The Day After

1983 - United StatesHas a television show ever changed history? Did it perhaps even save the world?

The Day After reviewed by John Winterson Richards

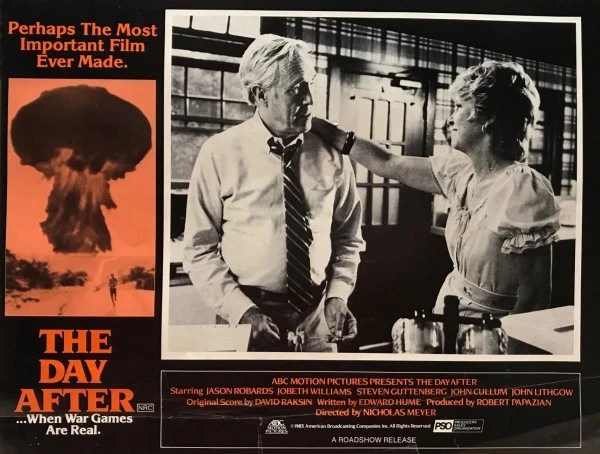

There is absolutely no doubt that The Day After, a television movie about the effects of a massive nuclear missile attack on the United States and its aftermath had a huge impact, if that is not a distasteful word in this context. It was one of the most watched shows in American television history, and the most watched television film, at the time. It ignited fierce debate, and the political and psychological effects reached right to the very top. After an advance screening at Camp David, the President at the time, Ronald Reagan, wrote in his private Diary, "It is powerfully done - all $7 mil. worth. It's very effective and left me greatly depressed. So far they haven't sold any of the 25 spot ads scheduled & I can see why. Whether it will be of any help to the 'anti-nukes' or not, I can't say. My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war. Back to W.H."

His first two sentences are actually a pretty good summary of the project - Reagan could have made a good living as a reviewer if politics had not worked out for him.

It should be noted that Reagan's Diary and his other private papers also make it clear that his fear of nuclear war was always fully the equal for his distaste for Communism, which is why he pursued a "twin track" strategy of re-armament and negotiation consistently throughout his political career. The notion sometimes suggested, or at least implied, that the film turned a hawk into a dove is therefore an exaggeration, but there is no denying its immense influence.

It was at the time extremely controversial because it was seen as a direct attack on the doctrine of nuclear deterrence. The plot is predicated on its failure, and there is a definite tinge of the usual Hollywood politics to the subtext of the script, which portrays the US Administration - fictional but apparently intended to be Reagan's - as imbecilic. Of course the doctrine of nuclear deterrence had worked perfectly up until that point, and has ever since, contributing to the surprisingly peaceful end of the Cold War. The film was nevertheless referenced frequently by the disarmament movement in the United States, which, while never as strong as it was at the time in Europe and the United Kingdom, was definitely strengthened as a result of its showing.

It was felt necessary to reassure the public with a high profile debate on nuclear strategy broadcast immediately after The Day After involving such heavyweights as Henry Kissinger and George Shultz. This was approved at the highest level, as Reagan notes in another entry in his Diary - "We know it's 'anti-nuke' propaganda but we're going to take it over & say it shows why we must keep on doing what we're doing." Soon after, in a move that seems unimaginable today, ABC, the network which made The Day After, responded to a complaint about one-sided politics by commissioning Amerika, a miniseries about the effects of a Soviet takeover of the United States, by way of balance - but it went on too long and had far less impact.

This is ironic because, reviewing The Day After forty years on purely as a drama, outside the immediate political context of its time, the one thought that occurs is that it might have been dramatically more effective as a miniseries, perhaps in three parts, one part to humanise the characters more and explain the political situation better, one to show the nuclear bombardment and its immediate effects in more detail (possibly in real time), and one to show the longer term effects.

As it is, we do not really get to know the characters properly or sympathise with them. We jump back and forth between several plotlines, all illustrating the effects of historical events on ordinary people, but none is very compelling. It all feels more like a set of subplots than a story.

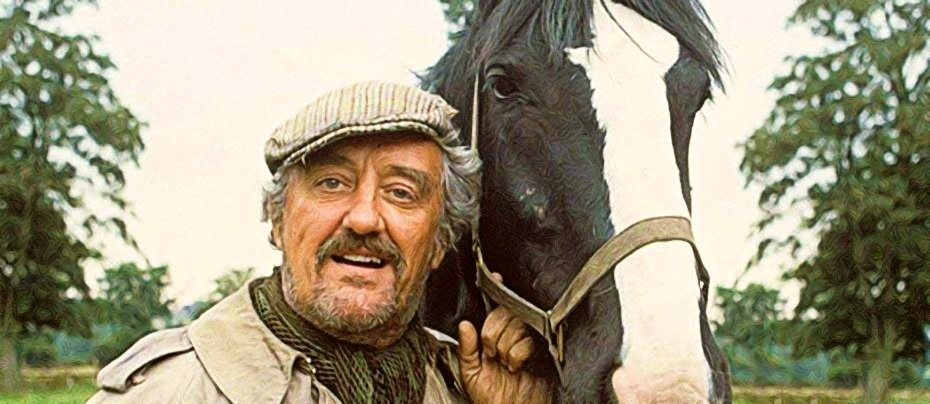

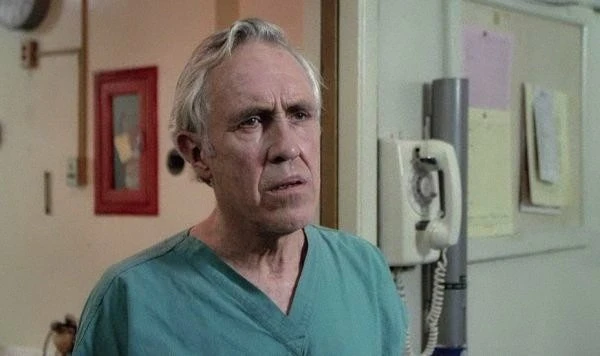

This is no negative reflection on a strong cast. Jason Robards is Jason Robards as a Jason Robards-like humane but weary surgeon. Georgann Johnson is his likeable wife in a neat cameo portrait of a credibly happy marriage, which is rare for television, and JoBeth Williams is his practical nurse. John Cullum (Northern Exposure) is authentic as a literally down to earth farmer, and Bibi Besch has a telling scene as his wife, who insists on making the beds before they rush down to their cellar, not comprehending how their lives as they know them are ending and such things no longer matter. Steve Guttenberg, little knowing he is about to become a comedy film star, is an amiable medical student who takes shelter with them. John Lithgow and Stephen Furst are among those who take refuge in a University Science Building who nevertheless have little idea what is going on. Apart from these more familiar faces, most of those appearing were locally recruited non-professionals intended to give a greater sense of authenticity.

That sense of authenticity is erratic in the final cut. By far the best parts are the documentary style scenes set aboard the command airplane, but these sit uneasily next to the soapier scenes of domestic drama before the missiles strike. Perhaps it might have been better to stick to the former style throughout. The abruptness of the strike itself is conveyed very effectively by director Nicholas Meyer, the eclectic, multitalented novelist and scriptwriter best known for directing Star Trek II: the Wrath of Khan, generally considered the best of the Star Trek feature films. It seems to invoke the Biblical prophecy of people eating and drinking and giving in marriage right up to the moment The End comes.

It has to be said that the special effects of the strike and its aftermath have not aged well. Showing those being vapourised briefly as X-rays seems positively corny, like something out of a bad Fifties science fiction B-movie. There is an overreliance on historical stock footage, some of it very familiar, to illustrate the blast. The recent streaming show Fallout actually did Armageddon better, despite being intended as a far more light hearted project.

The grey tinted aftermath in The Day After is also familiar from practically every other Post-Apocalyptic movie and show before or since. This is because it is substantially accurate, due the ubiquity of ash in such a situation, but it does invite comparisons and it has to be said it has been handled more convincingly elsewhere.

The strict standards imposed on network television at the time, combined with commercial considerations, limited what could be shown. Meyer seems to have been very conscious of that, apparently fighting a losing battle with the network in the name of greater realism throughout the production process, and, perhaps by way of necessary compromise, the film ends with a caption stating that the actual consequences would be worse. That is a huge understatement.

The British drama Threads, which was shown the following year, was in part a deliberate attempt to make up for The Day After pulling its punches a little. It adopts a far more realistic style to put it mildly. British television being what it is, Threads is also more overtly "political," which always means the same thing on both sides of the Atlantic. However, judging from what we have learnt since, for example from the break down of service systems in parts of the United States following Hurricane Katrina, the consequences of a total collapse of civilisation following such a full nuclear bombardment may be beyond the imagination of even the greatest pessimists of the Eighties. Just be grateful it never happened and careful it never does.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 30th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.