Second Verdict

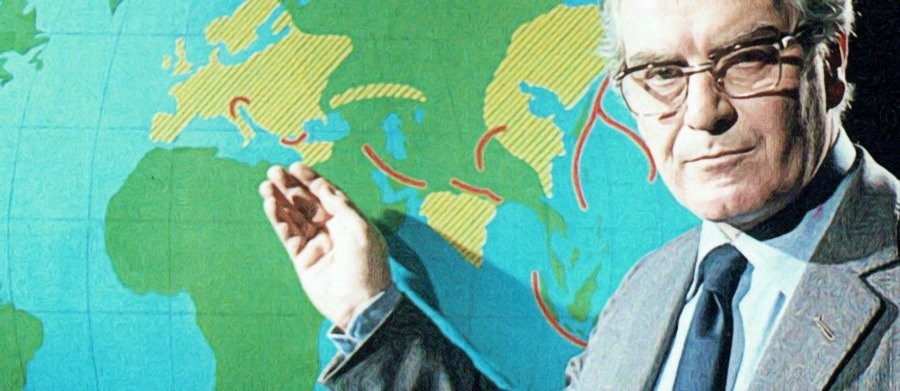

1976 - United KingdomHaving teamed two of television’s top fictional detectives in the docudrama Jack the Ripper in 1973, the BBC decided to expand on the series and let them make further investigations, this time to reconsider the verdicts of famous real-life murder trials or uncover clues to unexplained mysteries. The resulting series, Second Verdict, was not received very well at all by critics or the watching public.

Stratford Johns who had become a household name as Inspector Barlow, a no-nonsense policeman who was not averse to pounding his suspects into submission, and Frank Windsor as his gentler sidekick John Watt, proved to be such a successful collaboration as part of a much larger team in Z Cars, that they were spun-off into their own series in 1966 titled Softly, Softly.

The two senior police officers were parted in 1971 after Johns was ‘headhunted’ to take a post at Whitehall in Barlow at Large but reunited again for the Ripper series which won favourable critical admiration. The Stage critic Laurence Moody was particularly impressed with the way Jack the Ripper started, praising Elwyn Jones and John Lloyd who, in his opinion, 'very cleverly judged the right tone' for their series 'by using two fictional characters' to clinically (in modern terms) point out the way events were treated at the time of the murders. 'Stratford Johns and Frank Windsor were effective and convincing.'

Although many viewers were ultimately left somewhat disappointed by Ripper's denouement, which failed to offer any closure, a few years later the BBC were more than willing to commission Jones and Lloyd for another six-parter in a similar vein. So, after three years apart, Barlow and Watt returned as crimebusters in Second Verdict.

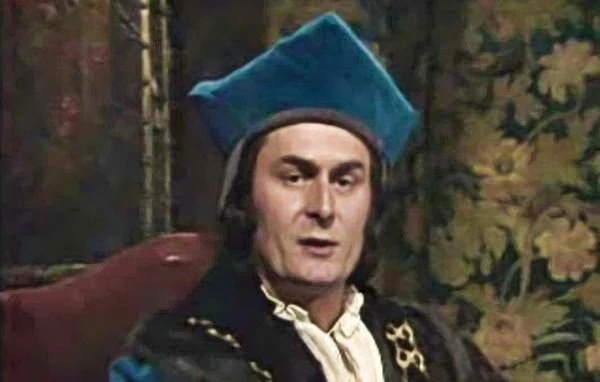

Six real-life cases came under the fictional detective’s scrutiny, including, the mystery of the Princes in the Tower in 1483. After looking at historical evidence about Richard lll, Barlow is certain that Richard did not murder the boy Princes. Watt is not so easily convinced, but Barlow presents evidence, starting with, we are told 'a survey of the crime scene' and going on to examine 'documentary evidence that has possibly been doctored.'

As history is unclear what happened to the boys after the last recorded sighting of them in the Tower, it is generally assumed that they were murdered; a common hypothesis is that they were killed by Richard in an attempt to secure his hold on the throne. But apart from their disappearance, the only evidence is circumstantial.

Having attempted to prove the impossible with this particular ‘cold-case,’ Barlow and Watt went on to investigate French serial killer Henri Landru, who murdered at least seven women but whose true number of victims, whose remains were never found, was almost certainly higher. Next was John Alexander Dickman - an Englishman hanged for murder in 1910.

Marinus van der Lubbe - a Dutch communist who was tried, convicted, and executed by the Nazis for setting fire to the German Reichstag building on 27 February 1933, came under the detective's microscope next and other series subjects were Bruno Hauptmann - a carpenter who was convicted of the abduction and murder of the 20-month-old son of aviator Charles Lindbergh, and Lizzie Borden - the woman who was accused of the murder of her father and stepmother in 1892. In the narrative of this story Watt had visited the Fall River area of Massachussetts, been to the Borden house and seen the remaining pieces of trial evidence. He and Barlow considered how a trial verdict can be swayed by errors and omissions by one side and skill and cunning on the other. Watt had one theory on how the murders were committed - Barlow had another.

The premise of the series was an interesting one, the execution however, was what the critics disliked.

The Aberdeen Evening News on 12 June 1976 complained that it was 'sad to see Barlow and Watt - once the proud heads of Softly, Softly - shunted away into a make-believe corner of television drama.' It bemoaned the fact that the former hard-nosed copper, Charlie Barlow was far too mellow while John Watt was 'sitting in the background like one of those toy dogs in the back of cars,' and that even the presence of two of crime fiction's most admired detectives failed to 'engender life into the series.'

James Scott, writing in The Stage was even more scathing and went into length about his dislike for the series:

‘Since they first made their appearance before the nation's startled gaze in the original Z Cars back in 1962, television cops Barlow and Watt, portrayed by Stratford Johns and Frank Windsor, together or singly, in a variety of settings from working-class Newtown to Whitehall's corridors of power, have bullied and snarled their way to a solution in hundreds of cases of fictional crime, and brought hordes of make-believe villains to justice. They have earned their places in the television pantheon. They should have been content.

But no, here they are, together again, equal in rank now, both are Detective Chief Supers, looking sleek and prosperous and sounding insufferably smug, spending a relatively quiet, if somewhat gad-about summer reinvestigating real life mysteries in a six-part series called Second Verdict, produced in BBC Birmingham by Leonard Lewis and Lawrence Gordon Clark.

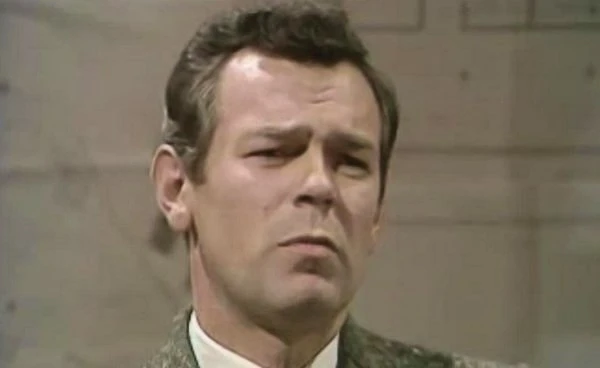

Murder On The 10.27 (BBC l, Thursday. June 17, 9.25pm) written by John Lloyd, was the fourth case in the series and dealt with a murder committed in the Newcastle area on Grand National Day in the year 1910, for which one, John Alexander Dickman (Ralph Watson), was tried, convicted and executed.

Barlow thought him guilty; justice had been done, although it could not be seen to have been done. Watt thought differently and argued, with some cogency, the existence of reasonable doubt. The arrest, the identification of the accused, his subsequent trial and conviction were, opined John, a farce from start to finish. A recital of the facts and some well-mounted, cleverly acted reconstructions of parts of the trial, seemed to support Watt's arguments.

Right at the end John Watt gave us a real jolt. Dickman may not, after all, have been hanged for the murder of the clerk Nisbet on the 10.27 from Newcastle in 1910, but in revenge for the unsolved murder of a woman in the South of England in 1908, a woman whose husband had friends in high places!

In other words the Establishment "knew" Dickman had committed the first murder but could not prove it in court. They were "out to get" Dickman and the circumstances of the second murder provided them with the means. A somewhat startling theory for which, in the way of such theories, there is now no supporting evidence, all relevant documents having vanished.

Directed by Gilchrist Calder and with some excellent character studies from William Fox, Mark Dignam, Patrick Barr, Hugh Manning and John Humphry, Murder on the 10.27 told an interesting story and was arguably the best of the series thus far.

Despite the variety and interest of the material which ranges widely in both time and place, one episode going all the way back to the fifteenth century to re-examine the mystery of the Princes in the Tower, another visiting America to look at the Lindbergh kidnapping, the basic idea of real criminal cases presented and analysed by two totally imaginary sleuths doesn't seem to me to work terribly well.

In productions in which there is an infuriating insistence on thrusting Barlow and Watt to the forefront of the viewer's attention with too frequent cuts from re-enactment of the real drama to yet another shot of Charlie or John registering surprise, anger, puzzlement and, rather too often in Charlie's case, self-satisfaction, Stratford Johns and Frank Windsor are in some danger of letting the characters they created become a rather comical double-act, the Abbott and Costello of the law.’

Using two fictional detectives to study real-life cases could have been an inventive way to interest viewers in the mysteries of real-life cases. Unfortunately, for most critics it was deemed as nothing more than a drama gimmick that just didn’t pay off, and their unanimous verdict on the series was, ‘guilty of a missed opportunity.’

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 21st, 2022. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.