Doctor Who - Season One - 2005

The 20th Anniversary Review by Daniel Tessier

It’s been an astonishing twenty years since Doctor Who’s triumphant return to our screens, since which time fourteen series have aired, with a fifteenth imminent, along with a stack of specials, plus spin-offs and support programmes. As befits a programme about time travel, the twenty year timeframe seems askew, as if that much time simply can’t have passed. Doctor Who hadn’t even been on the air for sixteen years when it returned (overlooking charity skits and the American TV movie), and somehow we are to believe it’s been another twenty years since then.

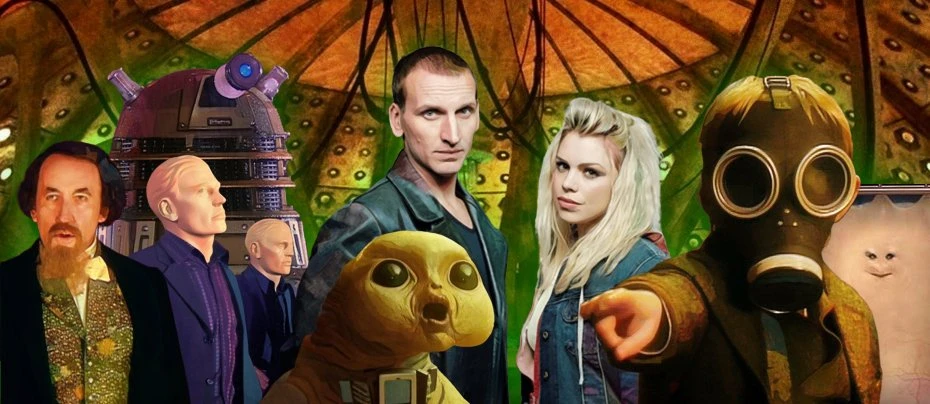

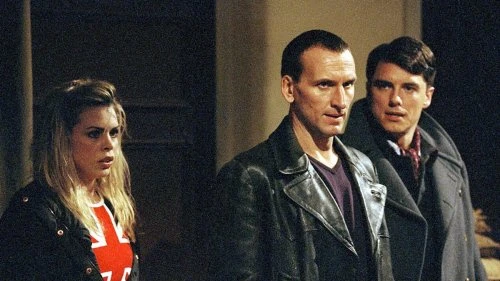

Indeed, with the latest version of the series boasting the same showrunner, executive producers and composer, there’s a sense that Doctor Who has moved far less in that twenty years than such a dynamic show should. Of course, if it wasn’t for Russell T. Davies as the chief writer and overarching creative force on the series, Doctor Who would never have been a success in 2005 and wouldn’t still be running now. Not that Davies can be given all the credit; much of it goes to executive producer Julie Gardener and full-time producer Phil Collinson, who took care of much of the day-to-day work of making the programme. The most visible reasons for its success, of course, were the stars: Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper, who captivated a whole new audience as the Doctor and Rose Tyler.

The odds were stacked against the BBC and their revival of a property that had developed a reputation for being cheap, creaky and childish. The Beeb had experimented with bringing back sci-fi and fantasy drama to the schedules in recent years, but these had generally been either serious and rather worthy (Sea of Souls, Strange) or self-parodic (Randall & Hopkirk (Deceased)). Of course, there was always space for fantasy on children’s TV. It was Jane Tranter, then Head of Drama Commissioning, who saw the opportunity to revive Doctor Who, capitalising on these earlier experiments and embracing a programming slot that was considered extinct: the Saturday evening family drama. Recruiting Gardner, who brought on Davies – famously a Doctor Who fan – Tranter commissioned the new Doctor Who as a major production that would appeal to children, teens and adults, bringing them together to watch a series that wasn’t designed to appeal to a narrow demographic. It was a gamble; according to received wisdom, families just didn’t watch TV together like this anymore, especially not drama and most certainly not fantasy.

Davies took the commission and reinvented Doctor Who, taking everything he loved about the original series and updating it, ditching anything he felt didn’t work and learning lessons from the intervening years of television. In spite of his well-known enthusiasm for Doctor Who, his previous work didn’t suggest he was the sort of writer who would work on such a series. Critically well regarded for hard-hitting dramas such as Queer as Folk and The Grand, he had most recently made waves with his powerful religious drama The Second Coming, which had starred Eccleston as the reborn Son of God. His earlier supernatural soap opera Springhill, created with Paul Abbott and Frank Cottrell-Boyce, was blackly humorous and dealt with extremely weighty themes. To find something genuinely Doctor Who-like on his CV, you had to go back to his very earliest creations, the children’s series Dark Season and Century Falls (the former of which, in particular, comes across as a final season of Doctor Who made on no budget at all). Meanwhile, he and Gardner had made the miniseries Casanova, by far the most Doctor Who-like of their output, but which was only broadcast just before Doctor Who. (the third episode airing the day after “Rose”).

All of this shows that while Davies may not have appeared a likely person to reinvent Doctor Who as a successful family show, he was actually perfect. With a genuine love for television and an understanding of what made different kinds of drama work, he was able to take the disparate elements of Doctor Who’s strange history and combine them with modern drama to make something unique and compelling. Still, the first series, while a brilliantly constructed and fabulously entertaining run, is also a messy, seat-of-the-pants affair, one where it’s very clear that everyone involved is working it out as it went along. More controversial news from behind the scenes has come out over the years, making it something of a minor miracle that the series was made at all.

Among other contemporary series, Davies referred to Buffy the Vampire Slayer as a template for the new Doctor Who. Buffy, which finished airing shortly before production on Doctor Who began, was a genre show that reached a broader appeal across demographics than anyone expected. Fast-paced and youth-oriented, it used fantasy and horror tropes to explore everyday teen problems while building an elaborate mythology of its own. With this in mind, the casting of Billie Piper as Rose was an obvious move. Best known at the time for her pop career, Piper had returned to her chosen career as an actor, gaining critical applause for her role in the BBC’s 2003 reworking of The Canterbury Tales. As Rose, Piper was the identification figure for the audience; an ordinary young person who was thrown into the bizarre world of Doctor Who. Through her eyes, the new audience could explore and learn about this universe. Not for nothing is the first episode named “Rose” – everything is seen through her eyes as the Doctor and his enemies intrude upon her life.

Unlike the pretty posh characters who generally headed the original Doctor Who, Rose was common and proud of it, with much of the series taking place in and around her home on the fictitious Powell Estate in London. Working in a shop and living with her mum, Rose is as ordinary as they come, but importantly, this doesn’t make her any less remarkable or impressive. Rose adapts to her new life with ingenuity and courage, with Piper’s incredibly likeable and relatable performance making her central to the success of the new series.

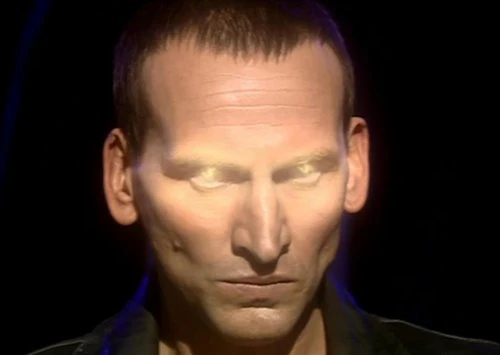

Christopher Eccleston, on the other hand, is just about the least Buffy-ish actor who could have been cast. While not a stranger to lighter drama and comedy, Eccleston was best known for serious, hard-hitting working class dramas such as the classic Our Friends in the North and his regular role in Cracker. His casting as the Doctor – generally seen as an outlandish, silly character – was unexpected, and lent the new series an air of credibility. Eccleston’s casting was very against type for the Doctor, who was comprehensively reinvented for this new iteration. Even more so than Rose’s council estate roots, the Salford-born Eccleston’s casting as the Doctor removed the poshness of the original. Gone were the frock coats and colourful costumes; Eccleston’s Doctor wore a leather jacket and casual, practical clothing. The Doctor no longer spoke like an early 20th century professor, but like an ordinary bloke, with Eccleston’s embracing his natural accent (hence the classic line, “Lots of planets have a north!”).

The first episode highlights Davies’s new approach to Doctor Who. Fast paced and colourful, humorous and dramatic in turns, it reintroduces the Doctor and his status as a wandering adventurer, out to see the universe, righting wrongs as he goes. Eccleston’s performance is camper, sillier and more casually charming than most would have expected, but he is able to switch to a more intense, dramatic style at a moment’s notice with the character’s loneliness clear to see. Piper is immediately engaging as Rose, whose story is easy to grasp: she’s settled into her life but fundamentally bored and unfulfilled until she stumbles into the Doctor’s latest mission. We meet the other main people in her life, her mother Jackie and her boyfriend Mickey Smith, who will remain prominent characters throughout the first and second series.

Davies knew exactly what parts of Doctor Who’s sprawling history to include and what to throw away. The TARDIS is, or course, non-negotiable, with the blue Police Box exterior being so iconic that there was never any chance it would be changed. In 1963 it was a symbol of ordinary British life; in 2005 it simply means TARDIS, leaving it as a baffling object for the characters themselves. Its interior is redesigned, now somewhat organic and cobbled together and far larger than we had previously seen, making the impossible nature of the TARDIS even starker than before. The sonic screwdriver, the all-purpose, get-out-of-anything tool is brought back to help streamline the plots (not always to their benefit); otherwise, the Doctor is free of the trappings of his past. Notably, a side plot with Mark Benton (also of The Second Coming) as the geeky Doctor-enthusiast Clive, fills Rose and the audience in on the Doctor’s existence across history, but there’s no hint of his origins or his many previous faces. Aside from a brief line (“That’s your Doctor there, isn’t it?”) and the Doctor’s critical reaction to his reflection, there’s no hint that he’s ever looked any different. Existing fans knew better, but new viewers weren’t bogged down with the concept of regeneration at such an early stage.

The most notable blast from the past is the opening episode’s enemy: the alien Nestene and its plastic servants, the Autons, previously seen facing Jon Pertwee’s Doctor in 1970 and 1971. Living shop mannequins are a straightforwardly creepy monster, and they work just as well here as they did in the seventies. The script is very straightforward, but this suits an introductory story, and while Murray Gold’s music can be overbearing and some of the effects looked ropey even then, “Rose” stands up as an exhilarating relaunch of Doctor Who.

One innovation of the new series was the “Next Time” trailer, a brief glimpse at the upcoming episode to whet the appetite of the viewer. Following the first episode with this was especially essential, showcasing that Doctor Who was a series that could go anywhere and do anything. In the event, the first series was set entirely on or in orbit of Earth, but the trailer for episode two, with its parade of colourful aliens and its distant future setting made it clear that each week the audience could switch on to a completely different adventure.

“The End of the World” used up the bulk of the series’ special effects and prosthetics budget to show us just how bizarre and colourful this show could be. Pulling out all the stops to impress Rose, the Doctor takes the TARDIS to Platform One in the orbit of the dying Earth, five billion years into the future. It’s an immediate statement that the whole of history is the Doctor’s playground, as well as making it clear that the series can do different kinds of stories. “The End of the World” states quite simply that the Earth’s days are numbered, and instead of trying to save it, presents a simplistic murder mystery as someone tries to bump off the wealthy aliens who have gathered to watch the planet burn up in the expanding sun.

Most of the elaborate creatures get little or nothing to say – not even the immediately iconic giant head in a jar, the Face of Boe – but are suitably impressive nonetheless. Those that get to be actual characters include the Steward in charge of events (an entertaining Simon Day) and Rafallo, a plumber (an incredibly likeable turn by Beccy Armory), both blue-skinned humanoids; and the human-like, hyper-evolved tree Jabe (a flirtatious Yasmin Bannerman). They all die horribly, of course. The villain of the piece – and it’s not like it isn’t obvious – is Zoe Wannamaker’s delightfully bitchy Lady Cassandra. Ostensibly the last “pure” human and the last to be born on the planet Earth, Cassandra has spent the centuries undergoing endless cosmetic surgery until she is nothing more than a panel of stretched skin in a frame connected to a brain in a jar. An obvious attack on the cult of youth and beauty, but an effective one.

It's a fundamentally silly episode, with a climactic sequence involving spinning fan blades of the sort that Galaxy Quest had sent up years earlier and a villain with a nonsensical plan, but “The End of the World” is tremendous fun and sees the new Doctor Who shouting, “look what we can do!” In spite of all the bizarre creatures and far future setting, it’s still essentially about Rose and how her life is reflected through her new experiences. Davies stated in numerous interviews how he was averse to visiting “the planet Zog,” and that he felt all Doctor Who stories should return to Earth and recognisable humanity. He’d move beyond this to an extent over the years, but the close ties to contemporary Britain never leave his version of Doctor Who. Even amongst all this strangeness, Rose is able to phone home, and the episode ends with her and the Doctor discussing going to get chips. Davies uses this most ordinary scene to drop in his own version of the series’ mythology: the Time War. The Doctor admits that he is a Time Lord, and that he is also the last of his kind, the others having been wiped out in a vast war. It’s a reversion to the earliest conception of Doctor Who, in which the Doctor was essentially unique and cut off from his home, discarding years of continuity in favour of a simpler, easy to understand backstory. In a more meta sense, the Time War stands in for Doctor Who’s long hiatus: it’s what the Doctor has been dealing with while his show was off the air.

Following this trip to the future, the third episode takes us to the past, with the new series’ first guest script. Mark Gatiss, now probably best known for Sherlock but then for The League of Gentlemen, had cut his teeth on semi-official Doctor Who spin-off films in the early nineties, such as the PROBE series. He had been a prolific contributor to Virgin Publishing’s nineties novel range, Doctor Who – The New Adventures, and was known as something of a traditionalist, with a love of classic horror, gothic literature and good, old-fashioned sci-fi. He was pretty much the most obvious person to write for the new Doctor Who and would go on to contribute scripts to nine of the first ten series. “The Unquiet Dead” is perhaps the story that most perfectly suits him: a Victorian ghost story with a sci-fi twist, with plenty of literary jokes and references.

The Doctor erroneously takes Rose to Christmas Eve 1869 in Cardiff (he was aiming for Naples). The revived Doctor Who was made by BBC Wales and filmed largely in Cardiff, an while it often subbed for London, setting some episodes there was always part of the deal. Oddly enough, then, the first episode to be set in Cardiff was largely filmed in Swansea, with scenes in Monmouth and Penarth, since Cardiff doesn’t look sufficiently Victorian. Doctor Who would go on to have its first of many Christmas specials at the end of the year; had the production team known this, Davies may well have kept this storyline back. As it was, we got one of Doctor Who’s most festive episodes in early April, as none other than Charles Dickens himself is assailed by phantoms at Christmastime.

Simon Callow had already made playing Dickens something of a career-within-a-career, portraying the author in a handful of films and a one-man show, as well as writing extensively about him. Despite this, Callow is notoriously picky about playing Dickens, so it’s a testament to the script that he considered Doctor Who’s version of the author as worthwhile. Taking place right at the end of the writer’s life, “The Unquiet Dead” sees Dickens lacking inspiration and surviving on past glories, before being forced to open his eyes to new ideas when he is drawn into an alien plot. The Gelth, ghostly, gaseous aliens, have broken through a rift in space/time and are stealing the bodies of the recently dead to replace their own.

“The Unquiet Dead” seems to exist partly to show just how Victorian the new Doctor isn’t. While Rose changes into a beautiful, period-appropriate dress, the Doctor – once a champion of frock coats, spats and cravats – sticks to his leather jacket and jumper. He sticks to his usual style of speech (in spite of Gatiss’s reported difficulty letting go of pompous, Pertwee-style dialogue) and basically sticks out like a sore thumb. On the other hand, he is star-struck when he meets Dickens, describing him as his number one fan, showing how literature and theatre don’t have to be reserved for the upper classes. He only throws his authority around when fighting to help the Gelth with their plan, manipulated by his guilt for their near destruction in the Time War.

It's a simple, fun episode that belts along, helped by a hilarious turn by Alan David as undertaker Sneed, and a strong performance by Eve Myles as his clairvoyant servant, Gwyneth. The episode also helps set up major developments in the series’ future, with the Cardiff Rift being a central element of spin-off series Torchwood, which starred Myles as Gwen Cooper.

The next story is the series’ first two-parter, which therefore features the first cliffhanger of the revived series. Cliffhangers endings were such a fundamental part of the original Doctor Who that the decision to rework the series with largely standalone, self-contained episodes convinced some fans that it couldn’t possibly work. “Aliens of London” and “World War Three” make for an awkward story, and it’s clear to see that Davies and co. haven’t quite figured out what sort of series this is going to be. While the shifts in tone between episodes are a feature of the series and it’s designed to be kid-friendly, rarely is it as children’s TV as it is here. Introducing the series’ first major new aliens, the big, green, baby-faced Slitheen, it undercuts any threat by having them deliver puerile dialogue and continually break wind. Although this does lead to the Doctor’s unforgettable line, “Do you mind not farting while I’m saving the world?” it’s impossible to take the monsters seriously. Add to this the fact that the aliens can only fit into the stolen skins of fat people, and it’s all a bit feeble.

On the other hand, the story deals with some hefty emotional themes, and the cast are all doing everything they can to elevate the script. The Doctor, in a moment of legendary carelessness, brings Rose home a year late, forcing her to deal with a grieving and distraught Jackie and unable to explain where she’s been. Mickey, having been the last to see her before she vanished, has been fighting accusations of her murder. In the middle of all this “domestic stuff” as the Doctor puts it, an alien ship crashes into the Thames. An alien invasion is faked to cover the Slitheen’s real plot, with a cybernetically-altered piglet let loose as a decoy alien (Jimmy Vee, resident little person on Doctor Who and its spin-offs). It’s a testament to Eccleston’s acting ability that when he cradles the dying pig in his arms after a soldier shoots it, furiously and mournfully telling him that it was just scared, you really feel for both of them.

The guest cast mostly do good work, with Rupert Vansittart and Annette Badland standing out for giving their characters, the Slitheen-ified General Asquith and Margaret Blaine, just the right balance of sinister villainy and broad comedy. It’s Penelope Wilton who really shines, though, as humble backbencher Harriet Jones, whose insistence on filing her request on cottage hospitals in the midst of a national crisis leads to her becoming an unlikely ally to the Doctor and Rose. Camille Coduri and Noel Clarke, neither of whom had the best material to work with in the opening episode, fare much better here. Unfortunately, the drama promised by the clash of Rose’s dangerous new life and her old life on the Estate is undercut by the comedy aliens, with the much of the production seemingly aimed at very young children, and other parts that could be straight from an episode of Bottom. There are little connections to the wider story of Doctor Who, though, with a brief appearance the military organisation UNIT – first introduced in the 1968 serial The Invasion and a mainstay of the Pertwee era in the early seventies. The Doctor notes that he’s “changed a lot since the old days,” another hint at his earlier adventures. Looking forward, Naoko Mori has a role as pathologist, which would lead to her being cast as Toshiko Sato on Torchwood (apparently, if improbably, the same character).

Episode six sees another massive lurch in tone as we get one of Doctor Who’s best and most powerful episodes. “Dalek” reintroduces the Doctor’s most persistent enemy, rethought and revamped for the 21st century. The Daleks were emblematic of the public’s perception of Doctor Who before it was revived: iconic, recognisable, and ultimately rather silly. Years of jokes about them being unable to climb stairs and being armed with a sink plunger and egg whisk meant that it had become hard to take them seriously. Davies recruited award-winning playwright Robert Shearman, who had written the 2003 audioplay Jubilee for Big Finish, which had used a captive Dalek as part of a harrowing story. Using Jubilee as the basis but thoroughly reworking it, Shearman wrote “Dalek,” in which the Doctor is brought face-to-face with the last surviving Dalek, held in an underground bunker by a wealthy collector of alien artefacts.

The Daleks have been the Doctor’s antithesis since they first appeared in 1963, but Davies’s new backstory for the series gave them even greater prominence: it’s revealed that they were the enemy the Time Lords fought in the Time War. It’s also revealed that the Doctor destroyed them all at the end of the war (and, by implication, the Time Lords as well). The meetings between the Doctor and the battered, chained-up Dalek are electrifying. Eccleston chose to play it as a Holocaust survivor encountering a Nazi prisoner, viciously and vengefully mocking and attacking the Dalek in an almost unhinged manner. On the other side, Nicholas Briggs – number one monster voice provider for Doctor Who for Big Finish and the modern TV series – gives an incredible performance as the Dalek, humanising it just enough while retaining most of what makes its voice so unsettling. The Dalek is lost and desperate for direction, dealing with torture and abuse, and evokes real sympathy. It’s easy to see why Rose – who has, of course, never heard of the Daleks – takes pity on the it.

The triumph of the script is that, while the Dalek is a pitiful and sympathetic figure, it’s also a cunning and brutal one. It uses Rose’s concern for it to coax into touching it, which (in a moment of “just go with it” technobabble) allows it to revitalise itself and escape. What follows is a prolonged display of the Dalek showing just why it shouldn’t be underestimated, as it glides effortlessly up stairs, crushes skulls with its plunger, and exterminates people by the dozen. Meanwhile, Henry Van Statten, the billionaire who has locked it away, desperately tries to stay alive along with the Doctor and what little remains of his staff. While the Dalek still garners sympathy even as it gleefully kills, Van Statten – thanks to a truly hissable and arrogant performance by American actor Corey Johnson – is utterly unlikeable throughout the episode.

Both Eccleston and Piper are remarkable in this episode, giving intense, real performances as they face the Dalek in their contrasting ways. They are joined by Coronation Street’s Bruno Langley as Adam Mitchell, boy genius on Van Statten’s staff, and international actor Anna-Louise Plowman as his PA Diana Goddard, but the best material sees them facing off against Van Statten and the Dalek. At the end, the Dalek, having been infected by Rose’s humanity, destroys itself, supposedly rendering its species extinct. (Spoiler alert: this is not the case.) It’s an incredible episode, essentially acting as a second launch for the series and showing just what it was capable of, yet it was almost undone before filming began. Early negotiations with the estate of Terry Nation – original creator of the Daleks in 1963 – meant that the BBC almost couldn’t use the iconic aliens, leading to numerous rewrites as they were taken out of and then put back into the script. Given how much of a mainstay the Daleks have been in revived series, it’s hard to imagine what it would have been like had an agreement not been reached.

“Dalek” leads directly into episode seven, “The Long Game,” a title that only makes sense at the end of the series. The main purpose of this episode is to demonstrate why Rose is an ideal companion for the Doctor, by making it clear that short-term tag-along Adam doesn’t measure up. Langley does what he needs to do, making Adam far too wet and unlikeable to root for, but in both his episodes he and Piper display such an utter lack of chemistry that the briefly hinted at romance between them is laughable. The episode was given the working title “The Companion Who Couldn’t” in Davies’s initial series outline but actually has its origins in a script he pitched to Andrew Cartmel, Doctor Who’s script editor in the late eighties. Indeed, you can see how this would have worked with Sylvester McCoy, stretched out a little and chopped into three short episodes. It has a straightforward plot where the Doctor saves the day by talking a new character into doing something proactive, and the sets and costuming are so cheap that it wouldn’t have looked very different if it had gone out in 1989. Aside from the CGI monster, the only thing that would have looked futuristic then are the extras’ costumes, and that’s because everything has clearly been bought on the high street in 2004.

Straightforward though it is, the story works. The Doctor brings Rose and Adam to Satellite 5, another space station in orbit of Earth in the year 200,000, only to find that there’s little evidence of the Great and Bountiful Human Empire he was expecting. Satellite 5 controls the news and media for the entire galaxy, influencing how people think and act, a storyline that was just as topical in the eighties and in 2005 as it is now. The people working on Satellite 5 help process the broadcast data through implants in their brains, leading Adam to sneak off to get his own surgery, enabling him to send millennia’s worth of technical data back to his home in the past using Rose’s souped-up mobile phone. Meanwhile, Rose and the Doctor are asking the right questions, and set about finding out just who’s controlling Satellite 5 itself.

The episode’s guest cast really helps it. Anna Maxwell-Martin, soon to be a BAFTA winner for Bleak House, has the small but vital part of Suki, a supposedly innocent employee of Satellite 5, while Christine Adams, then still new on the scene but soon to be a successful actress in the US, plays Cathica, another employee spurred into action by the Doctor’s words. Tamsin Greig, then best known for Black Books, shows what a fine comedy performer she is with a faultless performance as the nurse who provides Adam’s brain surgery. Simon Pegg plays the episode’s main villain, the Editor, after his success with Spaced and Shaun of the Dead but before he became Hollywood’s king of the geeks. Originally cast as Pete Tyler in episode eight but forced to drop out due to a scheduling conflict, Pegg is clearly having the time of his life playing a Doctor Who baddie, so can be forgiven for getting a bit hammy at times. The real villain behind it all, giving the Editor his orders, is a thrashing CGI blob that’s mostly notable for its wonderfully over-the-top name: the Might Jagrafess of the Holy Hadrojassic Maxerodenfoe. The real villains behind the Jagrafess wouldn’t be revealed until the final story, when this episode would retroactively appear far more important than at first glance.

Episode eight is the emotionally intense “Father’s Day,” written by Paul Cornell. Another Big Finish veteran and one of the most influential authors of the New Adventures novels, Cornell also had considerable television experience, largely as a writer for medical dramas including Casualty and Children’s Ward (the latter also an early credit for Davies). Cornell has been considered the writer who introduced emotional depth to Doctor Who with his novels, so it’s unsurprising that he was given this episode to tackle. “Father’s Day” sees Rose ask the Doctor to take her back to 1987, to the day her dad was killed in a hit-and-run when she was still a baby. Rose just wants to be there so she can meet him and so that he doesn’t die alone, but the temptation to interfere is too much for her. There’s not as much made of the eighties setting as you might expect, although it’s notable that this is only the second time that Doctor Who set a story during its own run. The previous time was Remembrance of the Daleks, set in 1963 at the time the series started, and broadcast only a year after this episode is set. (The upcoming 2015 series is said to feature an episode set in 2007 – exactly the same time difference as in “Father’s Day.” Time marches on.)

It's an episode that almost seems to come from another version of the series, where the Doctor is a father figure to Rose instead of the love interest he’s already becoming. The script goes out of its way to ensure that the characters are placed in unique circumstances, so that we don’t wonder why this sort of thing happens every time they go into the past: the Doctor takes Rose back to see her father at his death, she finds she can’t do it, he takes her back again – weakening time – and then she panics and pushes him out of the way of the car. This alters history in a catastrophic way, with interdimensional monsters called Reapers descending and devouring anyone in the vicinity to “cleanse the wound.” It doesn’t make a lot of logical sense, but it’s dramatically powerful, with the Doctor, Rose (adult and infant), her parents, a very young Mickey and a whole wedding party hiding in a church while the Reapers circle outside and the Doctor desperately tries to think of a way to fix things.

Eccleston gives a reliably great performance as the Doctor reacts angrily at Rose’s actions, although you can hardly blame her, and really, it’s the 900-year-old time traveller who should have known better than to bring her into temptation’s way. Piper gives perhaps her best performance of the series, an absolutely stunning turn as Rose deals with the emotional onslaught of meeting her dad and then losing him again. However, it’s Shaun Dingwall’s performance as wideboy Shaun Tyler, the well-meaning but somewhat useless man who Rose has built up as a heroic figure, that really carries the episode. His realisation that Rose is his daughter, and later, that he could stop the crisis if he steps back out in front of the car that should have killed him, are achingly well played. No one knows how Simon Pegg would have played Pete, but given how perfect Dingwall is in the role, it’s a good thing Pegg wasn’t available for this recording.

There are some great moments in the episode, such as when the Doctor opens the TARDIS to find it’s reverted to an empty box, or his heart-to-heart with the almost-married couple, lamenting that they’ve had a life he can never have. It’s the moments between Rose and Pete that make the episode such a winner though.

Episodes nine and ten, “The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances,” make up our second two-parter, a story that has a good claim to be the best of this first series. If “Rose” relaunched the show and “Dalek” announced it had really arrived, “The Empty Child” showed it firing on all cylinders. This is the first Doctor Who script by Steven Moffat, aside from the legendary Comic Relief skit The Curse of Fatal Death. At the time best known for the sitcom Coupling, Moffat became one of Doctor Who’s most celebrated writers, taking over from Davies as showrunner in 2010 and co-creating Sherlock with Mark Gatiss that same year. “The Empty Child” is a great example of just why Moffat’s stories are so popular, delivering humour, drama, adventure and a hell of a lot of flirting. It’s also the first time the revived series really tried horror; “The Unquiet Dead” was spooky, but this was genuinely chilling.

Arriving in 1940s London in the middle of the Blitz, the Doctor and Rose are tracking down an alien ship that would have crashed somewhere recently. They are quickly separated, investigating the ship from opposite directions. Rose falls in with 51st century time traveller Captain Jack Harkness, played with outrageous charm by John Barrowman. Now making a living as a galactic conman, Jack wastes no time charming Rose to his side, believing her to be a time agent who will buy his merchandise – the crashed ship. This was the beginning of a renaissance in the Scots-American actor’s career that would see him lead Torchwood the following year and go on to take a major role as Merlyn on Arrow and its spin-offs, as well as becoming an even more regular presence as a presenter and theatrical performer. Since then, details of Barrowman’s inappropriate behaviour on set have scuppered his career, but in 2005 he swept into Doctor Who like a flirtatious force of nature.

Meanwhile, the Doctor falls in with a bunch of homeless kids lead by surrogate mum Nancy, a young woman who scouts likely houses to raid for food during air raids. However, the kids – or as it turns out, Nancy – are being stalked by the eponymous Empty Child, a small boy in a gas mask who relentlessly follows them, continually asking “Are you my mummy?” Young Albert Valentine is incredibly chilling as the haunting little boy, helped by some uncanny direction by James Hawes. It’s Florence Hoath as Nancy, though, who really impresses, giving an incredibly heartfelt performance as someone lost in her life, desperately trying to make up for the responsibility she’s run from. Hoath took on a regular role on soap opera Family Affairs around this time, but after its cancellation took only a few roles before quitting acting around 2008. It’s a shame, as she was an excellent actor, but at least the little ones can enjoy her on her own children’s YouTube channel Zinnipops.

The first part ends on a cracking cliffhanger, as the Doctor is reunited with Rose and Jack in a hospital staffed only by the ailing Dr. Constantine (a dignified performance by Richard Wilson). Constantine is caring as best he can for the Child’s victims – people who have been infected by his inhuman nature, mutating into zombies with gas masks fused to their faces. “Physical injury as plague,” intones Constantine, before terrifyingly succumbing to the transformation himself. The second part, “The Doctor Dances,” lives up to the promise of the first, with plenty more chilling moments, although it spends a lot of its time on the triangle building between the Doctor, Rose and Jack. The euphemism that the human race will, in the far future, travel the stars, meet other species and “dance” with them, as the omnisexual Captain Jack flirts with anything that moves, extends to the Doctor hinting that, yes, of course he’s danced a few times in his life. (It shouldn’t be that much of a shock: he has a granddaughter, after all.) The outlook seems bleak for the trio, but when Jack accepts that his stolen alien ship is the cause of the crisis and the Doctor reunites the Child with his mummy at last, it ends with a truly triumphant victory as, for once, “Everyone lives!”

Episode eleven, “Boom Town,” is something of a filler episode, written by Davies to replace earlier planned ideas. At once stage, acclaimed television writer Paul Abbott was scheduled to write the episode, which would have been about how Rose had been somehow created to be the Doctor’s ideal companion. A fascinating idea, and one that would have likely sent the series down a very different route, it was dropped early on due to Abbott’s other commitments. Davies also included the option of a Pompeii-set episode in this slot in his initial series outline, but this would have proven too expensive for the series’ remaining budget. (This would eventually become “The Fires of Pompeii,” broadcast in 2008 as part of the fourth series.)

Instead, we got an introspective episode that largely exists to fulfil the series’ remit of showing off 21st century Cardiff. The Doctor brings the TARDIS to the city centre to refuel off the Rift, allowing himself a brief holiday, hanging out with Rose, Jack (sticking around on the TARDIS), and Mickey (asked to come along by Rose on the spurious excuse of bringing her passport). Their jolly is cut short when the Doctor sees Annette Badland in the local paper, back as Margaret Blaine aka Blon Slitheen, having survived the events of “Aliens of London” and set herself up as Mayor of Cardiff.

The early teaser blurb for this episode advertised it as featuring “an enemy thought long since dead.” You can imagine the feverish speculation of Doctor Who fans, wondering which of the many great villains of the classic series would be back to face the new Doctor. Doctor Who vs. Margaret was a bit of a disappointment. Nonetheless, watched on its own merits, “Boom Town” is a quietly effective episode for most of its run. The first act is genuinely funny, with Slitheen fart jokes kept to a minimum, before it lurches into a darker tone as the Doctor commits to taking Margaret back to her home planet, where she faces the death penalty – just as soon as the TARDIS has refuelled.

Margaret confronts the Doctor with the blood on his hands, accusing him of being no better than her for condemning her to death. This is pretty rich, given that she was going to destroy the Earth for profit and is now planning to wipe out Cardiff as part of an escape plan, but it leads to some tense scenes between the two of them. It’s no, “You would make a good Dalek,” from episode six, and it smacks of the false equivalency of so many of these dramatised debates, but it allows Eccleston and Badland to play off each other effectively. Actually, more interesting is the interplay between Rose and Mickey, who go from rekindling their romance to at each other’s throats in minutes, as Mickey learns to stand up for himself and we get a glimpse of the possessive, more selfish Rose we’ll see more of in series two. The final act sees the action start, as Margaret’s secret back-up plan goes into effect, but the plot is effectively switched off by a literal deus ex machina, robbing us of any real resolution. It does set up some of the elements that will come into play in the finale, though.

And what a finale it is. Episodes twelve and thirteen deliver a climactic event of the kind never seen before on Doctor Who, a clear example of Davies running with a Buffy-style confrontation with a Big Bad villain. Before viewers reached the finale, though, there were two major talking points that had run almost since the beginning of the season; one on-screen, the other behind the scenes.

The first episode, “Bad Wolf,” told us straight off the bat that there was an answer coming to one of these. That seemingly innocuous two-word phrase had first been uttered in the second episode and had gone on to appear somewhere in almost every episode since, be it in dialogue, call signs, graffiti, even the name of Cardiff’s power plant. Here, it was the Bad Wolf Corporation seemingly behind the sinister events of the story. It wasn’t long before regular viewers noticed it and began wondering what it meant, and the characters even caught up eventually. In the event, it wasn’t the episode “Bad Wolf” that resolved the mystery, but the second part, the ominously titled “The Parting of the Ways.”

The second major talking point was more mundane, but also more important. Between the broadcast of the first and second episodes, it had been leaked that Eccleston had declined to renew his contract and would not stay on for a second series. The BBC hastily released a press statement, claiming that the actor wished to avoid typecasting: something he had never said, and which the Beeb had to retract and apologise for. Eccleston remained tight-lipped on his actual reasons for years, but it became apparent that he had an unhappy experience filming the series, and took exception to the culture the cast and crew were working under, in particular how some of the lower-level staff were treated. Eccleston’s leaving kicked the rumour mill into overdrive, but there was only ever one likely candidate for his replacement. David Tennant, star of Davies and Gardner’s hit Casanova, was both a huge Doctor Who fan and clearly on the cusp of becoming a major star. His performance as the eponymous adventurer had been to convince most viewers – and, more importantly, Davies – that he was perfect for the role of the Doctor. His casting was announced a fortnight after Eccleston’s departure was leaked.

So, while there was a clear direction for this story to go, how we’d get there was a mystery, and was ultimately a mixture of the predictable and the bafflingly odd. “Bad Wolf” begins with the Doctor finding himself in the Big Brother House (something of a coup in itself, involving an unlikely agreement with Channel 4). Rose finds herself a contestant on a futuristic version of The Weakest Link, complete with Anne Robinson voicing the “Anne Droid;” while Jack faces robotic versions of Trinny Woodall and Susannah Constantine on What Not to Wear. Davies has often been vocal of his love of television in all its forms, but this sudden collision between Doctor Who and early 21st century reality TV and game shows is bizarre. It works thanks to its sheer verve and the commitment of the cast, who really sell the idea of deadly gameshows, where housemates are “evicted from life” and losing contestants vapourised. On the other hand, it dates the programme more than anything else in this series; even with Big Brother and The Weakest Link still continuing in some form, this is so obviously a product of its time that it pulls you right out of the fantasy.

It moves on quickly, though, and before we know it the Doctor and Jack have both broken out, the Doctor accompanied by prospective companion Lynda-with-a-Y – an early, pre-EastEnders role for Jo Joyner. Lynda is, by all accounts, very sweet and extremely courageous, but seems mostly included to suggest that Rose won’t make it and needs a replacement lined up. Rose, on the other hand, is not coping well with general knowledge (in fairness, her knowledge is thousands of years out of date) and loses the final round against Paterson Joseph (giving a great performance, of course, but still such a shame that we never got to see him as the Doctor). Rose is vapourised by the Anne Droid, and that’s the end of that.

The Doctor has discovered that the Game Station, of which they are imprisoned, is none other than Satellite 5, a century after the events of “The Long Game.” Since he switched off the news feeds, everything has got much, much worse, with the Earth’s population now in the thrall of endless, mindless television, able to be plucked out and forced to take part at any time. It doesn’t take too long for the Doctor and Jack to find out who’s really behind the long game. The Daleks have been manipulating the Earth for centuries, abducting humans and using their biomass to grow new drones to build their ranks after the Time War. Rose isn’t dead after all – she’s been beamed to the Dalek mothership. In a storming cliffhanger, the Doctor vows to save her, shut down the Daleks’ invasion and “blow every last stinking Dalek out of the sky!”

“The Parting of the Ways” is largely an exercise in resolving all this and showing off where all the series’ budget has gone as swarms of CGI Daleks attack. It’s all genuinely visually impressive, even now, but at the heart of it there’s a strong emotional story. The Doctor is able to rescue Rose quite quickly, facing off against the Emperor of the Daleks: a huge, immobile thing that views itself as God, having survived the Time War and recreated the Dalek species from scratch. (There’s a popular fan theory that the Emperor is actually the Dalek from “Dalek,” rather than another survivor, having beamed itself away rather than self-destruct. It would certainly explain why it’s obsessed with converting humanity and why it’s so utterly nuts.)

The Doctor begins to convert the station into a weapon that will wipe out the Daleks, with the small drawback that it will take half the population of Earth with it, while Jack leads those still on the station in a hopeless stand-off against the invading forces. Davies avoids it becoming too gung-ho by focusing on the experiences of the individuals; Jo Stone-Ewings and Nisha Niyar give lovely performances as two unnamed programmers, but it’s Jo Joyner’s last moments as Lynda that really get you. While he’ll let the others sacrifice themselves for the cause, the Doctor won’t let anything happen to Rose, tricking her to go back into the TARDIS, which he has set to return her to her own time.

The episode gears up to two great climaxes. On the Powell Estate, Rose, with Mickey and Jackie’s help, wrenches open the TARDIS’ central console to release the energies within, in the hope she’ll be able to communicate with it. Instead, the energy of the Time Vortex enters Rose herself, rocketing her and the TARDIS across the millennia to the Game Station. The Doctor faces the goading Emperor, having finished his weapon but unable to bring himself to cause even more deaths; a parallel to what the decision he faced at the end of the Time War. With Rose safe and everyone else dead (including Jack), he waits for the Daleks to exterminate him… and Rose arrives, with the power of a god, wiping out the Daleks for good. (Until next year.)

While it’s another deus ex machina, it feels earned, building on elements of the series so far and Rose’s continued development from humble shop girl to space/time adventurer. Rose has become the Bad Wolf, having retroactively left clues for herself throughout history to lead her back to this point. She’s even able to bring Jack back to life (this will have consequences, but as he’s left behind, we have to wait for Torchwood to find out what they are). Unfortunately for Rose, the human brain isn’t meant to handle the total energies of time and space, and she is dying.

In the end, it’s an excuse to get the Doctor and Rose to kiss, as he draws the power into himself and then back into the TARDIS, leaving him damaged enough that he has to regenerate. It’s beautifully written, acted and shot from start to finish, even knowing exactly what’s coming. Yet it was such a missed opportunity. Davies had planned to keep Eccleston’s departure under wraps, surprising the audience with a regeneration without warning. Who knows if he’d ever have managed it, but in the event, everyone was eagerly waiting for David Tennant to appear.

In spite of their deteriorating relationship, Davies has never had anything but praise for Eccleston’s performance as the Doctor, and his final speech for him reflects that. It’s a short but sweet celebration of this brightly burning incarnation, and the incredible performance by Eccleston. If it wasn’t for his fantastic Doctor, the relaunch may never have worked, and it almost certainly wouldn’t still be going strong today. Eccleston has declined to return to the role onscreen, and seems unlikely to ever do so, but surprised everyone in 2020 with the announcement that he would return to the role on audio for Big Finish.

The first series of the revived Doctor Who is an uneven but joyfully ambitious rollercoaster that built the foundations of what the programme can achieve. Funny, silly, dramatic, heartbreaking, fantastic – Eccleston’s sole series brought Doctor Who back with a bang.