The Secret Service

1969 - United KingdomJust two days after Joe 90 finished filming, Gerry Anderson's next puppet series was in production. The Secret Service came about after a chance encounter between Anderson and comedian Stanley Unwin at Pinewood Studios during the making of Doppelgänger.

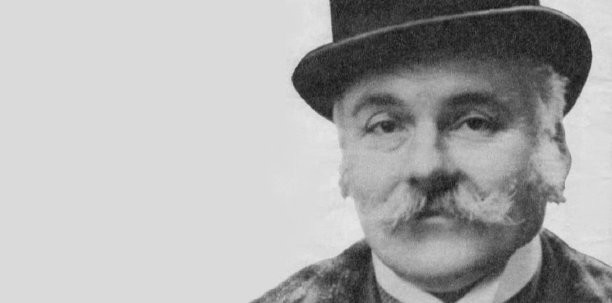

Unwin had found fame by twisting words into a nonsense language, which he called Unwinese, on radio and later TV. Born in Pretoria, South Africa, it was Unwin’s mother that unwittingly inspired him to develop this strange language when she fell over one day and told him she had "falolloped" and cut her "kneeclappers." Unwin further developed this by reading fairy tales to his children.

On radio, Unwin became something of an eccentric comic during the 1960's and often turned up in guest spots on television or played small parts in films, amongst his credits were Carry On Regardless, Press For Time and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. As a result, he gained a cult following, his ascension into this status came at the end of the decade when in 1968 he recorded the part of the narrator on The Small Faces' album Ogden's Nut Gone Flake. But Unwin’s humour worked best in short doses.

Initially, Anderson planned for The Secret Service to be a live-action series, but high production costs pushed him toward using a mix of live-action and puppetry. A puppet of Unwin was created, and production began in August 1968. The story followed Unwin as a country vicar who secretly worked as an agent for BISHOP (British Intelligence Service Headquarters, Operation Priest). However, it was an awful concept and made for an equally awful series. Compared to Anderson’s earlier shows like Fireball XL5, Stingray and Thunderbirds, which were packed with high-stakes action and excitement, The Secret Service felt slower and more subdued. The show didn’t have the same dynamic energy or thrilling sequences that audiences had come to expect from an Anderson production. The espionage plots often took a backseat to comedic moments, which weakened the tension and engagement of the episodes.

By the time Anderson presented the pilot to ITV’s Lew Grade, 13 episodes had been completed. However, when Unwin’s character began speaking in his signature Unwinese, Grade immediately halted the screening, declaring, “Cancel it! I don’t want any more made!” This outburst effectively ended The Secret Service and marked the close of Anderson’s era of Supermarionation puppetry.

Anderson may have been relieved at this outcome. By the time The Secret Service was produced, he had grown increasingly frustrated with the limitations of puppetry, despite having built his career around it with highly successful shows.

Anderson had always envisioned making live-action productions. Although he had found success in creating visually impressive puppet-based shows, by the late 1960s he felt creatively restricted by the medium. He was especially dissatisfied with the puppets' lack of expressive ability, particularly their immobile faces, which limited the range of emotion and storytelling possibilities, and although it is unlikely that he deliberately sabotaged The Secret Service, there's always the faint possibility that this was his intention.

By the time The Secret Service came along, it was clear that Anderson’s ambitions lay in live-action projects, which is another reason why the series incorporated live actors alongside puppets—an experiment in bridging the gap. Having wanted to abandon puppet work and move into live-action, Anderson greeted the cancellation of The Secret Service with optimism, saying of live actors: "I started to think, 'It's amazing! They speak! Their mouths are in sync with their words! And they can walk! And they can pick up things!'"

Anderson was never quite able to recreate the massive impact of Thunderbirds which remains his most iconic and beloved creation, and its combination of cutting-edge Supermarionation technology, thrilling action sequences, and engaging characters struck a chord with audiences both in the UK and internationally. The series became a cultural phenomenon and is still regarded as one of the most influential TV shows of its kind.

Contemporary critics were baffled by The Secret Service. Anderson had established a reputation for exciting shows, and this show felt like a stark departure. Critics couldn't understand the appeal of centring a children's TV show on a character like Father Unwin, who was neither dynamic nor relatable for a younger audience. Additionally, the inclusion of Unwinese—essentially gibberish dialogue—alienated viewers unfamiliar with Stanley Unwin's comedic persona. For many, the humour was simply too niche. It didn’t help that the plots, which often involved espionage in rural Britain, lacked the urgency or innovation typical of Anderson’s other work. Critics described the show as "odd" and "puzzling," often criticizing its slow pace and outlandish premise.

The blending of live-action with marionettes was intended to break new ground, but instead, it proved to be disorienting. The sudden switches between puppet and live-action characters came across as awkward and undermined any attempt at narrative immersion. This stylistic choice contributed to the show’s failure to capture the public's imagination. While Anderson had successfully employed marionettes in earlier shows, the reliance on puppetry here felt like a miscalculation, as it lacked the thrilling, futuristic settings that had previously made the technique charming. The Secret Service instead came across as stilted and old-fashioned, especially at a time when television was evolving rapidly.

ITV was also uncertain about placing the show. The Secret Service simply didn't fit into the programming of the era, which was leaning toward more dynamic and modern forms of entertainment. The combination of gentle comedy, old-fashioned values, and avant-garde technical choices proved too disjointed for mass appeal.

In hindsight, however, The Secret Service has been re-evaluated by some as a quirky cult classic. Modern critics and fans have come to appreciate its oddball charm, innovative production techniques, and Unwin’s unique comedic style, though it remains one of the more obscure entries in Gerry Anderson’s body of work.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 15th, 2024. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.