Cops On the Box

"The scripted crime shows that we watch on our TV screens today owe much to television's early uncertainty, experimentation and innovation and a combination of styles which were forged in the 1950s and reached fruition in the 1960s."

In the 1950/51 Television Annual, in a chapter entitled Real Life in Pictures, the article writer explains the production of what at that time was still a relatively new addition to the TV schedules; the documentary film. "The outside television camera has so far made only a small contribution to television documentary programmes. These programmes have more often than not emanated from inside the Alexandra Palace studio. Rather than being a realistic portrayal, the television documentary programme looks as though it is going to be a carefully produced artistic interpretation, with actors and actresses taking the place of the people actually concerned. It was found out early on in television that it requires the art of the trained actor to give a realistic impression of ordinary people going about their everyday business." By the following year, the same annual publication recorded in the chapter Seeing Facts; "Not many (documentaries) are produced in one year. For some time those which were produced stuck rather to one field of life: crime, its detection, and the workings of justice in the courts."

The idea of scripted drama presented as documentary was not a new one in the early fifties, nor did it start on television. A perfect example is Humphrey Jennings' 1943 production 'Fires Were Started' a Ministry of Home Security backed propaganda film made to boost morale on the homefront during the Second World War, and show the courageous work of the fire service in bomb blitzed London. According to Derek Malcolm in the Guardian: "In other hands, ('Fire Were Started') would have been mere propaganda made to stiffen the national mood. But in his, the images of Britain were often so powerful and so moving that people would be in tears watching them."

Although these dramatised reconstructions were a far cry from the type of scripted fictional drama that Elstree or Hollywood were producing at that time, or the type of drama series that became popular on our screens by the late 1950s and early 1960s, it will soon be seen how they influenced the emergence of one of the most popular genres of television drama: The police procedural or 'cop show'. In her book 'Beyond Dixon of Dock Green' author Susan Sydney-Smith notes: "In terms of mapping the evolution of the story-documentary, a significant entry in Radio Times (1948) lists a separate item within (the fortnightly magazine programme) Kaleidoscope. It describes itself as 'a story-documentary, written in co-operation with Scotland Yard, to explain some of the ingenious frauds that have recently been worked on the unwary.' It's Your Money They're After, earlier produced on radio, was a dramatised reconstruction concerning post-war fraudsters." According to Sydney-Smith "Scotland Yard and crime were a prime source for institutional dramatised reconstructions, combining popularity with moral instruction, and from which grew the ordinary, British television police series."

It was still early days for television with the BBC only having been back on the air for three years having closed down television broadcasting at the outbreak of the Second World War, and the move from docu-drama towards full dramatisation would be a gradual one. One of the first crime series on British television was War on Crime a 1950 six-part docu-drama produced by Robert Barr and written by Guy Morgan and Percy Hoskins.

The idea for the series came about when Morgan was conducting research at Scotland Yard for a Twentieth Century Fox film, and realised the potentially dramatic material that was available in the Metropolitan Police's crime files. He discussed the idea with Barr, and they enlisted Hoskins, a former crime reporter for the Daily Express, who was on good terms with a number of senior police officers. The first episode, 'Gold Thieves', recounted the true story of a bullion robbery in 1948 at Heathrow Airport, where thieves tried to steal gold bullion to the value of a quarter of a million pounds, but were ambushed by officers. The second story, 'Woman Unknown', was introduced, like all the others in the series, by a voice-over. In this case, it told viewers: "This is the story of a murder. A murder, apparently, without a clue. Unpremeditated and followed by meticulous skill in concealment, the detection of which, for sheer tenacity and perseverance, has few equals in the records of Scotland Yard." Having set the scene, the story then unfolds in dramatised format, using actors to show the original police investigation in the case of a woman's body, washed up in a London canal, and how they go through the processes of identification, the means of finding out how she died, and by whose hands. The murder, for petty theft, of an Oxford widow, was reconstructed to show how the culprit was finally brought to justice entirely by circumstantial evidence.

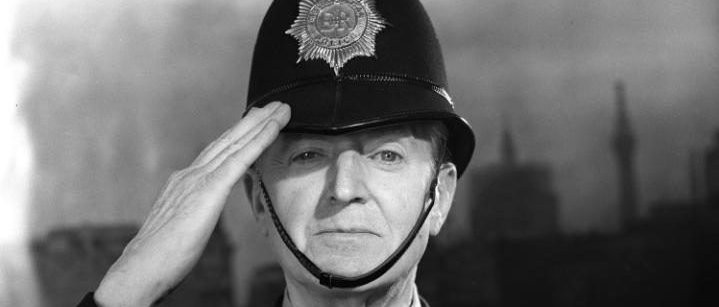

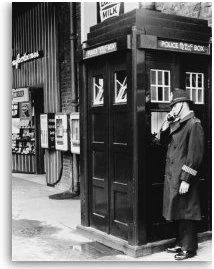

Another programme in the series revealed the use of pathology in crime detection, and was based on the real facts behind a number of sensational murder arrests, including that of John George Haigh, the acid-bath murderer. As the Television Annual 1950/51 recorded: "In all programmes viewers saw the criminals and their confederates; their victims; the police, the star detectives from Scotland Yard-all characterized by actors and actresses. Not one real-life policeman or Scotland Yard official ever appeared on screen." This was, to all intents and purposes a scripted drama series that had little to do with the term documentary as we would understand it today. Each programme was introduced with the caption War on Crime with a flashing light atop a police box, rising behind it, and a policeman walking by the box. War on Crime was broadcast monthly, and its influence can be clearly understood on police procedural series' that followed it in the 1950s and beyond.

The next police based docu-drama, produced by the BBC the following year was I Made News, a landmark TV series for the BBC in several respects. Firstly, it was the first time that directors had been used in television. Previously on both radio and television the accepted format was for writer-producers to direct their own shows. One of the criticisms of War on Crime was that as it was only shown monthly - it failed to build up any audience loyalty. As a result, producer Robert Barr was given the job of setting up a production unit capable of turning out weekly dramas of the type that were then being produced in America.

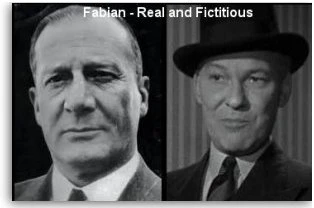

I Made News was to be the case study for this new production process, turning out 12 weekly half-hour docu-dramas. Due to its experimental nature, I Made News was more concerned with quantity than quality, a move that proved to be quite controversial within the BBC itself. Critics too, appeared to be divided. The News of the World commented: "I Made News has only occasionally made good television. As the creator of 'Raffles' may not have said, there's no police like Holmes." The series centred round criminal investigations but didn't restrict itself to the British police force. Some episodes were set in Holland, others involved the FBI and the leading investigator from those cases were invited to top and tail the story that had been told like War on Crime, in dramatic reconstruction. The face of the Metropolitan Police was Robert Fabian whose exploits would later form the BBC series Fabian of Scotland Yard (aka Fabian of the Yard). Susan Sydney-Smith writes that I Made News "both increased production and considerably enhanced the BBC's ability to compete with the arrival of Independent Television."

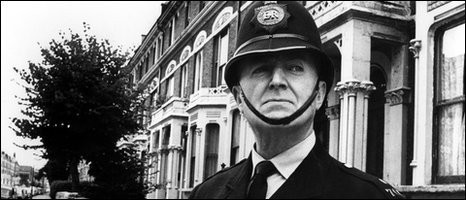

Building on the experience gained on I Made the News, the BBC produced another six-part series, in 1952, called Pilgrim Street. This series, made in co-operation with Scotland Yard, contained many of the elements that would eventually be employed in the BBC's best remembered police series; Dixon of Dock Green. Pilgrim Street was made once again by the BBC documentary department. The difference was, where War on Crime and I Made News focused on high-profile cases and were centred round the Criminal Investigation Department officers of Scotland Yard, Pilgrim Street was the first of these docu-dramas to revolve around the work of policemen at a suburban police station, and to feature cases, as the Radio Times of 1952 reported, that "never find their way into the pages of the Commissioner's Report and in which the police act as helpers and protectors of the public."

The fictitious Pilgrim Street police station was, however, just a stones-throw from Scotland Yard as the opening narrative indicated: "Our manor - our ground. It's as varied as anything in London. The railway station is in the centre there, and around it are cinemas, the shopping streets, the wharehouses, the pubs, the pawnbrokers, and the little streets. Up here, luxury flats, spacious squares and gardens, and embassies. Skirting it all, the Embankment and the river. That's our ground. Our Manor. And right here is our station: Pilgrim Street." The series was originally to have been called The Blue Lamp, however BBC bosses were concerned about using a title already used by the cinema for a feature film, even though the film was undoubtedly the inspiration for this television version. Clearly producer Robert Barr was hoping the short run (Pilgrim Street ran from June to July and was produced at the newly acquired Lime Grove studios) would give rise to a long running series. However, critical reaction and lack of support from his boss, Cecil McGivern, put paid the that idea. One critic described Pilgrim Street as "ordinary to the point of dullness." Nonetheless, Pilgrim Street is an important programme in the development of the British TV police procedural drama genre being the first steps towards a series featuring the exploits of 'an ordinary copper.'

That 'ordinary copper' first appeared not on our television screen but in the cinema. Released in early 1950, The Blue Lamp featured Jack Warner as police constable George Dixon. Scripted by ex-policeman T.E.B. Clarke (from a story by Ted Willis and Jan Read), at the outset the film is similar in style and presentation to Fires Were Started. Opening in documentary style, the viewer is introduced to a policeman's lot through the eyes of new recruit Andy Mitchell (actor Jimmy Handley) as he begins his first shift at Paddington Green. Writer Guy Savage observes how "The Blue Lamp finds London police directing traffic, giving directions, finding lost dogs, and even singing in the police choir. The grossest sin committed by the police at the Paddington Green station is a tendency to park themselves in the police cafeteria and drink a few too many cups of tea."

Having established the day-to-day life of the ordinary copper the film then shifts to more serious matters and it's at this point it stops being mere documentary and becomes what we have now come to know as docu-drama, with more of an emphasis on the drama. Guy Savage sees a materialisation of the films darker overtones when he writes: "The film carefully laces the action with the lurking shadow of WWII--one woman arrives at the police station to file a lost ration card report, and in another scene, street urchins play amidst a bombed-out London street. The film argues that the social upheaval of WWII has fermented an environment which fosters the emergence of delinquents."

It is one such delinquent, set on a life of crime, that has the biggest impact. When George Dixon is gunned down by the young criminal played by Dirk Bogarde. Dixon’s shooting is shocking and unexpected. Fifty years on, it's hard to appreciate just how shocking it was considered by British audiences. And because of it The Blue Lamp is a seminal film in the history of British cinema. It is no surprise that the dramatic aspects of the story were more prominent in The Blue Lamp than previous documentaries. In 1951 the Central Office of Information, established in 1946 as the successor to the wartime Ministry of Information, was closed. There would be no more 'public information' films in the cinema, but television would borrow from the genre for a few more years.

The first ever British made filmed series, shot in 1954 by Trinity Productions for the BBC and consisting of 39 black and white episodes, Fabian of Scotland Yard has been described as Britain's first generation of the TV detective. To give it credibility, the series was (once again) based on real crimes, or stories from police files from Scotland Yard and in particular (or so it was alleged) on the investigations of former celebrated Yard detective Robert Fabian. Fabian was played in each episode by Bruce Seton but the real-life Fabian turned up at the end of each episode to round it off similar in style to George Dixon. Fabian of the Yard was the last BBC series to adopt the docu-drama approach to police shows and in 1955 the genre went to fully scripted drama with Dixon of Dock Green, the TV series inspired by The Blue Lamp but owing as much to Pilgrim Street. Debuting with 'PC Crawford's First Pinch', the series begins the same way as the film. Instead of Andy Mitchell's first day on the beat the now 'resurrected from the dead' George Dixon found himself mentoring new recruit Andy Crawford. However, in spite of the film's success the television debut of Dixon left both viewers and critics decidedly unimpressed. Comments on the first programme included 'tame', 'humdrum' and 'lacking any action.' However, by the sixth week the BBC's audience appreciation report indicated that the series was winning viewers over very quickly with a 49% increase from week one. By 1957 the Radio Times was reporting that Dixon of Dock Green had been mentioned in the House of Commons and was responsible for an increase in those applying to join the police. In the end, the programme ran for 21 years and as Susan Sydney-Smith noted: (Dixon of Dock Green) "..introduced new, increasingly rationalised methods of working" in television and introduced the terminology whereby a single series run is known as 'a season'. With the success of Dixon of Dock Green police procedural serials began to appear on television with great regularity. 1961's Jacks and Knaves paved the way for regional crime series' rather than them being based solely in London.

The scripted crime shows that we watch on our screens TV today owe much to television's early uncertainty, experimentation and innovation and a combination of styles which were forged in the 1950s and reached fruition in the 1960s. And since then, the genre, which is arguably the most durable of them all, has continued to develop and will no doubt continue to do so.

Link: http://www.noiroftheweek.com/2011/07/blue-lamp-1950.html (Guy Savage )

Published on February 17th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus (2014) for Television Heaven.