The Space Museum

While 21st century Doctor Who frequently explores the strange twists and turns of time travel, the original tended to use it simply as a method to get to a new environment every few weeks. One of the handful of “timey wimey” stories in classic Doctor Who is The Space Museum, a four-part serial which begins with an absolutely brilliant premise, but sadly doesn't make the most of it.

The Space Museum follows on from the previous serial, The Crusade, but with a most unusual time skip. The travellers begin landing the TARDIS while still dressed in the 12th-century clothes they'd acquired in that adventure, before suddenly finding themselves in their normal attire. The Doctor brushes this off as a consequence of “time and relativity,” suggesting he's used to such odd occurrences while travelling in time. Yet more bizarre things start to happen, such as when Vicki drops and smashes a glass of water, which then reforms and refills itself, leaping back up into her hand.

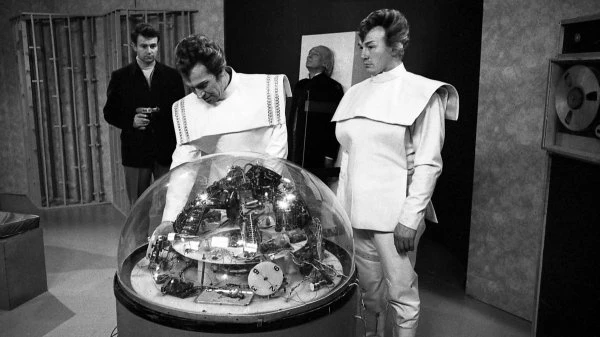

Leaving the TARDIS, the travellers find themselves on an arid planet, home to a museum of spacecraft and other futuristic technology. The planet is silent; the travellers leave no footprints in the dust; and when they explore the museum, the alien guards can neither see nor hear them. They are even able to pass through the objects on display. Even the Doctor can't dismiss this as just one of those things that comes with time-travelling.

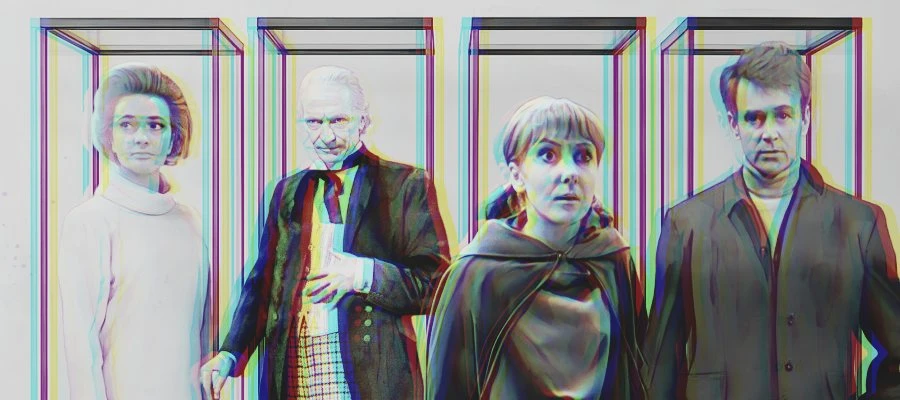

Things become far more alarming when they find the TARDIS itself deeper within the museum, equally intangible, followed by their own bodies, stuffed and mounted as it were, within a glass display case. It's a wonderfully arresting image, just one of many surreal elements that add up to create an unsettling episode. It also presents an entirely new kind of threat to the heroes. The Doctor theorises that the TARDIS has “jumped a time track,” passing through another dimension of time, and that they haven't actually arrived yet. It's nonsense, but compelling nonsense all the same. The travellers are unable to affect the world around them because they're not actually there yet. Once they catch up with themselves at the end of the episode, they are once again back at the beginning of events and must do everything they can to change their future and prevent themselves being captured and made into museum pieces.

The Space Museum was the work of South African writer Glyn Jones, who had been invited to write for the series by script editor David Whitaker, on the strength of his 1963 play Early One Morning. As well as being a director and actor, Jones would become quite prolific screen and stage writer, including as main writer script editor on Here Come the Double Deckers and as a contributor to its predecessor, The Magnificent Six and ½. In 1964 though, when he got the call, he was only starting out in TV, had no science fiction experience and hadn't even seen Doctor Who. Yet he went and wrote one of the most high-concept scripts of the programme to date.

The writer’s experience was similar to that of Bill Strutton, who wrote The Web Planet with no sci-fi experience, and found himself facing an unhappy new script editor in Dennis Spooner. Jones found himself at odds with Spooner over his heavy use of humour in the script, something Spooner wanted to minimise. This is odd, given it was spooner who had been responsible for introducing more humour into the series with The Romans and would end the season with the similarly comical story The Time Meddler. However, these have historical settings, and it seems that he didn’t feel humour and high concept science fiction were compatible.

Hints of the comedy origins of the script remain, particularly at the very beginning of part one, when Ian, finding himself back in his usual suit, remarks: “Doctor, we’ve got our clothes on!” To which the Doctor naturally replies, “Well, I should hope so, my dear boy!” However, such moments are few and far between. This is a shame. With the humour left in, The Space Museum may well have worked a lot better. As it is, after the fascinating first episode it continues with three episodes of stilted, by-the-book rebels-vs-baddies runaround. The Space Museum is located on the planet Xeros, part of the Morok Empire, as a monument to their conquest of the galaxies. The Xerons – people with silly eyebrows – have mostly been shipped off to work on other planets, leaving only the disaffected youth behind. The Moroks – blokes with big hair and different silly eyebrows – have by now moved on to other conquests, leaving Xeros staffed by a handful of penpushers. There are still some fun ideas, with the lead Morok Lobos, who is both colonial governor and museum administrator, being utterly sick of both his jobs and desperate for some action. The idea of a great galactic empire being taken over by bureaucracy, explored through its bored administrators, has the potential to be an early take on The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but too little is made of it. Richard Shaw (Quatermass and the Pit, Freewheelers) is a generally solid actor, but puts no effort into the role of Lobos, who’s meant to be the villain of the piece.

There are some lovely moments with the Doctor, notably his hiding inside a Dalek casing on display within the museum, and the Moroks’ attempt to probe his mind, which is met with all manner of silly imagery, including the unforgettable sight of Hartnell in a stripy Victorian bathing suit. In spite of the heroes’ best efforts, the Doctor is subjected to a freezing process that will prepare him for exhibition. He is saved by Ian – who has become remarkably bloodthirsty by this point – forcing Lobos to defrost him. The Doctor reveals that, while chilled, his “brain was moving with the speed of a mechanical computer.” Aside from the existential horror of actually being aware while standing as a museum exhibit, he seems to have quite enjoyed the experience.

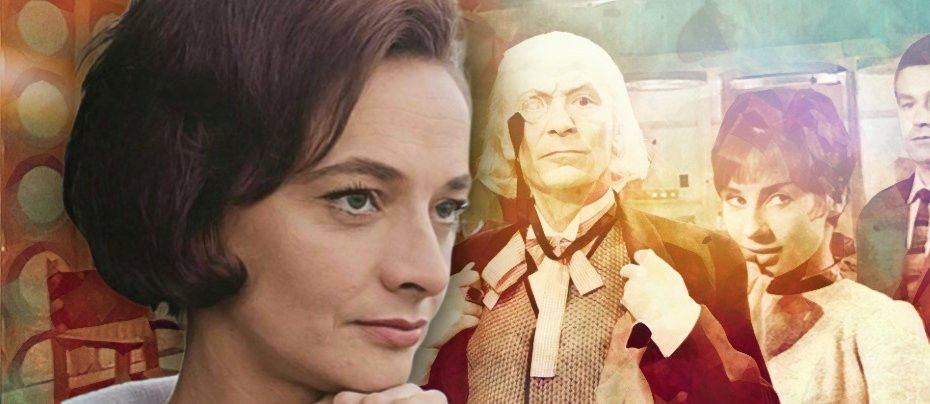

Ian and Barbara are as good a team as ever, with William Russell and Jacqueline Hill still displaying their excellent chemistry. As usual, Barbara is the most practical one but also displays her occasional defeatism. She despairs as to whether it’s possible to change their own future after they’ve seen it but also starts to theorise ways to do just that. The script has hints of some philosophically interesting musings on the nature of fate and time, but as with most elements of the story, there simply isn’t enough of this make any real impression. It’s perhaps unsurprising that, during her seemingly endless wandering from corridor to corridor in this serial, Hill decided to hand in her notice.

Maureen O’Brien is also on top form as Vicki, taking it upon herself to lead the revolution against the Moroks and showing she’s really got what it takes to be the programme’s leading lady. Unfortunately, this is by far the least interesting part of the story, a bog standard Doctor Who runaround. There’s an undercurrent of generational conflict in there, with the Xerons all played by young lads barely out of their teens, against the more mature Moroks. There are decent enough actors among them, including Peter Craze (in his first of three Doctor Who appearances – his brother Michael would be playing new companion Ben at the end of the season) and Jeremy Bulloch (who would later play Hal the archer in The Time Warrior, but is far better known as the original Boba Fett in The Empire Strikes Back).

Unfortunately, they have little to work with. In fact, all the guest cast are saddled with some of the worst expository dialogue in the programme’s history, and their characters are all remarkably stupid. The Moroks are supposed to be morons, it’s in the name, but the Xerons aren’t much better. While the Moroks are dense enough to leave a loaded ray gun on display in their museum, it hasn’t occurred to the Xerons to pick it up and use it.

The Space Museum is one of the last “sideways” stories of the programme’s original conception, that first appeared with the very similar Inside the Spaceship in the early part of season one. From this point on, the series would start to play around with the idea of time itself being both a threat and under threat, but rarely with the same creativity, and certainly not frequently during the show’s original run. Sadly, after the eerie first episode, it really does fall apart. Compressed down to a two-parter, or even reworked as a single episode, it may have worked rather better. It could have made a great episode of The Twilight Zone or Out of the Unknown. As it is, it’s a rather cheap and shoddy story when viewed altogether. Glyn Jones would return to Doctor Who once more, this time in front of the camera, in 1975’s The Sontaran Experiment, the story where they recognised that there just isn’t always enough plot for more than two episodes.

Review by Daniel Tessier