Shelley

1979 - United KingdomReview: Brian Slade

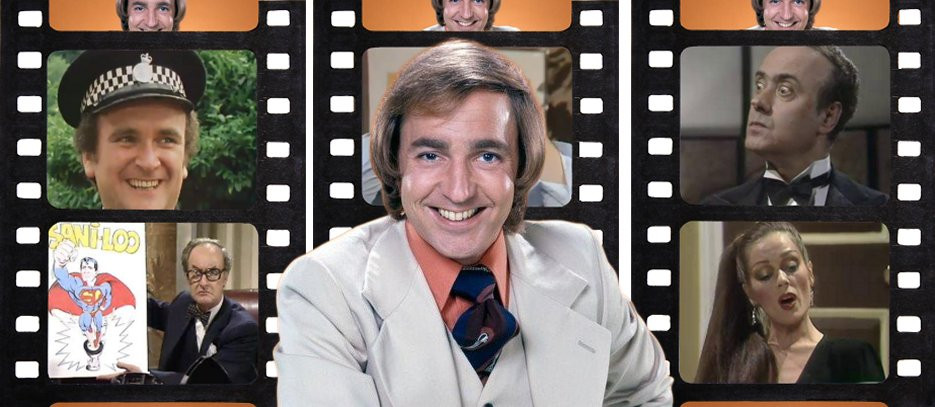

In 1979, Thames Television introduced us to James Shelley. Shelley would, with a brief hiatus in the middle of the 1980s, remain a popular show and indeed character through to 1992, running largely in parallel with the Margaret Thatcher era, and indeed outlasting her. Peter Tilbury’s creation was undoubtedly the career-defining role for Welshman Hywel Bennett, and despite his sarcastic and slovenly approach to the world, Shelley had a charm that pulled in as many as 18 million viewers at the show’s peak.

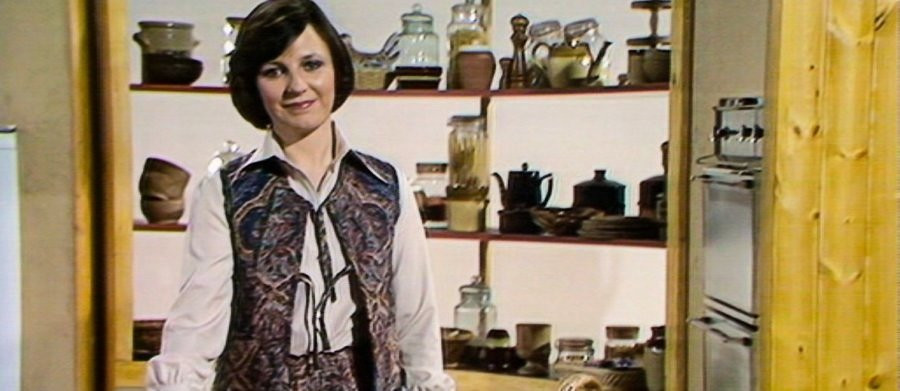

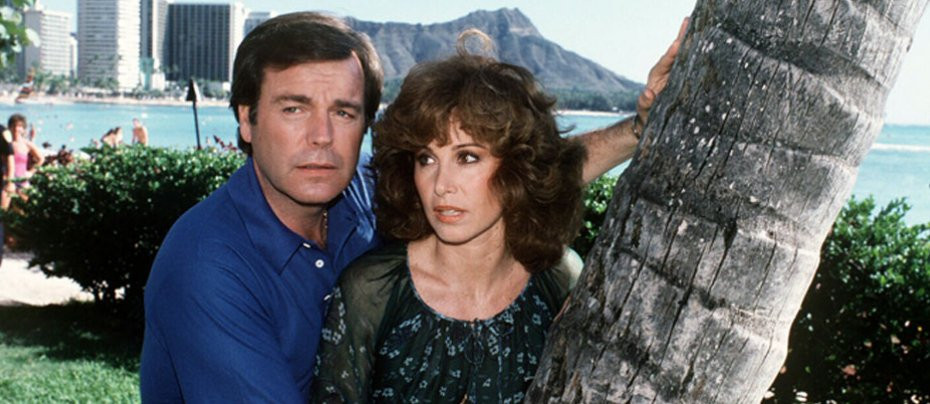

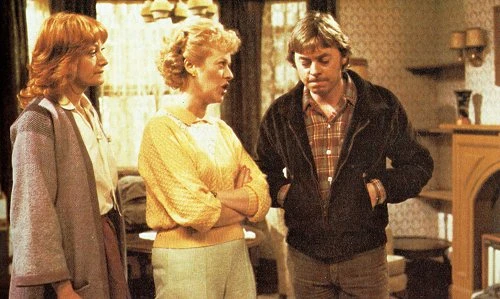

Shelley is 28 years old when we first meet him. Looking through the apartments for rent section of the local newspaper in the local café, he’s happily hitting on the waitress while at the same table as his long-suffering girlfriend Fran (Belinda Sinclair), who really doesn’t care or rate his chances. Shelley is unemployed, as he pretty much is for the entire duration of the show’s ten series. It’s not that he isn’t qualified – he has a degree in geography and indeed a PhD – but he simply can’t be bothered. Even in the final few series, while his morals have remained firm in some ways, he still cannot bring himself to face full-time employment, merely promoting himself as Chief Executive of Global Slobs plc.

Shelley charms his way through lies and deceit to get what he wants. In the early series, he has already bamboozled landlady Edna Hawkins (Josephine Tewson) into letting him and Fran rent a one-room bedsit, and it is his intelligent use of words that continually allow him to stumble through life without falling foul of the authorities. His stint at the job centre is already on week 69 when we meet him, and he swiftly points out to the bewildered staff that ‘It’s us hardcore layabouts that are your bread and butter,’ suggesting that long-term job absenteeism keeps the job centre staff themselves from becoming unemployed.

Shelley initially lasted for six full series through to 1984. During that time, Fran became pregnant and gave birth to a baby girl, but it did nothing to alter Shelley’s laid back approach to responsibility. By the time we bid farewell to Shelley, Fran has tired of his cynical laziness, and she leaves him for a new life with their daughter and jets off to Canada. By now, Shelley’s powers with women have worn badly and he finds himself in a different dating world to the one he previously knew, being described by his new landlord’s niece as ‘a good old-fashioned would-be hubby with a non-conformist streak nine miles wide.’

After several years away, Shelley returned to our screens in 1988 under the title The Return of Shelley. The absence is explained as Shelley having been travelling the Middle East, teaching English to students. He is referred by a local accommodation agency to a couple who are renting out a spare room, as true to form Shelley has returned from his travels with limited funds or prospects. By now, Thatcher’s perceived yuppie era was in full flow, and that world faces the full lampooning treatment from Shelley. Looking to pay £40 per week, he is forced to pay nearly three times as much to rent from Graham and Carol, a young couple whose goals in life are purely financially driven. They plan to let Shelley rent the room entirely based on the understanding that he will be evicted as soon as they can make an obscene profit on it, all fitting in with their plans to be millionaires by the time they turn 35. Their focus is so much on material gain that the couple admit to having no time for jokes, hence why they initially evict Shelley two and a half hours into his tenancy, having referred to their fiscal focus as making them nothing more than muck spreaders.

The changing times that the 1980s were are reflected throughout the next two series. Old friends have become impossible to make contact with due to busy lifestyles and the yuppie people in Shelley’s new life are not spared his sardonic disapproval. He suggests the next great money-making plan will be selling British grandmothers and turning Wales into a sceptic tank. His new acquaintances don’t get him, and he doesn’t get them. He sees Carol as a human version of Mrs Thatcher, and bemoans the demise of the rebellious oiks, as he recalls his younger days.

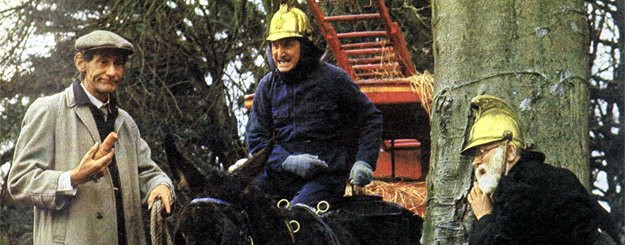

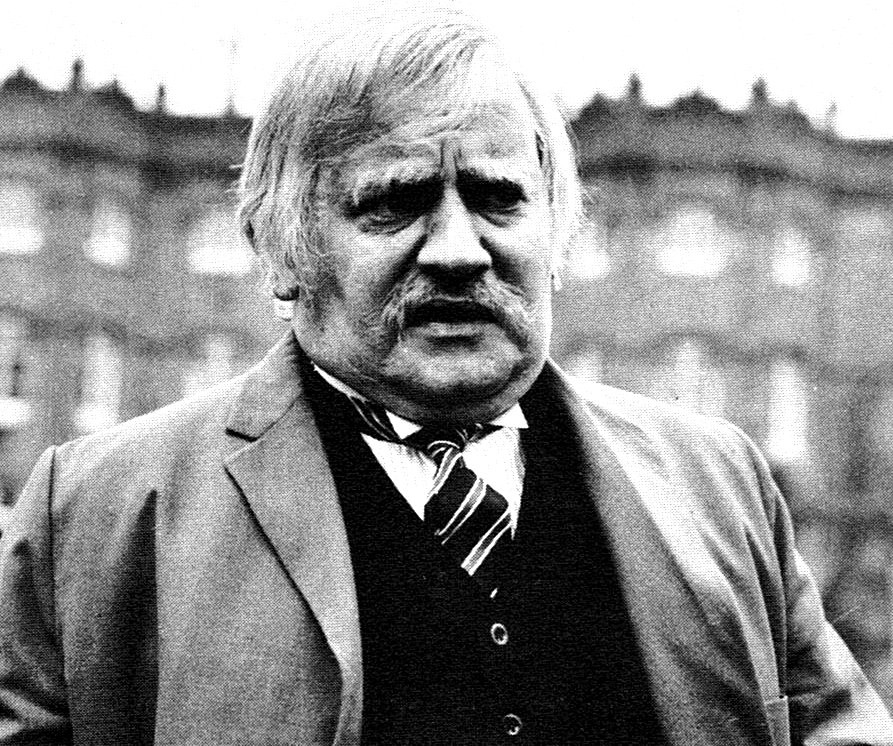

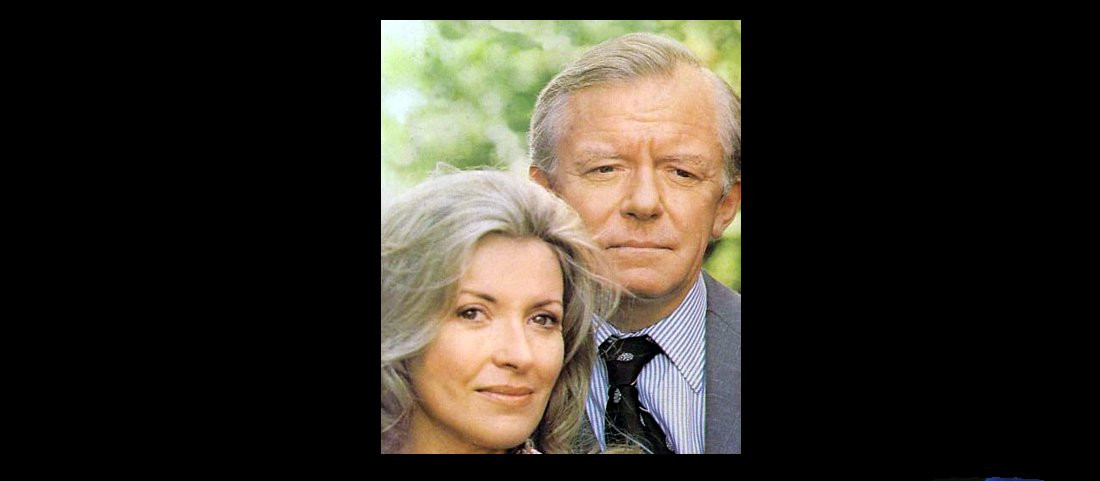

After two series suffering under the money-making eye of people he shared little in common with, Shelley was on the move once again. This time he set up lodgings with Ted Bishop, renting one room in Bishop’s seemingly doomed home, ironically for £40 per week. The reason for the low rent would appear to be the impending demise of the building. As the sole remaining house in its street, Bishop’s time is spent thwarting plans for demolition to make way for Streatham’s new hypermarket and leisure centre. Shelley, upon seeing the bullying tactics of suited representatives of the developers, decides to take the room and join forces with Bishop, still rebelling against Thatcher’s Britain. To the end, Shelley remains unchanged. When Bishop explains about his desire to remain in his lifelong home rather than accept the developer’s pay-off, he asks Shelley if he’s ever known a building that he’d spent so much time in that it became part of him, to which he drily replies, ‘Yes – the job centre.’

Shelley never finds another romantic interest to settle down with. Fran remains involved in the story from afar. By the time of The Return of Shelley – the ‘The Return of’ element of the rename was dropped after one series – Fran is still referenced and we do meet his daughter again in later years, and indeed Shelley is communicating with Fran into a Dictaphone. It’s one of the devices the writers use to maintain an element of fourth-wall manoeuvrability. In the early series, Shelley has plenty of characters around him to spout his wisdom to, but as the regular characters drop out, the programme develops a Tony Hancock feel. Shelley doesn’t specifically talk to the camera, but comes very close as he spends a good deal of his time talking in solitude, and in later years we even have an internal monologue voiceover during conversations Shelley is tiring of.

Tilbury played a very delicate game in creating Shelley. Writing about a character who simply didn’t want to go to work needed a strong hand to keep people on his side, otherwise the character would have been too difficult to warm to. But warm to him we did. He is dry, cynical and sarcastic, but Tilbury, and those writers that followed him, balanced that expertly with intelligent use of the changing political climate, the character’s undoubted intelligence and just that bit of cheeky charm, evident from episode one when he frequently implores people to, ‘call me James…nobody does.’ Indeed they did not. Hywel Bennett had other subsequent successful roles in well-known programmes like EastEnders and The Bill, but in the world of television comedy he will be affectionately remembered by just one word – Shelley.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 4th, 2020. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.