The Crusade

The TARDIS arrives in 12th-century Palestine during the Third Crusade, where the Doctor (William Hartnell), Ian (William Russell), Barbara (Jacqueline Hill), and newcomer Vicki (Maureen O’Brien) arrive amidst a Saracen ambush. Amid the chaos, Barbara is captured and mistaken for royalty by the ruthless El Akir, who presents her and William des Preaux (John Flint) to Saladin’s court. Upon learning their true identities, Saladin (Roger Avon) spares them, intrigued by Barbara’s wit.

Ian seeks King Richard’s help to rescue Barbara but is initially rebuffed. Eventually, Richard knights Sir Ian of Jaffa to add gravitas to his role and sends him to Saladin (Bernard Kay) with a peace offer—marriage between the real Lady Joanna and Saladin’s brother, Saphadin. Joanna, however, angrily refuses. Ian is allowed to continue searching for Barbara but is waylaid by bandits, nearly dying before escaping and recruiting the bandit Ibrahim to help.

Barbara, meanwhile, escapes El Akir twice, ultimately hiding in a harem with the help of Maimuna (Sandra Hampton). As El Akir closes in, Barbara is saved by Haroun (George Little), who kills him—revealing Maimuna to be his long-lost daughter. Ian and Barbara reunite and return to the TARDIS.

Meanwhile, the Doctor, trying to avoid court politics, is arrested by the Earl of Leicester (John Bay) and condemned as a spy. Ian intervenes and, through subterfuge, allows the Doctor to escape with him and return to the ship.

David Whitaker’s The Crusade, first broadcast in March–April 1965, stands as one of the most ambitious and literate historical serials in Doctor Who’s early years. Penned shortly after Whitaker stepped down as the show’s first story editor, this four-part tale plunges the TARDIS crew into the political and religious complexities of a medieval drama—mixing factual history, character-driven plots, and moments of swashbuckling peril.

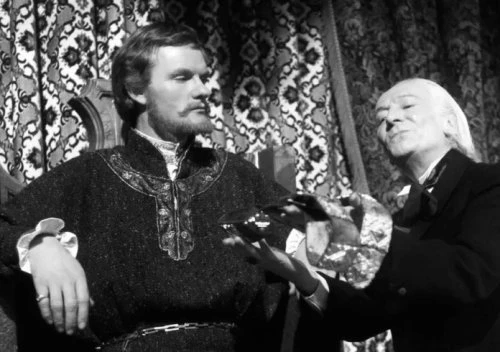

Whitaker’s script, commissioned by producer Verity Lambert to balance the show’s science-fiction with historical fare, is markedly mature and steeped in classical dramatic traditions. It drew heavily on Whitaker’s fascination with the real-life figures of King Richard I and his sister, Joanna. Though elements suggesting an incestuous undertone to their relationship were excised for being too risqué for a family programme—much to actor Julian Glover’s dismay—the central performances still crackle with intensity. Jean Marsh’s Lady Joanna is proud and headstrong, and Glover’s Richard is mercurial and authoritative, a man weighed down by kingship and driven by both duty and desire.

The serial cleverly interweaves two historical events—the failed diplomatic marriage proposal between Joanna and Saladin’s brother Saphadin, and the ambush of Richard near Jaffa—though not in strict chronological order. Dramatic license is used well here, in service of character and tension rather than slavish historical recreation.

Barbara’s capture by the Saracen El Akir (a memorably loathsome Walter Randall) and her subsequent experiences, lend the story its most dynamic plotline. These sequences provide a rare chance for Hill to carry the narrative, and she does so with intelligence and courage, though the serial’s gender politics (typical of its time) have drawn modern critique for misogynistic overtones.

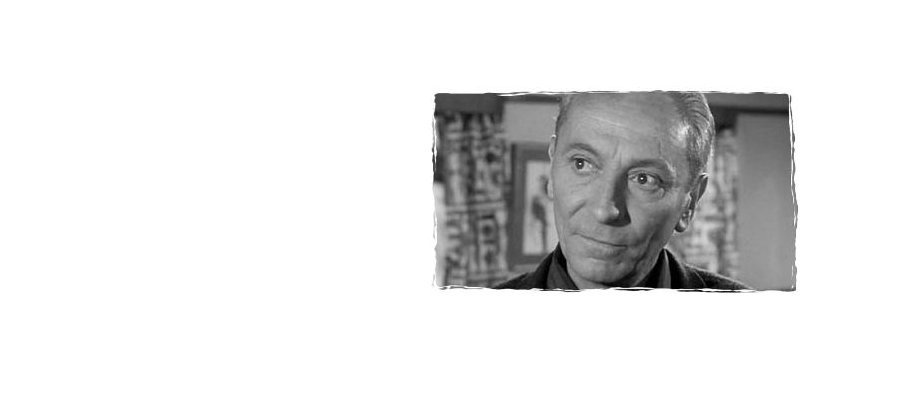

Douglas Camfield’s direction is nothing short of inspired. His prior experience with Doctor Who served him well, but it’s here he proved himself a director of real vision. Camfield brought out the Shakespearean dimension of Whitaker’s dialogue, earning high praise from cast and crew alike. He worked particularly well with Hartnell, who delivered one of his finest and most convincing performances in episode three—subtle, shrewd, and commanding.

The production values are striking. Barry Newbery’s set design, influenced by Jørgen Bitsch’s Behind the Veil of Arabia, is richly atmospheric, successfully evoking the architectural splendour of the era despite limited studio resources. Dudley Simpson’s score, composed for a small ensemble of five musicians, adds a subtle exoticism that complements the drama rather than overwhelms it. Sadly, The Crusade marked Simpson’s final collaboration with Camfield after a personal falling out—one Camfield later regretted.

While initial viewership dipped from its predecessor, stabilising around nine million by the final two episodes, contemporary critical reception was mixed. The New Statesman dismissed it as “wooden” and “charmless”, while Television Mail derided its dialogue as “appallingly flat”. Yet praise did come from some quarters: Television Today hailed both Whitaker’s writing and Glover’s performance. Over time, however, The Crusade has gained a well-earned reputation as one of the finest historicals of Doctor Who’s black-and-white era. The Discontinuity Guide praised its maturity and imagination, though rightly observed it avoids racial stereotypes at the expense of female character depth.

Tragically, only two of the four episodes exists in the BBC archives in full. Episode one was recovered in 1999 in New Zealand, while episode three had long survived; the second and fourth are lost, preserved only via off-air recordings and tele-snaps. The full experience of The Crusade is thus tantalisingly incomplete—but what remains is enough to secure its reputation.

Whitaker later novelised the story as Dr Who and the Crusaders in 1966, expanding it with a lavish prologue and action sequences. It remains one of the better-regarded novelisations.

The Crusade is a literate, provocative, and often dazzling example of Doctor Who as historical drama. While imperfect and occasionally stilted by the mores of its era, it demonstrates the early ambitions of a show willing to step beyond mere escapism into something altogether bolder.

Review: Laurence Marcus