The Greatest Show in the Galaxy

The fourth and final serial of Doctor Who's twenty-fifth season, The Greatest Show in the Galaxy represents a sudden upsurge in the quality of the programme. While there had certainly been some entertaining and inventive material in the preceding few years, much of it worthy of comment, the overall level of quality in the series had taken a fall. Andrew Cartmel, taking on the role of script editor and story commissioner for the programme in 1987 in the twenty-fourth season, recruited new, younger writers, who had watched the series as children but, vitally, weren't hardcore fans. They brought with them new takes on the programme, based on memories of what it had been like to watch it as children, combined with modern, media-savvy ideas.

The twenty-fifth season in 1988 saw this pay dividends. While there were only four stories per season in this period, three of them in this year were genuinely clever, exciting and fun. The season began with the rollicking, nostalgic Remembrance of the Daleks, and continued with the political and allegorical The Happiness Patrol. Only Silver Nemesis, unfortunately, pegged as the official twenty-fifth-anniversary story, fell substantially below par. The season finished with The Greatest Show: a love letter to the series' past, a cheeky mockery of fandom, an analysis of the corruption of sixties ideals, and a prescient look at the direction television would take in the next few decades.

1985's Vengeance on Varos had been one of the strongest stories of the twenty-second season, with a foresighted look at the concept of reality television, taken to its most gruesome extreme. The Greatest Show takes on a related concept: that of the talent contest. Stephen Wyatt, a promising young writer who had caught Cartmel's eye with Claws, a BBC drama about infighting and backstabbing amidst a cat show, first wrote for Doctor Who with Paradise Towers, a clever if flawed 1987 serial. He returned for the following season with this, a story set in a space circus. All the location work had been completed in a quarry in Dorset (a Doctor Who standard, of course), but just before studio work was due to start, the whole of Television Centre was shut down due to the presence of asbestos. In one of those serendipitous moments that sometimes arise from a crisis, this was the one serial where a ready-made solution presented itself: they hired a big top tent and put it up in the BBC car park. This had the effect of making all the circus scenes look far more effective than they would likely have done in the studio.

In the serial, the Doctor (Sylvester McCoy) and his companion Ace (Sophie Aldred) receive some robotic junk mail aboard the TARDIS, challenging them to enter themselves as acts at the Psychic Circus. Ace, who is (allegedly) only seventeen or so, is egged on by the robot and decides they should enter to prove she's not scared. (Given how the TARDIS is supposed to be virtually impenetrable when in flight, how the Doctor later states he knows the villains of the story of old and how generally manipulative this version of him is known to be, it certainly looks like he set the whole thing up.) They arrive on the desolate planet Segonax, sometime in the far-off future, and slowly make their way across the plains to the Circus.

The Psychic Circus itself is presented as a legendary troupe, having toured the galaxy for years before eventually getting stuck on Segonax. Things definitely don't seem right at the Circus anymore. Two of the performers, Bellboy (Christopher Guard – I, Claudius; Return to Treasure Island, Les Misérables) and Flower Child (Dee Sadler – No Place Like Home) are on the run from a chorus of sinister clowns (is there any other kind?) Morgana (Deborah Manship – Angels), affecting a Gypsy persona, runs front of house, while the Ringmaster (Ricco Ross, one of the very few American actors in the original Doctor Who), sings an awkward and cringeworthy rap each time he introduces a new act.

There's Deadbeat, a sullen, half-crazed character who quietly sweeps the floors and mutters to himself. He is played by Chris Jury, who had actually auditioned for the role of the Doctor when McCoy did but is best known as loveable nitwit Eric in Lovejoy. Finally, there's the Chief Clown. Played by Ian Reddington, best known for his soap work (he was Tricky Dicky on EastEnders in the nineties and Vernon on Coronation Street in the noughties), the Chief Clown is one of the most unsettling villains in the latter years of the series. Commanding the army of clowns (robotic, in their case) that track down runaways, he'd be creepy enough just for his crooked smile and death-white face, but it's Reddington's performance that makes him stand out.

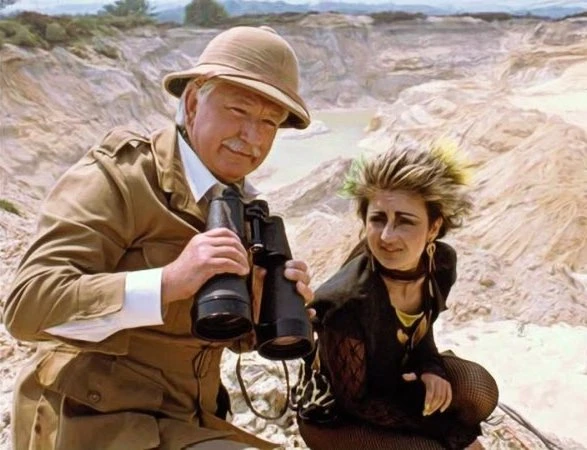

The Circus itself is virtually unattended, save for a handful of misfits who have made their way across Segonax to perform, and a small family of three in the audience, dispassionately watching the events. The Doctor and Ace meet a number of these strange characters along the way, along with a sole native inhabitant of the planet, a fruit stall proprietor played by the incomparable, perpetually middle-aged Peggy Mount (George and the Dragon, The Larkins, John Browne's Body). Most important to the plot are the intergalactic explorer Captain Cook and his ward/specimen Mags, a parodic reflection of the Doctor and his ongoing roster of companions. The Captain, who drones on with endless anecdotes of this planet and that galaxy, is played with stuffy, old-fashioned imperialism by T. P. McKenna (Crown Court, Callan, Monarch), while his sullen, punky companion Mags is portrayed by stage actress and impressionist Jessica Martin in a rare screen appearance. They both, in their own ways, become low-key villains of the piece, with the Captain interested only in his own survival, and Mags having her own secrets (she comes good in the end).

The only other traveller to meet the Doctor and Ace on the way is Nord, self-styled “Vandal of the Road,” a paper-thin but pretty funny joke hardman played by Daniel Peacock (The Comic Strip Presents...). Arriving later, after the Doctor has already reached the Circus, is Whizz Kid. Played by Gian Sammarco, (forever the title character of The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole), Whizz Kid is a specky geek who has been following the Psychic Circus' old tour route and describes himself as its biggest fan. “Oh, I know it's not as good as it was in the old days, but I'm still terribly interested,” he says, a clear, if gentle mockery of the sort of person who made up the majority of Doctor Who fans at the time. He's also besotted with Captain Cook (“I've got all your old journals, and a piece of one of your old shoes...”), who is himself a solid parody of a boring convention guest.

Once inside the Circus, the acts are imprisoned, and forced to perform for the entertainment of the mysterious family that makes up the audience. Up they get, one at a time, to do their party pieces, receiving from the father, mother and little girl a score out of ten, held up on old-fashioned score cards. If they don't pass muster, they're vaporised. If they do well, the Ringmaster assigns them a new act, one they're unsuited for, and so they soon suffer the same fate. The parallels between the TV talent show, which would become more popular during the nineties before virtually taking over weekend airwaves in the twenty-first century are pretty clear. What the serial needs to hammer it home is a larger cast: more contestants and a larger audience, perhaps natives to the planet, complicit in the deadly entertainment and not caring what happens to the ones in the ring.

Against this background is a fairly traditional Doctor Who runaround, with plenty of captures and escapes and daring-do. There's a secret hidden on the old tour bus, guarded by a robotic bus conductor and a giant robot half-buried in the sand, and Mags reveals her own act: she's a werewolf. The monsters are all very kids' TV fare – the werewolf make-up is particularly woeful – but then, this is kids' TV. Yet through his script Wyatt plays with some serious themes that only the adults watching would catch. Bellboy and Flowerchild ran away because of how their dreams of travel, performance and a simple good life were perverted into a cruel and rapacious enterprise. With names like that, it's easy to see that these characters are stand-ins for hippies, the turning of the Circus from something fun and free to something exploitative an allegory for the way the countercultures of the sixties and seventies were subsumed into the corporate, capitalist culture of the eighties.

The cold, inhuman family, munching on their crisps as they send people to their deaths, are revealed to be the Gods of Ragnarok, cosmic entities with statuesque forms, whom the Doctor has allegedly fought “all through time.” Their insatiable desire for entertainment and relentless orders to their staff reflect both the demands of the television audience and its senior management. They even mock the structure of the programme itself, complaining during the boring bits when the action slows down. Their actions don't make a great deal of sense when examined closely – using up and killing all the performers and contestants is hardly a good way of maintaining their entertainment – but it reflects the endless consumerism of modern culture.

The Doctor eventually, after stage-managing events to get himself in the right time-space at the right time, confronts the Gods in their own dimension. McCoy, no stranger to doing peculiar things on stage, had been trained by the magician Geoffrey Durham, aka the Great Soprendo. The Doctor keeps the Gods busy till the right moment by performing tricks (fortunately, it's over before McCoy starts putting ferrets down his trousers). The Gods are defeated, the Circus is destroyed (McCoy walking away from the much-larger-than-expected explosion without batting an eyelid), and those who are left decide to start afresh.

Like Vengeance on Varos three years earlier (and to a lesser extent, 1986's season-long serial The Trial of a Time Lord), The Greatest Show in the Galaxy is very much a story about television; about the demands of the audience; the exploitation of ordinary people who, willingly or unwillingly, become the stars of the show; and, very much, about Doctor Who itself. While it might not have been the show it was in the old days, it was still able to do new, inventive and surprising things, right up to the very end.

Review by Daniel Tessier