Hot Summer Night

1959 - United KingdomWarning. This article contains historical reviews using language and expressing attitudes that are now considered outdated and which some readers might find offensive. However, in order to do justice to the production and the intentions for which it was written, I feel these references are essential to capture a snapshot of the period in which it was set and, more importantly, to convey the impact it had.

The article also makes reference to 'the colour bar', an expression that was widely used during this period. The colour bar in the UK during the 1950s referred to a form of racial segregation that was prevalent in various public and private spaces, including pubs, workplaces, and other commercial premises. This discriminatory practice faced significant opposition in the 1950s and 1960s, leading to high-profile campaigns by anti-racist groups. The colour bar was not supported by any specific British laws; however, it wasn’t until the Race Relations Act of 1965 that such racial segregation was made illegal. The colour bar also extended to other areas of life, including housing and employment, where people of colour faced segregation and discrimination. It is a stark reminder of the racial inequalities that existed in the UK during that period, but does not endorse any racially outdated points of view.

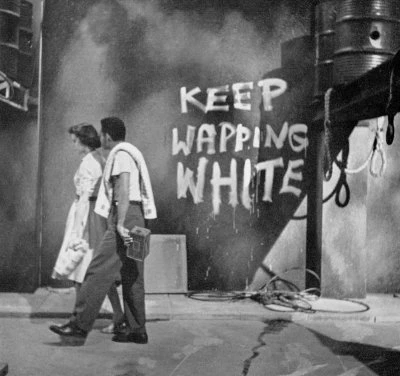

Playwright, novelist, and screenwriter Ted Willis, known for creating several television series, including the long-running police drama Dixon of Dock Green, penned Hot Summer Night for the stage. First produced in 1958, the play is set in Wapping and revolves around the Palmer family. Jack (Jacko) Palmer, a successful Trade Union leader, could easily reside in more affluent surroundings. However, his strong identification with the workers prevents him from moving to a house with a bath, as it would appear disloyal. Consequently, he fiercely advocates for the union rights of the substantial West Indian community under his care. It’s only when his daughter, Kathie, falls in love with Jamaican Sonny Lincoln that he reevaluates his stance. Meanwhile, Nell, his neglected wife, has centred her entire life around their daughter and approaches the situation with blind, hysterical prejudice.

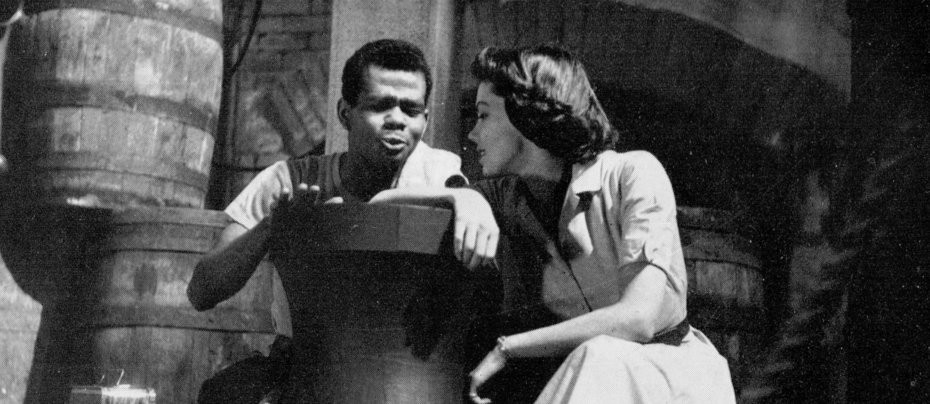

Hot Summer Night premiered at the Bournemouth Pavilion on 29 September 1958, subsequently reaching the New Theatre (now the Noël Coward Theatre) in London's West End on 26 November. It ran for 53 performances, closing on 10 January 1959. Playing the role of Sonny Lincoln was Lloyd Reckford, a Jamaican born actor who came to England in the early 1950s. He studied at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre before joining the Old Vic Company in London. In 1958, he appeared in his brother Barry’s play Flesh to a Tiger at the Royal Court, with Cleo Laine. Kathie was played by Liverpool born actress Andrée Melly, John Slater played Jack and Nell was played by Joan Miller.

The play swiftly transitioned from stage to television, undoubtedly facilitated by the vision of newly appointed producer Sydney Newman. His aim was to showcase drama on Armchair Theatre that resonated with the genuine concerns of the audience. On stage, the play had a dual focus; the neglect suffered by Nell Palmer at the hands of her husband, and the relationship between Kathie and Sonny. For television, the emphasis was repositioned, the focus shifting squarely onto the drama arising from the proposed mixed marriage.

Lloyd Beckford later said that he couldn't remember any flak over the play's controversial inter-racial relationship. "But I can remember one incident which occurred during one of the Saturday matinee performances in London," he recalled. "It was rather pathetic. It was during the scene when I kiss Andrée Melly. A frail, rather timid and very gentle voice called out from the stalls - 'I don't like to see white girls kissing niggers.' There was dead silence in the theatre, and we went on with the play. That was the only incident, but, of course, the newspapers made a big deal of it. There was a full page picture and headline saying ‘First time on London stage, black man kisses white girl’, that sort of nonsense. But I didn’t mind – it gave me a little bit of publicity!”

The kiss was, of course, kept in for the 90-minute television adaptation and as well as being one of the first television dramas to tackle issues of race, it was also the first time an inter-racial kiss was seen on television. The director of both versions was Canadian born Ted Kotcheff who had only arrived in Britain in 1957, invited by Sydney Newman who had been the Director of Drama at CBC in Toronto where they worked together. The West End cast was retained for television, with the exception of Joan Miller, whose role was taken by Ruth Dunning, the Welsh actress who had found television fame in 1954 as Gladys Grove in the BBC soap opera The Grove Family. There was three weeks between the stage play finishing and the television production’s broadcast.

After that broadcast, the critics honed their pens – most of them grasping the core issues of racial integration and community double standards such as Jacko, a staunch union supporter, unmasked as a hypocrite—championing colour equality at work but opposing mixed relationships at home, Nell’s visceral disgust at the idea of black and white skin mixing being laid bare, meanwhile, Sonny grappling with ‘shame’ over his skin, yearning only to marry the girl he loves.

Derek Hoddinott, writing in the stage said: I had the advantage of not seeing the West End production of Ted Willis' "Hot Summer Night" televised last Sunday in the Armchair Theatre series. I viewed it as a piece of television and nothing else. What I saw I liked very much.

Strange to say I found myself unmoved though I could appreciate the plight a mother might be put into if a daughter announced her intentions of marrying a coloured man. This is the problem Ted Willis poses. Mixed marriage. Do they or don't they work? Only a sequel will reveal the answer because Mr. Willis doesn't attempt to solve the problem in this play. He just shows us individual reactions to it and that's enough to ask of any author.

The production of William Kotcheff was shot mostly in close-up giving greater emphasis to black and white. Witness the dialogue between Jacko and Sonny. Cutting from one to another brought out the real dangers of black versus white. Witness the close up of Kathie holding hands with Sonny. This would have been lost on the stage, but on television it heightened the effect. Witness the close-up of Sonny's big black hands. "A barrier of hands" he cries out. This brought viewers even closer to the problem the play was raising.

Acted well by a strong cast headed by John Slater as the union leader, Andree Melley as his daughter, Lloyd Reckord as Sonny, and Harold Scott as the Old Man, the real bouquet must go to Ruth Dunning who gave a really heart rending, yet beautifully controlled performance as the tortured mother. It is about time this talented actress got rid of the Mrs. Grove tag. She did it once and for all last Sunday.

Reviewed by Philip Purser in the (London) Daily News, he observed: By West End standards Ted Willis' "Hot Summer Night" was rated an uncommonly realistic play. By television standards it seemed pretty theatrical.

Maybe this was exacerbated by William Kotcheff's hammer-blow punctuation of the piece in his production for Armchair Theatre last night.

The hands of the young lovers clasped in giant close up, black and white. Bursts of pregnant music underlined the long-drawn-out stares with which Mum (Ruth Dunning) greeted each revelation.

British understatement and evasion can be a bore, I admit, but no play set among the British can defy these qualities. The impression here was sometimes of an American waterfront drama-Miller, perhaps, or Schulberg - miraculously transplanted to London's East End.

That, of course, is partly a compliment. "Hot Summer Night" is a fine play with the guts and directness of the American theatre. It bangs its characters—the white ones-anyway—up against their prejudices like crates stacked against a wall. It presents, in Jacko, the union official and troubled father, a profound picture of a big, puzzled, violent man, brilliantly played by John Slater. It has something valuable to say and says it well. A.B.C. are to be commended for dramatically extending its audience after a disappointingly short run in the theatre.

And Bill Rogers in the Liverpool Echo wrote: It would have been easy, oh - so terribly easy for Ted Willis to bow to the box office and give "Hot Summer Night" a tidy, everything-in-the-garden-is-lovely ending. Instead, he chose to give us a play to remember, and last night ITV matched the gesture with a sensitive, imaginative production.

On the face of it, Ted Willis's subject was the colour bar. But essentially, he was debating one of those nagging dilemmas that have troubled us long before mixed-marriages posed problems. It's all very well to generalise airily on prejudice where other people are concerned. But what happens when the problem comes knocking at your own front door? In "Hot Summer Night," a champion of equality finds himself ducking behind uncomfortable arguments when his daughter wants to marry a coloured man. And the problem refuses to be resolved into a neat, logical equation.

Exploring the situation with humanity and intelligence, Willis invests his characters with dignity. And last night's cast—John Slater and Ruth Dunning in particular—gave performances as fine as any we're likely to see for a long, long time.

The play was subsequently adapted into the feature film Flame in the Street (1961). In this cinematic version, the narrative expanded to include a broader perspective, incorporating more scenes from the workplace and the local community.

Although Hot Summer Night doesn’t offer definitive solutions, its conclusion carries a faint glimmer of optimism. Kathie and Sonny remain resolute in their commitment to marry, even in the face of anticipated prejudice and societal challenges. However, it contributed to altering perceptions by portraying racial tensions, family dynamics, and societal biases, its impact resonated beyond its era, laying the groundwork for future transformations in attitudes and roles.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 28th, 2024. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.