Red Dwarf - Three Million Years On

On the 15 February 1988, a peculiar low-budget series had its first broadcast on BBC2. Red Dwarf was an, at-the-time, rare combination of science fiction and situation comedy, a genre that is hard to pull off successfully. The series had a troubled gestation and few at the BBC expected it to be a success.

Thirty years later, Red Dwarf is a hugely successful television phenomenon. The most-exported series to originate on BBC2 (it's huge in the former Czechoslovakia), after a long hiatus it has experienced a resurgence on the digital channel Dave. Over the years it has won multiple awards, from an International Emmy for Outstanding Popular Arts Programme, a Royal Television Society award for special effects, a British Comedy Award and several British Comedy Guide awards. The series has developed a huge fanbase, becoming both a popular and cult hit, with a fan club and an annual convention (Dimension Jump, looking at its twentieth event this autumn).

It's not at all bad for a series that very nearly didn't get made at all. Science fiction was a hard sell at the BBC in the late 80s. Doctor Who was on borrowed time, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was of the past and the idea of a sci-fi sitcom was viewed with derision and as a better subject for kids' TV. It was a tough sell for Rob Grant and Doug Naylor, long-time writing partners and creators of the series. In fairness, it's not hard to see why the programme commissioners might have baulked at the idea. It's a series with a strange and elaborate central concept. The two lowest-ranking members of the crew of a gigantic spaceship are the central characters. The lowest of the low, Lister, is put into suspended animation for smuggling a pet cat onboard, while his superior, Rimmer, fouls up the replacement of a vital drive plate. The resultant radiation leak wipes out the entire crew, save Lister, who is protected by the stasis field. Three million years later, with the radiation at a safe level, ship's computer Holly revives Lister. Wary of him losing his sanity, alone in deep space, Holly resurrects Rimmer as a hologram. Meanwhile, Lister's pregnant cat, sealed away in the hold, has given rise to a race of highly-evolved feline humanoids, the last of whom makes the fourth member of the core characters.

That's a tough concept to sum up easily, but the complex trappings boil down to something very simple: The Odd Couple in space. Lister is a down-and-out slob, barely capable of looking after himself in spite of his innate intelligence, who eats vindaloo daily and ends up wearing most of it. He's lazy, dirty, out-of-shape and disgusting, and he's the hero! Arnold Rimmer, his immediate superior and bunkmate, is the exact opposite: precise, anal, career-obsessed, a military enthusiast, always has a pen. They despise each other. It's a classic sitcom set-up, forcing two incompatible people to live together – in this case, probably forever.

Grant and Naylor trialled the basis of the series in the early 80s radio series Son of Cliché with the sketch “Dave Hollins: Space Cadet,” which led to a short series-within-a-series of Dave Hollins sketches. In this, Dave Hollins is the last man alive, lost in space (anything from three hundred to seven billion years in the future, depending on the episode) with only ship's computer Hab as company. The basic idea's there, but it's missing that key odd couple element. It has obvious influences in Dark Star and 2001: A Space Odyssey, a clear sci-fi parody.

In developing the script for television, the writers made significant changes. The time scale was settled on as a comparatively modest three million years, although Lister's home century has never been cleared up. Dave Hollins became Dave Lister, Hab became Holly. Wary of including robots and aliens in the series, considering them sci-fi clichés, the writers came up with the idea of a hologram and a cat person, expanding the characters while technically keeping Lister as the last human being. The backstory for the series was established in more depth: Lister and Rimmer worked for the Space Corps, as part of the crew for the Jupiter Mining Corporation ship Red Dwarf. Lister held dreams of settling down with the widely desired navigation officer, Kristine Kochanski. Rimmer came from a successful family of officers, all of whom looked down on him because of his lowly position as Second Technician. Holly was an advanced AI with an IQ of 6000 (the same IQ as six thousand PE teachers). The script for the pilot episode was complete by 1983, but wasn't picked up until 1986, when it was championed by Paul Jackson, who used his position as executive producer and director to insist the series be made (even then, the budget was only available because his previous project, the Ben Elton sitcom Happy Families, had its second season cancelled). Set for production in 1987, Red Dwarf then fell foul of the BBC electrician's strike, which delayed filming by almost six months.

"Red Dwarf was a very low-budget affair with limited scope for special effects."

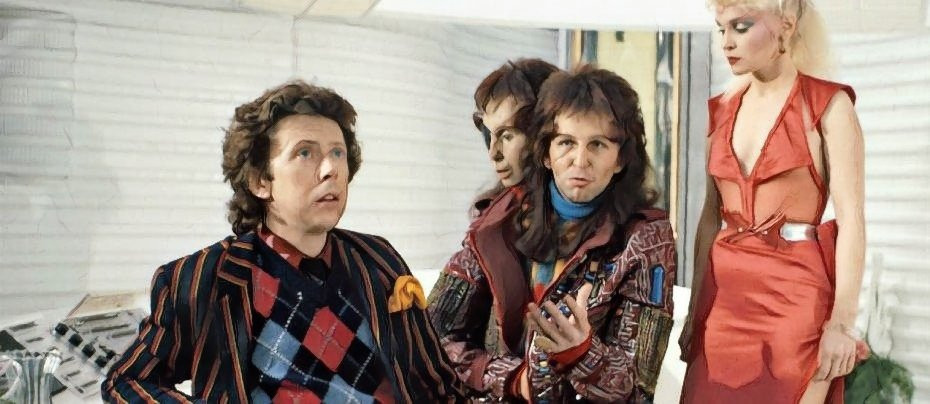

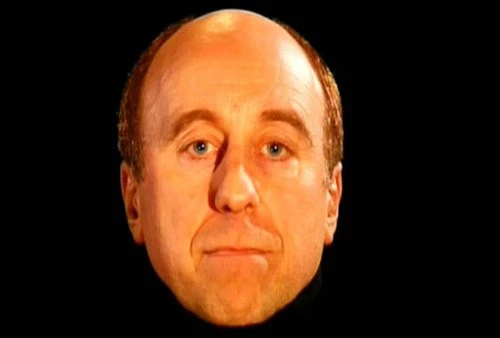

Initial casting was also difficult. Grant and Naylor had their own ideas as to who should play Lister and Rimmer, but approached the casting with very open minds – perhaps too open, considering the difficulty they had in deciding on a final cast. Initially they had hoped to get quite respected actors involved, and both Alan Rickman and Alfred Molina auditioned for the role of Rimmer. Molina was, in fact, cast in the part, but struggled to get tot grips with the concept of the series and the writers decided that he wasn't suited after all. There were flirtations with a female cast – French and Saunders were briefly considered – but eventually they selected a very different cast. First to be cast was Norman Lovett, a deadpan comedian who tried for the role of Rimmer but was eventually cast as Holly. Initially considered a vocal only role, Lovett managed to convince them to make Holly a visual component of the series, although he was still isolated from the rest of the cast, recording against a black screen and appearing as a disembodied head on a monitor. Singer-dancer Danny John-Jules was cast as the Cat. Turning up in an old zoot suit, much of the character of the Cat owed to DJJ's flamboyant audition.

Another performer recommended for the Cat role was Craig Charles, with whom Paul Jackson had worked on Saturday Night Live. After speaking to him about the character of the Cat – concerned that it might be considered a little racist – his enthusiasm for the series led them to casting him in the role of Lister. A stand-up poet (so very eighties), the young Scouser was quite a different person to the middle-aged layabout originally envisioned. The final member of the core four to be cast was Chris Barrie, who initially tried for Lister but was perfect for the uptight Rimmer. Best known at the time as an impressionist, Barrie had collaborated with Grant and Naylor on Spitting Image, Happy Families and Carrott's Lib, and had voiced Hab on “Dave Collins.” Far from the serious actors they had originally hoped for, Grant and Naylor ended up with a comedian, a dancer, an impressionist and a poet, and certainly in the case of the latter three it's now almost impossible to imagine other people in the role. And let's be honest, if Rickman or Molina had taken roles, it's unlikely they would have stayed long enough for the series to become the success it is now.

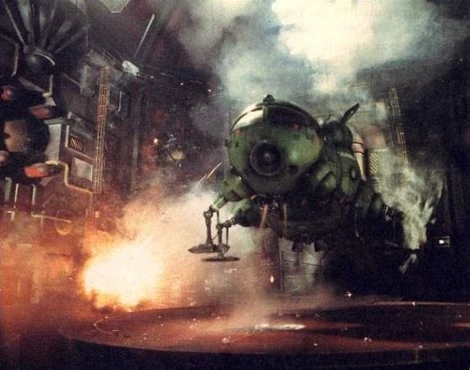

Due to the nature of the storyline, there were limited opportunities for recurring characters. However, the first episode, wittily titled “The End,” featured American actor Mac MacDonald as Captain Hollister, actor and singer Clare Grogan as Kochanski and a then little known actor named Mark Williams as Lister's best friend Olaf Peterson. All three characters were reduced to dust along with the rest of the crew, but were able to reappear several times during the first two seasons via flashbacks and time travel. The first series of Red Dwarf was a very low-budget affair with limited scope for special effects. While model and effects designers created a remarkable visual with the spaceship Red Dwarf – battered and bruised and supposedly six miles long – the interiors of the ship were unimpressive. Set designer Paul Montague was aiming for a submarine feel, but the uniform grey look of the sets and the beige uniforms left many scenes looking dull and lifeless. More memorable was Howard Goodall's score for the series, including the opening theme which strove for a classical science fiction feel, and the more upbeat closing theme song, performed by Jenna Russell, which has remained a staple of the series to this day.

Keen to distance themselves from the hostility towards science fiction, Grant and Naylor pushed the sitcom elements and the series relied on dialogue rather than flashy visuals. Nonetheless, the more popular episodes tended to be the more sci-fi oriented ones, such as “Future Echoes,” in which breaking the light speed barrier caused visions of the future to appear, and “Me2,” in which Rimmer tries to live with a duplicate hologram of himself.

Much was made of the relationship between Rimmer and Lister, with Rimmer revelling in his position as most senior crewman, while Lister preferred to sit around, eating curry and watching cartoons, while the ship slowly made its way back to Earth. “Balance of Power” saw Lister try to outrank Rimmer by passing the chef's exam, while “Confidence and Paranoia” was a high concept piece that saw aspects of Lister's psyche come to life. There was some fun exploration of the Cat's background in the episode “Waiting for God,” which explored Lister's role as the Cat People's holy father, but the poor reception of the episode meant that this was never explored again. Instead, most the Cat's material focused on his feline characteristics – his laziness, selfishness and above all, his extraordinary vanity. Each episode after the first opened with an introduction by Holly, explaining the concept of the series for the benefit of new viewers. The once brilliant AI was revealed to be suffering from computer senility, his three million years of isolation having sent him a bit peculiar.

With a seventh episode slot left vacant at the end of production, the writers took the opportunity to review the first episode and rework elements that they felt didn't come across well. As much as two-thirds of the episode was reshot, with many scenes excised or rewritten. There have been multiple versions of the opening episode released over the years, including the remastered version (from video re-releases in the mid-to-late 1990s), the “original assembly” version and two slightly different Japanese versions with heavily reworked visual effects. Most of these have had DVD releases over the years, although some are now hard to find.

Premiering on the 15th of February, 1988, “The End” performed very respectably indeed, with five million viewers. However, the viewing figures dropped over the course of the first series, in spite of very positive reviews, feedback and a strong Audience Appreciation Index Score. Response was positive enough that the BBC commissioned a second series, which was fast-tracked and began broadcast in September that same year. Continuing along much the same lines as the first series, Series II had a slight budget increase and saw Grant and Naylor experiment more with sci-fi elements. Notably, the first episode introduced several elements that would become staples of later series, including a smaller, shuttle-type spacecraft named Blue Midget, which allowed the Dwarfers to travel to new and more varied locations. It also introduced Kryten, an android, or “mechanoid,” with an amusingly-shaped head, who was built to serve mankind but was left alone for three million years, sending him almost as batty as Holly. Overcoming their reluctance to use a robotic character, Kryten, initially played by David Ross, was popular enough to be brought back for the following series.

The sixth episode of Series II, “Parallel Universe,” was atypical, opening with a musical number (“Tongue Tied,” released some years later as a single by Danny John-Jules, reaching a respectable No.17 in the UK charts), and ending with a cliffhanger in which Lister found himself pregnant by his own female alter ego (don't ask). While the cliffhanger was left mostly unresolved onscreen, the parallel universe concept would be revisited time and again throughout the run of the series, with multiple alternative versions of the characters appearing, not to mention clones, teleporter duplicates and potential future versions. A third series was a given, although there would be big changes in store.

"Red Dwarf III was a huge success."

Red Dwarf III (as it was named in the Radio Times and in the closing line of the series introduction, setting the pattern for how the series would be listed on video and latter-day broadcast releases) both looked and sounded very different to its predecessors. Although the budget had only been increased slightly, more prudent spending made it look like there had been a substantial boost. Mel Bibby completely redesigned the sets (explained internally as a relocation to the officers' area of the ship), which, along with shooting on industrial locations, gave the series a much-needed visual boost. Howard Goodall reworked the opening theme into a new, rocked up version, which played over a montage of scenes from the upcoming episodes, a technique which has continued on every series to this day.

A very, very fast Star Wars-styled opening crawl brought audiences up-to-date (but only if they recorded it and played it back in slo-mo), hurriedly explaining the events between series II and III. While Charles, Barrie and John-Jules were all back, Norman Lovett had grown weary of the commute from Edinburgh and had declined to return to the programme. Instead, the showrunners cast Hattie Hayridge as a new version of Holly, after she had played Hilly, the character's parallel universe equivalent in the previous episode. Hayridge would portray the ditzy blonde version of the computer for three series. The other new addition to the cast was Robert Llewellyn, the recast and redesigned Kryten. Over the course of the first two series, it had become clear that a new character would be useful in facilitating storylines, given that Lister and the Cat were disinclined to do work, and Rimmer, as a hologram, was unable to touch anything. Other changes included removing Holly's introduction, giving Rimmer free reign off the ship (explained in the following series by the introduction of a small, portable “light bee,”) and a brand new shuttle, Starbug, which replaced the rather poky and ugly Blue Midget.

Red Dwarf III was a huge success, and secured the direction of the series for the next few years. Episodes such as the opener, “Backwards,” the two-hander “Marooned” and the sci-fi monster fest “Polymorph” are considered absolute classics by fans. The series had by now started to develop its cult following, and had begun to be exported to Europe and the USA. 1989 also saw the writers publish their first novel, under the combined pseudonym Grant Naylor (later the name of their production company). Red Dwarf – Infinity Welcomes Careful Drivers was the definitive take on the concept, giving considerable space to Lister's backstory before adapting several popular episodes. It followed in 1990 with Better Than Life, very loosely based on the Series II episode of the same name. Red Dwarf IV was broadcast from Valentines Day in 1991. This incorporated some elements from the novels, for example changes to Lister's backstory – the writers considered Lister's unrequited pining for Kochanski rather puerile and rewrote history so that the two had enjoyed a whirlwind affair. A move from Manchester to Shepperton Studios also gave them access to more industrial location filming, cementing the look for the series. Otherwise, Series IV continued with the same winning formula as Series III. It's most notable episode, “Dimension Jump,” introduced another parallel version of a regular character – Ace Rimmer, the heroic counterpart to Chris Barrie's usual character.

The following year saw Red Dwarf V continue the series' most successful period, and is considered by fans and critics as among the best, if not the best, years in the programme's run. Having relied mostly on sitcom-style character interaction in its earliest years, the series now shifted very heavily towards sci-fi adventure, albeit still as a comedy first and foremost. Series V featured such favourites as the Rimmer-in-love episode, “Holoship,” the existential threat of “The Inquisitor” and the outright ludicrous “Quarantine,” which saw Chris Barrie go for broke as an insane Rimmer in a gingham dress (and army boots). Barrie was fast becoming the star of the show, with more and more episodes revolving primarily around him, although Lister, Kryten and the Cat remained hugely popular. Holly, on the other hand, was becoming increasingly sidelined, with Kryten as the brains of the operation. The Series V finale, “Better Than Life,” is consistently rated as one of the very best in fan polls. It features a common sci-fi trope – the main characters waking up to find their lives are a fantasy or virtual construction – but with Red Dwarf you could actually believe they might go through with it and rewrite the whole of the series' past. (The fact that a sixth series was uncertain helped sell this even further). Although normality (such as it is) was restored at the episode's end, “Better Than Life” had a huge influence on certain later episodes, and introduced yet another recurrent character – the Cat's geeky alter ego, Duane Dibley.

There was a reasonable gap between the end of Series V in March 1992 and the premiere of Series VI in October 1993. This was primarily down to Grant Naylor Productions exploring new avenues and projects, but the intention to produce a sixth series was always there, especially as American distribution was increasing. With this in mind, the writers touted the series for an American studio remake. Both Llewellyn and Barrie were approached by the Universal and NBC to reprise their roles in the States, although only Llewellyn took them up on the offer. The remaining parts were recast for a pilot episode (simply titled Red Dwarf, although commonly referred to as Red Dwarf USA). With the original creators onboard as executive producers, it was written in a clearly American style by Linwood Boomer (later creator of Malcolm in the Middle) and lacked the appeal or easy style of the original, although there were some good gags. A second pilot with a mostly new cast was more of a show reel, with several classic scenes from the original remade with new actors. Neither pilot was considered successful enough to spawn a new series, and the writers returned to the UK to work on Series VI.

Filmed in time for a spring release, BBC2 decided to hold it back for the autumn in order to maximise the potential audience. Grant and Naylor took the opportunity to rework the series considerably. Red Dwarf VI was the first series to not feature the eponymous spaceship at all, and was instead set entirely on Starbug. The gap between series was utilised onscreen as well, with an in-story lapse of two centuries occurring between when we last saw the Dwarfers and when Lister was pulled out of suspended animation in Series VI. At the BBC's request, the first episode was styled as a reintroduction, with Lister's post-sleep amnesia giving Kryten an excuse to explain the new set-up to the audience. Now on the trail of the stolen Red Dwarf, confined to the shuttle and with no Holly, the series was made more of a survivalist adventure, with a monster/villain-of-the-week format. Starbug's interior sets were substantially increased and redesigned to make it a suitable setting for the series, while the model work, by veteran effects artist Mike Tucker and crew, was exemplary. Video effects were also improved, making the series visually impressive. In terms of writing, Grant and Naylor put more emphasis on repetitive gags such as Rimmer's obsession with Space Corps Directives and almost Blackadder-esque absurd similes, which was all intended to make the series more palatable to an American style of humour. In spite of the survivalist angle, the characters were made more self-sufficient, with the Cat developing superhuman abilities of smell, while Rimmer was upgraded to “hard-light” in the second episode, allowing him to touch things at long last.

Red Dwarf VI was another big success, although some fans and critics were less pleased with the new style. Nonetheless, it includes some hugely well-regarded episodes, such as the wonderfully strange “Legion,” which includes perhaps the best line in the entire series (the one with the red alert bulb), the Emmy Award-winning western “Gunmen of the Apocalypse” and the Chris Barrie showcase “Rimmerworld.” The series ended with one of Red Dwarf's many time travel-based episodes, “Out of Time,” which saw the Dwarfers fight to the death against their own future selves. Hopeful of a seventh series, Grant and Naylor gave the episode a last-minute rewrite, leaving it on a tantalising cliffhanger, one that wouldn't be resolved for over three years.

More events behind the scenes delayed production of the seventh series. Rob Grant and Doug Naylor decided to dissolve their writing partnership in order to focus on their own projects. They were together contracted for two more Red Dwarf novels, and elected to write one each, both continuing separately from the end of Better Than Life. Of the two, Naylor's 1995 novel Last Human bore the least resemblance to the series, although elements later came to play onscreen, while Grant's 1996 release Backwards was a particular success, adapting elements from some of the most popular episodes. Chris Barrie had found significant success in the title role of the BBC1 sitcom The Brittas Empire since 1991, and had less interest in or time for Red Dwarf. More seriously, Craig Charles was arrested and remanded in custody on an entirely unfounded rape charge in 1994, and was not released until early 1995. All these events made a new series of Red Dwarf unlikely. In the meantime, BBC2 ran a full run of repeats, the first time that Series I was broadcast since its initial showing.

Red Dwarf VII (numbered onscreen at last, although this time not in the Radio Times listing) finally arrived in January 1997. Advances in CGI and a bigger budget than ever before led to more impressive visuals than could previously be achieved, and for the first time the series was filmed in a closed studio instead of in front of the traditional live audience. Grant declined to return, and has kept his distance from the series since. Instead, Naylor took over as head writer and showrunner, with additional script work from Paul Alexander on several episodes, plus one-off contributions from Kim Fuller, James Hendrie and Robert Llewellyn (the Kryten heavy “Beyond a Joke”). After six series of six episodes, the count was bumped up to eight, on the basis that two series of that length would bring the overall count to fifty-two, enough for American syndication. The most obvious changes for the audience were in the cast. Committed to filming the fifth (and, it turned out, final) series of Brittas, Chris Barrie could not appear in every episode, instead signing up for only half. In the event, he was written out in the second episode, “Stoke Me a Clipper,” which saw Rimmer become his heroic counterpart Ace, but appeared in flashback in two further instalments.

To replace him, Naylor went back to the series routes and brought back Lister's one true love, Kristine Kochanski. Having included her as a main character in Last Human, Naylor felt that a female presence made for a more well-rounded cast. It certainly made for a very different dynamic for the series. Instead of bringing Clare Grogan back, Naylor cast Chloe Annett, a much posher and far less Scottish version of the character, from yet another parallel universe. Stranded on Starbug with an attention-starved Lister, a jealous Kryten and a randy Cat, Kochanski was not best pleased with her lot. Fans and critics alike were divided on Series VII, but the more complex and dramatic storylines led to some strong episodes, particularly the ingenious series opener “Tikka to Ride.” It did particularly well on video, with three of the episodes being released as special extended editions featuring previously excised scenes and souped up effects. Far better than is often remembered, Red Dwarf VII is nonetheless far from the series in its prime – perhaps better science fiction than comedy.

"The BBC declined to renew Red Dwarf for a ninth season."

Series VIII would provide further changes, some of which were signposted in the final Series VII episode, “Nanarchy.” This episode saw the mothership return, having been miniaturised by microscopic robots and left to explore strange new worlds in Lister's laundry basket for the last few centuries. Exploring the excess matter left on a desolate planetoid, the Dwarfers found Holly – rebooted back to his original Norman Lovett self, although somehow even more senile than before. The final shot of the seventh series saw Red Dwarf returned to its original state – more or less. Red Dwarf VIII – subtitled “The Tank,” on paper at least – arrived in 1999 and saw massive changes. The nanites had not only restored the ship, but the crew as well, reconstituted from their irradiated remains. Chris Barrie returned full-time as Rimmer, alive once more, along with Mac MacDonald as Hollister, reappearing for the first time in over ten years and promoted to regular. Mark Williams, on the other hand, declined to return as Peterson, having since achieved huge success on series such as The Fast Show.

With the largest core cast of any version of Red Dwarf, and a complete crew complement allowing for multiple guest and recurring characters, Series VIII was a world away from the isolation of the series' beginnings. In other ways, though, it was a return to first principles. Once again in filmed in front of a live audience, the episodes were more in the style of traditional sitcoms, although there were plenty of sci-fi elements. The main characters were imprisoned in the eponymous Tank, a hidden gaol in the belly of Red Dwarf, for stealing Starbug and other misdemeanours. While this was a big change of scene, it also put the characters in reduced circumstances once again, with Lister and Rimmer's cell becoming the equivalent of their confined quarters in the earliest episodes. Although numerous elements from the past were reintroduced, visually it was a world away from Series I and II, with the heavy CGI usage and redesigned ships from the remastered video releases. The uniforms were still beige though.

In spite of what were expected to be fan-pleasing elements, Red Dwarf VIII was quite poorly received. The humour was broad and often obvious, and there were some poor performances by some of the recurring cast. The expanded core cast was difficult to handle; Kochanski in particular worked poorly in the new set-up. Although it was wonderful to have Holly back, he was surplus to requirements and was woefully underused. A stretched budget also led to storylines being stretched across several episodes, so jokes often wore thin. Nonetheless, the fourth episode, “Cassandra,” is a minor classic, a high concept episode that calls back to the style of Series V. The series ended on another huge cliffhanger, with the crew once more facing certain death.

The BBC declined to renew Red Dwarf for a ninth season – perhaps unsurprising considering the fairly poor reception. Nonetheless, the series was still popular worldwide, spurring Naylor into pursuing a movie option. A script was written by 2001 and movement on the project went in fits and starts, but by 2005 it appeared to be well and truly dead. One problem might have been that both Naylor and the fans were insistent on keeping the original cast, none of whom were big names internationally and who were not getting any younger. In the event, some material from the film script was reused for the Series X finale some years later, but nothing more has come of the project. Instead, BBC Worldwide made overtures to bring the series back for a twentieth anniversary special in 2008. This, too, went through different permutations, eventually being picked up by channel Dave, which up to that point had relied mostly on repeats for its programming. Red Dwarf continued to be one of its most popular programmes – there is a persistent rumour that the channel is named after Lister – and new Red Dwarf provided a perfect opportunity for fresh programming. Initial talks suggested an hour-long special, a making-of programme and the intriguing sounding Red Dwarf: Unplugged, an improvisational format. In the event, a three-part special was made, entitled Red Dwarf: Back to Earth.

Back to Earth was not what fans expected. Broadcast in 2009, and set an equivalent amount of time after Series VIII, the serial maximised its near-anniversary position by incorporating many callbacks to the past, but was quite unlike any previous Red Dwarf story. The cliffhanger to the previous run remained unresolved (something even the characters joke about in later series), and instead we joined the core cast of Lister, Rimmer, Kryten and the Cat onboard the once more abandoned and dilapidated Red Dwarf. Holly and Kochanski are no longer included – the latter missing presumed dead, the former offline following a flooding incident after Lister left a tap on for four years. Rimmer is once more a hologram, although it remains unclear as to which version of Rimmer this is. Although it represented a return to the most popular group of core characters, the serial otherwise changed things up considerably. A new hologram named Katerina, played by Peep Show's Sophie Winkleman, guest starred, and the entire cast of characters returned through a rift in spacetime to Earth, in the 21st century. What followed was a fourth wall-breaking escapade that saw the characters discover that they were fictional creations on a television show, and spend a considerable amount of time on the set of Coronation Street (Craig Charles having a regular role on the soap from 2005 to 2015). The final instalment was a sustained parody of one of Grant and Naylor's main influences, the 1982 classic Blade Runner.

Although the cast slipped effortlessly back into their onscreen personas – perhaps even better than before, having honed their acting talents over the intervening years – Back to Earth was disappointing. Often seeming derivative and lazily written, it was a pale shadow of the beloved series. It was not without its moments, of course, although the funniest joke was perhaps at its own expense, with characters from the “real world” commenting that the nonexistent Series IX was the best Red Dwarf had ever been. In spite of some strong character moments for Lister, the plot never gelled, and the revelation that it was all a sequel to “Back to Reality” only served to remind viewers how good the series was in its prime.

Still, it had been popular and well-promoted enough to gather a decent audience of two million for the first episode, although this halved for episodes two and three. Nonetheless, these represented excellent figures for a digital-only channel and Dave were quick to express interest in a full series of Red Dwarf. Reverting to the numbered format, Red Dwarf X appeared in 2012, and saw Naylor regain much of the series' successful balance between humour and plot. Something of a return to the classic days of the series, the new episodes were once more filmed in front of a studio audience, an approach that both cast and fans prefer. Rather than the serial plot of Back to Earth, Series X returned to the format of six standalone episodes, although there were elements that carried on throughout the series. Wisely, Naylor chose not to ignore the ageing of the cast, but instead to embrace it, poking fun at the idea of a bunch of middle-aged men in space. Still winding each other up, the characters are more at peace with each other after their many years together, although Rimmer still has an uncanny knack for being an unbearable jobsworth. Initial plans for the series would have led to Kochanski being found alive and well, somewhere in deep space, but the usual problems of limited budget and cast availability led to this subplot being nixed late in the day. This is perhaps for the best; the series works best when it is confined to the core group of characters.

Series X gained some of the highest audience figures for Dave, with critics and fans noting that it recaptured some of the feel of the earliest episodes while embracing the sci-fi shenanigans of the popular fourth and fifth series. Mike Tucker and crew utilised both model work and CGI for a well-rounded visual approach that made the episodes look more expensive than they really were, and Howard Goodall used early series music cues to evoke the classic episodes. All in all, Series X was enough of a success to ensure plans for a further two series. After initial discussion had been finalised, Craig Charles quit Coronation Street and all were available to film a full twelve episode run in late 2015 to early 2016. This budget-conscious approach of filming two series back-to-back worked well, although keeping a lid on plot developments proved challenging (Steve Coogan's Baby Cow Productions also joined as co-production company, which must have helped financially). Both Series XI and XII built on the success of Series X, with the writing improving further and really capturing much of the original run's successful formula. Red Dwarf XI was broadcast in 2016, with the twelfth following a year later. The 73rd and to date final episode of Red Dwarf, “Skipper,” served as something of an early thirtieth anniversary celebration, homaging several classic episodes and bringing back Norman Lovett and Mac MacDonald for one last hurrah.

With Naylor and all four main cast members keen to keep producing the series, it seems likely that Red Dwarf XIII will one day see the light, although current plans are apparently for an arena-sized live show. Whatever form it takes, the latest episodes have shown that when it sticks closely to its roots it still has what it takes to be a big hit. Over thirty years (or three million, depending on your point of view) Red Dwarf has cemented its position as the world's most beloved sci-fi comedy series. Smegging fantastic.

Published on February 19th, 2019. Written by Dan Tessier (February 2018) for Television Heaven.