The New Statesman

1987 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

Modern satire is, if anything, rather tame. The 18th and early 19th Century cartoonists, like Gillray and Cruickshank, and the writings of Jonathan Swift, despite him being a clergyman noted for his private generosity, are positively vicious. Prompted by a definite partisan agenda, they pick out the most negative features of individuals on the other side, exaggerate them, and generalise them, so that the other side as a whole is held up to ridicule. It is a thoroughly dishonest process - but, done well, an effective political tactic and often very funny. Such is The New Statesman.

Writers Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran are openly men of the political Left. Although noted as prolific writers of middle grade situation comedies such as Birds of a Feather rather than as satirists, they like to sneak their politics into their regular work, so when a vehicle for Rik Mayall offered them the opportunity to go full political they rose to the occasion.

Alan Beresford B'Stard, MP, is a hyperbolic amalgam of everything Marks and Gran disliked in the Conservative Party, as they saw it, in the Thatcher Years. He somehow manages to combine the old school arrogance of an Alan Clark with the new money seediness of a Cecil Parkinson. He has the same middle name as Norman Tebbit. He is both an extreme libertarian and an extreme authoritarian at the same time, except he lacks the passion for social mobility that usually comes with libertarianism and the genuine paternalistic concern for the poor that softens most authoritarians. He is allowed no redeeming features. No Conservative MP like this has ever existed or could exist: there are too many contradictions. No matter. This is hard core satire as Swift would understand it.

B'Stard's political positions are as extreme as his personal characteristics. Needless to say, he adopts all the attitudes that are considered "right wing" - or were at the time - in their most exaggerated form. However, he goes beyond that: he says openly that he wants all the poor to die off, something not even the most radical libertarian MP has ever said, or, one hopes, thought. Again, no matter. This is full contact satire and the rules are that there are no rules.

B'Stard's ruthless ideology is a reflection of his own business practices, or perhaps vice versa. He wants to become wealthy by any means possible. He does not believe that business should be bound by ethics any more than he believes it should be bound by laws. There is a certain consistency in this, even if, in reality, political philosophies which assign a lesser role to regulation usually balance that by demanding greater responsibility.

In many ways the audience reactions to this deliberately absurd character were more interesting than the character himself. There is no doubt that B'Stard cast a long shadow. His influence endures to this day. Most viewers just had a good laugh, but those who take politics seriously took The New Statesman a bit too seriously.

Many on the Left decided to treat this extreme satire as established fact. It only confirmed what they had long believed - because they wanted believe it and perhaps needed to believe it - that there really were people like this in the Conservative Party and that they were indeed running it.

The reaction from the other side is curious. It is part of a more general reaction to the usual image of conservatives and libertarians of all stripes presented by the entertainment media, which is, it is fair to say, rarely complimentary. Some are at great pains to show how they are nothing at all like B'Stard. This was the thinking behind David Cameron's "hug a hoodie" campaign, trying to demonstrate a "kinder, gentler," more "compassionate conservatism."

Yet there are a minority who reject that approach and, according to the writers themselves, seem to play up to the image of B'Stard. Perhaps this is motivated by contrarianism, a determination not to be defensive or apologetic about not following the media driven herd, or perhaps it is based on the calculation that, in politics, it is better to have the high profile image of an extremist than no recognisable image at all.

It also has to be said that, grotesque as he is, there is something perversely attractive about B'Stard as played by Rik Mayall - a line which, by all accounts, would have pleased Mayall himself no end. B'Stard knows what he wants, and he is single minded, ingenious, and energetic in pursuit of it. Were it not for his total selfishness and amorality, he would have many of the attributes of a great leader. While he is not exactly a loveable rogue, because there is absolutely nothing loveable about him, he has a definite Flashmanesque anti-hero appeal, and there is something compelling about finding out what happens to him. Whether you want to see him to get his comeuppance or somehow to escape it yet again does not matter - what matters is that you have keep watching either way.

In the last regular episode of the show - spoiler alert - B'Stard becomes Lord Protector after winning a General Election on a populist promise to take Britain out of the European Economic Community, as it then was. This was doubtless chosen as a suitably unbelievable culmination of all B'Stard's unbelievable exploits because, back in 1992, everyone knew that nothing like that could ever, ever happen in real life...

Indeed, when the character returned in a stage show over a decade later, an alternative timeline was used in which B'Stard is revealed as the man responsible for "New Labour." That seemed a lot more credible at the time.

B'Stard's final appearance was, perhaps surprisingly, in a political advertisement for the "No" side in the Alternative Vote Referendum on 2011, in which he boasts that, with AV, he can promise absolutely anything in an election campaign, safe in the knowledge that a hung Parliament means he will never be called upon to deliver.

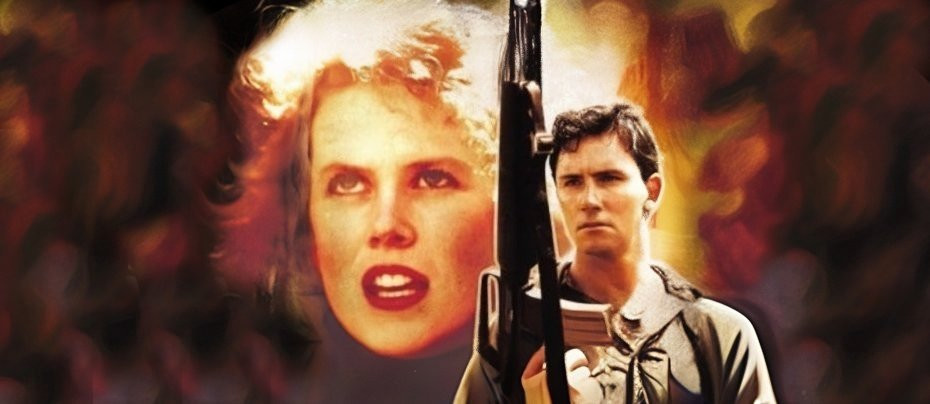

It is impossible to imagine anyone but Mayall as B'Stard. He was always at his best delivering over the top egotists, from Rick in The Young Ones to Lord Flashheart in the Blackadder saga, being fearless in taking comic risks and usually - not always - getting away with it. B'Stard is actually one of his more restrained performances and therefore arguably his best. It is certainly the role for which he is best remembered.

He was well supported. Marsha Fitzalan was fully his match as B'Stard's sneering and equally ruthless wife, Sarah. Michael Troughton was rather touching as his occasional right hand man, victim, stooge, and, by default, best friend, Piers Fletcher-Dervish, a potentially good man who becomes a cringing Renfield to B'Stard's exploitative Dracula.

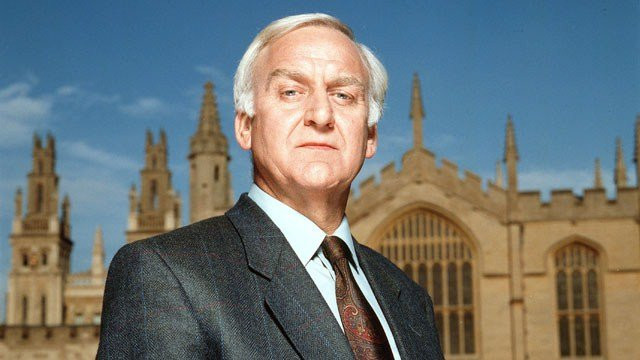

John Nettleton, best known as the manipulative Cabinet Secretary in Yes, Minister, was cast ironically as an old style Conservative MP out of his depth in a world in which B'Stards flourish. Terence Alexander was a more mature and smoother version of B'Stard, who found in the end that he was simply not ruthless enough to compete. Charles Gray turned up as Sarah's father, the Chairman of the Conservative Association in B'Stard's constituency, playing a part similar to the one he played in Porterhouse Blue around the same time.

The reliable John Woodvine was a Cromwellian Police Chief, clearly based on Sir James Anderton, the controversial Chief Constable of Greater Manchester at the time. Peter Sallis was a retired public executioner who kept a pub in B'Stard's seat and encouraged his MP to restore capital punishment so he could have his old job back. Benjamin Whitrow was a Left wing Labour MP used by Alan as a dupe. Brigitte Kahn - Dagmar in Auf Weidersehen, Pet, and apparently one of only four women to have lines in the original 'Star Wars' trilogy - was a German MEP when B'Stard did a stint in the European Parliament.

As satire, The New Statesman was never subtle. B'Stard's surname says it all. The actual funny bits were more often farcical than satirical. The viewer was clobbered over the head with a bludgeon rather than ticked with the rapier wit of a Yes, Minister. It was also biased. It never made a secret of that, which actually puts it ahead of equally prejudiced programmes that pretended to be neutral. In any case, most of the best satire is biased, and any party that is in power for any substantial period should expect to be satirised. It is healthy for democracy, one of those self correcting mechanisms that helps the whole system function. The Conservatives therefore have no right to complain - and, for the most part, did not: many seem to have enjoyed being satirised, or were at least bright enough to know that the best way to minimise any damage done by satire is to pretend to be a good sport and laugh along with everyone else.

Yet that does beg the question: why have we never seen the equivalent satire of the Labour Party in power? After all, the raw material is there. Robert Maxwell and John Stonehouse were closer to Alan B'Stard in their business dealings than any recent Conservative MP. Then there is the question of how Labour politicians, like Mr Blair and the late Lord Callaghan, enter public life with, by their own accounts, few business interests and end up very wealthy. Finally, there is the old standby of the Labour MP who makes a display of his simple working class tastes in his constituency but has an appetite for the finer things up in London - Aneurin Bevan was a well attested example. The Blair Years passed with all this potential comedy gold unmined.

What Mayall could have made of the last six years, sadly, we can only imagine...

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 16th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.