Doctor Who: Genesis

“It had to be a children's programme and still attract both teenagers and adults.”

2023 will be celebrated by Doctor Who fans as the 60th anniversary of the world’s longest running science fiction series. And quite rightly so. However, it was with radical restructuring plans born out of necessity, made by the BBC in 1962 that the seeds were sown for what was destined to be the most iconic show in the history of British television.

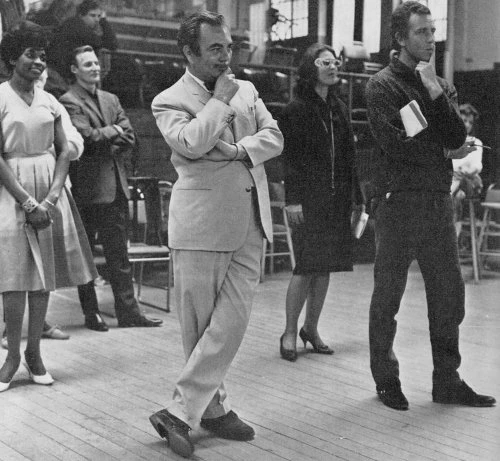

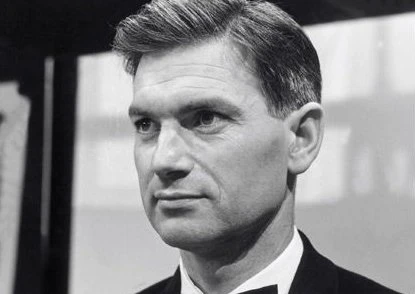

The first tentative steps towards the restructuring of BBC programming were made the year before, in 1961. With the BBC suffering from the success of Britain’s first independent stations, Sir Hugh Greene, the Corporation’s Director General, asked three of his top executives to sound out Canadian born producer Sydney Newman for the post of Head of Drama. Newman had already had great success with ABC Television as producer of its hugely popular drama series Armchair Theatre and the science fiction anthology series Out Of This World. As a result of this request, and around Christmas of that year, a series of discreet meetings took place in a Marylebone pub and, successively, Kenneth Adam (Director of Television), Donald Baverstock (Assistant Controller of Programmes) and Stuart Hood (Controller of Programmes, Television) had met with Newman to discuss the post.

Newman remembered it slightly differently years later and said the initial approach to him (by Kenneth Adam) was to produce the BBC’s Sunday night plays. Newman turned Adam down flat. He was already producing Sunday night dramas for a company that he was perfectly happy working for. It was only after his refusal to leave ABC that he was offered Head of Drama. “I took the job” he said, “because it gave me scope in areas of drama that had never been allowed me before.”

Newman would go to the BBC as soon as ABC would let him go, or if the worst came to the worst, in April 1963 when his ABC contract ran out. Until then the BBC drama department would continue under the headship of Norman Rutherford. Unsurprisingly, ABC were reluctant to let Newman go.

During his ABC tenure Newman had almost single-handedly shaken up the staid and predictable format being presented to viewers which, in his opinion, paid lip-service to the obvious class differences that he'd come across in Britain.

"At the time, I found this country to be somewhat class-ridden." Newman later recalled. "The only legitimate theatre was of the 'anyone for tennis' variety, which, on the whole, presented a condescending view of working-class people. Television dramas were usually adaptations of stage plays, and invariably about upper classes. I said, 'Damn the upper-classes-they don't even own televisions!' My approach was to cater for the people who were buying low-cost things like soap every day. The ordinary blokes the advertisers were aiming at." Having revolutionised the independent television service, Newman, who was finally allowed to leave ABC in December 1962, now set his sights on the BBC.

Newman decided that the first thing he needed to do at the BBC was to break up the existing structure of the Drama Department and reform it into the Drama Group. This new section was to cover three new departments: Series, Serials and Plays. For many years a Producer was expected to produce, direct, and liaise with the writer on his script. Under a shakeup of this system each Producer was to be allocated a Director and Story Editor, leaving him (invariably a ‘him’ because in those days television was very much a male-dominated domain) free to oversee the production in a far more strategic manner. “Many directors were stylistically old fashioned.” Newman later recalled. “Some had actually directed television in the pre-war days!” Newman created three new departments, one for single plays, one for series and one for serials. “The next thing I did was completely eliminate the Script Department.” Each of Newman’s three new sections had a Department Head, a small number of administrative staff, a secretary, a business manager – under who worked seven or eight producers each with a story editor - and two or three directors. By 1963, with the restructuring in place, Newman was free to develop new programmes for the BBC to challenge what was rapidly becoming ITV's supremacy.

By the time Newman had arrived at the BBC there had been a drop in ratings on Saturday afternoon between the highly popular sports programme Grandstand and the equally popular pop music programme Juke Box Jury. Newman was asked if he could come up with a children’s drama which would sustain the ratings and start building towards Saturday evening. "I vaguely recall a children's classic drama series that filled the slot." Said Newman. "Charles Dickens dramatizations, that sort of thing. I decided that this could be moved to Sunday afternoons if the Drama Department could come up with something more suitable. So we required a new programme that would bridge the state of mind of sports fans and the teenage pop music audience, while attracting and holding the children's audience accustomed to their Saturday afternoon serial."

Newman described his basic outline for the new show; "It had to be a children's programme and still attract both teenagers and adults. Also, as a children's programme, I was intent upon it containing basic factual information that could be described as educational, or, at least, mind opening for them. So my first thought was of a time-space machine with contemporary characters who would be able to travel forward and backward in time, and inward and outward in space. All the stories were to be based on scientific or historical facts as we knew them at the time." According to Newman he passed a memo on to Donald Wilson, whom he'd appointed as Head of Serials, and told him “Here’s a great idea for Saturday afternoons."

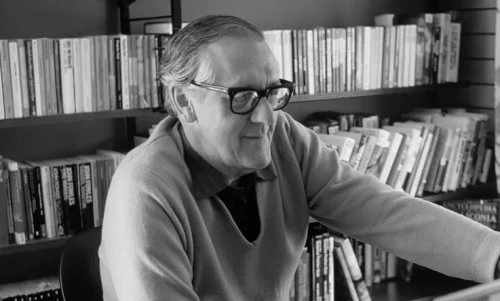

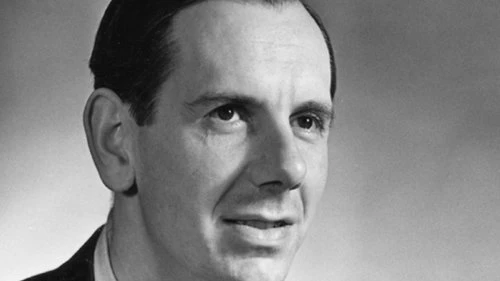

Donald Wilson, who had joined the BBC in 1955, had by 1960 established the Monitoring Group (later to be called the Survey Group), the objective of which was to study and report on other media such as radio, films, stage and books (and more importantly, the enemy: Commercial Television) in order to keep up to date with current trends and in particular to identify any new talent that could be used by the Corporation. In March 1962 (before Sydney Newman joined the Corporation) Eric Maschwitz, the Head of Light Entertainment asked Wilson to report on the literary genre of science fiction to evaluate its potential for a series of single dramas.

In hindsight, this appears to be an odd sort of request as the BBC had previously had a great deal of success in the sci-fi genre with three series of Quatermass over a five-year period. Arguably the most successful was Quatermass and the Pit – produced between 1958 and 1959 – as well as A for Andromeda (1961) – and its sequel, The Andromeda Breakthrough would soon go into production. Science fiction was clearly not unfamiliar ground for the Corporation. Perhaps the BBC were looking over their shoulder at ITV’s run of successful science fiction dramas (Target Luna and the Pathfinders series) aimed at a family audience and were considering how they could reproduce their appeal. Wilson assigned Donald Bull and Alice Frick of the Monitoring Group to complete a report to determine the viability of science fiction for future presentation.

Bull and Frick quickly presented Wilson with a scant three-and-a-half-page report. The opening line of the report states: “In the time allotted, we have not been able to make more than a sample dip,” suggesting that the report was requested as something of a rushed study. To assist, Bull and Frick utilised previous studies made by prolific authors Brian Aldiss, Kingsley Amis and Edmund Krispin. They claimed that this afforded them the opportunity to give a fair view of the subject, although it is unclear when these previous studies had been undertaken or if they were still relevant. Alice Frick did, however, speak personally to Aldiss, who at that time was the editor of Penguin Science Fiction and Honorary Secretary of the British Science Fiction Association. Aldiss offered to make suggestions for further reading but it is unknown if this offer was taken up by Bull and Frick. What is known is that their submitted report rather superciliously noted that “SF is overwhelmingly American in bulk” and “largely a short story medium.” The more sophisticated type of story, it claimed, relied on the “Threat to Mankind, and Cosmic Disaster” narrative, which was more favoured by British authors and the most suitable for TV adaptation (as opposed, one would presume, to ‘little green men’ or ‘bug eyed monsters’). They did, however, have reservations about using British writers of the genre stating that their choice would be “exceptionally narrow, boiling down to a handful of British writers.”

The report, which at times comes across as full of contradictions, added that: "It is interesting to note that with Andromeda, and even with Quatermass, more people watched them than liked them. People aren't all that mad about SF, but it is compulsive, when properly presented." It appears to support TV science fiction calling it a “most fruitful and exciting area of exploitation” but is cautionary in its assessment that the genre has thus far “not shown itself capable of supporting a large population.” As a perfect example of sitting on the fence, the report concluded that it is “not an automatic winner” and suggested that perhaps future audiences “will get a taste for it.” It also advised that if taken up, TV dramatists rather than science fiction writers should write it. “There is a wide gulf between SF as it exists, and the present tastes and needs of the TV audience, and this can only be bridged by writers deeply immersed in the TV discipline.” Despite a number of reservations, the report read in its entirety did find the genre interesting and intelligent and this was enough for Donald Wilson, in spite of the fact that Bull and Frick had written in their report “we cannot recommend any existing SF stories for TV adaptations”, to ask Frick and her Script Department colleague John Braybon, to do just that.

In a document submitted on Wednesday 25 July 1962, Frick and Braybon reported back that having read “hundreds” of science fiction stories “over the last eight weeks” they had chosen some potentially suitable stories because - “They do not include Bug Eyed Monsters; The central characters are never Tin Robots; They do not require elaborate settings,” and “they provide for genuine characterisation. We consider that two types of plot are reasonably outstanding, namely those dealing with telepaths and those dealing with time travelling.”

Based on this report, the BBC - already familiar with the audience pleasing potential of science-fiction, also exampled by their stunning adaptation of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty Four - moved ahead with the active development of potential new genre projects. This culminated in a four-part serial called The Monsters (which debuted at 8pm on 8 November 1962) written by Drama Script supervisor Vincent Tilsley in collaboration with playwright Evelyn Frazer, and directed by Mervyn Pinfield.

Sydney Newman arrived at the BBC on 12 December 1962. In early March 1963 he met with Donald Baverstock (Chief of Programmes) and Joanna Spicer (Assistant Controller (Planning)) to discuss potential programmes to fill the early Saturday evening slot. As a result of this meeting Baverstock asked Donald Wilson to come up with a suitable format for a 52-week science fiction series comprised of shorter serials. On 26 March 1963, a meeting was called by Donald Wilson which was attended by Frick, Braybon and Script Department writer C.E. (Cecil Edwin) Webber (known within the BBC by the affectionate nickname 'Bunny'), an experienced staff member who had been responsible for many successful children's drama. The aim of the meeting was to discuss ideas for the possible new series using the Monitoring/Survey Group’s 1962 report on science fiction.

On Wednesday 29 March, Alice Frick sent a memo to Wilson detailing the main story suggestions, which arose from the meeting. Briefly, these included the following core concepts:

1. Time Machine: Which Wilson suggested should be used for not only travelling backwards and forwards in time, but also into space and all kinds of other matter. (e.g. a drop of oil, a molecule, under the ocean, etc.)

2. Flying Saucer: Frick favoured this especially amongst other things, on the grounds that it might be seen as a more modern device and held the advantage of conveying a regular cast of characters.

3. Computer: This suggestion was quickly dropped when Wilson pointed out that it was basically the same central story device used in the Andromeda serials.

4. Telepathy: All concerned agreed that this was an "okay notion" in (then) modern science, and a good device for dealing with extra-terrestrials who have appropriated human bodies.

5. John Braybon put forward the idea that the series should actually be set in the future and involve what he considered a good dramatic device – a world body of scientific trouble-shooters, established to maintain control of scientific experiments for political or humanistic reasons. This particular idea of Braybon's is an excellent illustration of how a basically sound dramatic theme will eventually find an outlet. Over a decade later Gerry Davis and Dr. Kit Pedler developed a variation of Braybon's suggestion into the highly regarded BBC science-fiction thriller series, Doomwatch.

As to regular characters for the embryonic series, Wilson felt that what was needed was a core group from which individual characters could be rotated in so certain ones would feature in central roles in certain stories while taking a background role in others. He further suggested, given the timeslot earmarked for the series, that two of the characters should be teenagers However, Frick, Braybon and Webber argued against the idea on the grounds that children are usually more inclined to be interested in older characters, often in their early twenties that they can aspire to, than in those of their own age group.

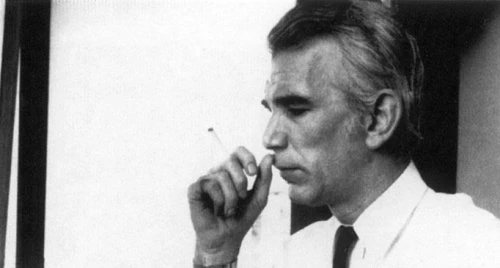

They all agreed the one major difficulty which needed to be overcome was how to involve all the characters from the core group while transporting them to different locations and in such a way as to make it as believable as possible, albeit within a science fiction framework. At this point that particular problem was not resolved. The meeting ended with Wilson asking Webber to submit a document outlining a set of viable characters. Webber did just that and eventually delivered his document to Wilson under the heading 'Science Fiction.' It stated that the series he envisaged would be a "loyalty programme", lasting at least 52 weeks, consisting of various dramatized science fiction stories which would be linked to form a continuous serial, using basically a few characters who continue through all the stories.

The report suggested:

“Our basic set-up with its loyalty characters must fulfil two conditions:

1. It must attract and hold an audience.

2. It must be adaptable to any SF story, so that we do not have to reject stories because they fail to fit into our set-up."

Webber also made suggestions for a group of characters that would appeal to a cross section of the child and teenage viewing audience:

THE HANDSOME YOUNG MAN HERO: (First character)

A character who would automatically engage the interest of the child/teenage audience of both sexes. What was needed to involve the older female section was the provision of:

THE HANDSOME WELL-DRESSED HEROINE AGED ABOUT 30: (Second character)

Webber then turned his attention to the adult male audience with the following comments: "Men are believed to form an important part of the five o'clock Saturday (post-Grandstand) audience. They will be interested in the young hero; and to catch them firmly we should add:"

THE MATURER MAN, 35-40, WITH SOME 'CHARACTER' TWIST: (Third character)

Webber summated several key points as being of importance to the developing series success: "Nowadays, to satisfy grown women, father-figures are introduced into loyalty programmes at such a rate that TV begins to look like an Old People's Home: let us introduce them ad hoc, as our stories call for them.

Interestingly, there was no suggestion for a fourth regular character but a suggestion that “we shall have no child protagonists, but child characters may be introduced ad hoc, because a story requires it, not to interest children.”

Webber then created the fictional backdrop for the characters. His main suggestion for this was that the regular characters should be the partners in a firm of scientific consultants known as:

'THE TROUBLESHOOTERS'

Webber's conception expanded upon John Braybon's original idea of a group of scientists where each character was a specialist in a certain field. He also suggested that a key component of the character dynamics was that if the two male characters sometimes became too pure in their scientific thinking, the woman would be on hand to always remind them that, ultimately, they are dealing with human beings.

Following a brief outline of the team's base of operations, and the suggestion that villains should be created on an ad hoc basis unless a recurring adversary emerged during the development of the stories, Webber's document concluded with a section headed 'Overall Meaning of the Serial', which stressed that television science fiction should be more character based than in literature and that it should have some "...feminine interest" and added that it should also "consider, or at least firmly raise" serious philosophical and moral questions. Following Wilson's reading of both Frick's report and Webber's document, they were forwarded to Sydney Newman for comment.

During early April 1963, after considering Frick and Webber's notes, Newman made a number of hand-written annotations to key sections of the document. These included his dislike of Alice Frick's Flying Saucer suggestion on the grounds that it was: "Not based in reality-" and "too Sunday press." The team of scientific trouble-shooters idea was dismissed with a definite: "No." Determined that the series should have some educational value he noted that within the submitted outline of the team of scientists there was: "…no one here to require being taught", and to allow for this he further noted under the character suggestions that there needed to be ‘a kid’ to get into trouble and make mistakes.

His overall opinion on the ideas and suggestions contained in the documents was that they were too highbrowed and unimaginative, and in the limited mould of traditional family drama from which he very much wanted to make a break. Newman's own format ideas favoured the approach of his own Pathfinders productions for ABC, which continued the old cinema tradition of using cliff-hangers as an integral part of children's adventure fare. Newman did approve one suggestion: the idea of a time-space machine.

While giving approval to Webber's suggestion for the 'Handsome Young Man Hero' and 'Handsome Well-dressed Heroine', Newman insisted that not only must a young teenager be added as an integral part of the character set, but also in place of Webber's 'Mature Man', he devise the character of a frail and grumpy old man. A man who had stolen the time machine from his own unnamed people, who belong to an advanced civilisation on some far distant alien planet. The time machine would, he said “be driven by an old man of 760 years of age who had fled from outer space where his planet had been taken over by some horrible enemies. I wanted a crochety, old guy who really is acutely intelligent and intrinsically kind, but as an old, senile man, he’s more impatient with his own incompetence which he takes out on others around him and that’s what makes him interesting to watch.”

The name given to the character by Sydney Newman was as ambiguous and mysterious as his character's true origins. The name was simply, "The Doctor", and with it he became the focal point of the entire series.

Around this time, Newman appointed Donald Wilson to the post of Head of the new Serials Department, which would actually be responsible for the production of the new serial.

In early May 1963, veteran producer/director Rex Tucker attended a meeting with Sydney Newman and Richard Martin, a young director who had recently been assigned to the Serials Department. Newman asked Tucker to take charge of the proposed new science fiction series pending the appointment of a permanent producer under Newman's newly instigated production team system.

Later discussions ultimately led to the series acquiring the title Doctor Who. At a later date, a friend of Tucker's, actor/director Hugh David, would make the claim that it was Tucker himself who originated the title. However, Tucker himself always maintained that the credit for the title belonged wholly to Sydney Newman. “I remember coming home and talking to my wife, Jean, about this new project and telling her I did not particularly want to work on it, but as I was due to go on holiday, I decided to help out with the casting sessions.” Tucker told Doctor Who Magazine in 1995.

Meanwhile, Newman's wide-reaching changes at the BBC continued inexorably towards their final realisation, with the final remnants of the old Script Department becoming the Television Script Unit. Bunny Webber, in the meantime, had drafted a document what was essentially intended to be a prospective 'series bible', under the heading ‘General Notes on Background and Approach.’ It opened by laying down the basic format for the series: "A series of stories linked to form a continuing serial. Within the overall title, each episode is to have its own title." He then went on to briefly sketch the basic standard template for the overall episode structure which was destined to endure virtually unchanged for decades: "Each episode of 25 minutes will begin by repeating the closing sequence or final climax of the preceding episode; about halfway through, each episode will reach a climax, followed by blackout before the second half commences (one break)."

Webber then went on to offer prospective writers’ advice on production requirements: "Each story, as far as possible, is to use repeatable sets. It is expected that B.P. (Back Projection) will be available with a reasonable amount of film, which will probably be mostly studio shot for special effects. Certainly, writers should not hesitate to call for any special effects to achieve the element of surprise essential in these stories, even though they are not sure how it should be done technically: leave it to the effects people." He concluded on a cautionary note, which would become almost a constant watchword for the future: "Otherwise work on a very modest budget."

As for the four central characters, Webber briefly outlined them with the following descriptions:

BRIDGET (BIDDY)

A with-it girl of 15, reaching the end of her Secondary School career, eager for life, lower-than-middle class. Avoid dialect, use neutral accent laced with latest teenage slang.

MISS MCGOVERN (LOLA)

24. Mistress at Biddy's school. Timid but capable of sudden rabbit courage. Modest, with plenty of normal desires. Although she tends to be the one who gets into trouble, she is not to be guyed: she is also a loyalty character.

CLIFF

27 OR 28. Master at the same school. Might be classed as ancient by teenagers except that he is physically perfect, strong, and courageous, a gorgeous dish. Oddly, when brains are required, he can even be brainy, in a different sort of way.

These are the characters we know and sympathise with, the ordinary people to whom extraordinary things happen. The fourth basic character remains always something of a mystery and is seen by us rather through the eyes of the other three....

DR. WHO

A frail old man lost in space and time. They give him this name because they don't know who he is. He seems not to remember where he has come from; he is suspicious and capable of sudden malignance; he seems to have some undefined enemy; he is searching for something as well as fleeing from something. He has a "machine" which enables them to travel together through time, through space, and through matter.

Webber's 'bible' then included the ‘essential components’ of the series, including such considerations as quality of story where Webber impressed upon prospective writers the somewhat odd notion that: "...we are not writing science fiction. We shall provide scientific explanations sometimes, but we shall not bend over backwards to do so if we decide to achieve credibility by other means. Neither are we writing fantasy: the events have got to be credible to the three ordinary people who are our main characters. They (the audience) are sharp-witted enough to spot a phoney."

Webber's next observation was no doubt influenced by his own experience in the children's drama field: "I think the writer's safeguard here will be, if he remembers that he is writing for an audience aged fourteen...the most difficult, critical, even sophisticated, audience there is, for TV. In brief, avoid the limitations of any label and use the best in any style or category, as it suits us, so long as it works in our medium."

Webber then turned his attention to the series main mode of transport with the following: "When we consider what this look like, we are in danger of either science-fiction or fairy-tale labelling. If it is a transparent plastic bubble we are with all the low-grade space-fiction of cartoon strip and soap-opera. If we scotch this by positing something humdrum, say, passing through some common object in the street such as a night-watchman's shelter to arrive inside a marvellous contrivance of quivering electronics, then we simply have a version of the dear old Magic Door. Therefore, we do not see the device at all; or rather it is visible only as an absence of visibility, a shape of nothingness (inlaid, into the surrounding picture)...

“The machine is unreliable, being faulty. A recurrent problem is to find spares. How to get thin gauge platinum wire in B.C.1566? Moreover, Dr. Who has lost his memory, so they have to learn to use it, by a process of trial and error, keeping records of knobs pressed and results (this is the fuel for many a long story). After several near-calamities they institute a safeguard: one of their number is left in the machine when the others go outside, so that at the end of an agreed time, they can be fetched back into their own era. This provides a suspense element in any given danger: can they survive till the moment of recall? Attack on recaller etc.”

Whilst Sydney Newman commented in handwritten notes "Good stuff here", he didn’t like the suggestion for the depiction of the Time Machine on the grounds that it was "not visual," and his feeling was that when it came to the machine a "tangible symbol" was needed. His reaction noted at the close of the opening paragraph was that each episode must end on a "very strong cliff-hanger".

Webber had also written a section called ‘THE SECOND SECRET OF DR. WHO.’ “The authorities of his own (or some other future) time are not concerned merely with the theft of an obsolete machine; they are seriously concerned to prevent his monkeying with time, because his secret intention, when he finds his ideal past, is to destroy or nullify the future.” Sydney Newman’s reaction to this was the handwritten word “Nuts”. He noted: "I don't like this much. It doesn't get across the basis of teaching of educational experience - drama based upon and stemming from factual material and scientific phenomena and actual social history of past and future. "

Possibly as a result of Newman’s concern with the development of the concept, on Monday 13 May, Ayton Whitaker circulated a memo to all concerned advising them of the postponement of the new Saturday serial by four weeks. Two days later, following further discussions with his colleagues on the project, Bunny Webber had completed a revised draft of his format document.

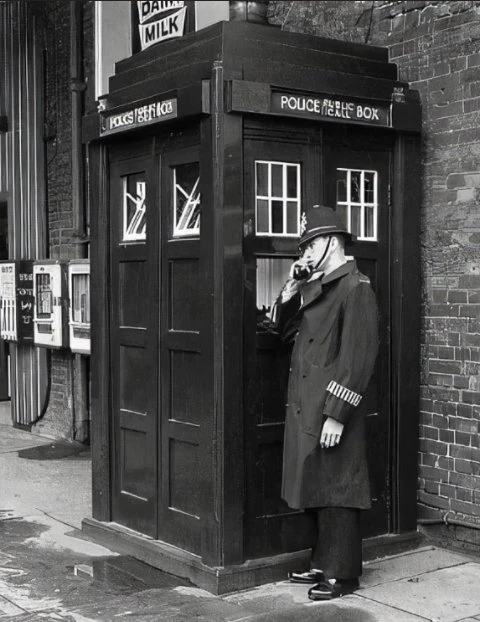

The latest draft's revisions took all of Newman's suggestions into account. This meant that all material produced under the heading 'Overall Continuity of Story', including the section which Newman had particularly disliked, 'The Secrets of Dr. Who', were removed. The name 'Biddy' for the young girl character was dismissed, with Webber now suggesting one from a list of alternatives - Mandy, Gay, Sue, Jill, Janet and Jane. However, the most important alterations came under the heading of 'THE MACHINE' which had been amended thus: "Dr. Who has a 'machine' which enables them to travel together through space, through time and through matter. When first seen, this machine has the appearance of a police box standing in the street, but anyone entering it is immediately inside an extensive electronic contrivance. Though it looks impressive, it is an old beat-up model which Dr. Who stole when he escaped from his own galaxy in the year 5733; it is uncertain in performance and often needs repairing; moreover, Dr. Who has forgotten how to work it, so they have to learn by trial and error."

The new concept for the time machine’s novel external appearance had been suggested by another BBC staff writer who Donald Wilson had recently allocated to the new series by the name of Anthony Coburn. Coburn's inspiration for the craft’s eccentric outer shell had flourished when he had seen a police box while out walking near his office. Coburn's simple, yet unusual suggestion, had given final form to what would become an instantly recognisable visual icon for the series.

Years later, Newman claimed that this ‘recognisable visual icon’ had always been at the heart of his original vision for the time machine. “I thought of a time/space machine, and the cute thing about it was the fact that it was to be a very common place object. It could have been an old car or anything. I’ve never claimed that the police box was my idea, only that it be a kind of space machine that would be small and common place on the outside and that it would be enormous on the inside.”

The last draft of the document also included the proposed outline of the first story:

"Mandy/Sue meets the old man wandering in the fog. He takes her to a police box in the street. Entering the box, she finds herself inside this large machine; directly she leaves it she is again in the street outside the police box. Cliff and Lola, who have been to a late meeting at the school, come cross Mandy/Sue and the old man: She shows them the machine. They are reduced in size, to about one-eighth of an inch tall, and the story develops this situation for four episodes within the school science laboratory. The next story will begin with their regaining normal size, and at once start them on another adventure."

Donald Wilson made a number of hand-written annotations to Webber's latest effort. Apart from some minor changes of wording, Wilson's most important revisions consisted of putting a cross through the Doctor's character description, indicating that he felt this needed extensive revision, he confirmed the name for the young girl character as Sue, and changed the paragraph heading for the time machine from 'The Machine' to 'The Ship'. Webber produced another draft (on 16 May) of the format document which Wilson again made hand-written annotations to, resulting in a further draft being typed up which accommodated further changes.

Monday 20 May found Sydney Newman now satisfied with the much-revised format document. His next step was to forward a copy of it to Donald Baverstock, along with the following memo: "This formalises on paper our intentions with respect to the new Saturday afternoon serial which is to hit air on 24 August. As you will see, this is more or less along the lines of the discussion between you and Joanna Spicer some months ago. Those of us who worked on this brief, and the writers we have discussed assignments with, are very enthusiastic about it. If things go reasonably well and the right facilities can be made to work, we will have an outstanding winner on our hands."

The next day, Ayton Whitaker sent a memo stating that due to the previously notified four-week postponement of the recording of the first episode, the anticipated pre-filming at the BBC's Television Film Studios in Ealing should also be put back by a further four weeks, which would result in filming for the first story to take place in the week commencing Saturday, 20 July. Later that same day, Whitaker sent a follow-up memo requesting that filming be brought forward by two weeks since Newman had decided to order the recording of an experimental first episode for the series. The intention behind this move was that if this was deemed successful it would form the first transmitted episode scheduled for Saturday 24 August, and should it prove unsuccessful or problematical, there would be two clear weeks remaining in which to resolve any technical problems.

By the end of the month of May 1963, the Doctor Who production team was assigned an additional member to fill the slot of Associate Producer. The person chosen was Mervyn Pinfield, who had worked within the BBC television service since the early days of the nineteen-thirties and was an acknowledged expert in technical matters.

Pinfield's primary function on the new series would be to co-ordinate and advise on the complex technical aspects of Dr. Who, a task for which he was considered the perfect choice by dint of the fact that he had already gained a considerable body of experience with the subject matter, having directed The Monsters the previous November.

By the beginning of June 1963, Rex Tucker had turned his attention to the all-important task of casting by asking the actor Hugh David if he would be interested in taking on the role of The Doctor. David declined the offer on the grounds of the discomfort of a high public profile, something which he had gained during a period as a regular cast member of the Granada Television series, Knight Errant.

Anthony Coburn, by this time had started work on what was expected to be the series' second serial. Coburn's story was to be a four-part adventure which would see the Doctor's ship travelling far back in time to the Stone Age.

On Tuesday 4 June Donald Wilson sent Newman a detailed synopsis for Bunny Webber's proposed first story, The Giants, and by Friday 7th Newman had read the outline and made handwritten annotations, before returning the synopsis to Wilson. His comments in the attached memo were less than encouraging, "the four episodes," he noted, "seem extremely thin on incident and character" he then noted that in his considered opinion Webber had: "forgotten that his human beings, even though miniscule, have normal sized emotions."

The memo then went on to note that Webber had employed certain story elements which would not sit well with Sydney Newman's philosophy towards science-fiction: "Items involving spiders etc. get us into the B.E.M. (Bug Eyed Monster) school of science-fiction, which, while thrilling, is hardly practical for live television. What I am afraid irritated me about the synopsis was the fact that it seemed to be conceived without much regard for the fact that this was a live television drama serial. The notion of the police box dwindling before the policeman's eyes until it's one-eighth of an inch in size is patently impossible without spending a tremendous amount of money."

Newman agreed. He wrote: "I implore you please keep the entire conception within the realms of practical live television." Despite using the term ‘live television’, Doctor Who was always planned as a recorded programme. However, to keep costs as low as possible, it was to be shot as if it was a live production, with as few recording breaks as possible.

Ultimately, however, based on the draft scripts written by Webber for the first two episodes of The Giants, Donald Wilson and Rex Tucker decided to reject the story on the ground that the technically ambitious effects would be impossible to realise. At this stage in proceedings the cancellation left only a short amount of time remaining before recording was due to begin. Wilson took the decision to move Anthony Coburn's prehistoric tale from second story to first. Wilson then asked Coburn to adapt his story's opening episode reflect this.

Despite the progress being made by the core group in bringing Doctor Who to screen, elsewhere within the BBC there was a certain amount of resistance. This can be highlighted by a memo from Head of Drama Design, Richard Levin, sent to Joanna Spicer, which strongly protested at the demands that would be placed on his department by the new series:

"So far there are no accepted scripts for the series - at least if there are we have not seen any. The designer for the series - and I have no substitute - does not return from leave until Monday of Week 26 and I am not prepared to let him start designing until there are four accepted scripts in his hands. The first filming cannot take place within four weeks of this. I also understand that the series requires extensive model-making and other visual effects. This cannot be undertaken under four weeks’ notice and, unless demands are withdrawn, I estimate the need would be for an additional four effects assistants and 400sq. ft. of additional space."

Levin closed the memo with a somewhat damning verdict: "To my mind, to embark on a series of this kind and length in these circumstances will undoubtedly put this department in an untenable situation and, as a natural corollary, will throw Scenic Servicing Department for a complete 'burton'. This is the kind of crazy enterprise which both Departments can well do without."

Acting on Levin's objections, Ayton Whitaker dispatched a memo to the Assistant Head of Drama Group, Norman Rutherford, -Newman's deputy- due to the fact that by this point both Newman and Donald Wilson were away on leave. In the memo Whitaker recommended that if the fledgling series' previously planned production requirements were unfeasible, the Drama Group should consider no further compromise in its efforts to meet the agreed date of 24 August for the first transmission but should instead "ask for postponement...until such time as we are ready."

With all this hanging in the air, the arrival of Doctor Who's newly appointed permanent producer, was particularly timely. Newman himself, following the rejection of the job by his original choice, Don Taylor, had made the appointment. Newman would later recall the new arrival was exactly the kind of young, go-ahead person he wanted in charge of the series: "When Donald Wilson and I discussed who might take over the responsibility for producing the show I rejected the traditional drama types who did children's serials and said that I wanted somebody who'd be prepared to break rules in doing the show. Somebody young with a sense of 'today' - the early 'Swinging London' days."

That somebody was a person who had earlier worked with the Canadian as part of his Armchair Theatre staff at ABC. Her name was Verity Lambert and at 27-years-old she became the youngest producer at the BBC. "She had never directed, produced, acted or written drama but, by God, she was a bright, highly intelligent, outspoken production secretary who took no nonsense and never gave any." Newman stated. "I introduced her to Donald Wilson and I don't think he quite liked her at first. She was too good looking, too smart-alecky and too commercial television minded. I knew they would hit it off when they got to know one another better. They did." Taking up residence in her new fifth floor office at Television Centre, Lambert quickly became acquainted with the progress made so far. She wasn't thrilled with what she saw. "Had I been there at the point of commissioning I would probably not have chosen that story. I thought it was a very difficult and dangerous one to start with. It's hard to invest reality into people running around with clubs making funny noises." Lambert even, for a time, tried to find a replacement script.

On Monday 24 June the last key member of the production team was appointed in the form of David Whitaker. Having spent six years on the staff of the Script Department, Whitaker had most recently been responsible for Sunday plays, and was already familiar with the background to Doctor Who. As script editor he would now have a major input towards the development of the story and the characters. Whitaker’s actress wife, June Barry, would remember the work her husband did on the series. "David crafted and shaped Doctor Who" she would claim. "Sydney and Donald evolved the frame, but the myth came from him. He worked harder on the show than anyone else, steering many of the writers he brought into Doctor Who. And he created far more than he is ever given credit for."

By this time Coburn had begun re-crafting the central companion characters for the series. Sue became Suzanne and Cliff was renamed Ian Chesterton. In a memo to Lambert, David Whitaker referred to a rewrite that Coburn had been asked to carry out. "Tony has improved episode one very much - particularly regarding Chesterton. I have discussed the whole business with him, and we have agreed he shall push on and finish all four scripts. Tony has inserted some details about Suzanne regarding her own existence. Doctor Who, as you will read, tells that (or hints that) Suzanne has some sort of Royal Blood. This gives Doctor Who and Suzanne good reason to leave their own environment. Of course, I think we must discuss this carefully with Tony when we go through the scripts with him." Regarding the character of The Doctor, Whitaker noted "I feel that he should be more like the old professor that Frank Morgan played in The Wizard of Oz, only a little more authentic. Then we can strike some of the charm and humour as well as the mystery, the suspicion, and the cunning. Do you agree?"

Verity Lambert then met with Richard Levin and got him to back down from his previous stand and agree that design work could go ahead on the two scripts available, given that no new sets would be required for episodes three and four. However, they were unable to agree the planned production dates and as a result of this the pilot episode would now be shot on Friday 22 September.

Rex Tucker had already begun auditions for the main characters of Suzanne and Miss McGovern, but given the delay, Tucker would no longer be able to direct The Tribe of the Gum (which was Coburn's working title for the story). Actresses who auditioned for the part of Susan at this time were Maureen Crombie, Anna Palk, Waveney Lee, Heather Fleming, Camilla Hasse and Ann Casteldini. Also considered, but not seen were Anneke Wills and Christa Bergman. For Miss McGovern – Phillida Law, Penelope Lee and Sally Holme were seen. “The only part I advised on,” said Rex Tucker “was for the role of Suzanne. I saw an unknown young Australian actress, whose name I forget, who had only just arrived in the country who I believed would be ideal for the part. I then went on holiday and on my return discovered that both Sydney Newman and Verity Lambert had replaced my initial choice, which I thought rather strange.”

In an attempt to avoid further confusion over the series characters, a writer’s guide was prepared by Wilson, Webber and Newman, and during the course of this Miss McGovern was renamed Barbara Wright and Suzanne was now given the name of Susan Foreman. It was Coburn's suggestion that she was to be The Doctor's granddaughter.

The writer's guide gave the following profile of the lead character: DOCTOR WHO: A name given to him by his two unwilling fellow travellers, Barbara Wright and Ian Chesterton, simply because they don't know who he is, and he is quite happy to extend the mystery surrounding him. He is frail looking but tough like an old turkey and this is amply demonstrated whenever he is forced to run away from danger. He can be enormously cunning once he feels he is being conspired against and he sometimes acts with impulse rather than reasoned intelligence.

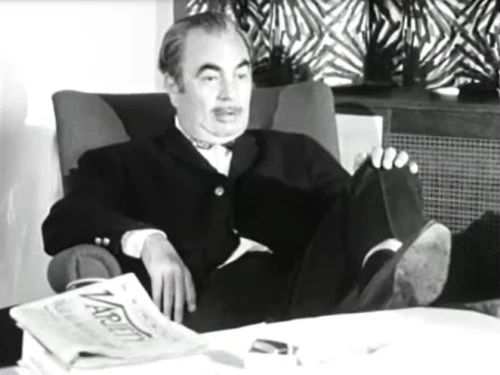

Unhappy with Tucker's choices of actors, Verity Lambert undertook the job of casting The Doctor herself. Actors considered for the role were Cyril Cusack and Leslie French. Eventually, Lambert decided to approach 55-year-old character actor William Hartnell.

Although he was initially reluctant to take it, his agent (his son-in-law Terry Carney), suggested to Hartnell it might be just the type of role to break him out of the typecasting he had come to believe he’d fallen foul to (see William Hartnell’s biography). He took a copy of the first draft script to Hartnell's home near Mayfield in Sussex and after reading it Hartnell agreed to meet up with Verity Lambert and director Waris Hussein who convinced him to take the part.

"...my son-in-law approached me about playing the part. I hadn't worked for the BBC since steam radio twenty-five years ago and I didn't fancy the idea of returning to state control so late in life. …The part required some thought, unlike The Army Game and most of the other rubbish I've been associated with in the past. I've not been offered the sort of work I've wanted due to past disagreements I've had with producers and directors over how parts should be played."

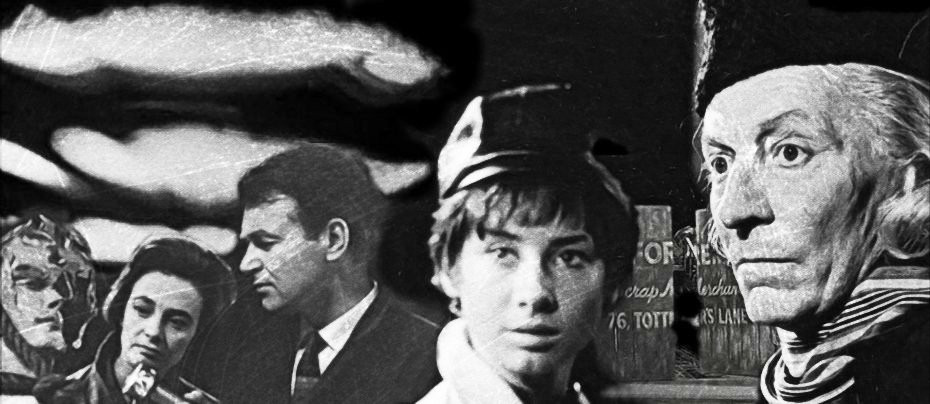

The role of Ian Chesterton went to William Russell who was well known for his portrayal of Sir Lancelot in the Sapphire Film series The Adventures of Sir Lancelot (the first British series to be made in colour). Jacqueline Hill, an old friend of Lambert's was cast as Barbara Wright and Carole Ann Ford was cast as Susan.

By the end of the month Verity Lambert had commissioned Ron Grainer, a top BBC composer who had written the themes for Maigret and Steptoe and Son, to write the theme music for Doctor Who. On 20 August the first filming for the series opening title sequence commenced. The sequence had been designed by Bernard Lodge of the BBC Graphics Unit and made use of a technique known as howl-around, which involved pointing the camera at a screen displaying its own output and filming the resulting patterns. In September the series regular cast got together for a photo-call at television centre, and the following day (21st), rehearsals began in earnest. On Friday 27th the opening episode, An Unearthly Child, was recorded in Lime Grove Studio D.

For years the first episode has been incorrectly referred to by some as the ‘Pilot Episode.’ William Russell made it quite clear when he said “…our first pilot was not a pilot – it was an attempt to get it right first time.” Three days later Sydney Newman viewed the tape of the first recording. As a result of this Newman told Verity Lambert and director Waris Hussein that the pilot was unacceptable for transmission and would therefore have to be remounted. This took place on Friday 18 October.

With the unprecedented remount of the pilot deemed to be a success by the exacting Newman, Doctor Who's first televised adventure became a reality. A reality which not only justified the faith and commitment of all concerned in its creation, but also stands even today as a worthy monument to the skill, creativity, and determination of the dedicated group of people who had lovingly nurtured the fledgling series from initial concept to eventual broadcast.

In the slow and not always smooth progression from vague concept to its ultimate status as an immensely important televisual icon, Doctor Who stands as a proud and eminently worthy monument to the too often forgotten and unsung individuals who ushered in the birth of that legend.

Through their combined efforts magic was woven, wonder brought forth and imagination allowed free flight. Through their combined efforts, and the stewardship of those that followed in their footsteps down the decades, a simple Saturday evening serial for all the family grew into a national institution whose motifs have intertwined themselves into the very core of the national consciousness.

Sources of reference:

BBC Archives

The Doctor Who Handbook – The First Doctor by Howe-Stammers-Walker published 1994

DWB interview with Sydney Newman by Tim Collins and Gary Leigh – August 1986

Interview with Rex Tucker by Paul R Jackson - Doctor Who Magazine Issue 221 1995

Various Internet sources

Published on January 21st, 2022. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.