Life, The Universe...

...and Pretty Much Everything About the Hitch-Hikers Guide

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has manifested itself in many forms over the years. For some, the definitive version is the original radio series, which began in 1978. For others, the book series which began in 1979 is the best iteration of the story. Some fans, though, will point to the 1981 television series as their favourite version of the legendary sci-fi comedy.

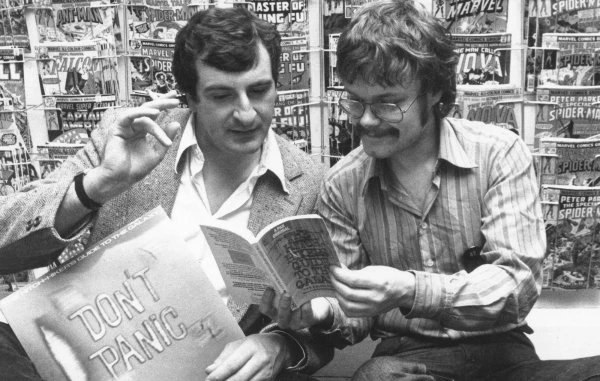

The history of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is long and storied, but to be brief, Douglas Adams turned an idea he had whilst bumming around Europe into the basis of a science fiction comedy series for BBC Radio 4. The premise was as bizarre as it was ingenious: just as his home is being demolished to make way for a bypass, ordinary human being Arthur Dent is pulled from his life by his friend Ford Prefect, who turns out to be from a small planet somewhere in the vicinity of Betelgeuse, and not from Guildford as he'd previously claimed. Escaping before the Earth is itself demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass, Arthur and Ford drift through the universe on a series of adventures that make it clear the rest of the universe is just as bureaucratically nightmarish as the Earth.

In spite of the first episode being broadcast in a graveyard slot, it received an astonishing audience reaction, and the first series of six episodes was rapidly followed by a second. It was while working on the second series during 1979 that Adams was commissioned to write the scripts for a television version. Many considered the series unfilmable, featuring as it did fleets of spaceships, a two-headed alien and people turning into penguins. While there was some talk of making the series animated, it was eventually decided that only the sequences representing the Hitchhiker's Guide itself would be. John Lloyd, who had worked on the radio scripts with Adams, took charge of the adaptation process early on to allow Adams some respite. Nonetheless, given that he was working on the second radio series at the time, along with a position as script editor for Doctor Who, it was decided to delay production of the TV version for the better part of a year. (Adams’ unique honour of being the only person to write for both Doctor Who and Monty Python's Flying Circus, and Hitchhiker's is about as close to a cross between those three series as you can get.)

Adams delivered the finished script for the first episode in December '79, with terms agreed for the remaining five episodes agreed shortly after. Production began on the pilot early in 1980. Rod Lloyds of Pearce Animation Studios provided the animation for the Guide sequences. The colourful line art gave a futuristic but humorous look to the Guide. While it looks distinctly un-futuristic now, it's also nothing like any recognisable graphic systems, giving the Guide a timeless feel that has helped keep the series from ageing poorly. As in the radio series, the voice of the Guide was provided by Peter Jones (best known at the time as Mr Fenner on the sitcom The Rag Trade, which had finished its second television run around the time Hitchhiker's began on the radio). His gentle, rather posh intonation provided a reassuring narration to the madcap events, just right for a book with the words "Don't Panic" emblazoned on its cover.

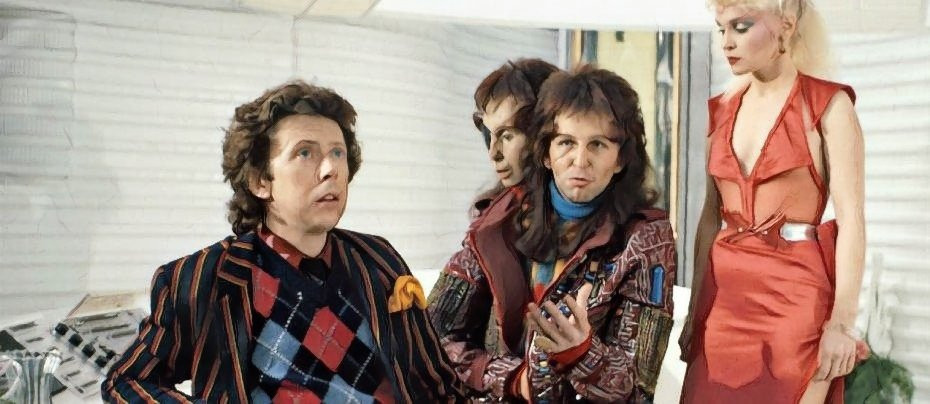

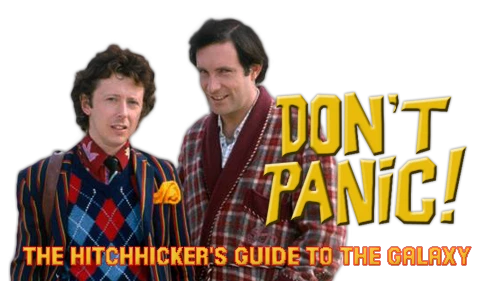

Also returning from the radio series were Simon Jones as Arthur and Mark Wing-Davey as alien layabout and President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox. Adams had written the part of Arthur specifically for Simon Jones. This was only early in his career, with notable roles in Blackadder II, Brideshead Revisited and Tattinger's still to come. However, in spite of being only about thirty when recording the TV pilot, Jones still possessed a certain middle-aged weariness; the quintessential exasperated Englishman. Wing-Davey had been picked for the role of Zaphod based on his louche performance in 1976 series The Glittering Prizes. While not required for the pilot, his inclusion for the full series was assured. However, his character's possession of a second head – a throwaway joke on radio, a nightmare for television – proved very difficult to realise. His third arm wasn't such a problem, merely inert unless required to move, when another person would hide behind Wing-Davey and stick his arm through the jacket. The head, though, was eventually realised by way of some very primitive animatronics. It's probably the biggest flaw with the effects of the series and taking the stage play's solution of having two actors share a costume would probably have worked better.

The other two main cast members were recast for television. It was decided that Geoffrey McGivern didn't suit Ford Prefect visually, and so he was replaced by David Dixon (A Family Affair, The Legend of Robin Hood). Dixon's version of the Guide researcher had an air of the perpetual student about him, in a mismatched outfit that wouldn't have looked out of place on an incarnation of Doctor Who. Appearing from the second episode, along with Zaphod, was Trillian, nee Tricia MacMillan, the other survivor of the human race, who had luckily skipped the planet some months earlier on a whim. Susan Sheridan was anticipated as returning to the role on television, but was unavailable at the time. As such, Trillian was recast, played now by Sandra Dickinson. Early in her career herself, the Anglo-American actress had already become somewhat typecast as a "dumb blonde" type, due to her high-pitched ditzy-sounding voice as well as her appearance. She was quite an odd choice for the highly intelligent, very English Trillian, but made the part her own. Dickinson wouldn't play Trillian again until the revived radio series reached its fifth (or "Quintessential") phase in 2005, in which she played Trillian's Americanised parallel universe counterpart.

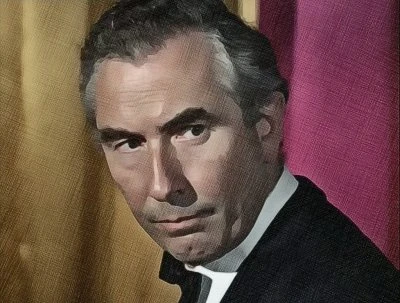

The rest of the cast includes some exceptional performances, as well as some surprising cameos. Stephen Moore reprises the role of Marvin the Paranoid Android (or more accurately, the clinically depressed android), having been cast on the radio version partly for his equally morose turn as Jack on musical drama Rock Follies. Still a voice role for Moore, Marvin was realised on screen as a charmingly retro-looking silver robot, worn as a bulky costume by David Learner. David Tate returns as the irritatingly chirpy ship's computer, Eddie. Sword of Freedom star and prolific cinematic character actor Martin Benson portrayed Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz, captain of the demolition fleet, underneath a mountain of latex and green make-up. Richard Vernon, who had been cast in middle-aged to elderly roles since his thirties, reprised his role as the wonderfully named Slartibartfast, last of the Magratheans.

‘The Man in Black’ himself, recently the Black Guardian on Doctor Who, Valentine Dyall provided the imposingly booming tones of Deep Thought, the second-most advanced computer in the history of the Galaxy. At the Restaurant at the End of the Universe, the Dish of the Day – a pig-like food animal desperate to be eaten – was played by none other than Peter Davison, shortly to take the lead on Doctor Who. While the original actor cast in the role has been hard to verify, we do know he was recast due to difficulties in recording, with Davison – then husband to Sandra Dickinson – drafted in at the last minute. Notable film actor Aubrey Morris (A Clockwork Orange, The Wicker Man) played the affable but ultimately useless Golgafrinchan Captain ("One's never alone with a rubber duck"). As common in radio production, many of the bit-part voices were provided by actors from the main cast. Also of note are several cameos by Adams himself, both in person and as illustrations for the Guide.

The television version runs along more-or-less the same lines as the first radio series, albeit with some jokes tweaked or given to different characters. It's clear that Adams took the opportunity to refine some of his material. Arthur and Ford are picked up by random chance by the starship Heart of Gold, thanks to its experimental Infinite Improbability Drive, which has been stolen by Zaphod and Trillian. All this is part of Zaphod's personal mission to find the legendary planet Magrathea, which was once the centre of an industry dedicated to manufacturing bespoke planets. They discover that the Earth was created by the Magratheans to act as the ultimate computer, to find the Question that matches the Answer to Life, the Universe and Everything (which, as we all know, is forty-two).

However, the fifth and sixth episodes, co-written for radio by Lloyd, were heavily altered. While both fifth episodes feature the characters arriving at the Restaurant at the End of the Universe and stealing the spaceship of deceased (for tax reasons) galactic rockstar Hotblack Desiato, much of the material is wholly reworked and the ending entirely rewritten. By this stage, Lloyd's involvement was largely over and his material mostly excised, although he did still receive a credit. Episode six cuts out a lengthy (and not particularly successful) sequence involving shapeshifting aliens, and moves the plot straight to the B-Ark of the Golgafrinchams, who proceed to crash-land on prehistoric Earth. Nonetheless, both versions end with an uplifting playing of Louis Armstrong's "What a Wonderful World."

These alterations did not originate with the TV series, but were worked in by Adams for the LP recording and stage play script, but these were of limited audience, and this was the first time the new version truly overwrote the radio original. This new version is also more in-line with the version of events presented in the first two novels, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. They've very much become the definitive version of events for all but radio purists.

For all its limited budget, and Zaphod's extra head notwithstanding, the series looks wonderful. It's clearly rather cheap but the creativity involved is remarkable, with all manner of peculiar beings appearing throughout. Particularly impressive is the model work, with the Heart of Gold, the Vogon Destructor Ship and the B Ark all vividly realised. The series also has a wonderful sound, from the strange otherworldly noises and radiophonic music provided by Paddy Kingsland (who was also working on Doctor Who during this period, leading to a certain similarity in the audioscape of the two series). And of course, the Hitchhiker's theme tune, "Journey of the Sorceror" began every episode, here in a new arrangement by Tim Souster. Written by Bernie Leadon for The Eagles, the instrumental piece was originally chosen for the radio series by Adams because it combined an ethereal, alien sound with the folk sound of the banjo.

The series was a success, bringing in respectable viewing figures, no doubt buoyed on by the existing popularity of the radio series and novels. A second series was planned, but ultimately never came to pass. The exact details are unknown, with conflicting accounts from different people, but in any case, there was a dispute of some kind between Adams and the BBC. It's unknown whether the second series would have taken any material from the second radio series, although it seems unlikely, they would have had much in common, as most of this material was jettisoned for the novel range. The director of the series, Alan Bell, as well as Wing-Davey, have stated that Adams had begun reworking material from his proposed Doctor Who film treatment, Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen. This story was eventually adapted to become the third novel, Life, the Universe and Everything. In the next century, this would in itself be adapted to become the third radio series, and finally, a novelisation was written to bring a version of the original Doctor Who story to life.

While the second TV series never materialised, this wasn't the last time the Guide would make it to the screen. In late 2003, the BBC recreated several scenes from the novels as part of The Big Read, with Sanjeev Bhaskar (Goodness Gracious Me) as Arthur, Spencer Brown (Garth Marenghi's Darkplace) as Ford, and Nigel Planer (The Young Ones) as Marvin. Of particular interest in terms of casting was astronomer Patrick Moore as the Guide, and theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking as Deep Thought. In 2005, after years of failed attempts to get it on the big screen, a film version was released, starring Martin Freeman (Sherlock, Fargo) as Arthur and rapper Mos Def as Ford. In this version, the ubiquitous Stephen Fry voiced the Guide and Alan Rickman voiced Marvin, while Helen Mirren was Deep Thought.

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy will return to television next year for streaming on Hulu, although casting details have yet to be released. Sadly, Adams did not live to see any of these versions, having died in 2001, aged only forty-nine.

Published on December 5th, 2022. Written by Daniel Tessier for Television Heaven.