The History of ITV - The First Franchises, the Launch and Near Disaster.

At the end of the franchise bidding, ITC were left with their £500,000 in the bank but nothing to spend it on...

Following the submissions for broadcasting franchises by several companies prior to the launch of Independent Television in Britain, the ITA sent for Lew Grade, Prince Littler and Val Parnell and duly informed them that there was no way they could get a licence on the grounds that they were simply too strong and controlled too many theatres. They accused the company of having a monopoly on entertainment in Great Britain and suggested that instead of running their own television station, they should supply programmes to the companies that would eventually be given the franchises.

Sir Robert Fraser and Sir Kenneth Clark had announced the franchises. Associated Rediffusion (AR) was to have Monday to Friday in London, the Norman Collins/Sir Robert Renwick/C. O. Stanley group Saturday and Sunday in London and Monday to Friday in the Midlands. Granada was to have Lancashire and Yorkshire from Monday to Friday, whilst the Kemsley-Winnick group would broadcast to these two areas at weekends. However, Kemsley-Winnick, it seems, had greatly exaggerated their ability to raise the necessary funding and Kemsley, as well as another major backer, suddenly got cold feet. The ITA moved swiftly and told the company the deal was off whilst quickly resurrecting the previously rejected application from the Associated British Picture Corporation. The new deal with ABC was signed just one day before ITV began transmitting.

At the end of the franchise bidding, ITC were left with their £500,000 in the bank but nothing to spend it on or invest in. Then an American producer who had been living in London, Hannah Weinstein, approached Lew Grade. Weinstein wanted to make a programme called The Adventures of Robin Hood and proposed a series of 39 half hour episodes which an American TV distribution company, Official Films, were confident of selling to the United States. Richard Greene had already agreed to play the lead role and the series would cost around £10,000 per episode. Grade was so impressed by the proposal that he gave the green light for it without even consulting the rest of his board, committing £390,000 pounds of the £500,000 capital that they had at their disposal. It was a bold move by Lew Grade and certainly one that didn't meet with approval by all the members of ITC's board. However, the company now had two strokes of good luck. Firstly, the Warburgs’ stated that they were still prepared to invest the £2million that they had originally put aside for the franchise deal. Secondly, things in the Norman Collins camp were far from happy.

It was fitting that the Norman Collins consortium be offered an ITA contract. After all, it was Collins who played one of the most crucial parts in bringing the ITA into existence. However, behind the scenes things were starting to go seriously wrong for him. To start with, he took a week longer than his competitors to accept the contract. Benson, Lonsdale and Co., the bankers that had been brought into the deal started to get over cautious and this caused them to under-invest. As a result of this another of his backers developed cold feet at the last minute and pulled out altogether.

With the imminent collapse of the Collins consortium, the ITA were still reluctant to hand over a contract to the Littler/Grade group and they held out for many months, possibly hoping that Collins might find suitable backers in time. But the ITA didn't count on the shrewd business mind of Lew Grade. The ITC board realising they were now in a very strong bargaining position moved in at the precise time that the Collins bid fell apart and offered a merger on a fifty-fifty partnership basis with ITC remaining in existence as a production company in their own right. This meant that they would be able to make their own programmes and then sell them to a company that they owned 50 per cent of, and then sell those shows to other TV stations around the world, for which they would receive full revenue.

The new company was to be called the Associated Broadcasting Company, but this was quickly changed to Associated TeleVision (ATV), when the Associated British Cinemas group objected to the use of the company's ABC logo.

Prince Littler became Chairman of the Board as well as remaining Chairman of ITC and Lew Grade remained Managing Director of ITC. With the weight of Collins' reputation on their side, the newly formed ATV were awarded the contract to broadcast London's weekend programmes and the weekday schedule in the Midlands. Collins was back in television once again, but in the company of Grade, Littler and Parnell it was a much-diminished role than he had previously hoped for.

Although ITC had a strong board of people who had been in show business for many years, they still lacked programme-making experience. Therefore, Harry Alan Towers, who had been producing programmes for Radio Luxembourg was drafted in, director Bill Ward, technical engineer Terence MacNamara, Keith Rogers, Frank Beale and Leonard Matthews all followed. The ailing Wood Green Empire was purchased from Stoll Moss and converted into a TV studio. However, as Lew Grade himself freely admitted in his autobiography (Still Dancing: My Story) the board was a far from happy one. "There appeared to be two factions - the Robert Renwick C.O. Stanley/Norman Collins group, and the Prince Littler/Val Parnell/Lew Grade group. Whenever we had board meetings there were constant arguments between C.O. Stanley and Harry Towers. Towers kept on blaming Pye for delays in the delivery of equipment and naturally this upset C.O. Stanley very much. The two men disliked each other intensely."

But the board agreed to persevere in the interests of getting the company prepared to go on the air and in due course they took offices in Television House in London's Kingsway, which had formerly been the home of the Air Ministry. The BBC too prepared for commercial television, and in the weeks leading up to opening night at ITV a series of articles printed in the Radio Times were specifically tailored to attack the regional programming strategy of commercial television. In a full-page article, the Corporation's Director General Sir George Barnes wrote; "BBC covers the country. It's not a boast it's true; 92 out of 100 homes watch the BBC."

"The first three transmitters, between them, will serve less than half the population."

It was true that in its early days ITV would only be able to reach 13,000,000 people living in the London area, which at that time was less than a quarter of the population. In an article that these days would come under the heading Frequently Asked Questions the weekly publication TV Mirror addressed the concerns of television viewers. "How long will I have to wait for ITV? If you live in or around Manchester and Birmingham, the answer is not long. Let's say until the early part of 1956. If you do not live in either of these areas, we can only recommend you to patience and BBC TV."

"The first three transmitters, between them, will serve less than half the population. The ITA hopes that within four or five years seventy-five per cent of people now served by ITA will be able to receive commercial. Scotland, South Wales and Yorkshire come high on the list of priorities. They will probably get the service late in 1956 or early in 1957. After them, stations may be set up to cover the North-East Coast, the South-West, the Portsmouth area and Northern Island." However, this advice came with a certain amount of caution. "We should point out that these are areas ITA hopeto serve. Whether or not they get commercial TV largely depends on whether a programme contractor comes forward offering to operate the site."

Viewing the ITV broadcasts on Channel 9 (the designated number on the TV dial) was not as uncomplicated as it seemed even if the viewer did live within the receivable transmission area, as most televisions first had to be adapted (or tuned), as TV Mirror went to great pains to explain; "To have your TV adapted will cost, on average about £12. If you live close to a transmitter and have a set made in the last four years, the conversion should cost no more than £3 or £4. If you are about twenty miles away, the aerial alone may cost £10. In some cases the adaptation may amount to £30.

"If you live just outside the official transmission area it may be worth making enquiries with your dealer. Although the range of the Croydon transmitter is supposed to be forty miles, signals have been received as far away as Hastings, which is seventy miles from Croydon. On the other hand, you may live almost next door to a transmitter and be unable to receive it. If you live close behind a gasometer or steep hill you would be well advised to ask for a test before paying for the conversion."

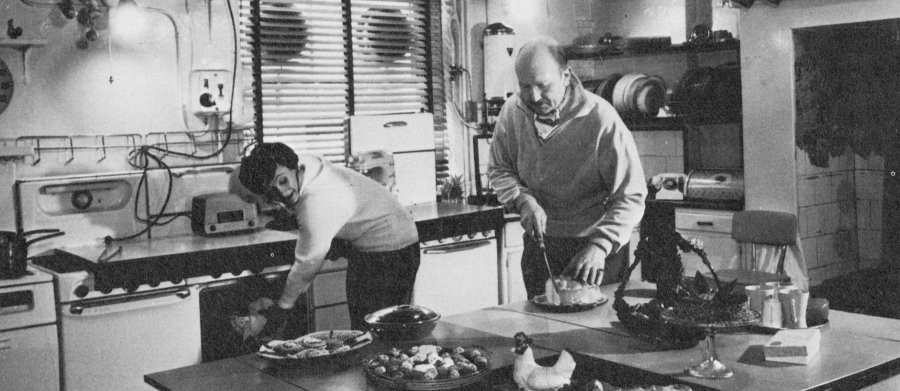

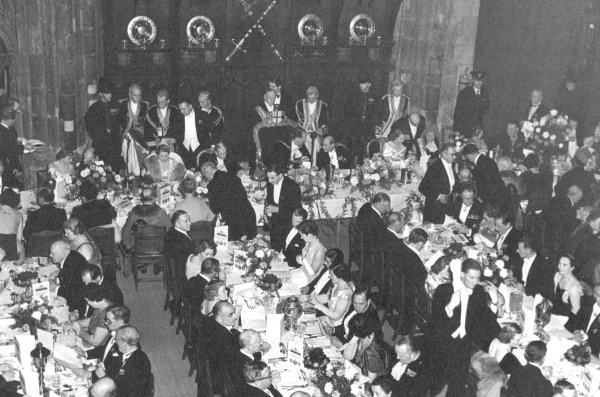

Even with so many questions still to be answered commercial television opened at 7.15pm on Thursday 22 September 1955 with Rediffusion being the first independent company to take to the airwaves with a televised grand opening ceremony at London's Guildhall. The 45 minute show watched the guests arrive, listened to an overture (In London Town) followed by the National Anthem by the Halle Orchestra and heard inaugural speeches by the Lord Mayor of London, the Postmaster-General and Sir Kenneth Clark (amongst others). This was followed at 8.00pm by a show from the ABC Television Theatre called Variety, hosted by Jack Jackson, who, at 8.12pm announced, "...and here's the moment you have all been waiting for; it's time for a natural break."

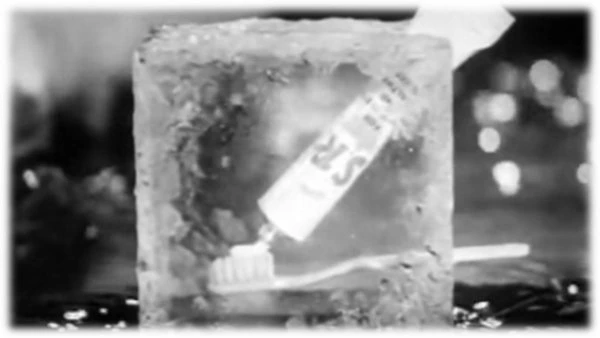

Advertisers were charged a premium of £1,500 a minute for the honour of appearing on that first night and such was the demand for one of the 23 slots available that lots were drawn to decide who’s would be shown first. In the event Gibbs SR toothpaste was drawn out of the hat first and was therefore the first advertisement shown on commercial television. During the course of the evening ads for Cadbury's Drinking Chocolate, Dunlop Tyres, Lux, Surf, Brillo, Shredded Wheat, Ford and Woman Magazine were broadcast. Of the first commercial one critic wrote the following day; "I feel neither depraved nor uplifted...I've already forgotten the name of the toothpaste." The Daily Worker, no doubt taking the same dim view of commercial television as the Labour Party whose attitudes it voiced, ran a headline announcing "Too much marge and toothpaste," whilst The Observer noted that there "wasn't enough vulgarity to attack the ads". The Times referred to the natural breaks as "comic interruptions" and a visiting US critic from The New York Times said that the adverts were "a paragon of British understatement and restraint."

However, the critics were neither indifferent nor complimentary about Rediffusion's first night and regarded the programming on offer as generally lacklustre and poor. Following the variety show the evening's schedule continued with drama excerpts linked by the actor Robert Morley, a boxing match from Shoreditch, a fifteen minute newsreel and a party at the Mayfair Hotel where, according to Lew Grade, the Chairman of Rediffusion, Stuart MacLean, came up to him and told him smugly, "When you go broke we'll buy you out."

A quarter of the viewing public remained loyal to the BBC and eleven per cent didn't even bother to turn on.

The BBC countered with a masterstroke to steal its rival’s thunder. Since 1950 radio listeners had followed the goings on in the fictional county of Ambridge in a series of 15-minute, nightly episodes of The Archers. On the evening that commercial television started, the Archer's broadcast its most dramatic episode ever, when favourite character Grace Archer was killed in a fire. The BBC, of course, claimed that the timing of this incident was pure coincidence.

In any event the viewing figures for that first night were somewhat disappointing. Only 170,000 TV sets were equipped to pick up Channel 9 in the London area and of these only 100,000 tuned in. A quarter of the viewing public remained loyal to the BBC and eleven per cent didn't even bother to turn on.

Two days later ATV kicked off its Saturday night broadcast at 7.30 with The Adventures of Robin Hood, the series that Lew Grade had commissioned. A variety show, Val Parnell's Saturday Spectacular and then a film series followed this. Sunday night's entertainment programming opened with the US import I Love Lucy at 7.30 followed by Sunday Night at the London Palladium, hosted by the popular comedian/entertainer Tommy Trinder. This was followed by a drama running from one to two and a half hours. ATV found it had a gap between 6.30 and 7.30 before "Lucy" started, and at the suggestion of Lew Grade they tried out a one-hour religious programme, something that had never been done on television before. It proved extraordinarily successful and won the praise of church leaders up and down the country. In fact the weekend programming by ATV proved to be a massive hit with London's viewers, and by the end of the year Sunday Night at the London Palladium, a programme that wouldn't have been possible just months before, had become the capital's top rated programme with an audience percentage of 84. Lew Grade would later claim that, "ATV changed the whole complexion of television with our adventurous programming." It proved to be no idle boast.

If the BBC had taken the introduction of commercial television with only a small amount of trepidation there is every chance that the panic bells were ringing very loudly at the Corporation when, by the year’s end, only two BBC shows featured in London's top twenty. I Love Lucy, already a major hit in the USA was placed at number 3 with another US show, Dragnet at 4. Robin Hood, essentially a children's series, was sixth, one place behind Friday night quiz show Take Your Pick. The best the BBC had to offer was a show called Highland Fling, which came in at number 14 with an audience share of 68 per cent.

But the costs to ATV were heavy. Although it had a willing audience and revenue from advertisers there were not that many in those early days. London was the only commercial station on the air until the Midlands came on in March of 1956 - with Lancashire going live in June of that year. ATV's financial situation was becoming critical, and by the end of December their finances were stretched to crisis point and by March 1956 they had run out of money.

At first, the signs were encouraging. In the first three months of transmission the sales of ITV capable sets more than doubled to around 500,00. But the government, increasingly aware that people were borrowing more than they could pay back, clamped down on hire purchases and demanded nine months advance payment on all rental agreements on any new TV sets. It was a blow to ITV.

The ITA had already warned any new TV company to expect heavy losses in their first year, a lesser loss in the second year and a break-even figure in the third. Only then would the broadcasters begin to show a profit, and, if everything went to plan, would be able to turn over a healthy profit for the remainder of their ten-year contracts. But the companies involved underestimated just how quickly and how hard that loss would impact. Many backers tried to bail out.

At this point ATV sold a number of its shares to The Daily Mirror Group, 29 per cent of ordinary shares and 25 per cent of voting shares. The rest of the board put up the additional capital, Lew Grade having to sell his wife's jewellery. Once the Midlands began its transmission, advertisement revenues began to pick up. By the time Lancashire joined, the other commercial companies’ TV coverage comprised 75 per cent of the country and for the first time the money began to roll in. ITC then won a deal with Roy Thomson, (who eventually went on to own the Thomson Group of Newspapers), whose company had won the franchise for Scotland. The contract was to supply the entire output for Scottish TV at a fee of £1 million per annum for ten years. By the end of 1957 it was decided by the board that there might be a conflict of interest between the two partner companies, and so ATV bought ITC, making it a wholly owned subsidiary.

Chairman of the Mirror Group was Cecil King who had already expressed his interest in commercial television. His plan, which he had privately boasted, was to wait for the first bankruptcies among the ITV franchise holders and move in and pick up the pieces. He even went as far as beginning a newspaper campaign to discredit the companies by alleging right-wing political bias and demanding that the ITA should call in all the contracts and start again from scratch. But when that plan didn't work, he stepped in very quickly with over £400,000 of investment from the Mirror Group. As it turned out the capital investment was never called upon and the Mirror Group now found themselves with a healthy 36 per cent of the shares.

One casualty of the crisis was Harry Alan Towers. His departure from ATV left the doors open for Val Parnell and Lew Grade to take over the day-to-day planning of the station's schedules. It was Grade who made the biggest impact. Already responsible for The Adventures of Robin Hood and the hugely successful Sunday Night At The London Palladium, a Sunday night slot that had been regarded as the domain of the BBC and their Sunday play, Grade's knack of knowing exactly what the public wanted would eventually make him the most powerful man in the British entertainment industry.

1956 was a good year for commercial television in London, which now claimed to dominate the viewer ratings top twenty 100 per cent. It was a trend that would spread across the country as each new station opened their airways and became the dominant broadcaster for that region. And if figures presented at that time were accurate it was an absolute dominance that would last until 1962 when the BBC's detective series Maigret finally managed to break into the top twenty at number 14 with an average viewing audience of 6.94 million. (Figures were released in their millions -as opposed to a percentage- from 1957). It wasn't until the following year that the BBC managed to make any impact on the top twenty with 7 entries (the highest being Steptoe and Son at number 3 with 8.79 million) and not until 1969 that it reclaimed the top spot with that year's Miss World Contest.

However, even former critics of the BBC, such as Kenneth Baily, were ready to defend the Corporation. 'All viewing audiences should surely be seen in the context of the very considerable total possible TV public', he wrote in 1960. He went on: 'Even here, in the realm of what ought to be fairly exact statistics, we do not know the actual position. For TAM, the audience researchers, who are paid for their work by the commercial contractors, put the BBC's gain of audience at an average of three to five per cent throughout most of 1960. The BBC's own audience research system claims that the swing to the BBC is much more and says it can at times be a twenty per cent gain from ITV. Indeed, Mr. Gerald Beadle, chief of BBC Television has told an American audience that viewing today is often divided fifty-fifty between ITV and BBC. Whom do we believe?'

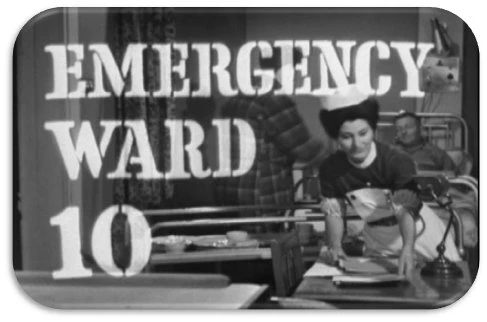

Even Baily was confused by the different claims at that time. However, there was one thing he was sure about-and just a few years after he had lambasted the BBC's programming policy, he was ready to turn his critical eye on the commercial channels. 'The so-called "documentary-story" of ITV creation, like Emergency-Ward 10 and Probation Officer are window-dressing to try to persuade politicians, the Church, and the intellectual "establishment" that commercial TV is informing mass publics at peak hours', he wrote at that time. He went on to observe that Emergency-Ward 10 in particular was about as informative as a woman's magazine story and as for Probation Officer he wrote; 'once it has reiterated the cliché that bad homes breed delinquents of all ages, it really has nothing else to teach about the causes of rebellion against order, or the difficulties, failures and successes of reformative jurisprudence.' (In fact, Baily was incorrect citing ITV as the creators of documentary-stories as can be seen in the article Cops on the Box, which clearly indicates how the BBC adapted this genre.)

Many critics may still have regarded television as a medium that was there to educate rather than entertain, but as the 1950's drew to a close Independent Television firmly established itself as the viewer’s, if not always the critic’s, favourite. It soon became known as The People's Channel. The BBC would find itself having to adapt in order to re-establish itself and meet the demands of serious competition -and that could only benefit the viewer. Commercial television had had an exceedingly long and bumpy ride from the early days of its conception through to its eventual arrival. But it had arrived. And it was here to stay...but there would be plenty more bumps ahead.

Laurence Marcus October 2005. Reference Sources: TV Mirror Annual, The Television Barons by Jack Tinker (1980), Wikipedia, The Guinness Book of TV Facts and Feats, The Television Annual (various editions), Still Dancing by Lew Grade, Ian Freeman (in conversation), ITV: The People's Channel by Simon Cherry.

Previous Chapter: The Independent Applicants Next Chapter: TV Advertising - Boosting the Economy

Published on April 28th, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.