Terminator: the Sarah Connor Chronicles

2008 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

One of the positive side effects of Game of Thrones is that it finally gave a number of actors who had done a lot of good work over the years the international recognition they deserved. Top of that list is Lena Headey, who made Cersei Lannister possibly the most consistently compelling character - at least until the writers seemed to lose interest in her in the last season - but who was already well respected as someone on whom a director could rely to put in a quality performance. She had therefore been in fairly constant employment for two decades, making a mark even in supporting roles in prestigious projects like 'Ripley's Game' and '300.'

In 2008 she was rewarded with the leading role in a television series, Terminator: the Sarah Connor Chronicles. She made good use of the opportunity, and, although it did not last long, it provided the best showcase for her talents prior to Cersei.

The show was a television "spin off" from the hugely successful 'Terminator' film franchise. Such projects do not, as a general rule, enjoy a good reputation and tend not to last very long. 'Terminator: the Sarah Connor Chronicles' was superior of its type, thanks in no small part to Headey, and deserved to last longer than it did.

Although the series was made several years after the third film in the original trilogy, the producers made the sensible decision to set it soon after the more successful second film and ignore the new "time line" established by the third altogether.

These different "timelines" are necessary plot devices because, as any half decent cosmologist will tell you, time travel is physically impossible. Apart from anything else, there are simply too many potential paradoxes, the biggest being that if you travel back from the future to change the past, then the future is no longer the future. The notion of alternate "timelines" is therefore a legal fiction introduced into science fiction long before 'Terminator' in order to make time travel stories work. More often than not, they fail, not least because multiple "timelines" tend to get tangled. The original 'Terminator' trilogy was an infamous case in point even before the television series, which tangled them up some more, as did three subsequent films. One ends up agreeing with Basil Exposition in 'Austin Powers': best not worry about these things really.

Headey took on the part of the eponymous Sarah Connor, played by Linda Hamilton in the films. This upset some fans who basically wanted 1991 Linda Hamilton, ignoring the fact that even Linda Hamilton was not 1991 Linda Hamilton in 2008.

Sarah Connor is a significant figure in the history of women in action adventure film. She developed from a traditional "damsel in distress" in the first half of the first 'Terminator' into a tough warrior in the second. There was something of a fashion for warrior women in cinema around the time of the original film - Sigourney Weaver as Ripley in 'Alien,' Sandahl Bergman as Valeria in 'Conan the Barbarian,' and the late Lana Clarkson as Kaira in 'Deathstalker,' among others - and it took television several years to catch up with Xena Warrior Princess and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Hamilton differs in that we actually see her character evolve.

Headey offers us a credible continuation of that evolution. Although her physical resemblance to Hamilton is not strong, she is visibly the same character. Yet Sarah has matured. Her experience in a mental hospital and her interaction with a "good" Terminator in the second film has evidently taught her caution. She has calmed down a little. She has learned that situations tend to be more complicated than they appear. One cannot imagine Headey's Sarah rushing off impetuously to try to murder an innocent man as Hamilton's did.

The story picks up in 1999, four years after the events in the second film, but is almost immediately, through a clumsy use of the time travel plot device, transferred to 2007. The producers obviously did not want to waste time and money making sure that viewers were not distracted by seeing 2007 cars, computers, and whatever else might be slightly different, in what was supposed to be 1999.

The point is that Sarah and her son are emotionally and biologically four years older, not twelve. As the story opens, Sarah is still in an advanced state of paranoia - quite understandably - even if she has relaxed a little in the belief that she saved the future in the second film. This is a mistake, because one of the themes of the franchise is Destiny - and how it tends to find a way. Although the actual technology that led directly to the Terminators was destroyed, technological advances are still happening all around, and when they get to 2007 Sarah and John find that the process has accelerated. They cannot hold back a technological revolution on their own.

Anyway, those pesky Terminators are back somehow, and still obsessed with their failed strategy of trying to kill John Connor, the leader of the forces which destroy them in the future. Sarah is therefore back to doing what Sarah does best. Her maternal instinct goes into overdrive. However, the future leader is now four years older, four years closer to the man he is to become. If his childish rebellious streak is gone, it has been replaced by the normal healthy desire to assert his independence of the ultimate overprotective mother. This sets up an interesting psychological relationship and some conflict between the two.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note how many of the great leaders of history - including Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Napoleon - lost their fathers at a young age and were somewhat dominated by very strong mothers. We see the same happening to John Connor, but he is beginning to resist - just as he will later resist the Terminators. Sarah's final contribution to her son's development as the leader she wants him to be is therefore involuntary. Yet she has learned to avoid direct confrontation. She tries more subtle forms of control, but that leaves a dangerous lack of communication between mother and son when they are supposed to be fighting for their lives together.

It also impacts emotionally when Sarah struggles alone with a serious health issue which those who saw the third film might remember. Beneath the formidable warrior mother is still a vulnerable woman. Headey balances the two with great skill.

Good as she is, it was perhaps inevitable in a Terminator project that Headey's nuanced performance as the leading human was upstaged by what is always the showy role in the franchise, that of the leading Terminator. For this the producers went as far from Arnold Schwarzenegger as it is possible to get, selecting the fragile looking Summer Glau as Cameron, the "good" Terminator sent back in time to protect John.

Glau has the wonderful face of a pretty China doll, which is a great asset when she assumes the blank doll-like expression of a robot imitating a human, which is most of the time. She has a wonderful deadpan look and intonation which, oddly like Schwarzenegger, she deploys to great comic effect. Even better, however, are her attempts to appear more realistically human so that she might better blend in order to fulfil her mission. We see an artificial intelligence experimenting with new data as she tries to copy what she has seen. As she proved in Firefly, Glau excels as a character observing humanity from just outside. It is often hilarious, and sometimes poignant, but whenever we get too comfortable with her, we are reminded exactly what she is, literally a remorseless killing machine.

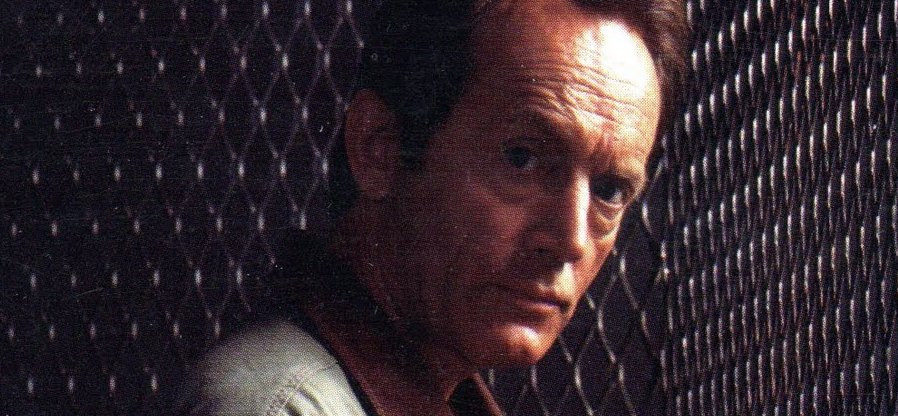

These outstanding performances by Headey and Glau rather overshadow the male side of the cast. While Thomas Dekker and Brian Austin Green are both good as, respectively, the young John Connor and his uncle from the future, Derek Reese, it is the women who are more memorable. Garret Dillahunt is perfectly cast as the principal "bad" Terminator, while Richard T Jones is very effective in a potentially difficult role as a tenacious FBI Agent whose religious faith opens his mind to possibilities others discount.

Engaging as they do with issues such as faith and free will, the scripts are intelligent and literate. Some of the set pieces are positively cinematic. One in the first season finale was particularly powerful - when you start to hear Johnny Cash singing "When The Man Comes Around" you know something big is about to go down, and it might be a good idea to make yourself scarce if you happen to be a supporting or unnamed character.

The big weakness of the show was its overreliance on time travel as a plot device. In the original film trilogy, the whole point was that it was something extraordinary, but the television series turns it into something of a commuter run with 2007 as Grand Central Station or King's Cross.

This became more of a problem in the second season. The first season was a tight nine episodes due to it coming in mid-season. Its success led to an order for a full 22-episode network season. That was probably too much. The plot became very busy with even greater reliance on characters having travelled back from the future. It became hard for viewers to keep track and stick with it. Many did not, and ratings declined, even if they remained respectable. Meanwhile the franchise itself was more concerned with the upcoming feature film 'Terminator Salvation,' and the way the television series was complicating the "timelines" even more was not helpful. Even so, many were surprised by the cancellation: the final episode was a "cliffhanger" that looked set to take the show in a different direction. One cannot help thinking what might have been - especially if it had been made, like so many shows today, in seasons of ten episodes. It was certainly a lot better than the two films that followed.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 17th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.