The History of ITV - The Pilkington Report

It was Roy Herbert Thomson - Lord Thomson of Fleet, who first dubbed the formula for commercial television as 'a licence to print money' when he launched a successful bid for the commercial television franchise for Central Scotland (later named Scottish Television) in 1957. The quote must have rankled the hard-core anti-ITV faction, of which there were many. But it also upset the men who ran the independent channels. They vehemently denied the claim as untrue and indeed in the early days it may well have been, but it was not a state of affairs that would last for long and soon---the golden goose that was commercial television began to lay its golden eggs. (1)

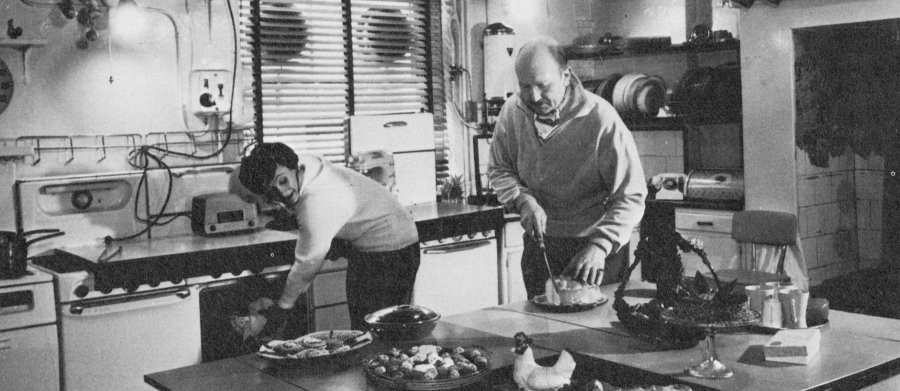

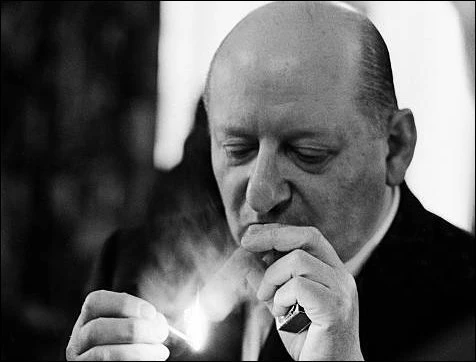

In March 1956, just 6 months after its launch ATV had run out of money. The 1954 Television Act had made provision for loss making television in the early days setting up a contingency fund of £750,000 to help finance production. But the Treasury wrapped the application for assistance in so much red tape that not one single penny of it was ever made available to the company. Kenneth Clark, second in command at the Independent Television Authority, ITV's governing body, tendered his resignation over the fiasco. In order to stay afloat shares in ATV were sold to the Daily Mirror Group and other shareholders had to raise money of their own. Lew Grade claimed he was forced into selling his wife's jewellery in order to raise capital. But the crisis was a short-lived one. ATV was the first independent broadcaster and it was some months before the Midlands and eventually Lancashire came on the scene and advertising revenues began to pick up. In his autobiography Grade wrote that 'June (1956) was the turning point. Large sums of money were being made by all four of the major companies.'

In programming terms, the arrival of ITV breathed new life into television in Britain. ITV liked to be known as 'the people's channel' claiming to do something that the BBC had thus far failed to do; give the people the type of programming they wanted. But it was quickly criticised in many quarters for its mainly populist fare. Regardless of the fact that by 1957 ITV dominated Britain's homes with an 80% share of the potential audience, variety specials such as Sunday Night at the London Palladium, quiz shows such as Double Your Money and Take Your Pick, innovative shows such as Armchair Theatre, action-adventure series' like The Adventures of Robin Hood and in particular American imports such as I Love Lucy were being held up as examples of everything that was wrong with commercial television.

So, the question remains; was it really the quality of the programming that ITV's critics found so abhorrent? And if not, what was it? One of reasons could have been the vast profit they were making. ITV had done everything in its power to supply the balanced diet that the ITA had demanded. Current affairs were catered for by Granada Television who were surpassing anything in quality and in-depth reporting that the BBC had to offer. Children's television was offered in the form of exciting swashbuckling series' but also in the forms of gentler entertainment such as Rolf Harris' art show, while the demur Muriel Young read stories to youngsters-and these were presented in far less stuffy style than the BBC was offering at that time. ITV were the first broadcaster to air an hour of religious programming on a Sunday and even persevered to bring Christianity to a younger audience with its show The Sunday Break.

But it seems that ITV was expected to bring these shows to an audience without making a profit, or in the very least, without making a profit that it's critics obviously deemed as obscene. One of ITV's biggest critics was Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express newspaper. In the 1950s the paper, following his sour grapes policy on commercial television, printed a rather unflattering picture of Lew Grade with a caption that read 'Is this the man you want to choose the programmes for your children?' Well, as far as the audience was concerned the answer was a resounding yes.

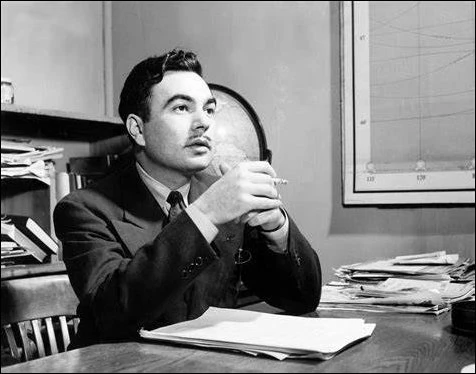

Audiences didn't want the type of stilted, uninspiring and sanitised programming the BBC was then showing even though ITV made several attempts to offer it to them. When ITV presented its viewers with Hamlet viewers turned off in droves with viewing figures dropping below 10 per cent. Sydney Newman, the Canadian born producer who helped shape the 'kitchen sink' drama of Armchair Theatre in the UK summed it up perfectly when he said, "at the time, I found this country to be somewhat class-ridden. The only legitimate theatre was of the 'anyone for tennis' variety, which, on the whole, presented a condescending view of working-class people. Television dramas were usually adaptations of stage plays, and invariably about upper classes. I said 'Damn the upper-classes -they don't even own televisions!' My approach was to cater for the people who were buying low cost things like soap every day. The ordinary blokes the advertisers were aiming at." The results spoke for themselves. Under the helm of Newman, the weekly dramas reached the top ten ratings for 32 out of 37 weeks between 1959 and 1960, with audiences of 12 million viewers." It would appear that ITV's biggest crime was in being too popular. This upset the establishment and the knives were drawn.

In 1960 a committee was set up under Sir Harry Pilkington to investigate the broadcasting industry and allocate a third television channel. During its deliberations, the Treasury introduced a flat levy of 11 per cent on all income from advertising. It would be two years before the committee delivered its findings. Pilkington's own team was a mixed bag indeed and included the actress Joyce Grenfell, footballer Billy Wright, Dr Elwyn Davies (who would be appointed Permanent Secretary of the Welsh Department of the Ministry of Education in 1963), theatre director Peter Hall, Sir Jock Campbell and J Megaw (the last three all resigned between January and February 1961). Sociologist Richard Hoggart was also a prominent member of the group and was the person responsible for drafting the report. As well as their own thoughts the committee heard evidence from broadcasters, advertisers, public bodies, schoolteachers, local women's institutes, rotary clubs, advisory councils and any other crank that wanted to give an opinion. What they came up with was a thoroughly scurrilous report that smacked of nothing less than arrogant stuffiness, bias and snobbery.

Much that is seen on television is regarded as of very little value. There was, we were told, a preoccupation in many programmes with the superficial, the cheaply sensational. Many mass appeal programmes were vapid and puerile, their content often derivative, repetitious and lacking any real substance. There was a vast amount of unworthy material, and to transmit it was to misuse intricate machinery and equipment, skill, ingenuity and time.

'The BBC know good broadcasting; by and large, they are providing it.'

'We conclude that dissatisfaction with television can be largely ascribed to the independent television service.'

-The Pilkington Report.

If we accept that Independent Television was not providing quality programming all the time, and it would be difficult to put forward and argument that it was, even though it was nowhere near as bad as Pilkington claimed-could there be another reason for the committee's condemnation? Other than the previously suggested financial one?

Writing in the 1959 Television Annual (a year before Pilkington was commissioned), Kenneth Baily considered the political aspects of a proposed third channel and advertising on the BBC:

'Some observers suggest BBC Television can only be saved from becoming a poor second in the field by admitting a limited amount of commercial television to its service. As the advertisers are asking for more TV space, this might offer a neat way out. The Government could award the extra channel to the BBC, along with legislation permitting some advertising on BBC.

But it seems likely that such a decision would depend on the Government's feeling over the political power of television. In short-how especially valuable is a strictly uncommercialized BBC to the Government? However admirable the BBC shows independence in its programmes, it has become part of the Establishment. At any time of political crisis, it can be relied upon to take the official line by whatever Government is in power. It was constituted thus, and it now works this way almost automatically, a kind of alarm clock geared to No. 10, Downing Street.

It would appear that the introduction of a small amount of advertising into BBC television programmes need not change this. But it might be the thin end of the wedge, to be followed by ever-increasing commercialisation. The question then arises whether a commercial television organization could be trusted by the Government to follow its line in a crisis as certainly as it can the BBC.

...a political situation might arise in which the influence of commercial interests on ITV broadcasting might be a danger to some future Government. At such a moment of crisis it would need only one partisan news or discussion programme, hurriedly put on, for damage to the Government to be done, before the ITA could close down the rebels! Such a happening may seem very un-British. But this does not make it any less worrying to wary politicians!

...To politicians this is no extreme kind of reasoning. They are now so conscious, and therefore wary, of the power of television that they will be meticulous in deciding future legislation affecting the organisation of TV services.'

So, is there enough evidence here to suggest that the Pilkington report was a put-up job by the Government in order to clip the wings of ITV and put them firmly in their place? Consider; years later, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's reaction to Thames Television's controversial documentary "Death on The Rock", part of the current affairs strand This Week. The programme questioned the authority of British troops who had gunned down a group of suspected Provisional IRA terrorists who were allegedly planning an attack on the British military on Gibraltar. The documentary was regarded almost as an act of treason by many Conservative politicians, and most certainly by the Prime Minister herself who responded by presiding over the creation of the 1990 Broadcasting Act.

The aim of the Act was to reform the entire structure of British broadcasting, described by Thatcher as "the last bastion of restrictive practices". It resulted in the abolition of the Independent Broadcasting Authority, which was replaced with the Independent Television Commission and Radio Authority, which were given the remit of regulating with a "lighter touch". Many saw this as a "dumbing down" of British television. But what it also did was allow significant changes to the way franchises were won. This resulted in Thames Television losing their franchise entirely. It would appear that Kenneth Baily's prophecy that Governments would decide future legislation affecting TV services as a direct result of a controversial issue had become a reality, and Thames paid the ultimate price.

But in 1960 the British Government just might have used their self-appointed watchdogs to head off any idea ITV may have had of not towing the party line. It had been widely assumed since 1954 that the third British television channel would be an independent one. But following Pilkington's recommendations it was given to the BBC. There were other changes that affected ITV, as well. Even so, these changes didn't go as far as the report recommended. Had they, it probably would have ended ITV as we came to know it. The report suggested that the ITA should take scheduling away from the TV channels and commission programmes themselves from independent producers. The ITA would then take the advertising revenue and use it to pay for productions. The full recommendations of the report were not carried out because they didn't need to be. It was enough that the threat was there. ITV saw it, and changed.

The first thing that was thrown out was Ad-Mags (see previous chapter). A quota was set for how many quiz shows and how many US imports were allowed to be broadcast in a week. The ITA could now force scheduling of news, current affairs and drama.

The individual companies' profits also came under closer scrutiny. The Treasury's flat levy of 11 per cent from advertising was now replaced by a sliding scale of charges. The first £1.5 million of Nett Advertising Revenue would be untaxed but the next six million would be taxed at 25 per cent and anything over that at 45 per cent. £17 million would be taken out of the companies leaving them with £15 million, which would still be taxable. Norman Collins called it 'a licence to lose money'.

Companies were on contracts with the ITA that had to be renewed and therefore could be challenged. The first round of these franchise renewals were due in 1964. The respective TV companies held their collective breath as 8 new applicants applied for the existing franchises. Then, in January 1964, Lord Hill of Luton, chairman of the ITA, announced that no changes would be made to the existing contractors from 1964 to 1967 when it was still expected that a second ITV channel would be launched. But in 1967, for many companies, their luck ran out. Established names like Associated-Rediffusion disappeared and new broadcast areas were created; Granada's great northern empire was carved up to establish Yorkshire TV. And in London, two new contractors were born.

Research: Laurence Marcus August 2007 Reference Sources: The Guinness Book of TV Facts and Feats, The Television Barons by Jack Tinker (1), ITV: The People's Channel by Simon Cherry, The Television Annual for 1959.

Published on June 1st, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.