Mavericks, Mavericks Everywhere

Fat Rab is one mean cop. But at home his life is a mess. His marriage is in tatters and he rarely gets to see his kids. The only thing that keeps him sober - most of the time - is the job. The job is everything. But Fat Rab lives by his own code and doesn’t play by the rules. Fat Rab is a maverick, a cop like no other...

I’ve just made Fat Rab up; he doesn’t exist, not even as a fictional character. But if he was a cop in a telly drama or series of crime novels, the press releases would describe him pretty much as I’ve done. Yet, as a maverick, he’d actually be just like almost every other TV cop. Fictional detectives generally try to win our attention by pointedly not playing it by the book. You’re inclined to wonder, since they’re all so rebellious, who exactly is left for them to rebel against? And what’s the point of rules that nobody plays by?

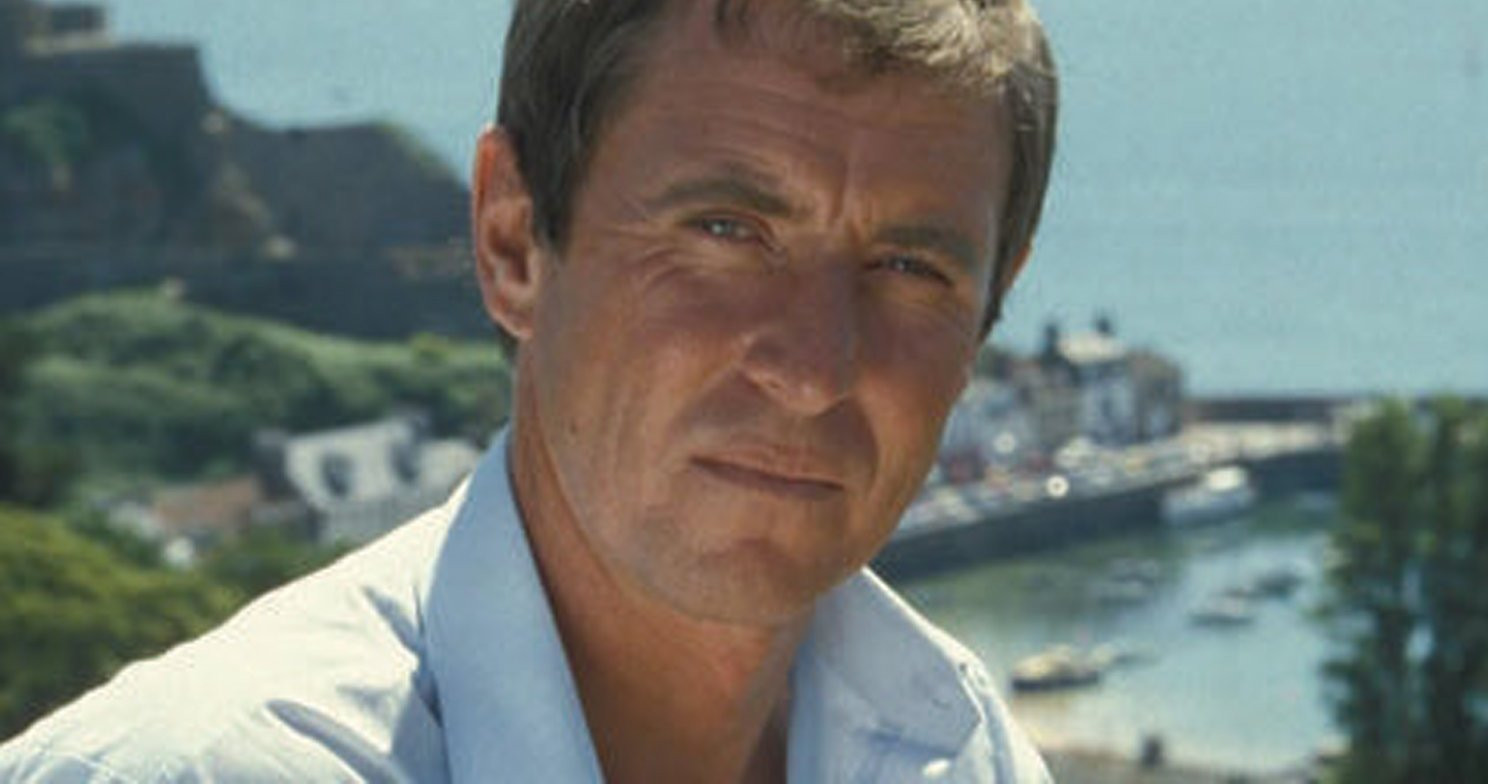

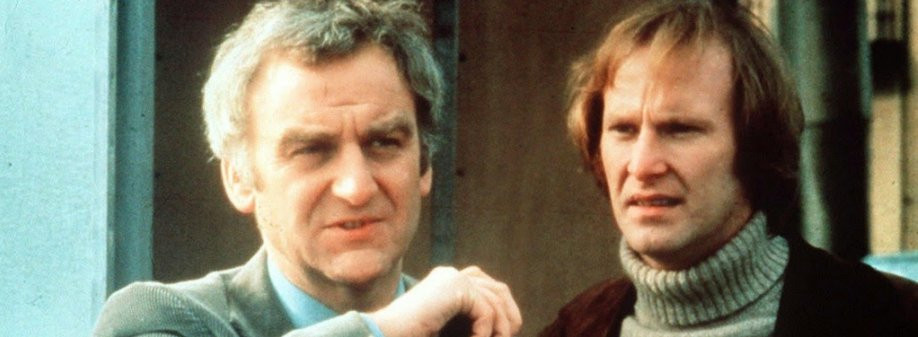

Take Maverick Cop Jack Regan from legendary 1970s telly series, The Sweeney (more recently resuscitated - though not very well - in a film starring Ray Winstone). Regan drinks too much, he smokes too much, his marriage is over, he struggles to keep in touch with his daughter, his romantic life is a succession of affectionless, short-term drunken liaisons. And since his private life is such a wreck, the job, being a copper, getting the rubbish off the streets and into the nick without worrying too much about the ethical niceties, is everything. Without the job, there wouldn’t be much of Jack Regan left. ‘He’ll be back,’ says his boss, Haskins, as Regan storms off after resigning in the last ever episode of the programme, ‘he needs the job like an alcoholic needs booze.’

Regan, of course, was played by John Thaw. These days, Thaw is probably even better remembered for his title role in Inspector Morse. Morse could not be more different from Jack Regan; he prefers Wagner to strip clubs, Thomas Hardy to seedy boozers, real ale to supermarket lager and opera singers to cheap women down the local. However, his cerebral approach and haughty manner alienate him from superiors and colleagues. He’s a different kind of maverick to Jack Regan, but he’s a maverick all right. All the same, if Regan and Morse ever met, they really wouldn’t get on.

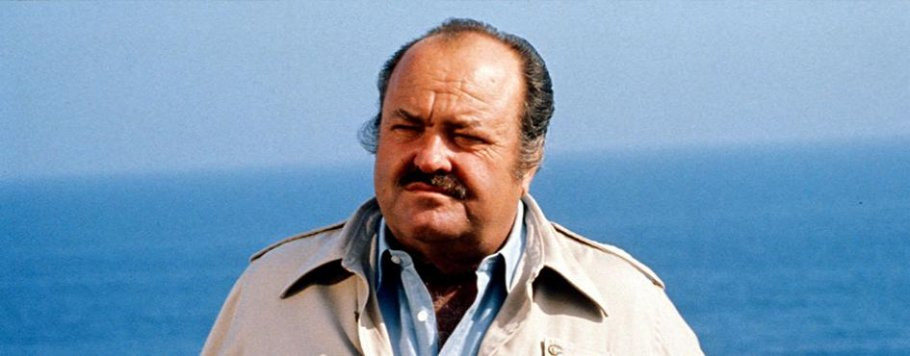

Morse began on paper in Colin Dexter’s novels, but it’s worth drawing a distinction between detectives as they appear on screen and on the page. The character often develops quite differently on the telly. Consider, for example, Dalziel and Pascoe. In both Reginald Hill’s novels and the BBC series, Andy Dalziel is the maverick’s maverick, a vulgar, boorish, insolent, fat, wind-breaking slob (brilliantly played by the much-missed Warren Clarke) whose only discernible positive quality is his determination to bang up the bad guys. Peter Pascoe, by contrast, his graduate-entry sidekick, is decent and respects the rules; he’s also married to Dalziel’s polar opposite, a tiresome, right-on, Guardian-reading college lecturer. Cue friction between maverick Dalziel and Peter Pascoe, and daggers drawn between Dalziel and Mrs Pascoe; Dalziel may be truly loathsome, but I think most people would still side with him in that battle of wills. In the novels, the Pascoes remained together, but on the screen Mrs Pascoe was mercifully dispatched - not quite killed off, but separated from her husband and posted offscreen to Canada. Peter Pascoe was freed, then, to slowly, barely perceptibly, morph into a pale imitation of Andy Dalziel. By the end of the series, Pascoe was definitely becoming a maverick. I saw Colin Buchanan, the actor who played Pascoe, on stage a few months ago; he’s starting to look a bit like Warren Clarke’s Dalziel.

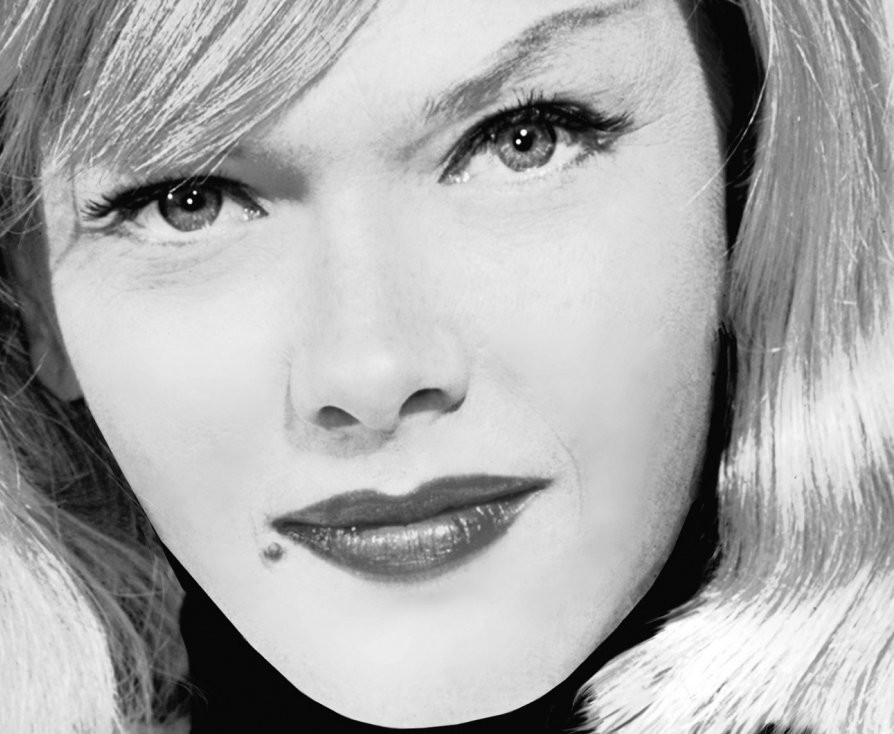

So in some telly incarnations of literary detectives, the maverick factor has to be bigged up. In other instances, though, it gets cooled down. Jack Frost, played by David Jason in A Touch of Frost, is a classic scruffy, shambolic maverick (see also Columbo and Rebus), a thorn in the side of his superior, Superintendent Mullet, with a dread of ever doing any paperwork. But the Frost of RD Wingfield’s novels was also chain-smoking, foul-mouthed and a much less genial character. To suit telly, and to match David Jason’s persona, Frost had to become a nicer maverick.

Mavericks can be nice; they don’t have to be grumpy or insolent or unprincipled or rude or permanently sozzled. In Pie in the Sky, Henry Crabbe (Richard Griffiths) is gentle, decent and likeable. But he’s a maverick because he doesn’t want to be a cop any more, and would prefer to retire and concentrate on running his restaurant. However, his twisted superior Freddie Fisher has some (mistaken but convincing) dirt on Henry and blackmails him into staying in the force. So Henry uses his considerable policing skills to solve crimes for which Fisher takes all the credit. Henry must make do with genteel insolence towards his corrupt but gormless superior. This twist, together with good writing and splendid performances, makes this series an unlikely delight despite its bonkers premise - He’s a COP! But he’s also a CHEF!

Yet some telly cops are not remotely maverick. Take Tom Barnaby (John Nettles) of Midsomer Murders; he’s a devoted and loving husband with a devoted and loving wife. They have a beautiful and talented daughter, Cully, who herself had become happily married by the time the family bowed out of the series. Tom Barnaby is a good copper and one who usually sticks to the book, and even occasionally has to threaten to throw said book at his young sidekicks - successively Troy, Scott and Jones - when they flirt with maverick behaviour.

Barnaby may indeed be a model citizen and a model copper. Yet he presides over a manor with an unparalleled rate of grisly and gruesome murders. And generally the slayings don’t stop just because Barnaby is on the case and hot on the trail of the perp.

Perhaps, then, maverick coppers are the price fictional communities must pay in order to have reasonable levels of crime prevention and detection. It’s all very well to rail against police corruption and brutality, but be careful what you wish for. If television is telling us anything, it’s that if our coppers are as decent as Barnaby, none of us will ever sleep easily in their beds again.

David McVey (2016)

David McVey lectures in Communication at New College Lanarkshire. He has published over 100 short stories and a great deal of non-fiction that ranges from academic papers to a column in the match programme of his local non-league football team.

Published on February 19th, 2019. Written by David McVey (2016) for Television Heaven.