Pyramids of Mars

Reviewed by Daniel Tessier

1975 is a strong contender for Doctor Who's finest year, featuring a run of classic serials across two seasons that are repeatedly cited as among the programme's very best. The Ark in Space, Genesis of the Daleks, Terror of the Zygons and, creeping in towards the end of the year, Pyramids of Mars, perhaps the archetypal Who horror story.

Late 1975 was deep in Doctor Who's gothic phase, when Hammer Horror was a major influence on the series' stories. Hammer itself was waning in this period, producing its last few horror films before it focused on television in the 1980s. The classic period of Hammer Horror from the 1950 and 60s, however, remained fondly remembered and influential (as it still does, leading to the brand's revival in the 2000s). Pyramids of Mars draws heavily on Hammer's Mummy movies, particularly 1959's The Mummy, much of the imagery of which is almost slavishly recreated. Another significant, if less celebrated part of Hammer's classic output, was science fiction, which commonly featured horror content as well. Pyramids of Mars combines the gothic horror and Egyptiana of The Mummy and its sequels (which themselves were heavily influenced by Universal Studios' Mummy films) with the sci-fi trappings of aliens and robots.

The result is a fantastically atmospheric serial containing some of the programme's most memorable imagery and performances. Much of its success, of course, is down to its script; credited to one Stephen Harris, it was actually a submission by Lewis Griefer (Crossroads, Who-Dun-It), heavily rewritten by script editor Robert Holmes. Nonetheless, this is a serial where acting, design and direction (by Paddy Russell – Out of the Unknown, Moonstone) come together to incredible effect.

Heading back to UNIT HQ, the TARDIS is pulled off course when an unsettling, animal-like visage appears within the control room. This in itself was alarming to the Doctor and the viewer, the TARDIS being shown as virtually impregnable in this period. The idea that some villain could, by what the Doctor describes as sheer mental force, essentially poke his head in removes the idea of the Ship as a safe haven. The TARDIS arrives in the right place, but at the wrong time, materialising in 1911 in an old priory house on the future site of the HQ. The serial was filmed at Stargroves House and Estate, then owned by Mick Jagger and used primarily as a recording studio. The “Victorian Gothic folly” is the perfect location for the serial, granting it a suitably arcane atmosphere. Of course, there was a reason that both the BBC and Hammer liked setting things in Victorian and Edwardian England: they had both the locations and costumes available in abundance and could always pull them off.

The opening of the serial, however, is set briefly in Egypt, which is where the rest of the imagery comes from. The trappings of Ancient Egypt are immediately evocative and, just as importantly, easily recognisable. Once we've seen the inside of a pyramid, a sarcophagus and a big fella wrapped in bandages, we know exactly where things are heading. The addition of the extraterrestrial into this, then, is a great subversion. The idea that the Egyptian gods were alien beings and that they helped build the pyramids is straight from Chariots of the Gods, the popular work of pseudoscience and false history by Eric von Däniken. By 1975, this was seven years old, and was already well known, but its use in popular sci-fi was still unusual enough to be fresh. These days, post-Stargate and any number of similar ideas, it's not so surprising.

Still, even watched now, this just works. The haunting image that appeared in the TARDIS is the face of Sutekh, a very old name for the Egyptian god better known as Set or Seth. The relentless antagonist of Egyptian myth, Sutekh is here reimagined as the last survivor of the Osiran race, an incredibly advanced alien civilisation that fell after banding together to imprison Sutekh and stop his mission to wipe out all life in the universe. He's spent the last seven thousand years locked up in a pyramid in Egypt (controlled from Mars) and has now found a way to escape and wreak havoc. He's presented as the ultimate evil and is even linked to Satan for good measure.

The noted archaeologist Marcus Scarman has disturbed the Egyptian tomb and has fallen under Sutekh's thrall. Using a space time tunnel hidden within a sarcophagus, Scarman returns to his home in England, before setting work on the construction of a missile, aimed at Mars, which will destroy the Eye of Horus and release Sutekh from his bonds. Then, it's a simple task for Sutekh to use the space time tunnel to escape back into the outer universe, stopping to wipe out life on Earth first. Scarman is assisted by Osiran service robots – hulking androids wrapped in bandages to protect them from corrosion.

It's a brilliant combination of well-worn horror tropes with pulp science fiction, heightened to become truly mythic. It wouldn't work without the complete conviction of one of Doctor Who's best ever casts. At the centre of it all we have the Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith, played by Tom Baker and Elisabeth Sladen at the absolute top of their game. By this stage they'd completed almost two seasons together and were working as a well-oiled machine, bouncing off each other perfectly. Baker, in particular, had honed his performance, switching mercurially between gleeful enthusiasm and unnervingly alien detachment. Sladen's also at her best as Sarah, facetiously baiting the Doctor but dead serious when faced with the frightening reality of their situation.

Marcus Scarman is brilliantly realised by Bernard Archard (Spycatcher, The Legend of Robin Hood). As an already pretty stiff archaeologist, killed and reanimated as the servant of Sutekh, Scarman could have been a terribly dull role, but Archard fills him with both menace and pathos. Looking for him is his brother, Laurence, played for maximum sympathy by lovely old Michael Sheard (Grange Hill, The Outsider).

Laurence becomes something of a secondary companion for much of the story, tagging along with the Doctor and Sarah, but his refusal to give up on saving his brother leads to his inevitable demise. While Archard had appeared on the series before (in Patrick Troughton's first serial, The Power of the Daleks), this was the third of six Doctor Who roles for Sheard across more than twenty years.

There are a number of memorable secondary characters as well. Before Scarman returns to his family home, the way is paved by Ibrahim Namin, the obligatory Arabic henchman, fez and all. Peter Maycock (The Wright People) does well to make him sinister without being too stereotypical. Peter Copley (Cadfael) gives a classy turn as the wonderfully named Dr. Warlock, while Michael Bilton (Waiting for God) makes the ill-fated butler Collins a likeable chap. Then we have Ernie Clements, your classic country estate poacher, played by George Tovey (Bootsie and Snudge). Both Bilton and Tovey had Doctor Who links in the 1960s: Bilton had appeared in the William Hartnell serial The Massacre, while Tovey's daughter Roberta had played Susan in the two big screen Dalek movies.

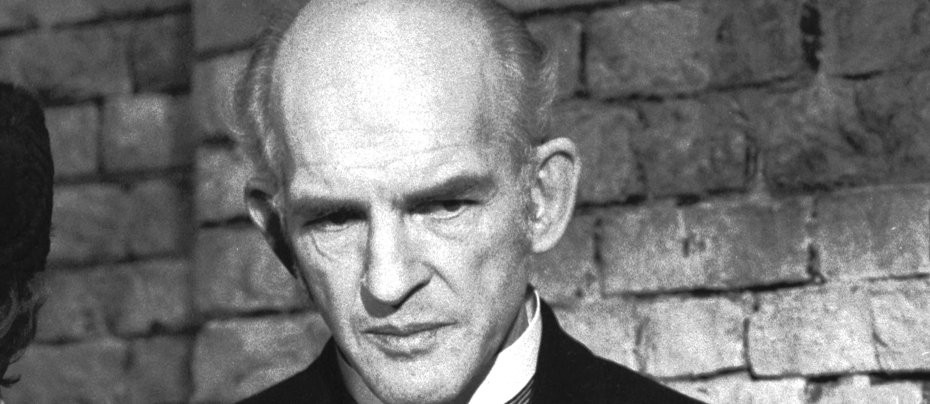

The real star turn in this serial, though, is Gabriel Woolf (Emergency-Ward 10, Knights of the Round Table). An actor with a rich radio career thanks to a deep and velvety voice, Woolf portrays Sutekh himself, both as a disembodied voice and from within an all-encompassing costume topped off by an ornate mask. It's a performance that hinges entirely on the quality of the voice, and Woolf gives an incredibly sinister turn. He's helped by some wonderfully evil lines, which for the most part he delivers in a cruel whisper that suggests barely restrained power and fury. “Where I tread, I leave nothing but dust and darkness...” is particularly hard to forget. It's an exceptional vocal performance that cements Sutekh's place among the most terrifying Doctor Who villains.

Of course, Sutekh's actions also speak for him, and Baker's performance sells the incredible power of the creature. It's rare we see the Doctor truly frightened by an adversary, and here Baker spends much of the serial as serious as we've ever seen him, moving up to real terror when he comes face-to-face with Sutekh and finds himself powerless against him. While the Doctor still has his usual flippant moments, they're fewer than we're used to, impressing on us just how huge a threat he is now facing. Perhaps the single most impactful moment comes shortly after Sarah suggests they just leave and remove themselves from harm's way. After all, they both know the world wasn't destroyed in 1911. The Doctor takes her back to the TARDIS and sets the controls for Sarah's own time, 1980 (let's not get into that), opening the doors onto a barren, howling wilderness.

It's a deeply unsettling scene, one that Russell T. Davies, upon relaunching Doctor Who in 2005, was dying to recreate. He finally did so in he 2024 episode “The Devil's Chord,” again selling the incredible threat to all life posed by the godlike villain of the story. It's a standout moment, one that subtly reconfigures the entire series' ethos. Here, the Doctor is portrayed as someone trapped by his existence as a time traveller, bound by an immense responsibility to intervene. For if he doesn't, then time could be unwritten in an instant...

While it would be tempting to call Pyramids of Mars a perfect Doctor Who story it does have its flaws. The mummies, for all they're a fine idea on paper, look a bit silly, particularly their noticeably buxom chests. One scene sees a character crushed between two of the robots, and unfortunately it doesn't come across nearly as seriously as it's meant to. There are some odd visual choices here and there, such as the time tunnel effect, which looks for all the world like the inside of a tube of Smarties. There are also the inevitable little production slip-ups, such as a notorious gaffe: when Sutekh is freed and finally stands up after millennia of stupor, a BBC technician's hand is visibly holding down his little cushion. Bless.

The final episode is a bit of a runaround after all the careful set-up of the preceding three parts. It's good to see Doctor Who finally visit Mars; the first time the Doctor actually sets foot on the planet (and not an Ice Warrior in sight). Unfortunately, it devolves into a series of rather anticlimactic puzzles, which Horus and the other Osirans decided were the best way to keep Sutekh inaccessible. Still, the final act works well, with the Doctor almost facing defeat before outsmarting Sutekh with some very quick thinking and an even quicker escape.

In spite of these flaws, Pyramids of Mars remains one of the most beloved and best remembered serials from one of Doctor Who's most successful eras, with Sutekh justly being celebrated as one of the Doctor's greatest adversaries. Despite seemingly being thoroughly dealt with at the end, Sutekh did manage to return. Woolf once again gifted Doctor Who with his voice in 2006 when he voiced the Beast in “The Satan Pit” (once again portraying a being alleged to be the Devil) before finally returning to voice Sutekh opposite Ncuti Gatwa's Doctor in 2024's “Empire of Death,” almost fifty years after his initial appearance. The latter was accompanied by a remastered version of the story, released as part of the Tales of the TARDIS spin-off series. Between these two televisual returns he voiced the Osiran menace on audio several times for Big Finish and Magic Bullet, a rare monster who loses nothing by being portrayed in a sound-only medium. Russell T. Davies's decision to twice hire Woolf for his version of Doctor Who shows just how much an impact his performance and this serial had on him. Still, perhaps not as much as his decision to intercut one of the serial's most powerful scenes with a notorious sex scene in his 1999 hit Queer as Folk. Now that's what you call a fan.