Sherlock

2010 - United KingdomThe story goes that the idea originated on a train journey to Cardiff, where Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat were working on Doctor Who for BBC Wales. Like so many great ideas, its brilliance came from its simplicity: why not update Sherlock Holmes by putting him in a contemporary setting?

Like so many great ideas, it was also not particularly original. It had in fact been done before, most memorably in the later features of the definitive film series with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce which were set during the Second World War.

Cinephile Gatiss - who also fronted an excellent documentary on portrayals of Holmes which gave the impression that he really knows the subject - was well aware of this. What differentiated him and Moffat from the mass of other writers who have had similar ideas was that they had the contacts at the BBC to get it made.

It was certainly an idea whose time had come. This was confirmed by the fact that it was soon followed by an American show with the same basic concept, Elementary. However, the British version came first and it hit the ground running. Holmes became a metropolitan trendy addicted to texting. Computer graphics illustrated his mind at work. Watson describes his adventures in a "blog" rather than articles for a magazine. With Cardiff, again, standing in for London, the whole thing was slick and well-paced and an instant hit.

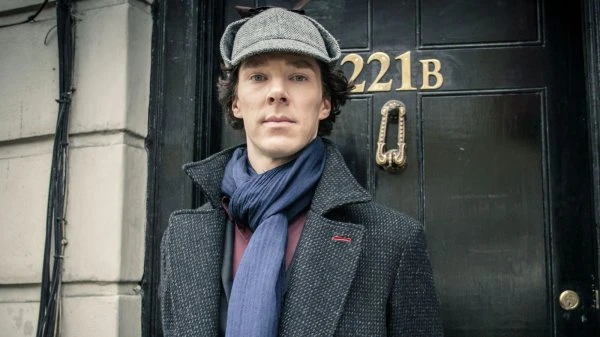

Two factors explain its success. The first and most important was the casting. The fact that both Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman have since gone on to astonishing success on both sides of the Atlantic proves that the producers had an eye for talent. While Sherlock cannot be described as their breakthrough, since both already had well established careers and full curricula vitae, it was the store that really set out their wares to the world.

Giving Holmes a self-perception that would have been alien to the Conan Doyle original, Cumberbatch plays him as a "high functioning sociopath." Whether this is an accurate analysis or an attempt at disguising his vulnerability is left nicely ambiguous. Either way, he is egotistical, almost deliberately arrogant, and often rather unpleasant. Despite that, people loved him. His Byronesque combination of intellect with his "bad boy" image made him a bigger hit with women than any previous Holmes.

Watson is in many ways the more difficult role. Although Conan Doyle made it clear that he was far from an idiot, it is a tribute to Nigel Bruce that his portly frame casts a giant shadow. Freeman gives us a more intelligent Doctor, even if at times he seems more like Holmes' resident carer than his friend and associate. One cannot help thinking of the tongue-in-cheek American detective series Monk with Tony Shalhoub.

By an accident of history, Freeman's Watson, like his Victorian counterpart, served in Afghanistan - which brings us to the second reason for the show's success, the wit with which Gatiss and Moffat brought the original stories into the 21st Century. So the Six Napoleons became the Six Thatchers, the Hound of the Baskervilles was the effect of an hallucinogenic gas, and Irene Adler became a dominatrix.

This had the effect of keeping more traditionalist Holmes fans happy, playing "spot the reference," while at the same time introducing a younger audience to the stories.

The show went into decline because it failed to maintain that balance. As with Doctor Who, more traditional viewers were put off by the way Gatiss and Moffat kept on about their own obsessions and opinions. Baker Steet became a BBC "echo chamber." At the same time, the show developed into more of an action orientated conspiracy thriller than a detective mystery.

Both of these failings are summed up in the treatment of Watson's wife, Mary. Any realistic updating of Conan Doyle in the 21st Century was bound to bring her out of the shadows - it is a plain fact that the role of women in Britain has changed radically in recent years and the series was right to reflect that - but that she just happened to be a highly trained killer was simply ridiculous.

In the same way, one of the great initial strengths of the show was turned into a great weakness. Gatiss is a professed admirer of Billy Wilder's delicious feature The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and in particular of Wilder's clever conceit of turning Sherlock's more intelligent brother, Mycroft - a perfectly cast Christopher Lee in the film - into a secretly powerful adviser to the British Government.

Gatiss copied that idea and had himself cast as Mycroft. At first, both of these decisions proved to the show's advantage. However, Gatiss the Writer did Gatiss the Actor too many favours, so that what had been a nice touch began to dominate the plot. The focus went from two friends in Baker Street solving crimes to grand conspiracies involving the power of the State.

What worked well in the brisk Wilder film was flogged to death in the television series - not least because the British Government is not as significant as it was during the Victorian Empire and, frankly and meaning no disrespect, because Mark Gatiss, for all his many undoubted talents, is no Christopher Lee.

While it would be easy to write Sherlock off as yet another on the very long list of high concepts that never lived up to their early potential, it may be too early for obituaries. It is certainly true that the show is no longer in production, and Cumberbatch and Freeman are likely to be busy earning more serious money for some time. However, if there is one thing we have learnt about Holmes - ever since Conan Doyle chucked him off Reichenbach Falls so that he could concentrate on his more serious work - it is that we should never assume that he is dead.

It is therefore by no means impossible that Sherlock might return one day, and if Gatiss and Moffat use the intervening period to reflect on the reasons for the success and the failure of the show, it might once again be as compelling as when it burst on to our screens almost a decade ago.

Review - John Winterson Richards

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 29th, 2019. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.