understand why its viewer ratings remain mediocre. While it may be that the figures were reduced by disgruntled fans of the comic books, one might have thought it would find its own niche market at the more family-friendly end of the spectrum. It is, after all, a great children's show in which even parents might find something to enjoy.

Perhaps the mistake was pitching it too much in the middle. Usagi is sixteen, an age when youngsters tend not to watch cartoons because they are self-conscious about not wanting to be seen to be childish. To paraphrase C S Lewis, at fifty, one is no longer embarrassed to admit one enjoys watching children's animation one would not want to admit one enjoyed at fifteen. This fiftysomething enjoyed Samurai Rabbit thoroughly but is hardly its target market. Indeed, it does not seem to have a target market. This is a pity because it is one of the best recent productions I have seen in the last few years, much better made in fact than the hugely expensive feature films of the Marvel and Godzilla franchises it satirises. That hundreds of millions are lavished on such films while this classy animation languishes on the Netflix surplus content pile, is further condemnation of the current state of the entertainment industry.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 11th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.