The History of ITV: The New Franchises

Had any of the existing companies felt complacent about their future they should have taken heed of Lord Hill's earlier warning that 'all bets were off' on the next franchise round.

Long before 1967 it became clear that both technical and financial circumstances would preclude the introduction of a second ITV channel by the time the franchises were up for renewal. Many established companies took this as a sign that the renewal of their contracts was a mere formality. However, unlike the 'roll-over' of contracts in 1964, the 1967 review was to create dramatic changes to the structure of the ITV network.

Some changes were announced as early as 1966. London would remain split between two channels, one broadcasting Monday to Friday with a second contractor taking over at the weekend. The Midlands and the North would become seven-day contracts but Granadaland would now be split into two areas, east and west of the Pennines. There were 36 applicants for the 15 regional areas, ten alone for the new one in Yorkshire. Had any of the existing companies felt complacent about their future they should have taken heed of Lord Hill's earlier warning that 'all bets were off' on the next franchise round. Hill had previously been criticised in some quarters for failing to temper the arrogance of certain contractors especially Rediffusion and TWW, the latter of whom broadcast to Wales but insisted on retaining their headquarters in London. TWW reapplied for their contract under both their own name and that of WWN/Teledu Cymru as a tax dodge, but the ITA, hoping for an applicant that showed more of an interest in local issues (as well as local employment) were more than happy when Harlech Television led by Lord Harlech applied for the franchise - which they were then awarded.

A new company, Telefusion Yorkshire Limited, later renamed Yorkshire Television, was given the licence to broadcast in the newly created Yorkshire region. They then set about building Europe's first purpose-built colour television studios in Leeds (which was completed in 14 months). Granada, the existing weekday contractor for the North of England, was given a seven-day licence for the new North West region (they were deeply unhappy about losing the North as a whole). The Midlands were given to ATV who lost their London weekend slot in the process replacing ABC who now found themselves homeless. ABC and Rediffusion were forced to form a joint company to take the London weekday franchise previously held by Rediffusion alone, a move unpopular with Rediffusion who decided to be difficult and attempted to slow down the merger. Only the threat of giving the licence solely to ABC made it relent. The result, Thames Television, was 51% controlled by ABC.

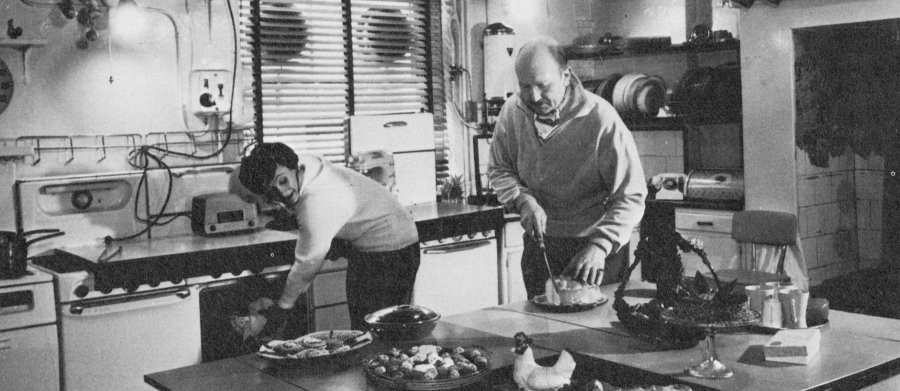

The London Television Consortium, had been put together by David Frost, the former front man of That Was The Week That Was and now an uncompromising interviewer with his own weekly TV series. The notion of applying for the London weekend franchise had apparently occurred to him at a party being held by Rediffusion. A chance remark kindled a spark in Frost's imagination and he wasted no time in going through his impressive list of contacts. Clive Irving was already working on The Frost Programme. Peter Hall, later to take over the running of the National Theatre from Sir Laurence Olivier, was next approached. Frost then recruited Head of BBC1, Michael Peacock, experienced scriptwriter, programme maker and head of BBC sitcom Frank Muir, Doreen Stephens who was head of the Corporations children's output, former ITN (News) chief Aiden Crawley and Rediffusion's very own Controller of Programmes, Cyril Bennett. For financial backing Frost went to Sir Arnold Weinstock, managing director of GEC, a company that made television hardware, and David Montagu, a merchant banker.

The only person David Frost failed to recruit at that time was the British High Commissioner to New Delhi, John Freeman. Freeman had a reputation as a fearless television interviewer and had put many guests on the spot in the BBC series Face to Face. But in spite of flying out to Delhi, Frost was unable to convince Freeman to give up his diplomatic career. Despite this, Frost's consortium tabled an impressive £6million + bid. Frost himself, as a television performer, was unable - under ITA rules - to hold a place as an executive on the board.

The Frost report that was submitted to the ITA ran 80 pages long and was clearly aimed to impress. The London Television Consortium had obviously taken meticulous note of the earlier Pilkington Report and the application was shamelessly tailored to address 'Pilkington's' every concern and criticism.

The proposed programming was exactly what the ITA was hoping for. A move up-market from populist fare such as quiz shows and sitcoms towards more solid quality arts programming and social commentary with perhaps just the merest hint of popular content. The consortium won the franchise. However, it soon transpired that what the ITA thought the public wanted and what the public actually wanted were worlds apart.

The implementation of the ITV changes led to industrial unrest in the companies. Staff employed by the different television networks were required to relocate to different parts of the country (as in the case of ATV) in order to retain their jobs, or else they would have to leave the company previously based in London and then apply for work with the new company with the London franchise. An agreement was reached whereby staff were being made redundant with a guarantee of another job to go to. The unions asked for redundancy payments for those staff relocating - which were given. But in cases where staff were being made redundant without having to relocate (i.e. when moving from Rediffusion to Thames) the unions still wanted their members to be paid the same redundancy payment. The companies refused. By the Friday after the changeover (London Weekend Television as they were now called took over the weekend schedule at 7pm on a Friday night) a wildcat strike took LWT off the air, and for most of August 1968 the regional network was replaced with an ITV Emergency National Service run by management. It wasn't until September that the dispute was resolved. But when LWT were able to offer its full scheduled service it was found severely wanting.

'No one produced a knife to cut the silence, but the silence was there to be cut and the knife was in Frost's front.'

LWT's idea of peak viewing included a Stravinsky musical drama, an avant-garde drama from Jean-Luc Godard, a tribute to Jacques Brel and Georgia Brown Sings Kurt Weil. That week and in the ones that followed there was a David Frost programme on a Friday night in which he grilled his guest on whatever touchy subject was the topic, a David Frost show on a Saturday night in which he played the consumers watchdog (in similar jokey vein to That's Life), and a celebrity talk show on Sunday night hosted by - oops, David Frost. The viewers response was to switch over to the BBC. By the end of the year the Corporation was taking up to 61 per cent of the ratings, the best it had enjoyed since ITV began broadcasting in 1955.

With Frost's audience falling away in their millions, Lew Grade launched a direct attack on London Weekend Television, singling out the 'Frost shows' in particular. It came to a head during a meeting of the Network Programme Committee. Frost was present but no one spoke out against LWT's programming policy. But Grade, who was infuriated with the way in which the audience that he had entertained so successfully for over a decade was now being poured down the sink, seized his chance: "I've succeeded in business by knowing exactly what I hate," he told them. "And I know I hate David Frost." There was silence. The other members were too embarrassed to either speak in support of Grade's blunt comment or go against it.

In his book The Television Barons Jack Tinker describes what happened next: 'No one produced a knife to cut the silence, but the silence was there to be cut and the knife was in Frost's front. Lew had once again judged the mettle of his man with complete accuracy. There was no bluster. No heated exchange. No counter-attack. And, more importantly, no defence. Eventually he (Frost) broke the awkward silence which clogged the room by saying quietly: "All right, let's talk this subject through." They did. When they were done Lew had won his reshuffle and the 'Frost' show was demoted in the schedules.1'

'Lew Grade, in theory now merely a Midland weekday franchise holder, was in practice to prove himself still the Mr Big of the Big Five. Hand in glove with the newcomers at Yorkshire, ATV dropped Frost's major Saturday night slot altogether and replaced him with Dave Allen. The other two network companies closed ranks and relegated the show to late evening. In television terms, it was like sending it to Siberia.' 1

LWT was in a mess. Their programming policy fell apart and the £6.5million they had initially put up for the franchise began to drain away quicker than their audience figures. Michael Peacock, the architect in David Frost's vision for the future of television, wanted to stick to the principles of their contract with the ITA. Controller of Programmes, Cyril Bennett, announced that LWT's first duty was to survive. Peacock resigned. The ITA stood by and did nothing. Questions were asked in Parliament. There was talk of revoking LWT's licence. In the general panic that followed the General Electric Company withdrew financial backing and sold 8 per cent of its shares to Rupert Murdoch's News of the World group. Murdoch's company then went on, unchecked, to raise their stake to a massive 36 per cent of voting shares. Murdoch was effectively in control and soon began exerting his power. When Cyril Bennett's successor, Stella Richman, reported to the board in 1971 that LWT faced 14 'insurmountable problems', Murdoch fired her. Other senior management figures were soon kicked upstairs, sideways or out of the company altogether.

Rupert Murdoch was now at the helm of a company that had no chief executive, no programme controller and no decision maker save Murdoch himself. And he had been given no authority to be there by the ITA. He had effectively bought himself in through the back door with an infusion of £500,000 in capital. Finally, the ITA reacted. The contract they had given to LWT was by now flagrantly breached. They were within their rights to revoke the licence with immediate effect. But they didn't. Instead, the ITA gave LWT six weeks to put their house in order. Assurances were required for programme policies and managerial responsibilities and it was made quite clear that the name of Rupert Murdoch was not acceptable at the top of that list. Murdoch, despite protestations of character assassination by the ITA, withdrew. He moved the main centre of his burgeoning media empire across the Atlantic, although he remained on the board of LWT.

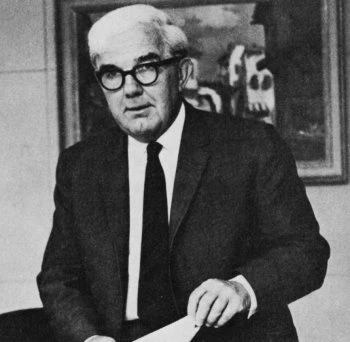

As luck would have it, John Freeman was now free to take up the post originally offered to him by David Frost. On 9 March 1971 Freeman was appointed Chairman and Chief Executive of LWT. He made one of his conditions of coming to LWT be that Rupert Murdoch stayed on. "He is a man who is near genius in financial matters." Freeman said. "And extremely experienced in the field of communications." However, it was made quite clear by Freeman the he expected to wield the power within the company without any interference from Murdoch. Murdoch readily agreed. Freeman then reappointed Cyril Bennett as Controller of Programmes. In April 1971 the Independent Television Authority announced that London Weekend was "secure in its contract."

LWT's fortunes improved in the 1970s. In 1974 Brian Tesler left Thames to become Deputy Chief Executive to John Freeman. In the autumn of 1974, LWT invested £3.75 million on what it believed represented the biggest range of talent and scheduling for viewers, which helped push up profits to nearly £4 million according to The Times newspaper.

In May 1976, LWT was reorganised, to form a new company "LWT (Holdings) Limited." John Freeman stood down as Chief Executive and the Board appointed Brian Tesler as the company's managing director. Later that year, tragically, Cyril Bennett, the company's Director of Programmes died and Tesler carried out both functions until he was able to appoint Michael Grade as Director of Programmes in February 1977. Three decades later the official history of ITV, Independent Television in Britain, observed "Under Brian Tesler's Managing Directorship LWT was to become the success for which its founders (almost all of whom had by that time left the company) had so earnestly striven."

In November 1978, News International sold off 16% of its LWT holding, reducing its shares from 39.7% to 25%, as it believed this was going to be one of the outcomes from the Annan Report on Broadcasting. LWT also warned shareholders that heavy spending on programmes would continue to reduce chances of increased profits. News International sold its remaining 25% stake on 13 March 1980, bringing an end to LWT's connection with Rupert Murdoch.

In his autobiography, It Seemed A Good Idea at The Time, Michael Grade wrote of Rupert Murdoch: "Some of his ideas were certainly original, though they betrayed a startling innocence about the realities of the television industry. Stuart Allen produced for LWT their one very successful comedy called On The Buses, which impressed Rupert so much that he sent for Stuart and proposed he increase its twelve-programme run a year to fifty-two, an idea that anyone familiar with the problem of getting even a handful of scripts out of top writers was almost risible in its naivety.

Next Chapter: Anglia Presents

Published on June 24th, 2020. Sources of research: ITV The People's Channel by Simon Cherry. The Television Barons by Jack Tinker1. Various Internet sources.