The Robots of Death

Leela: So what happens if the strangler is a robot?

Doctor: Oh, I should think it's the end of this civilisation.

Review by Daniel Tessier

Chris Boucher’s debut script for Doctor Who, The Face of Evil, was followed immediately by the even more luridly-titled The Robots of Death, and, like the first one, it had a far more elegant working title: The Storm Mine Murders. Both titles give us a hint at what to expect but suggest rather different genres: the working title implies an atmospheric mystery story, while the one used for broadcast smacks of a pulpy bit of fifties’ sci-fi nonsense. The actual production gives us a bit of both. It’s a great example of the clever and silly sides of Doctor Who coming together, in a story where the script and design work together to create a classic adventure. It’s even more impressive considering that it was a last minute replacement for another, unworkable script.

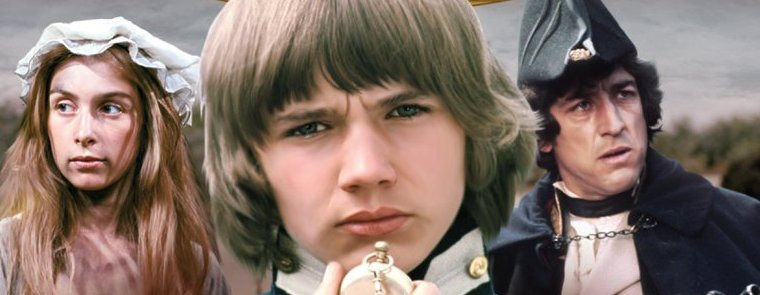

The story sees the Doctor and Leela arrive on a storm mine or sandminer, a sort of roaming mining plant searching a seemingly endless desert for sandstorms to dredge for valuable minerals. The mine has a small crew of humans aided by a team of androids, and almost two years into their tour, tension among the organic crew is rising. The Doctor and Leela waste no time almost getting themselves killed by walking into an ore collector, and discover the body of a murdered crewman, for which they are naturally blamed.

What follows is a murder mystery aboard the sandminer, unearthing a plot that could upend this robot-dependent society. Boucher’s influences for the story are pretty clear. The murder with a whole crew of suspects invokes the works of Agatha Christie, particularly And Then There Were None (also known by other, less-PC titles), although it’s certainly not on the same level: the mystery here is very straightforward. The decadent society, trawling a desert planet for valuable resources, is clearly inspired by Frank Herbert’s Dune. The biggest influence of all, though, is Isaac Asimov’s Robot stories, particularly The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun, themselves murder mysteries set in a robot-dependent society, and the many stories of I, Robot. It’s not really a spoiler to reveal that the murders have been committed by robots – it’s called The Robots of Death, after all. The question is more how they were able to overcome their programmed aversion to violence, and who is behind it.

While Boucher’s script is both clever and exciting, balancing the more thoughtful science fiction questions with plenty of scenes of marauding robots with bloodied hands, the most striking part of The Robots of Death is its design. Ken Sharp was the lead designer on this serial, creating the striking and unforgettable design for the robots. While by necessity the robots had to be played by men in suits, Sharp’s design strikes a balance between clunky costumes and settling for humans with a touch of make-up. The robots display rigid and ornate costumes and masks, with an unmistakable art deco influence, being as much things of beauty as they are functional machines. Their three classes are easily recognisable by a simple colour scheme: almost-black “Dums” lack speech and carry out the most menial tasks; green “Vocs” can speak and are somewhat more sophisticated, while a single silver-green “Super-Voc” oversees the robots’ activities. Regardless of their class, the robots unmoving yet elegant faces and their impeccably polite, calm delivery makes them both attractive bits of kit and utterly unsettling.

Just as striking is the design of the human crew’s costumes, created by Elizabeth Waller in her only contribution to the programme. The crew wear elaborate robes with ornate headwear, both faintly ridiculous yet quite believable as the clothing the wealthy of a decadent society would wear. While they’re ostensibly miners, the crew’s fancy clothing drives home that they are scarcely workers at all, spending much of their time lounging about while the robots do the actual work. While the sandminer itself is functionally designed, the combination of the robots’ design and the costuming makes it clear that this far future society has a sense of aesthetics, a far cry from the usual space people in the series.

It's interesting that from the outset there’s a certain distrust from the humans towards the robots, even as they attend to their every whim. This could be taken as a comment on classism or even the racism inherent in slavery, but the main influence is more obvious: the Uncanny Valley effect of the robots’ appearance – the Frankenstein complex, as Asimov called it. In the story itself, it’s called robophobia, or “Grimwade’s syndrome” – a little ad lib by Baker recognising Peter Grimwade, the production assistant on the serial. This society may have become dependent on robots to function, but it will never be fully comfortable with them, as they are both too human and not human enough. It’s a problem that designers of human-like interfaces have today, as the unpopularity of online AI assistants illustrates. Of course, for all their fancy looks, these robots have the obligatory red lights installed in their eyes to show when they’ve turned murderous.

While the robots are, by their nature, expressionless and emotionless, there is one who somehow stands out as the story’s best guest star. D84, a supposed Dum who is nonetheless able to talk, is on the sandminer to act as an undercover agent to ensure that whoever is sabotaging robot-human relations is stopped. Played with the utmost care and sympathy by Gregory de Polnay (Dixon of Dock Green, The Group, Missing from Home), D84 is quite the sweetest robot you could hope to meet. Speaking in gentle, apologetic tones, he’s irresistibly likeable, and from beneath the mask de Polnay somehow manages to imbue him with expressiveness through head and body movement. The Doctor takes to him straight away, with Baker and de Polnay suggesting that D84 be kept on as a regular companion. While K9 followed only a few serials later, perhaps a helpful robot ally who can go over uneven surfaces would have been a more practical idea.

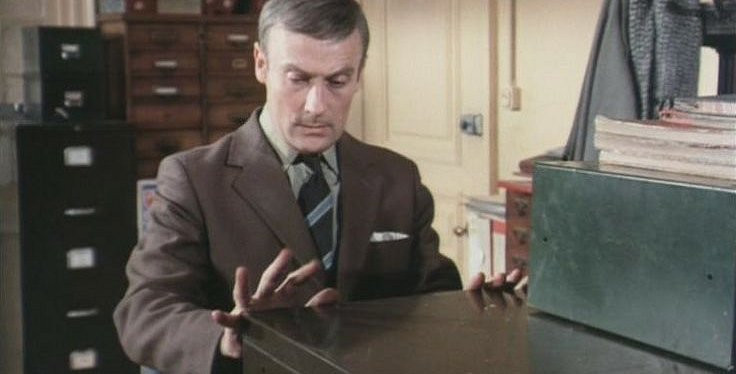

While D84 steals the show with such lines as “Please do not throw hands at me,” the human crew are a fascinating bunch as well. Russell Hunter (Callan, The Gaffer) plays Commander Uvanov, a working-class man who’s done well for himself but who still has a chip on his shoulder.

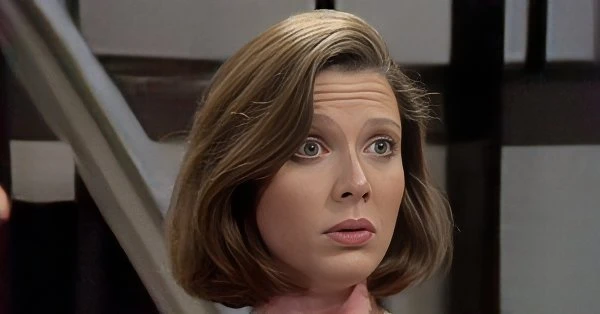

Pamela Salem (EastEnders, Into the Labyrinth, Buccaneer) is, as always, impossible glamourous as Toos even under the most ridiculous of all the hats. David Collings (Sapphire & Steel, Monkey, and formerly the robot R. Daneel Olivaw in Out of the Unknown’s adaptation of The Naked Sun) plays the mysterious Poul, while Brian Croucher (EastEnders, The Jensen Code) plays the gruff Borg and David Bailie (Ransom for a Pretty Girl, the Pirates of the Caribbean series) is the inscrutable Dask. All bring their own flair to this mistrusting crew. Tariq Unus (Tandoori Nights, On the Line) and Rob Edwards (The Practice, By the Sword Divided) don’t get much time to make an impression as Cass and Chub, respectively. The only real weak link is Tania Rogers, who gives a wooden performance as the high-born Zilda.

Boucher is not shy about his influences, laying them bare in his characters’ names: Uvanov clearly invokes Asimov, while Poul is named for sci-fi author Poul Anderson, and the secretive villain Taren Capel takes his name from Karel Ĉapek, the playwright who invented the term “robot” for his 1920 work RUR. While he crafts another excellent script, much credit has to be given to script editor Robert Holmes, who wrote the initial scenes that fleshed out the squabbling crew, and whose deftness of touch can be felt in the throwaway lines that sketch in a much larger world beyond these events. They clearly worked well together, and Holmes was impressed enough with Boucher to suggest him for the script editor role on the upcoming Blake’s 7. Boucher held the position through the series’ entire four-year run, writing nine episode scripts. Several sandminers would follow him: Brian Croucher played Travis in series two, with Bailley, Salem and Collings all taking guest roles.

As with all the best Doctor Who stories, The Robots of Death combines a pacey, intelligent script with strong performances and arresting visuals. The world beyond Storm Mine 4 was intriguing enough to be revisited numerous times beyond the series itself. Boucher followed up The Robots of Death with a direct sequel in his 1999 novel Corpse Marker. Boucher incorporated a character from Blake’s 7 into the narrative, linking the Doctor Who and Blake’s 7 universes. He continued this approach in Kaldor City, an acclaimed audio series published by Magic Bullet Productions from 2001, which saw actors from Robots of Death reprise their roles and some Blake’s 7 regulars appear as well, albeit not always by their characters’ familiar names. More recently, Big Finish has churned out several boxsets of its own audio range set in this world, simply titled The Robots, starting in 2019. Quite rightly, de Polnay returned for both series to provide voices for the star robots.