The History of ITV - The Independent Applicants

"Performers unions will not agree with the BBC over terms for film recording."

Although the November '53 Government White Paper directed no criticism directly at the BBC the Corporation was certainly not without its critics. Writing in The Television Annual for 1955 respected TV critic Kenneth Baily wrote: "In its attitude to the public the BBC is an odd mixture of scholl-marm and slavey. With superior haughtiness it considers that the policies at the heart of its services must never be ventilated. It feels so self-sufficient that it sees no reason why it should share its problems with the people paying for its keep."

Bemoaning the lack of variety on the nation's TV screens Baily noted "The quiz which scored high (in viewing figures) is kept on ad nauseum, with the same personalities; and then it is copied ad nauseum by other quizzes under different titles. The variety pattern which scored high is repeated again and again; and then with different artists when the first ones tire." However, one of the problems for the lack of variety lay in the fact that there was no variety. "Television cannot go to the Palladium because theatre managements and performer unions fear that even the occasional televising of live theatre shows will lessen audiences at the theatres. Performers unions will not agree with the BBC over terms for film recording."

Baily saw the inability of the two mediums to meet on common ground more the fault of the BBC than an obstructive stance taken up by the unions. "The public, which has been inconvenienced by the deadlock for several years, has never been given the full facts from which it could judge for itself whether the BBC terms are inequitable, or whether the unions' objections are nothing more than obstructionist policy born of fear." He wrote. "If the latter is the case, why does the BBC refuse to rally public good-will to its side by stating the terms it's offering? By telling us exactly what terms it's offering to the entertainment unions and sports promoters for rights essential to TV's progress, the BBC could rally public goodwill to its side. Lacking this, we are inevitably inclined towards the assumption that its terms are shabby ones, rightly scorned by the unions and promoters. In that event the BBC cannot escape the indictment that it values the proper development of TV too little, and the convenience of its paying public hardly at all."

If television was in fact giving its public such a poor deal in the entertainment stakes then why was it developing at such a fast pace? Baily again: "It seems likely that large numbers of people in Britain today are letting cinemas, theatre and sport events go by default simply because the TV is on and something good may turn up for them. This does not mean that they prefer TV, or are even actively choosing it instead of other pursuits. It is simply more convenient for them to sit around and wait while the bran-tub of Lime Grove (the studios where BBC programmes were made) disgorges itself. At present, ease and convenience are the real power of TV." However, all was not doom and gloom in Baily's opinion and the coming of independent television could only benefit the Corporation. "Where the BBC rule of TV is muddled and weak there will assuredly rise a fever of new thinking. This, we can but hope, will be to the BBC viewer's benefit, whatever alternative attractions lure his eyes."

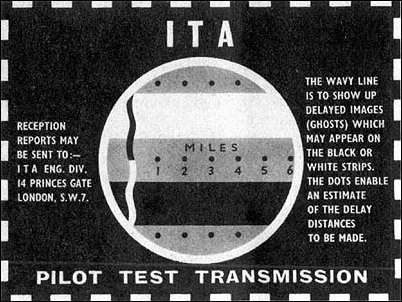

Having passed the Television Act the next step the Government took was to appoint a commission under the leadership of Sir Robert Fraser Brown, a 51-year old ex-journalist and politician. That commission was to be known as the Independent Television Authority or ITA. Sir Robert's second in command was Sir Kenneth Clark and below him was a Government appointed Board of Directors who would eventually grant franchises to successful applicants for broadcasting commercial television to the different regions of the country. For this, advertisements offering applications were placed in The Times newspaper on 25 August 1954 -which read:

THE INDEPENDENT TELEVISION AUTHORITY INVITES APPLICATIONS FROM THOSE INTERESTED IN BECOMING PROGRAMME CONTRACTORS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PROVISIONS OF THE TELEVISION ACT. APPLICANTS SHOULD GIVE A BROAD PICTURE OF THE TYPE OF PROGRAMME THEY WOULD PROVIDE, THEIR PROPOSALS FOR NETWORK OR LOCAL BROADCASTING OF THEIR PROGRAMMES, SOME INDICATION OF THEIR FINANCIAL RESOURCES AND THE LENGTH OF CONTRACT THEY WOULD DESIRE.

The Government had already given the ITA a strict set of guidelines which insisted that 'programmes are of high quality; that a proper proportion of films and telefilms are British;' and that 'the amount of advertising shall not be so great as to detract from the value of the programmes'. To be more specific, the Authority had the right to call for schedules and scripts in advance, to ask contractors for recordings if it wanted to examine a particular programme, to forbid broadcasts on certain subjects and to regulate advertisements. It was envisioned that the appointed companies would be, by and large, self-regulating with the ITA holding their powers in reserve.

No advertisement would be allowed "which will lead children to believe that if they did not own a certain product they will be inferior to other children."

As far as advertising was concerned the ITA stipulated that only ten per cent of programme time (six minutes in every hour) could be taken up by advertising and that this would have to come in what it described as 'natural breaks', i.e. the beginning and end of a programme or during an 'interval'. Nothing would be allowed to interrupt the smooth running of a programme. For the privilege of showing viewers their products advertisers were expected to pay between £87.00 (for a quarter of a minute during a test time) and £1,000 (for a full minute at a peak viewing time). The ITA also insisted that there should be no connection between the actual programme and the advertisements, except in shopping guides. The ITA also stated that no advertisement would be allowed, "which will lead children to believe that if they did not own a certain product they will be inferior to other children."

With the guidelines for broadcasting and advertising set the Authority soon found that they had to amend the rules for the all-important franchise applications. Although Parliament had voted a grant of £750,000 to the Postmaster-General to set ITA on its feet and also made provisions for loans up to £2,000,000 over five years for equipment, the Authority soon found itself having to demand that any applicant wishing to be considered for a franchise be in a position to back itself up with an initial capital investment of £3million. This ruling was in response to an opening number of 98 applications. With these new rules many of the applicants withdrew until there were just 28 interested parties, and of these only six were considered to be sufficiently experienced and suitably backed to take on the responsibility of bringing in the new age of commercial television.

Amongst those that stayed the course was the Associated Development Broadcasting Company (ABDC), headed by Norman Collins and backed by Sir Robert Renwick and Charles Orr Stanley. Another contender was Associated Rediffusion, a company formed by Broadcast Relay Services and Associated Newspapers. The Controller of Programmes for this company was a 46-year old Englishman by the name of Roland Gillett who had learned all about the television business in the USA. "My aim," he said, "is to use the best ideas in American competitive TV, and leave out the worst. British commercial TV will have to grow up quickly, but we have up our sleeve some revolutionary methods which may even put us jumps ahead of the United States."

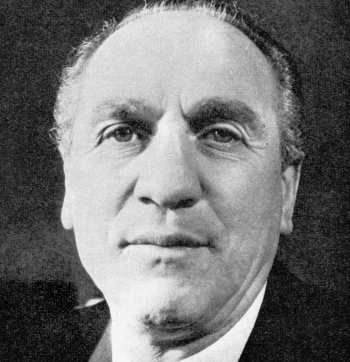

Granada Television was a subsidiary of Granada Theatres, a group controlled by Sidney Bernstein and created by him and his brother Cecil. Its application was to operate in the north of England. Although the other competitors seemed prepared to unite against the competition of the BBC, Sidney Bernstein preferred to play a lone hand. "We are treating everyone as competitors," he said, "and that includes the other contractors. Wherever interest and demand exist we shall meet them, but we do not intend to pander to the lowest level of taste." The fourth company was the Kemsley-Winnick group, which combined financing by Lord Kemsley's newspaper empire and the experience of Maurice Winnick, an impresario who had already brought the hit US game show What's My Line? to the BBC.

The fifth company was the Associated British Picture Corporation.

The sixth company was The Incorporated Television Company (ITC).

At this time one of the top booking-agents in the country was Lew Grade. Grade had a reputation for having an eye for talent and an instinct for knowing what the public enjoyed. He was also a superb salesman and raconteur, enjoying a good relationship with a growing number of showbiz personalities. One of the acts that Grade often found bookings for was million-selling recording artist Jo Stafford, and one day, in 1954, her manager Mike Nidorf phoned him up from the offices of Suzanne Warner, who acted as a publicity agent. Nidorf alerted Grade to the advertisement in The Times inviting the franchise applications, but Grade had already heard about the £3 million investment required. In response to Nidorf, Grade told him that he simply couldn't raise the capital to make the application, at which point Nidorf told him that, "provided you have a sufficiently distinguished board to make the application, plus £1 million; Suzanne has someone who is prepared to put up the other £2 million."

Grade demanded to speak to Suzanne and when she came on the line he asked her who was prepared to put up the other £2 million. Suzanne told Grade that she was sworn to secrecy, and he hung up on her. She rang back almost immediately to tell him that the backers were the Warburgs. Not being a follower of the City financial pages, Grade had no knowledge of the Warburgs at all, so he phoned up Sid Hymans, who, together with his brother Phil, owned four of the biggest cinemas in London. "Sid," he asked "are the Warburgs good for £2 million?" Sid Hymans told him, "Lew, they're good for £50 million!"

"You're in the television business!"

Without further hesitation, Grade said, "Sid, you're in the television business!" He then made a flurry of phone calls. In order to raise the £1 million and also put together the board that he wanted, Grade phoned Val Parnell, the Managing Director of the Stoll Moss Theatre Group, then Stuart Cruickshank of Howard Wyndham Theatres, Binkie Beaumont, head of H. M. Tennants, the most important producers of plays in London, and Dick Harmel who was the right hand to South African millionaire businessman John Schlesinger. Each person that Grade phoned he told that he would let them know in due course how much he wanted them to invest, then he phoned back Suzanne Warner and set up a meeting with the Warburgs. The whole thing had taken about an hour.

There was still one more hurdle to overcome. Val Parnell phoned Grade back to tell him that his boss, Prince Littler, who was the owner of Stoll Moss, was totally opposed to television and as such would not allow Parnell to become involved in any consortium. Grade immediately went round to see Littler, and in two hours had not only convinced him that rather than try and stop progress and be overtaken by it, he instead should become a part of it and become a partner. He came away from the meeting with Prince Littler's agreement and financial backing, as well as a major coup. What the BBC had failed to achieve in years of negotiation Grade had succeeded in a few short hours. Television and the variety theatre were about to become bedfellows.

Grade then met with the Warburgs who appointed Commander James Drummondas their nominee to the board. They had £500,000 in the bank, the money from the Warburgs, plus the promised investments from all the others that Grade had phoned. They called themselves the Independent Television Corporation (ITC). With Suzanne Warner appointed as their press officer they made their application, outlined their plans for the new station and set into motion a huge publicity campaign. By that time Lew Grade's company had merged with London Artists who represented the biggest names in the 'legitimate' theatre such as Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, amongst others. It was such an impressive line-up that they must have been confident of winning the franchise. It was because it was such an impressive line-up that they didn't.

Research: Laurence Marcus October 2005. Reference Sources: TV Mirror Annual, The Television Barons (1980), Wikipedia, The Guinness Book of TV Facts and Feats, The Television Annual (various editions), Still Dancing by Lew Grade, Ian Freeman (in conversation).

Previous Chapter: The Battle for Independent Television Next Chapter: The First Franchises, Launch and Near Disaster

This article was first published on Television Heaven's companion site Teletronic. A much fuller account of ITV's early days as well as a comprehensive history of television can be found here.

Published on April 25th, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.