University Challenge

1962 - United Kingdom“there is little time for conscious thought. It may come down to instinct”

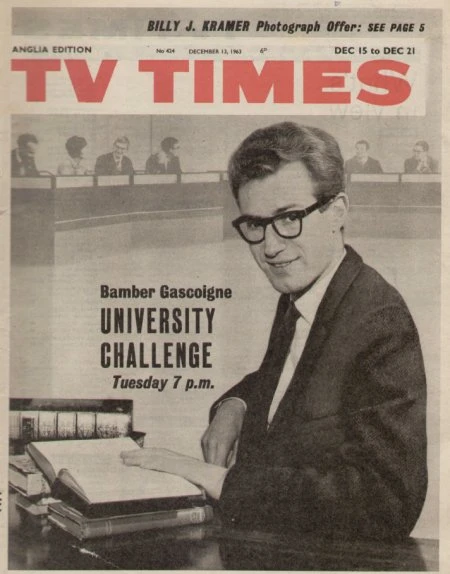

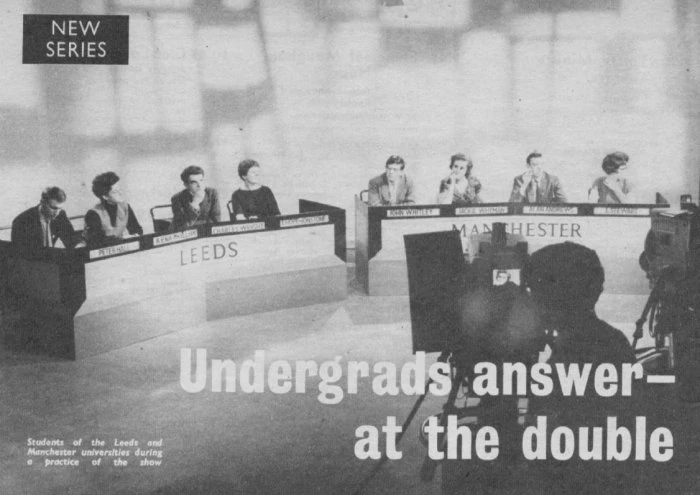

Prompted by the recent passing of Bamber Gascoigne, CBE, FRSL, and in honour of the show's 60th Anniversary this September, this is a personal review of the Granada University Challenge, the Gascoigne Years. For some of us, this is the only true University Challenge.

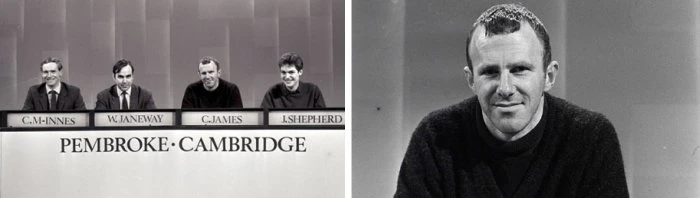

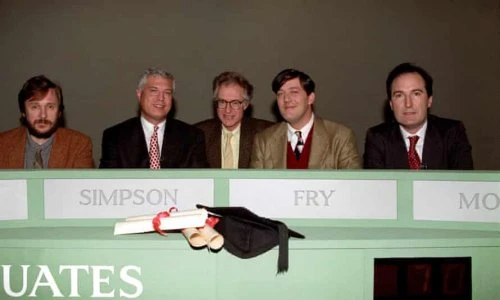

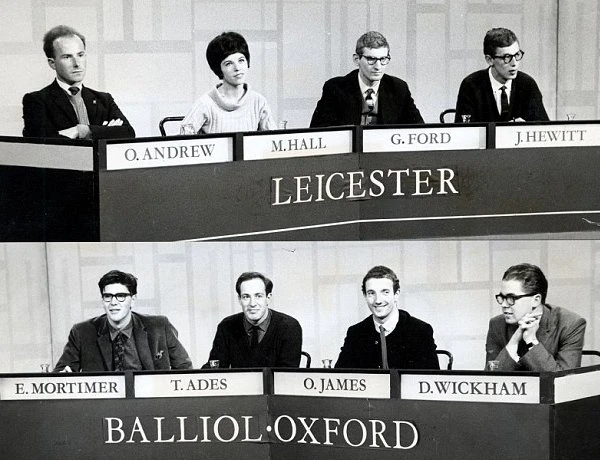

The basic format of the University Challenge is based on the American show College Bowl - in which participants included Hillary Rodham of Wellesley College, later to be known by her married name of Hillary Clinton. Participants in the British version include Malcolm Rifkind, Clive James, Julian Fellowes, John Simpson, David Mellor, Christopher Hitchens, and Stephen Fry.

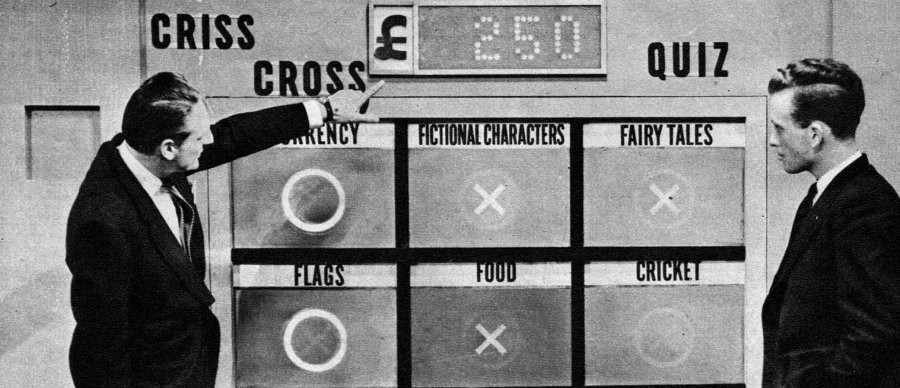

There are two teams of four, each representing a University or Oxbridge College. The quizmaster asks a "starter" question, and the first person to press a buzzer gets to answer it. Interrupting the question is permitted, but the quizmaster stops speaking as soon as the buzzer sounds, so it is a calculated risk. The question may not be what one assumes. If one gets the answer right, their team gets ten points, hence Gascoigne's famous catchphrase "Here's your starter for ten," and the exclusive opportunity for the team to answer a series of bonus questions, usually three, for a total of fifteen points in addition to the ten. If, however, one gets the "starter" question wrong, the other team gets the exclusive right to answer the "starter" question and all that goes with it.

One is allowed to confer with one's teammates when answering the bonus questions, with the team Captain making the final decision if there is debate, but, as Gascoigne kept reminding the contestants, no conferring was permitted on the "starter" questions. Contestants were made very much aware of the fact that they were completely on their own when their fingers were on the buzzers and the whole team depended on them not getting an answer wrong.

Answering the "starter" question is as much a test of speed of reaction and of nerve as of actual knowledge. Even as one is flicking through the filing cabinet of one's memory in search of what one hopes is the right answer, one is making several simultaneous calculations about timing. One obviously wants to hear as much of the question as possible, and one would prefer to take some time to think things through properly, so it would be better to wait as long as possible before buzzing - except the longer one delays, the greater the chances that someone on the other team, or a more impetuous member of one's own team, might buzz first. That is not necessarily a bad thing: the member of the other team might get it wrong, leaving one's own team the opportunity to answer at leisure, or one's own teammate may get it right. So one has to add a new level to one's calculations. In particular, one has to calculate if a teammate is more likely to come up with the correct answer, and in time, in which case it would better not to jump in. If, on the other hand, one thinks a teammate is more likely to get it wrong, it is necessary to forestall him. So one may be competing against one's teammates as well as the other team. Knowledge of one's own teammates, and of human nature, is therefore as important as knowledge of the facts.

The window for all these calculations may be less than a couple of seconds. There is little time for conscious thought. It may come down to instinct. The loneliness of a student waiting for a "starter" question is as intense as it is in a one on one quiz like Mastermind. Indeed, in one respect it is greater: make a mistake on Mastermind and you will only be annoyed with yourself; make a mistake on University Challenge and you will have let your whole team down.

One aspect of the quiz that was quickly dropped in the early days, was competitors faced the additional hazard that, at any stage throughout the game, they may be asked to speak for 45 seconds on any given subject. "Here -" producer Barrie Heads told the TV Times at the series launch, "the accent will be on wit rather than vast intimate knowledge of the subject."

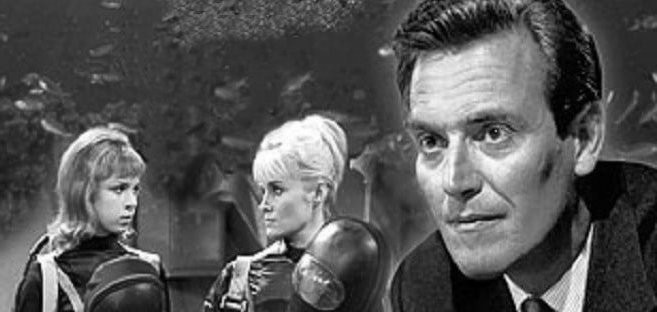

The questions on University Challenge were really not that difficult in the Gascoigne Years. At least it is easy enough to answer most of them watching comfortably at home. It is another matter altogether sweating in the studio with the lights blazing, the actual Bamber Gascoigne sitting right in front of you, a yelling mob of students to the side, and the knowledge that all your friends and family - and, it seems at that moment, everyone you will ever meet - is going to see this. At that point your mind is not on what Gascoigne is saying so much as on trying to ignore the growing feeling that you wish you had made at least one more trip to the toilet before leaving the dressing room. It is very easy to mishear a question in those circumstances or make a wrong assumption about where it is going.

No wonder that, on at least one occasion, Gascoigne was kind enough to point out that the team that was then trailing badly had actually won by the same margin in the rehearsal only a couple of hours before.

As if this was not enough, declining ratings towards the end of the Gascoigne years prompted the idea that the solution might be to bring some of the tension of one-on-one quizzes to University Challenge by introducing a fiendish rule change that is now generally forgotten. It often happens that a team coasts on the phenomenal general knowledge of one or two individual members. It is also good team selection to include people purely for their specialist knowledge. The rule change determined to negate that by testing the general knowledge of every single member of the team.

Each first round match was now divided into two episodes. The first was run according to the traditional format, but in the second a baton was passed along each team as in a relay race. One had to get two questions right to pass the baton to the next team member. Until then, one went head to head with the member of the opposing team who held their baton. Each team was therefore only as good as its weakest member.

Around the same time another rule change was intended to penalise premature buzzing on "starter" questions by deducting five points if the answer was wrong. One team got off to a spectacularly bad start by getting their first three "starter" questions wrong, so that they were at -15. The scoreboard had not been adapted to account for this possibility. At the fourth attempt they finally got the question right to win 10 points, prompting Gascoigne to remark "And if Bristol carry on at this rate, they might actually appear on the score board." Bristol went on to win that match.

There was yet another major alteration towards the end. Although a split screen effect always gave the impression one team was on top of the other, they were actually sat at the same level - until a new set was constructed so that, for a little while at least, illusion became reality and one team really was seated above the other.

At least one "starter" question was usually based on a picture, and another on a piece of music - but woe betide the contestant who assumed rashly that the question was simply to identify them! The bonus questions followed on naturally from the "starter," so that music was usually followed by more music and pictures by more pictures.

To be honest, there is nothing particularly clever or compelling about this format. The real reason for the success of University Challenge, and why the Gascoigne Years are still remembered so fondly, was Granada Television's choice of quizmaster.

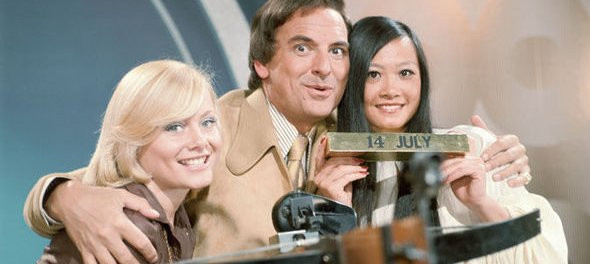

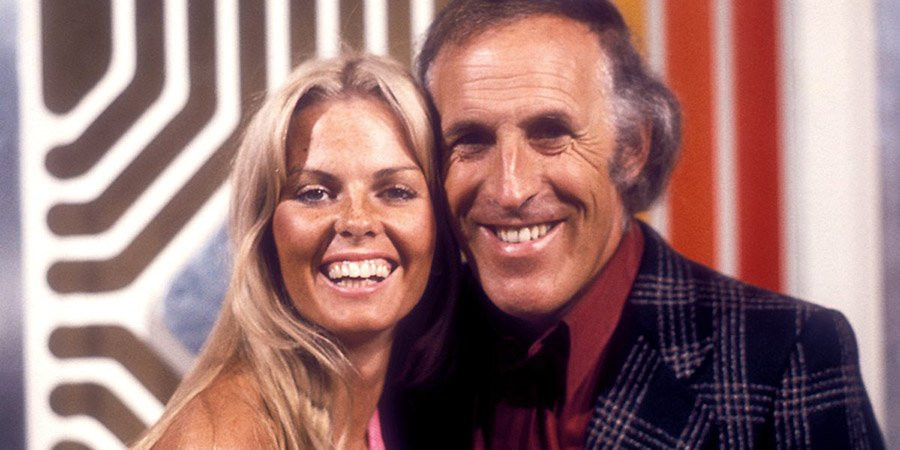

Bamber Gascoigne was exactly the sort of person who tended to get television jobs in 1962, and, for the same reason, would not get it today. An Old Etonian with two great grandfathers in the House of Lords, he had studied English under C S Lewis at Magdalene College, Cambridge, before going on to Yale as a Commonwealth Fund Scholar and National Service in, of course, the Grenadier Guards. He was working as a theatre critic and had written a musical of his own that had made it as far as the West End. It is surprising that someone with this background was not working for the BBC back then.

He turned out to be the perfect choice - and even became a minor sex symbol. He had an air of intellectual authority combined with charm that helped put nervous young people at ease. Although they were warned to avoid the temptation to steady their nerves with alcohol before filming, they wound down afterwards at an overly generous open bar where Gascoigne himself usually joined them There they were delighted to discover that he was in real life just what he appeared to be on screen - a extremely agreeable, well read, and intelligent gentleman in every sense of the word.

Unlike most television quizmasters, Gascoigne really did know the answers to the questions he asked. Contrary to some reports, he did not set them himself, but they were sent to his home a few hours before filming, so that he could check and research them in his private library. That way he could add to a partial reply and make an instant decision on an answer that might otherwise be open to debate.

His natural courtesy was sometimes tested by fractious young men - the overwhelming majority of contestants were male in those days. Most famously, a team from Manchester thought it would be hilarious to answer every question with the name of a Marxist leader. The joke wore very thin long before the end of the episode. Apparently, Gascoigne stopped the filming for a little while to explain, with his usual tact and consideration, that they were rather making fools of themselves. They did not listen and are at least remembered to this day - for making fools of themselves.

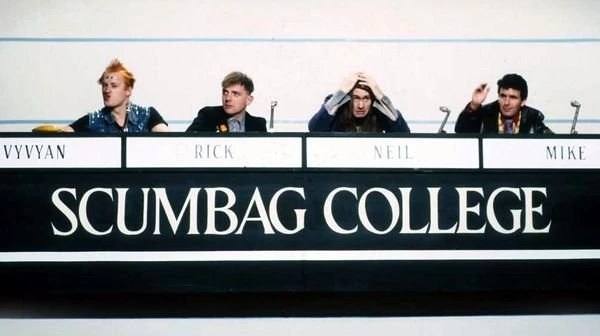

Gascoigne became something of a national treasure. He was played by Griff Rhys Jones in a famous Not the Nine O'clock News sketch, and again in 'Bambi,' probably the best remembered episode of The Young Ones as well as the highest rated on IMDb. He was also played by Mark Gatiss in the feature film Starter for Ten, the title of which refers to his famous catchphrase.

Everyone knew who he was, even people who never watched University Challenge. That was the problem: although it was part of the national fabric, the number of people who watched University Challenge was not that great and their numbers declined rapidly in the 1980s. In the usual vicious circle, they declined even more when relegated to less lucrative slots in the schedule.

Gimmicks like the new rules delayed cancellation but could not prevent it indefinitely. Granada is a business after all and ITV a commercial network. The show was eventually bought and revived by the BBC with Jeremy Paxman replacing Gascoigne as quizmaster, but it was never the same.

Gascoigne himself also wrote some well-regarded books and documentaries but for the most part seemed to disappear from television after he lost University Challenge. Perhaps he really did have better things to do, serving as a Trustee of both the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery, a Director of the Royal Opera House, and a Member of the Council of the National Trust. Late in life he inherited West Horsley Place, a charming stately home, from his aunt, the Duchess of Roxburghe. He succeeded in preserving it before handing it over to the West Horsley Place Trust. Television buffs will recognise it as "Button House" in the BBC comedy Ghosts.

He seems to have lived a very full and useful life, but it is for University Challenge that he will be remembered with real affection, above all by the young people who took part in it.

Review: John Winterson Richards (Captain of the Bristol University Challenge team in 1985) 9 February 2022

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 10th, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.