Two's Company

1975 - United KingdomReview – Brian Slade

The use of stereotypes in comedy has become a minefield in the modern world, but back in the 1970s they were commonplace in sitcoms. Among the less offensive was the idea that all Americans were brash New Yorkers and that all British were well-spoken upper-class people. This particular combination was exploited to comedy perfection in the hit sitcom Two’s Company.

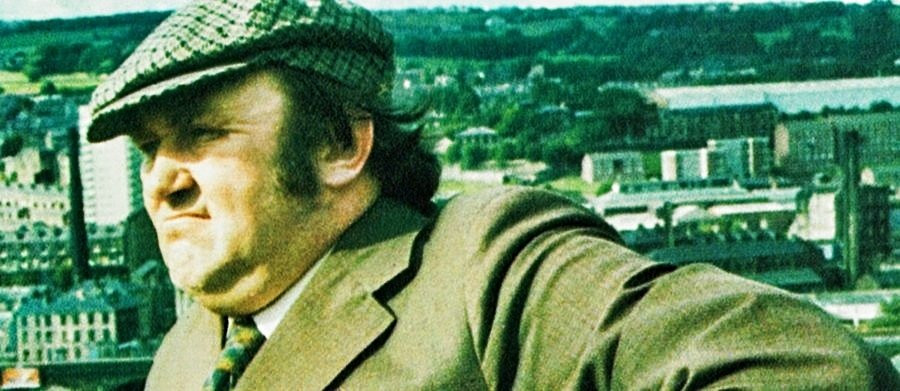

Two’s Company was the brainchild of Bill MacIlwraith and appeared on our screens in 1975. It told the story of an American thriller writer and her British butler, two hugely different characters from completely different cultures. As with any successful sitcom, alongside quality writing, casting was key and it’s safe to say that for Two’s Company, the casting was perfect. Elaine Stritch, a Broadway star who trained alongside Marlon Brando in New York, played the part of the sneering American who knows what she likes and doesn’t plan on being put down by a snooty butler. The butler himself was played by Donald Sinden, who, far from being a Broadway star, left school with little more than a severe case of asthma and qualifications only for a career in carpentry, but ended up becoming one of England’s most renowned theatrical greats.

The series got down to business within seconds, with the opening episode being exclusively a two-hander with the central characters. Dorothy McNab is a hugely successful thriller writer who has decided to escape her own country for the seemingly more genteel surroundings of 1970s central London. With publishers forcing her into producing 4,000 words per day, she decided she had a choice – get out or get a coronary.

In need of a butler, cook and handyman, McNab has entrusted the recruitment to an agency and their response is to send along Robert Hiller. Hiller has provided his services for many a satisfied client, but he is seemingly horrified to be sent to the employment of an American. It’s not something that bothers McNab, who retorts that, ‘I’m not madly in love with the British, so we might have something in common.’

For the most part of the first episode, the pair banter back and forth about McNab’s tastes compared with those that Hiller believes she should have. Her choices of wine, menu, how well done she likes her steaks… even cheeses are all dismissed by Hiller, who clearly believes his standards are far higher than his potential employer. After a series of bets and a convoluted wage and working conditions discussion, Hiller eventually accepts the position that now includes a 50% raise on his previous employer and a self-contained flat. It’s only after his hard bargaining that he reveals that he had planned to take the position all along.

Stritch is a glorious success and there is a glint in her eyes and a smile on her face that hints at genuine enjoyment at the battles with Sinden, such is the chemistry between the pair. Sinden himself is perfection. The dismissive nature of his superior dismissal of anything and everything his employer enjoys is carried out exquisitely, and it is little wonder that both stars received BAFTA nominations during the show’s run.

Much of the four series revolves around Hiller getting ideas above his station. Dismissing a multitude of tradesmen, events or visitors as inappropriate or sub-standard, he is largely at loggerheads with McNab in how things should look, taste or perform. But on occasion, the comedy switches to McNab’s attempts to deal with the quirks of life in Chelsea being so very different from the one she left back in Manhattan. For 29 episodes the show was quick-fire entertainment and went down a storm with its audience, such that it was nominated for a BAFTA for Best Comedy in its final year.

Stritch and Sinden were both primarily stage performers from opposite sides of the Atlantic, which is perhaps why the on-screen chemistry was so strong. They never missed a beat and for both of them there would be more on-screen success to come, Sinden with eleven years opposite Windsor Davies in Never the Twain, and Stritch taking a number of Emmy awards in the 1990s before a triumphant one-woman stage show.

Within his memoirs, Sinden remarked upon the perils and frustrations of recording in front of a live audience. Both he and Stritch wanted to record without a studio audience, saying they were torn between, ‘…playing to a non-representative 250 people in front of us and the hidden 15 million sitting in their homes.’ He once asked a group of ladies in the audience if, when watching the programme, they liked to hear a studio audience, to which they replied that they would because it gave them an idea of when to laugh. ‘What a tragic situation when we need others to tell us what is funny,’ he bemoaned. He needn’t have worried. Although rarely given repeat outings, Two’s Company didn’t need its studio audience to tell us when to laugh – it was pretty much from start to finish for four glorious years.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 14th, 2020. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.