Rainbow City

1967 - United KingdomThis review of an important and ground-breaking television series contains some views and article quotations which uses contemporary language and opinions from the year it was produced (1967) as well as later interviews with members of the cast, the series creator, and the series writer. As a result, some terms used might be considered unacceptable to a modern-day reader, but to accurately follow the series’ development, its social impact and the history of people of colour as depicted on British television, I have deemed it necessary to reproduce these references as originally stated.

Laurence Marcus 29/06/2022

Rainbow City was conceived by John Elliot who began his television career at the BBC in 1949. Having served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in Europe, the Middle East, and South East Asia, Elliot, a confirmed pacifist, had used his experiences to make the first ever documentary series that the Corporation made, a fifteen-and-a-half hour series on the Second World War. As a result, he was seconded to the United Nations in New York by the BBC. In 1956 he returned to the UK by way of the Bahamas where he discovered an ‘extraordinary subculture.’

“The Bahamas had been British on the map for a long time, and it had bred a native population which believed in the myth of pre-war Britain,” he told the Channel 4 documentary Black and White in Colour (1992), a series that explored people of colour in British television since 1936. “There was this colonial way of life going on, which seemed like something out of an Edwardian storybook. There was this extraordinary, simple faith in England which I knew was an old, tired, grey and corrupt idea, but which the people from the West Indies were looking to as a sort of Nirvana. I thought that the clash between this mythical Britain and the actual grotty real Britain, which West Indians would face when they got here, was a terribly important and exciting conflict.” With the concept of a drama forming in his head, Elliot spent the summer of 1956 researching in Brixton and other parts of London where there were West Indian populations. The result was a single play, A Man from the Sun, which explored the harsh realities of life for the first Caribbean settlers in the UK.

Elliot wrote in the Radio Times magazine in November 1956: ‘This is not another programme about the colour-bar, race prejudice is one of the problems with which it is concerned: others are work, housing, and the social adjustments which we and our new neighbours must be prepared to make if we are to live happily together.’

Up until A Man from the Sun there had been very little on television about race relations. “It wasn’t a major issue then,” said Elliot, “except for people who had extreme views on one side or the other. To that extant it was controversial, but the BBC seemed less worried about controversy in those days.”

After A Man from the Sun, Elliot went on to write and produce other programmes for the BBC. His best known creations included A for Andromeda and The Andromeda Breakthrough which he co-wrote with Sir Fred Hoyle, the long running drama series The Troubleshooters and the historical drama series Fall of Eagles which he co-wrote with his wife.

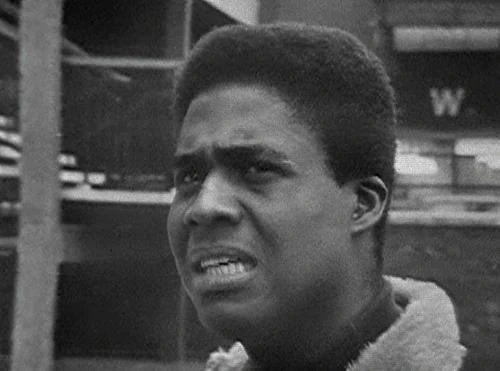

Ten years after the broadcast of A Man from the Sun, Elliot was approached by the Head of Programmes for BBC Birmingham to do a series of programmes about West Indians living in Britain. “There was a strong feeling at that time, that West Indians should be given the chance to be treated as people. By that, I mean as people whose possibilities and talents were much greater than they had been allowed to show.” Said Elliot. “And so, with Errol John playing our chief character, we made him a professional man, a lawyer with a white wife (played by Gemma Jones), living in a racially mixed community in Britain.” It was the first time that an interracial marriage had been shown on television, but it was not the first time that an interracial relationship had been depicted.

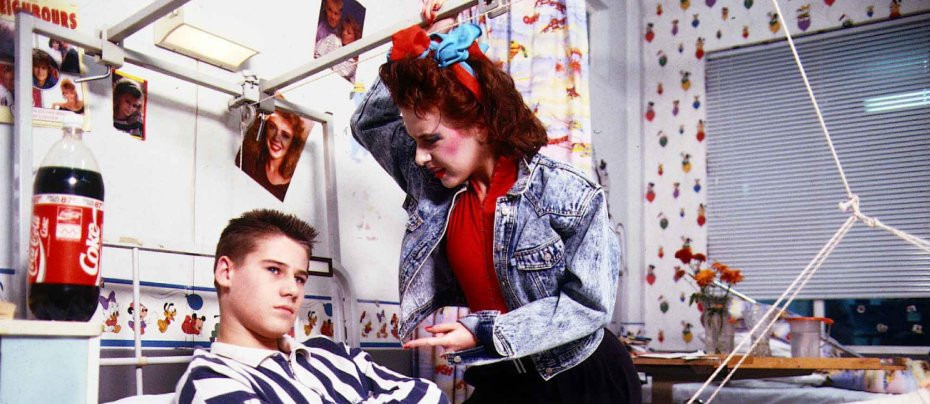

In 1964, the popular medical drama Emergency Ward-10 had run a story about an African female house-doctor, played by Joan Hooley, who has a love affair with one of the doctors (actor John White) at the hospital. “There was a scene where we were supposed to kiss in a bedroom.” Remembered Hooley. “The papers got hold of it and all the objections started to be raised. It was suggested that the kiss would be unfit for viewing at 7.30 in the evening, because young people may be watching. The ITV authorities banded about for several weeks. John White and I had great fun speculating on what they were going to do next. Well, we never did get our kiss in the bedroom, instead we ended up kissing in the garden quite sedately.” The romance didn’t last though and shortly after that scene Hooley was written out of the series. “It was quite funny actually. The fuss the papers made about the kiss with headlines like ‘First black and white television kiss.’ And, of course, all the time I was married to a white man!”

Rainbow City was first mentioned in the press on 23 February 1967 when The Stage reported: ‘BBC's Midland Region have produced three episodes of a series written by John Elliot about the problem of a Jamaican living in Birmingham. The series is called "Rainbow City". The episodes are a "pilot" version, soon to be submitted to BBC-l's Controller, Michael Peacock. It tells the story of a Jamaican and his white wife, in Birmingham. "The series poses the questions 'Why do Jamaicans come here, and how do they get on?'," says a BBC spokesman. "It does not preach, and it is not a documentary."

By March the possibility of a prime-time BBC1 slot was gaining ground as, once again, was reported by The Stage: ‘Midland region have put forward the three pilot episodes for networking on BBC-1 and BBC executives at Television Centre have looked at them. A decision on whether the new serial will be shown on BBC-1 will be made soon. If it is not to be shown on BBC-1, then Midland Region may show it in the Birmingham area. While the actual appeal and practicability of "Rainbow City" has yet to be proved, the serial does offer the opportunity to deal with an important topical problem, the successful integration of West Indians into a large industrial city like Birmingham. It could show West Indians simply as people. Few productions have done this as yet; most introduce coloured people only when their presence is significant to the plot. Such a serial could be entertaining, sophisticated, down-to-earth, harsh, humorous, sad. But it should not try to preach; its point of view should be implicit, never crudely explicit. The faint-hearted or the basically uncreative are always saying, "It's easy to have good ideas, they are ten a penny. It's making them work that's the problem". The BBC's drama department does not shirk difficult issues in its Wednesday Play and consequently produces plays like "Cathy Come Home" which attract millions and make people aware of our social problems. Nothing can guarantee a programme's success and an exciting challenge like "Rainbow City" brings with it many problems. But taking up exciting challenges is the best way to make exciting and worthwhile television.’

By April the BBC had made their decision and three more shows were added to the ‘pilots’ – The Stage: ‘Three pilot episodes were shown to Michael Peacock. BBC-l's Controller of Programmes, and Sidney Newman, head of BBC drama, who accepted them for networking and asked for three more to be produced.’

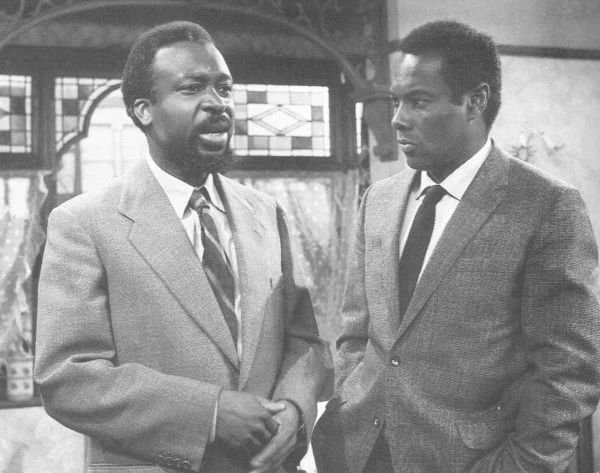

Previewing the series in the Radio Times David Porter, Head of Programmes in the BBC's Midland Region, which at that time was already transmitting programmes in Urdu and Hindi for Asian residents, spoke about the lead character, John Steele who was played by Errol John, a Trinidad and Tobago born playwright and actor who emigrated to the United Kingdom in 1951. ‘He is much like any other family solicitor, although he happens to be Jamaican, and the people who come to him-mainly other immigrants-have the same recognisable egos and psyches, hope and fears, and difficulties as the rest of us, plus a few problems of our own. These are the bases of our story. I've never had the least doubt about this serial - mainly, I think, because I've known that there are West Indian actors, writers and musicians in this country who can lift it right up. Normally, they have little chance of sustained, serious work.’

The first episode of Rainbow City went out on Wednesday 5 July 1967 at 7.30pm. The following day, the press reviewed the show with mixed reactions. The Daily Mirror said, ‘BBC-I's " Rainbow City," the first of a six part series, packed in the lot last night. It took the wrappers off something we associate with Birmingham, Alabama and plonked the whole scene in bustling Birmingham, England. There were fast, telling opening shots: a West Indian woman stooping over the shopping basket which jeering whites had knocked from her grasp; a West Indian singing his heart out in a white congregation...equal before God but only in church.

In the market place, a push, an alley fight, a vengeful knife - and a Jamaican who left home to find fame and fortune, died.

Why do they come?

"They are the victims of illusion," said one character. Why do they stay? "They want to belong". They come to find work and find hate."

It's gripping and grim, it's got plot, characters, pace.’

The Stage took a different view: ‘In last night's episode, filmed against a city centre background. an 18-year-old Jamaican boy attempted to beat up a couple of white youths who had insulted and tripped up his uncle in the Bull Ring market. In the fight the boy was fatally injured. The lawyer, helping the family, looked into the boy's background, which involved talking to the vicar, the youth club leader, the former school teacher and the boy's foreman at a Birmingham factory. The episode ended with the lawyer in Jamaica on his way to visit the mother who was hoping to send her second son to Britain. Colour prejudice and the unrealistic hopes which many immigrants have of Britain were among the topics raised by the play. Coloured nurses, youth leader, teacher and a high proportion of coloured men and women among the Bull Ring crowds underlined the point that immigrants are now part of life in Britain. The characters were shown as people rather than white or coloured people.

The lawyer's intelligent wife contrasted with the vapid English vicar, the church-going Jamaican uncle with the dead boy, troublesome son of a troublesome father. Apart from the novelty of the setting as a play, ‘Rainbow City’ was slow. Substitute class difficulties for colour difficulties and this was a familiar plot. The play was written by John Elliott and Horace James. Mr. James defended the programme on BBC-1s ‘Late Night Line Up’ last night. On the programme it was stated that a number of calls had been received by the BBC, objecting to the use of the subject of West Indians in Birmingham for a television series. Mr. James said: "When one sees a programme like ‘Rainbow City’ with negroes, one is tempted to understand more readily that these are people just trying to live. Here is a story—you like it for its entertainment value, or you don't. "I am sure one or two people will change their views about the way people live in Birmingham."

A later episode, reviewed by Ann Purser in The Stage, didn’t consider that the series had improved or tried hard enough to get its message across: ‘Errol John plays John Steele, the solicitor whose partnership in the firm is an astute piece of assessment of the population make-up of this particular city. His clients come from Trinidad or Barbados, but he preserves a very English dignity throughout. So anxious does he seem to be to show how intelligent and responsible he is, that his performance dries up on an arid bed of respectability. Last week's episode was concerned with a young coloured wife (Carmen Munroe) whose marriage was rocky enough to send her to Dennis Jackson (Horace James), a suspicious kind of black friend to all black men, and then on to John Steele. He seemed fairly puzzled by it all, as I was, and his role turned out to be nothing more than a welfare officer with a rudimentary knowledge of divorce law. So it isn't a serial about the law, and it isn't a serial about a mixed marriage (so they say). It must then be an attempt at a good story about interesting people.

But the heavily loaded subject imposes itself too obtrusively on the story, and the result is a bit too solidly worthy to escape overbalancing sometimes into boring sermonising. All situations shown are in a way cliches - we know them all, and the attitudes so fairly illustrated are ones with which we are all familiar. Perhaps if John Steele were a more interesting human being, if his wife Mary were a little less saintly about returning to a country with a predominantly black population, if all the evidence weren't given so painstakingly for all sides, the programme might spark into life. I might even see the shot of Steele and his wife in bed together without thinking 'Ah yes, that's to test how you would feel if your daughter married a black man.’

Was the problem that not enough research had gone into the programme? Not according to John Elliot. “I didn’t have to do all the research, or even the writing by myself – because I wrote it together with Horace James, a splendid, ebullient actor and writer, who had an inside view of something which I can only see from the outside.

“We wrote six scripts together but, in rehearsals, he never stuck to them. He was a marvellous ad-libber. The play was enriched by Horace’s way of talking, by the way he looked at things, and by the way he handled situations in life.”

The positive representation of people of colour on British television was taking baby steps towards a more enlightened attitude in the mid 60s, although it still had a mountain to climb, but that was all to change very rapidly towards the end of the decade. Cy Grant, the Guyana born actor who also appeared on television as a calypso singer on the popular BBC programme Tonight, has vivid memories of the change. “I was young, I was happy, I was not politically aware, and racism was not at the top of my agenda then.” Then in 1968 Enoch Powell made his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech and a new tide of racism overtook the country. “It started to affect the quality of my life very much. People became overtly racist. I would occasionally get a decent role to play, but I didn’t get much of a choice. If we had a choice of what plays to do on television everything would be okay for black actors. In the end I said ‘no, I’m not going to play certain roles. I’m not going to be in Love Thy Neighbour. I’m not going to deal with that kind of crap.’”

John Elliot summed up how he felt about the progression of black writers at that time: “I began to feel that it was time that black writers were encouraged to write their own scripts, and not by people like me who were in-house scriptwriters. Horace James made a start but then he went off to Trinidad and we lost him. I don’t know how much of that ground has been covered in British broadcasting since.”

Further reading: Black and White in Colour – Black People in British Television Since 1936 from BFI Publishing ISBN 0-85170-329-1

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 29th, 2022. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.