The Brontës of Haworth

1973 - United KingdomThe role of women in English literature before the 19th Century was usually to provide Objects of Desire for male protagonists. It was Jane Austen who really established them as interesting protagonists in their own right with their own points of view. Jane's heroines were sensible girls who ultimately ended up with sensible chaps. Although they might have flighty sisters by way of contrast, or even slightly flighty traits themselves at first, they understood the value of a stable income.

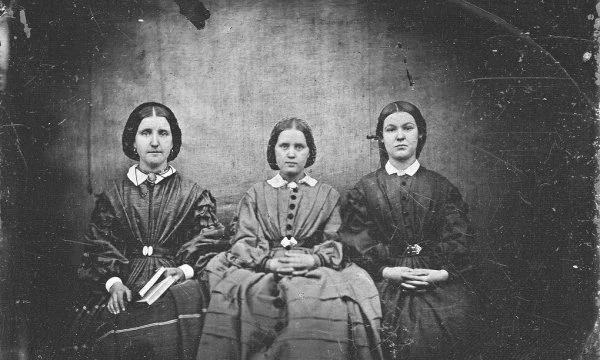

It was the Brontë Sisters who went a step further and gave the female protagonist passion, the sort of uncontrollable, irrational passion that Lord Byron had given his male heroes. They were very unlikely revolutionaries, the spinster daughters of a clergyman, the Reverend Patrick Brontë, Perpetual Curate of Haworth in Yorkshire. Haworth had been one of the birthplaces of the English Evangelical movement, with which the Reverend Brontë himself was associated. He was a staunch Tory, as were his daughters - Charlotte in particular seems to have had a curious teenage crush on a Byronic fantasy version of the Duke of Wellington. Yet, if Jane had been the good girl who had won the approval of Sir Walter Scott (he tried to copy her style in one of his less successful novels), Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë were the naughty ones at the back who were secretly reading Byron.

At a time when Austen and Scott had only just made the novel acceptable by making it morally improving - vice duly punished and virtue rewarded - the Brontës' tales of forbidden desire with downbeat endings were the equivalent of soft pornography. No wonder the respectable daughters of a very respectable clergyman had to publish under male pseudonyms.

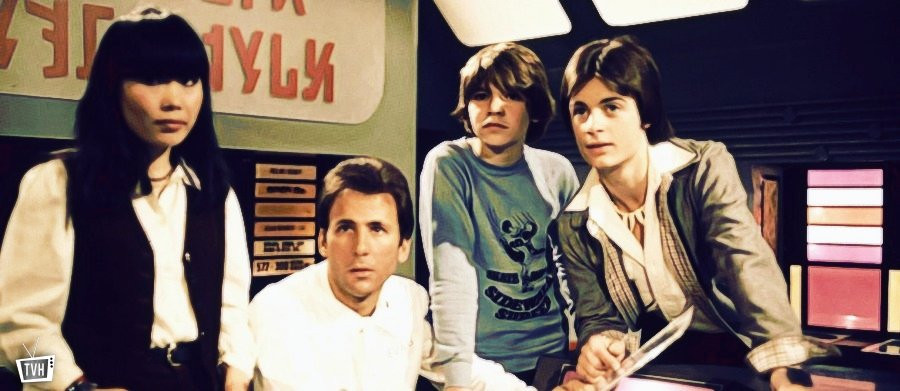

In 1971, Yorkshire Television, an ITV franchise, produced The Brontës of Haworth as a prestige project, a five-part drama, based on the lives of Yorkshire's most significant literary exports. At that point the BBC were beginning to build their global reputation for historical drama but ITV were competing strongly in the genre, investing heavily in top writers and production values that were often superior to the Beeb's. The Brontës of Haworth is very much a case in point.

Yorkshire set their ambitions high by commissioning the distinguished dramatist Christopher Fry (The Lady's Not for Burning) to write the script. He had already demonstrated his understanding of the material in an acclaimed adaptation of Anne Brontë's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall for the BBC.

Playwrights often have difficulty translating to the medium of television. Overall, the record of big names in the theatre on both the big and small screens is disappointing. The close intimacy between player and audience in a live performance is lost in mass media, and the drama can seem distant and forced if more effort is not put into realism. Fry's take on the Brontës is a glorious exception. While there are scenes that come across as a little stagey, Fry does four things that more recent scriptwriters would do well to emulate.

First, he sticks close to established facts. Where there is uncertainty about those facts, his speculation is credible. He avoids sensationalism. The emotional impact on the viewer is increased by the assurance that everything we are watching is true or at least could be true. There is no need to suspend our disbelief.

Second, having established that he has done his research, he does not show off about it. He is subtle. Important points, like the Reverend Brontë's own literary aspirations, and the fact that he is a self-made man who rose in social class - at a time when that was both more important and more difficult than today - by a combination of hard work and marrying above himself, are conveyed only in passing. Fry has a playwright's attention to detail and the courage to demand the same of his audience even on television. We are obliged to concentrate and think about what we are seeing in order to work things out for ourselves.

Third, his characters are always true to their time and place. The Brontë Sisters were in many ways proto-feminists, but they would never have thought of themselves that way. They accepted the constraints of their culture, even if they sometimes expressed frustration. Fry is right to avoid putting anachronistic words in their mouths.

Finally, he does not beat his audience over the head when he wants to make a point. The Sisters' "daily perambulation" did not usually involve them striding across windswept Moors in approved Hollywood style but rather them walking, hand in hand, in circles around their room. It says more about the frustrating lives of middle-class women in Mid-Victorian Britain than any long impassioned speech.

Fry's meticulous literary craftsmanship is essential because, to be honest, not much happens in The Brontës of Haworth. While there are many famous exceptions, like Cervantes, Defoe, Dumas, Wallace, Churchill, and Hemingway, professional writers are generally the sort of people who spend a lot of time on their own, reading, thinking, and scribbling away for long hours. They are born, they grow up, they experience the usual family incidents and friendships, they may travel a bit, they write a lot, they get rejections, they get published, and they die - not necessarily in that order. They tend to have more interesting interior lives than eventful public lives. This does not make for good drama, even if it does not discourage literary biography, a genre noted for its multiplicity of thick volumes. The novelist Elizabeth Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Brontë is the source of much of the Brontë legend as it has come down to us. Mrs Gaskell turns up as the voice over narrator, and later in person as a character, in The Brontës of Haworth, which is accurate in portraying her as a late acquaintance rather than as a close friend of Charlotte.

Leaving a lot out that might challenge Victorian respectability, Mrs Gaskell presents us with the image of a very tight knit family, the children taking refuge in imaginary worlds after the deaths of their mother and two older sisters. They become very sensitive and ill-equipped to deal with the actual world outside their cosy family home in the Haworth Parsonage.

The Sisters would, in any case, have led very restricted lives. As a Perpetual Curate, as opposed to a Rector or Vicar, the Reverend Brontë was at the lowest rank of Incumbent in the Church of England, and it had been an effort for a man without hereditary connections to get that far. He would rise no higher. Although the family lived comfortably, they had little actual cash. With no suspicion that he was destined to outlive them all, Patrick Brontë's children would have grown up in the knowledge that they would be homeless and penniless when he died. Lacking proper dowries, the girls had little hope of a decent marriage within their social class and to marry below it was unthinkable. Still unmarried in their late twenties, it seemed all three were doomed to permanent spinsterhood with no means of support. The only accepted ways for a woman with any claim to gentility to earn money were as a school teacher or as a "governess," a tutor and childminder in a private home with an ambiguous status - not officially a servant but often in practice little better, a point made subtly in The Brontës of Haworth by a bell in Anne's bedroom when she is employed in that capacity. Longing to escape that fate, the Brontë Sisters tried to set up a school of their own. That was the great enterprise of their lives and it failed miserably. Their belated commercial success as novelists came as a complete surprise: they actually expected to have to contribute financially to the publication of their works.

Fry uses this to maintain a sense of urgency beneath what seems to be, on the surface, a very sedate tale of normal family life. Great dramatist that he is, he knows how to get maximum dramatic tension out of everyday situations.

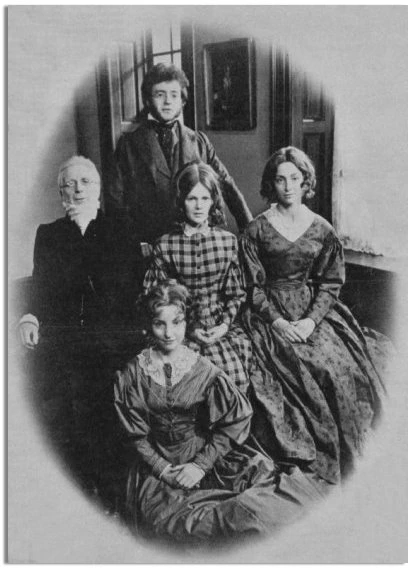

He is helped by a very strong cast, even if it was not a particularly distinguished one. Some effort seems to have gone in to finding actors who looked like their historical counterparts.

Top of the bill is Alfred Burke, a fine actor who deserves to be better remembered and who was at that point best known as the down at heel private detective Frank Marker in the long running Public Eye. Burke was always eager to demonstrate his versatility, and as the County Down born Reverend Brontë he assumes a credible Northern Ireland accent. He also bears a strong resemblance to the actual Brontë, who, in turn, did indeed, as the script mentions, bear a curious resemblance to the Duke of Wellington. Let psychologists make of that what they will.

Although Charlotte is the closest the family ensemble has to a protagonist, it is the Reverend Brontë who dominates. He is the first character we see and, tragically, the last we hear. He is probably closer to the reality of most Victorian fathers than the modern cliche. He is stern, disciplined, authoritative, and slightly pompous, but also likeable, humorous, and caring. He loves his children and is, if anything, a little too indulgent, especially of his scapegrace son, Branwell.

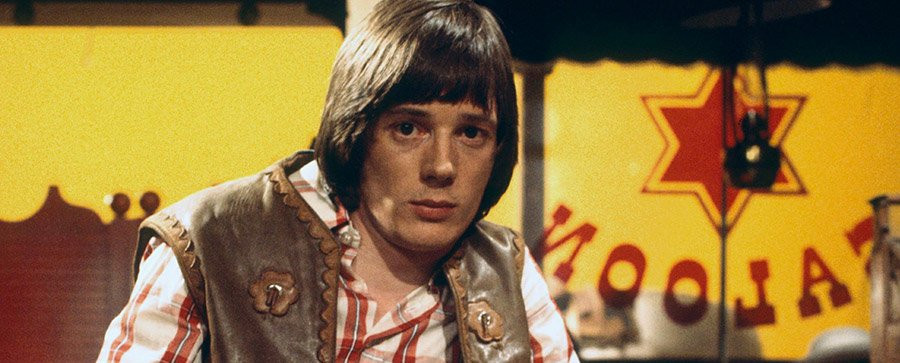

If the young Michael Kitchen sometimes seems to overact as Branwell, it has to be said that Branwell himself seems to have been that sort of character. As the only son of the family, he was the repository of all its hopes, and he was not without potential - perhaps it would have been better if he had been. As it was, everyone telling him how clever he was seems to have gone to his head. He became extremely boastful, not realising that he was not as talented as he assumed and that even talent requires that one still does the actual work. Failing in everything, he fell victim to the then fashionable cult of sensibility, sinking into self-pity on the assumption that he was simply too delicate for the world. Alcoholism and drug addiction did not help. Nor did the cosmic joke that, contrary to the assumptions of the family and the general expectations of the time, it was his sisters who turned out to be the really talented ones and who put in the hours necessary for success while he was busy posing as the misunderstood tragic hero.

It is to Kitchen's credit that one cannot help feeling sorry for Branwell, if not quite as sorry as he apparently felt for himself. One sees his modern equivalent all around.

The Sisters are at first very much under his shadow and it is difficult to tell them apart. This is perhaps deliberate. Only gradually do their separate characters emerge. Emily (Rosemary McHale) is high strung but at the same time strong minded and practical, very much a Yorkshire lass, and kind. Charlotte (Vickery Turner) seems more sensible, the sort of heroine of whom Jane Austen would approve, but is actually prone to intense obsessions. Anne (Ann Penfold) is the still water that runs very deep.

There is a definite air of sexual frustration about them, which famously finds vent in their writings. Fry's great achievement is to keep this understated. No scriptwriter would be allowed to get away with that now.

Benjamin Whitrow is an out of his depth Curate with a crush on Charlotte. Barbara Leigh-Hunt is Mrs Gaskell. Oliver Ford Davies is Branwell's friend, the Bradford painter John Hunter Thompson - whose vibrant portrait of Charlotte, sadly not shown in the production, suggests he may also have had a crush on her. Sylvestra Le Touzel and Cherie Lunghi have brief cameos as young girls taught by Anne and Charlotte respectively.

The use of the original locations is far beyond anything that might have been expected of the BBC at this point, even if some of the photography now seems dated. The costumes, props, and set decoration are wholly in period - it is refreshing that someone understood the stylistic differences between the earlier and later periods of the 19th Century - and add to the sense of total immersion in another time.

It would not be done better today.

Review: John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 2nd, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.