Rising Damp - All Around the House

Article by Andrew Cobby

There were two general elections in the UK in 1974. This was also the year that Rising Damp was first broadcast. I don’t know much about politics (I can’t do, I vote Labour) so I’m devoting this piece to Rising Damp.

It had a couple of great musical hooks to lure the unsuspecting viewer onto its premises - the five-note fanfare of Yorkshire TV and the jaunty rag-style piano theme tune. I don’t know who is playing the theme but I always imagine it to be Bobby Crush, still warm from his success on Opportunity Knocks, wearing a velvet suit and one of those shirts with a ruffle on the front.

The ident proudly announced a ‘Yorkshire Television Colour Production’ but such a boast meant nothing to us because we still had a black and white telly in 1974. Ever hopeful, I asked my dad ‘Does that mean we can watch it in colour?’

‘Fraid not’, my dad replied, ‘but give it another couple of years and who knows?’. Talk about managing a kid’s expectations. I shouldn’t be too unkind to him. Dad must have put in a lot of overtime that year because we got a brand-new colour TV a year ahead of schedule, just in time for the 1975 FA Cup Final. Unfortunately, Joseph and his Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat didn’t reach the final that year so we couldn’t get the full benefit. Instead we got Fulham, in glorious black and white. I don’t know how much my dad paid for the colour set but I think he should have got himself back down to Rumbelows and demanded half his money back.

Viewers like to use term ‘season’ now to describe a bundle of episodes but this is too grand a title, too reminiscent of sprawling American TV shows that take up most of the calendar. There are only 28 episodes of Rising Damp - four batches of six or seven episodes apiece plus a Christmas special tacked on to the end of batch two. So, as far as Rising Damp is concerned, ‘series’ it is.

It started life as a stage play, The Banana Box , in 1970. Its title is an implied examination of identity - ‘If a kitten is born in a banana box, does that mean it’s a kitten – or a banana?’

In the stage play, the main character was called Rooksby and was played by Wilfrid Brambell. The name was changed to Rigsby for the TV series. Rooksby suggests a man with a tendency to defraud, overcharge or swindle so perhaps ITV wished to soften the character’s edges a little to make for more palatable viewing at 7.30 in the evening.

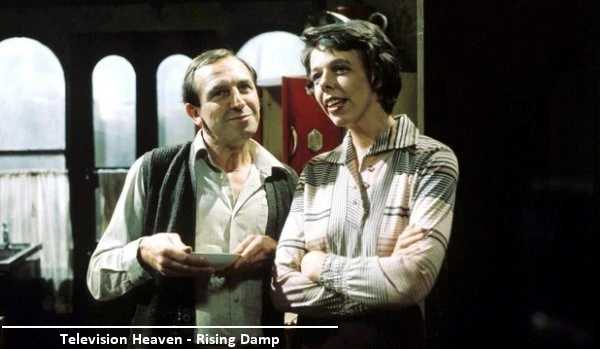

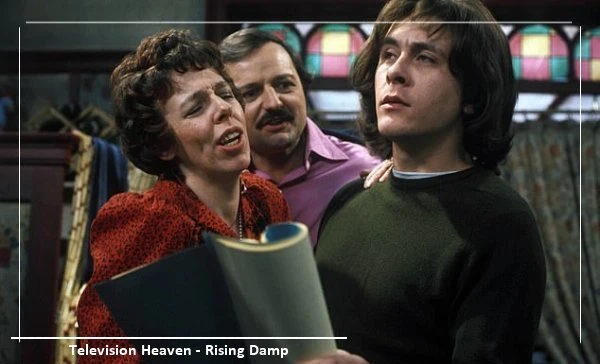

In summary, Rising Damp concerns landlord Rupert Rigsby and the tenants in a run-down boarding house. The main tenants we see are Ruth Jones, a fey university administrator, Alan Moore, a shy and virginal medical student and Philip Smith, a not-so-shy-and-virginal student of town planning who claims to be the son of an African chief. It doesn’t sound much, does it? To be honest, in some episodes, it wasn’t.

The early 1970s were challenging times for people of Rigsby’s generation. For them, the Second World War was still within touching distance but their place in the world was being questioned by membership of the European Economic Community, immigration and a younger crop of men and women for whom the war was something experienced second-hand through their parents.

Rising Damp has an airless atmosphere with no exterior shots. Doubtless this is due to budgetary constraints but it also emphasises how constricting it sometimes feels to live in close quarters with other human beings. Even Porridge, set in a prison, has the occasional exterior shot of the exercise yard or the wilds of Cumbria. Sometimes a prison doesn’t have to have grey bars around it.

The precise setting of Rising Damp is undefined but there are enough clues to suggest that the action takes places somewhere in Yorkshire. I like to think of the boarding house based somewhere in Hull in the East Riding, surviving in splendid isolation on the Humber. Perhaps to seek a location is to miss the point because how do we know the residence hasn’t broken free of its moorings and drifted off? The hermetically-sealed house could be on a voyage to the bottom of the North Sea and no-one would be any the wiser.

In the TV series Rigsby is played, of course, by Leonard Rossiter. If the lovely Yorkshire Television ident and the Rising Damp rag don’t grab you, watch it to see him. He is an actor who I don’t think has been replaced since his early death at the age of 57 in 1984.

For all Mr Rossiter’s gifts, and the difficulty of getting past the character of old man Steptoe, it would have been wonderful to see Wilfrid Brambell’s interpretation of Rigsby.

You can see both of them together in the Steptoe and Son episode The Desperate Hours. Mr Rossiter puts in a guest appearance as an escaped convict who hides out in the Steptoe residence and, hindered by his elderly accomplice, is made to feel young Harold’s pain.

Mr Rossiter brings an almost manic energy to the role of Rigsby (the sweat patches under his arms are a dead giveaway). Clad in an old cardy while lamenting his unrequited love for Miss Jones, he was an instantly recognisable figure. Along with Franks Carson and Spencer, the character was a reliable source of material for impressionists everywhere.

I’ve often wondered why impressionists did impressions of fictional characters like Rigsby, Frank Spencer or Dame Edna Everage. Politicians or other real-lifers with egos for pricking are fair game but I‘ve always thought that lampooning a figure created by someone else robs an impersonation of its potency.

While I’m on the subject, I watched an old Mike Yarwood show recently. I have no axe to grind with Mr Yarwood but, if he was the best we had, I wouldn’t care to imagine what the others must have been like.

Leonard Rossiter invests the landlord with a likeability that perhaps he doesn’t deserve. After all, he is obsessed with status, has racist views, lives in the past (though some would say there’s nothing wrong with that) and, with respect to Tory voters, votes Tory.

It’s surprising, or maybe it isn’t, how the separation of a TV screen brings us closer to characters we would cross the road to avoid in real life.

The racist views that he sometimes airs are unacceptable now (and to think they were spouted at peak viewing time). The joke is on Rigsby, of course. It’s Philip that Miss Jones lusts after (as well as Desmond, Gwyn the Theology student, Hilary the actor, Mr Platt the prospective Liberal candidate...) not Rigsby and, in A Night Out, it’s Philip who is acknowledged and greeted by the head waiter as a valued customer.

The head waiter is an old acquaintance of Rigsby’s with whom he has an antagonistic exchange. Rigsby yearns for the past but he seems to have a combative relationship with most people from his own. His accusation that, during the war, the waiter and his father used to fleece American servicemen unfamiliar with pounds, shillings and pence, is a cynical response to the belief that the Second World War was a time when we all stuck together. We’re all in this together, OK? Well yes, but some more than others.

Philip Smith is played by Don Warrington who displays fine, deadpan comic skills as he plays up to Rigsby’s racist views before reducing them to ridicule.

Rigsby refers to Philip as Monolulu. I was unaware of who Monolulu was so I called in Inspector Google to investigate. He was a colourful African prince who would sell tips to unsuspecting punters, having lured them in with his cry of ‘I’ve gotta horse’. This is also the title of a 1965 movie starring renowned rocker and animal-lover Billy Fury so the phrase must have been familiar to cinemagoers of the time. Monolulu is unremembered now. How fleeting one’s fifteen minutes of fame is but I suppose that’s the point.

Monolulu’s past was unknown and largely manufactured by the man himself. Surprise, surprise, he wasn’t really a prince. Rigsby’s mistrust of Philip is well-placed. It is not mentioned in the TV series but the film version reveals that Philip is not an African prince at all. He is an ordinary civilian, on the run from married life in Croydon. Perhaps his claims to be an African prince are a reaction to Rigsby’s prejudices or perhaps he really does enjoy pretending to be African royalty. Or then again it could be our old friend, a little bit of both.

Rigsby has a healthy mistrust of others and his mistrust of Philip is intensified as he sees him as a rival for the affections of Miss Jones. In Philip’s case, his mistrust is so healthy that it could run a marathon and then play a rigorous game of squash afterwards.

A Body Like Mine makes good use of this fitness by having Rigsby and Philip follow a regime which ends with a boxing bout between the two for a night out with Miss Jones. It is clear who she is rooting for. Her cry of ‘Go in and kill him, Philip’ gives the game away. Rightly or wrongly, Rigsby’s perception of the truth is that Miss Jones will tire of Philip before realising that Rigsby is the man for her.

So desperate is he to lose the fight that Philip forces his head against Rigsby’s gloved fist and knocks himself out.

Younger viewers can experience their own Monolulu moment at the end of this episode.

‘Can you ride tandem?’ says Alan, giving a banana to Rigsby who’s bent double after his back seizes up. It’s the punchline to a PG Tips advert depicting the chimp version of the Tour de France. Dressing chimps up as humans to flog packets of tea would be distasteful now but the adverts will be instantly recognisable to viewers of a certain age. Whenever I have a cup of tea I always think of the line ‘You hum it son, I’ll play it’. It doesn’t even have to be PG Tips either, or tea for that matter. Any cup of liquid refreshment has the same effect.

In the Christmas episode, For the Man Who Has Everything , due to misunderstandings that exist only in the world of sitcoms, Rigsby thinks that Philip has made a present to him of a black girl. Perhaps I am being too generous to the 1970s but, even in those benighted times, this plot device would surely have been beyond the pale. And did we ever really laugh at Lily of the Valley?

In Black Magic, Philip dons a leopard skin and bangs a spear three times on the floor while in Charisma, he gives Rigsby a piece of wood from his wardrobe, tells him that it comes from the love tree and advises Rigsby to burn it to attract Miss Jones.

Also in Charisma, Rigsby is ridiculed when he suggests to Alan that he should get a tattoo to make himself appear more attractive to women. At the time, tattoos were worn only by squaddies, jack tars and ne’er-do-wells. Tattoos used to be a symbol of exclusion, now they appear to be a cry for acceptance. How times change.

Charisma has much to recommend it. It is home to a great scene in which a dosed-up Rigsby tries to woo Miss Jones with a bit of Matt Monro played at the wrong speed and there’s a wonderful turn from Liz Edmiston as Maureen, Alan’s eccentric bicycle belle.

Rigsby mellows towards Philip throughout the four series. It doesn’t come as a Road to Damascus style revelation but it does gradually dawn on Rigsby that, despite his apparent exoticism, Philip is just like the rest of us.

Rigsby has a yearning to do better for himself but fails miserably in his attempts. As Alan points out in Stand Up and Be Counted , he’s a social climber. Tellingly, Rigsby doesn’t deny it but laments that the only person down the Conservative Club who speaks to him is the bloke who washes the glasses. Rigsby has a point. After donning the blue rosette in support of Tory candidate Colonel De Vere-Brown he is rewarded by the candidate condemning the boarding house as the unacceptable face of capitalism.

The Labour candidate in this episode goes unnamed. He did have a name the first time it was broadcast but a Labour MP with the same surname objected to the characterisation. In subsequent airings, the character’s name has been erased from the dialogue, the credits and the Vote Labour poster.

I don’t know why the honourable member of parliament should object. The character is played by Michael Ward, a pleasingly flamboyant actor who always seemed to enjoy his work. Whenever I see the episode now, I cheer him on. Go on Michael, have a good time, be as theatrical as you like. Not that this estimable actor needed any encouragement to do that.

Richard Beckinsale plays a naïve character here, similar to the one he played in The Lovers and Porridge so I don’t think the role of Alan, the frustrated student, was much of a stretch for him. Had he lived, it would have been instructive to learn whether he would have been able to play other types of roles. The brief clips I have seen of Bloody Kids, the Stephen Frears film he was working on when he died, suggest he would. There is a definite menace, and no naivety at all, in his appearance as a roundhead of a policeman.

In 1977, at the age of 30, Mr Beckinsale had an episode of This Is Your Life all to himself. This would seem to be a ridiculously young age to evaluate someone’s life but perhaps the show’s producers knew something the rest of us didn’t.

I remember when his death was reported on the ITN News at 5.45. His picture appeared just over the left shoulder of the newsreader and I can still recall those couple of seconds before the announcement of his death at the age of 31. I don’t know what I was thinking when I saw his photo pop up on that March day in 1979 but I know for definite that I didn’t think he had died.

It might be time to reappraise Bloomers, his final sitcom set in a florist’s shop which was shown posthumously by the BBC in 1979. In similar vein, I would like to see again two lesser-known Leonard Rossiter vehicles – The Losers and Tripper’s Day. I don’t remember either of them being all that good but the intervening years may have been kind to them. I think most episodes of The Losers may be missing, believed wiped which is unusual for a series made as recently as 1978. Could it have been so bad that it was wiped deliberately?

Years ago, I watched Leonard Rossiter on the Russell Harty Show and I was disappointed with how ill at ease, humourless, pompous even, he appeared to be. But he was a serious, talented man who was well aware of how gifted he was.

There’s a story, possibly untrue, that he referred to Joan Collins, his co-star in the famed Cinzano adverts, as ‘the prop’. The story goes that it was a half-joking reference but when something’s half-joking it’s also half-serious.

I doubt whether Mr Rossiter would have dared to refer to Frances de la Tour in similar terms. As Ruth Jones, Miss de la Tour had a talent to match his. I suspect they both knew it too, which might partly explain the reportedly frosty relationship between the two.

She gives a great performance, particularly in those moments where she almost absent-mindedly reminisces about traumatic events from her past. In All Our Yesterdays, her wartime experience consists of an unlikely tale of a pram-bound Miss Jones and mother being machine-gunned coming from the vicarage by a Messerschmidt. This episode is really an excuse for Rigsby to show off his war trophies, but it benefits from an appearance from Derek Newark as the wrestler Spooner. Laid up with a broken leg, he drives the other residents to distraction by playing his radio at a high volume. He seems humourless at first but he reveals a sense of humour by joining in with the others when Rigsby thinks he has shot him.

She tells another tale in Pink Carnations, explaining that her frown is the result of an insecure pushchair with a dodgy wheel that kept coming off and throwing her into the road. Funniest of all is the one she recounts in Black Magic about the untimely demise of her father. The tales paint a picture of the fey eccentricity of Miss Jones. They also reveal a sadness.

Miss Jones leaves the show for four episodes in series two for a liaison with Desmond. In Moonlight and Roses, it is revealed that Desmond is a librarian who hangs about the poetry section all day and has got all the chat. At least, that’s Alan’s take on him. Desmond is the type of man that other men are wary of, which is probably not unconnected to the fact that women can’t resist men like him.

Rigsby’s reaction to the librarian is more succinct - ‘Desmond?’ he says, ‘Bloody Desmond?’, his effeminate intonation revealing that he sees him as no threat in his pursuit of Miss Jones. This episode contains a funny scene in which Ruth and Desmond are entwined by the front door, with Alan spying on them with a pair of binoculars.

‘Just one more kiss’ says Desmond, ‘before my bus comes’ followed by an anxious glance over his shoulder. We might be looking at the stars but our leaden feet are solidly planted on terrafirma. Anyway, praise should go to the ever-dependable Robin Parkinson as Desmond Bloody Desmond. It’s only a small role but it’s made memorable by Mr Parkinson.

While she’s away with Desmond, Ruth’s place in the house is taken by Brenda, an artist’s model. She’s more worldly than Ruth and is all too aware of Rigsby’s intentions towards her. There’s a marvellous moment In Things That Go Bump in the Night when Rigsby accidentally brushes against Brenda’s chest. ‘Quite firm’ says Rigsby, half to himself. I’ve always liked this line. I can’t decide if it’s an ad lib. If it is, Mr Rossiter deserves credit for it. If it isn’t, he still deserves credit for making it sound as if it is. It’s all in the delivery, isn’t it?

Norman Bird appears in this one as a vicar who, with his cricket loving curate Gordon, is called in to exorcise the house. He makes liberal use of the refained ‘Mr Rigsbays’ (count ’em) but he’s always a class act. I could watch Norman Bird all day.

Brenda is played by Gay Rose. I was never really convinced by Brenda. If you listen to her diction it sounds as if she’s straining to convey a southern English accent. That’s because Ms Rose is Canadian, which I didn’t know until recently. According to IMDB, Ms Rose returned to Canada which probably explains why I haven’t seen her in anything else.

UK Gold occasionally rerun Rising Damp Forever, a surprisingly thoughtful two-part documentary on the making of the series. Don Warrington features prominently, and quite rightly as the show is something to be proud of, but the documentary also takes the time to interview writer Eric Chappell, the producer Vernon Lawrence, Judy Buxton and Christopher Strauli (he played Alan’s replacement in the film version).

It’s a pity that Frances de la Tour didn’t make an appearance. She is a serious theatre actor so it may be that she doesn’t see why she should discuss an ITV comedy programme made years ago. All the same, since Rising Damp she has made infrequent forays into TV comedy with shows like A Kind of Living, Every Silver Lining, Big School and Vicious. The one thing they have in common as that they were nowhere near as memorable as Rising Damp (I haven’t seen any documentaries extolling the virtues of any of them, have you?) Miss de la Tour should follow the lead of Don Warrington and be proud to have been part of it.

It would have been nice to see Norman Bird make a return appearance as the clergyman in the disappointing Fawcett’s Python. This time the vicar is played by Jonathan Elsom, rather in the manner of Derek Nimmo, who nevertheless provides the episode’s funniest moment when rehearsing a dirge accompanied by Miss Jones on the recorder.

The disappointment with this episode comes from some terrible acting by Andonia Katsaros as the exotic dancer, the criminal under-use of Miss Jones and, unusually, the over-acting of Leonard Rossiter.

I don’t feel comfortable watching his self-indulgent delivery of the line ‘He’s got hold of me!’ when he puts his hand in the snake’s basket and the wrestling match behind the sofa with the snake. I don’t feel comfortable because it’s so unfunny.

A similar example of ham can be found in Pink Carnations . Leonard Rossiter is undeniably funny in the pub scene but his comic gurning, physical comedy with the bar stool and the beer mats suggest a man going through the motions. He knows which comic buttons to press and he’s pressing them without giving it too much thought.

It is a very amusing scene with farcical misunderstandings stemming from the pink carnations that Rigsby and Miss Jones, oblivious both, have agreed to wear to recognise each other on their date. Mr Rossiter is more restrained in the earlier episode, A Night Out, with a similar setting and is all the funnier for it.

He was capable of producing great physical comedy. In The Cocktail Hour, Rigsby explains to Alan how to enter a room with panache. He does it once, giving a running commentary of his actions but it’s even funnier the second time he does it, giving a more clipped commentary as he goes. The afore-mentioned Judy Buxton appears in this episode as Alan’s upper-class girlfriend Caroline. The only other thing I have seen her in is an episode of The Sweeney called Bait. It features George Sewell who has a big, dumb friend who likes rabbits. I think Regan and Carter should have been on the trail of the writers in this one because that’s a blatant steel from Of Mice and Men.

TV is a small, incestuous world. George Sewell appears in the Rising Damp episode The Prowler as a police detective who turns out to be a villain who runs off with Rigsby’s hard earned savings. Mr Sewell usually played a policeman or a criminal and this episode allows him to stretch his acting muscles by playing both.

I think perhaps, in the end, Leonard Rossiter got bored with the role. In the final episode, Come on In, The Water’s Lovely, Miss Jones finally gives in and agrees to marry Rigsby. Don’t worry, due to droll misunderstandings, they don’t wed and Rigsby is destined to see out his days without the love, or at least companionship, of Ruth Jones. Or is he?

The series ended in 1978 but I don’t know if plans for future series had to be abandoned after the death of Richard Beckinsale. Philip being a married man from Croydon was revealed in the film version but maybe the writer intended to keep this bombshell up his sleeve for series five. But this is all supposition on my part, your Honour.

The first two series are as good as anything you’ll see anywhere. The second two are a more hit and miss affair (Richard Beckinsale doesn’t appear in the final, fourth series and he’s sorely missed).

Even the weaker episodes have bits worth savouring. Fire and Brimstone, from series four, is a lack-lustre instalment in which John Clive, as Welsh theology student Gwyn, encourages Rigsby to find God. The episode’s saving grace is the very funny scene in which Rigsby and Miss Jones partake of an intimate fish supper washed down by some white wine.

Rigsby thinks his luck’s in and tries to persuade Miss Jones to join him in a dirty weekend to Yarmouth for a better-quality piece of cod. Miss Jones almost weakens and tells Rigsby that he looks strangely fascinating while he quietly chokes on the smoke inhaled from his cigar.

The originality of the plots was never one of the show’s strong points but the final batch of episodes seem more disjointed as different guest actors are brought in each week to try and fill the void left by the departure of Richard Beckinsale. Some of the guest actors like John Clive, David Swift and Peter Jeffrey seem to shout a lot. Perhaps it’s an actorly ego thing – they realised they were up against Leonard Rossiter and decided that they had to up their game. Whatever the reason, it comes across as over-acting.

Of the guest stars in the last two series, I think only Peter Bowles manages to keep up with Mr Rossiter. He appears in Stage Struck as the camp actor Hilary and very good he is too. He is not as camp as he seems because he shows his virility by engaging in a passionate clinch with Miss Jones. ‘He’s not one of them, he’s one of us’ Rigsby says in disgust.

This was just before Mr Bowles’s golden period when he never seemed to be off the telly - To the Manor Born, Only When I Laugh , Lytton’s Diary, Rumpole of the Bailey, The Irish RM, The Bounder.

The Permissive Society is a great episode, one of the best of series three. It contains one of my favourite lines from the whole of sitcom. Alan has admitted to not being as experienced as he makes out, which leads Rigsby to protest that Alan was supposed to know where the erogenous regions are. ‘I know where the Himalayas are’ replies Alan, ‘but I’ve never been up’em.’

Sometimes words can be so unintentionally revealing of character that they leave you stranded in a no-man's-land between funny and sad. The legacy of this line is that, whenever I see a news item about latest intrepid climber to conquer Everest, I always think about the lies that Alan Moore told about his sex life and try not to think about the lies that I’ve told about mine.

The episode is memorable for Rigsby’s spirited defence of Alan against the insinuations of the great George A Cooper. He quite rightly points out that the permissive society doesn’t exist except in the minds of those who would disapprove of it if it did.

It’s probably the Hull thing but whenever I watch an episode of Rising Damp I think of Mr Bleaney, a poem by Philip Larkin. The poem is a thoughtful study of renting a room which evolves into a reflection on loneliness and what we leave behind when we are gone. It sounds pretentious to say it, but I think the writer Eric Chappell captures the same feeling in much of Rising Damp. I think he does it more consistently in the first two series but he gives the subject just as much thought as Mr Larkin.

So perhaps the most praise should go to the writer because the actors would have nothing to say if it wasn’t for him. Eric Chappell represents, with precision, the life of the residents in their hired boxes. He offers a warts-and-all depiction of how we are and it’s staring right back at us. Most importantly for a comedy, it is funny (at its best, very funny). If it wasn’t, it would break your heart.

Published on June 5th, 2020. Written by Andrew Cobby for Television Heaven.