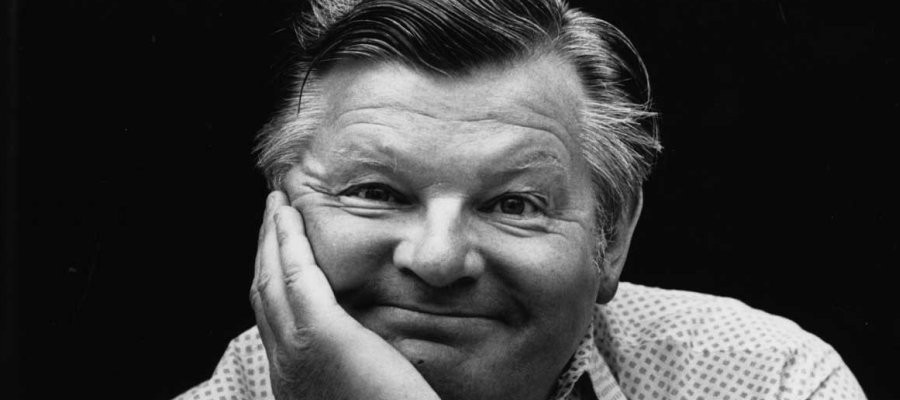

Benny Hill

Benny Hill was born into something of an amateur showbiz background. His paternal grandfather, Henry, had been a street clown, his uncle, Leonard, had performed a circus high-wire act which ultimately cost him his life, and his father, Alfred, had run away from home at the age of sixteen to join Fossett's Circus.

But Benny's father was not said to have been the most pleasant of gentlemen. A number of hardships and missed opportunities left him something of an embittered man with an uncompromising attitude. Because of this he was nicknamed "the Captain", even though he only ever reached the rank of private after his showbiz career was curtailed by the outbreak of World War One.

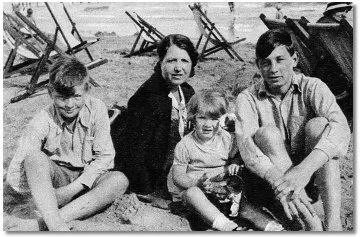

Returning home at the end of hostilities, having been gassed in France and then held Prisoner of War in Belgium, Alfred turned his back on show business and went to work as a clerk. By 1920 he had met and married Helen Cave and the couple settled in Helen's hometown of Southampton. The following year the couple celebrated the birth of their first child, a boy whom they christened Leonard. Benny, who was named Alfred Hawthorne Hill, was born three years later on 25th January 1924 (not 1925 as often stated). A third child, Diana, was born in 1933.

All of the Hill children grew up closer to their mother than their father who it has been said would constantly try to prove that he was stronger, cleverer and more able than any of his offspring. And if Alfred Senior had returned from the war a bitter man then a missed opportunity at work did nothing to mellow his character. Alfred had been offered the chance to buy a partnership in the surgical appliance shop where he worked. He was unable to raise the necessary funds and the business, a backstreet outlet selling abdominal supports, tonics and (mainly) contraceptives, became hugely successful and made its owner, Jack Stanley, a millionaire.

As a child, Benny faced schoolyard taunts from his fellow pupils at Shirley Infant School about the fact that his father sold what was then popularly known as 'French letters'. In order to combat these, the youngster turned to humour and used his father's profession to his advantage by allowing the other children to believe that he was well versed in all matters sexually related. Benny began to indulge in the type of schoolboy smut and saucy postcard humour that would eventually become his trademark. According to his brother, Leonard, one of Benny's earliest jokes went:

Teacher (to latecomer): Where have you been?

Schoolboy: Up Shirley Hill.

Teacher (to late arriving schoolgirl): Who are you?

Schoolgirl: Shirley Hill!

Around this time Benny landed a part in a school play. Years later he recalled: "I was a Guinea Pig in 'Alice in Wonderland.' No costume. I merely wore a card saying what I was supposed to represent. But it was a speaking part. I had to come on the stage and say 'Here, here!'" By this time Benny had already extended his range beyond simple playground comedian. At home he began to impersonate the voices he heard on the 'wireless' and by the age of ten he could do fair impressions of many of the comedians of the day including Max Miller and Rob Wilton. He also began singing in a local church choir.

By now Benny's schoolwork was beginning to take second place to his desire to entertain. "By some fluke," he wrote in 1955 "I gained a scholarship for Taunton School, but I never managed to reach the sixth form. My general feeling about school days are that although I was never classed as brainy, I certainly had fun. And I could always remember what I wanted to remember. Who cares about 1066 and all that?"

From the age of 13, Benny was selling himself around Southampton as an amateur entertainer. His repertoire was still fairly limited and when asked years later what sort of act he did he replied; "Max Miller's!" The following year he landed his first semi-professional engagement with Bobbie's Concert Party. He had two short spots on the show. He then took his act around the working men's clubs where his saucy Max Miller routines were better appreciated.

When the time came for Benny to leave school, at fifteen, he found a job in the local coal company. "They offered me fifteen shillings a week." He said. "For a youngster fresh from school it was not an interesting job; in a small office, overlooking the weighbridge, checking each cart as it came in." The job lasted for just three weeks. Alfred Senior had a friend who was the manager of a local Woolworth's store and it was arranged that Alfred Junior would begin work as a stock room clerk.

He worked at the Woolworth's store for six months. "Before I quit that job it had two big effects on me." He later recalled. "I fell in love and I learned about people."

"The girl I fell in love with was Jean, two years my senior. The romance did not last, because her attitude towards me was one of amused tolerance. 'You make me laugh, sonny boy,' she used to say." What had a more lasting effect though was Benny's observance of the people he came into contact with. "That comes naturally when you work in a chain store," he said, "because you meet thousands of people. Unconsciously, at first, I began to notice foibles and mannerisms. I began to develop a mirror-like memory for faces and voices."

After leaving Woolworth's, Benny took a job as a milkman. "Because of regulations, no milk was delivered before 7.0 am and my day often ended by 1.0 pm. The absolute freedom of the job was the attraction." The rest of the time Benny was 'doing the rounds' of the local concert parties. "Of course I had no real act. I wildly improvised on everything I heard on the radio or saw at the local variety houses." In addition to these 'five-bob' appearances Benny got a job in a semi-pro dance band as a drummer. "This was at the behest of a local music teacher, Mrs Lilywhite, who made me a member of Ivy Lillywhite's Band. I soon began to average 30 shillings a week with concerts and drumming."

At this stage in his career Benny took a major decision. "Was it worth while keeping on with the milk round if I could make 30 bob a week so easily on the stage? I was still going the backstage rounds of the local variety theatres, hoping the comedians would ask me into their dressing-rooms or come out and have a drink with me. I hung on every word they said. At last I found two comedians who listened when I said I wanted a job."

"They were just building up a new act. 'All right, son,' they said. 'We'll give you a start. Now, listen. Next week we play Chesterfield and the week after that we'll be down south again. Leave us your address and we will write to you directly we get back. Then you can start in the act.' I scribbled my address, then went back (to work) the next morning and gave in my weeks' notice." Benny never saw the two comedians again.

Although he had no wage packet to look forward to at the end of the following week Benny claimed that he was not too downhearted. He had saved a little money from his concert performances and his drumming with Ivy Lilywhite's band and with just a little more capital he decided he could take the risk and try his luck in London. "Mum or dad would have lent me the money," he said, "...but it was my own fault I'd given in my notice on the milk-round. So I sold my drum kit for £8.00 and with that I came to London."

Benny arrived at Waterloo Station in September 1940 clutching an envelope on which he had written the names of some famous suburban variety houses -the Metropolitan, Edgeware Road; the Empress, Brixton; the Chelsea Palace. They were just names to him so he stopped a policeman for directions and the kindly bobby mapped out a route for him so he could get to them by bus.

"At the Chiswick Empire they did not want to know about Alf Hill." Benny wrote. "I had much the same reception at the "Met," but at the Chelsea Palace I was lucky enough to arrange to see Harry Benet (a well-known panto and revue impresario of the time) at his office the next morning." In fact it was at the Empress in Brixton that Benny got his first bit of luck. One of the acts there was Sid Seymour and the Mad Hatters. Benny asked for Sid at the stage door and the comedian came to see him. He told Benny that he had nothing for him but suggested the Chelsea Palace where his brother, Phil Seymour, an agent himself, was presenting a show called "Follow the Fun." Although Benny never got to see Phil Seymour he made a suitable enough impression on the theatre manager, Harry Frockton Foster, for an appointment to be made with Harry Benet.

Benny recalled that first day in London; "It was now getting late and I wanted to make my £8.00 last as long as possible. So I bought some fish and chips and slept that cold September night on Streatham Common." The next morning after breakfast and a wash and brush-up in Lyons Corner House cafe, Benny made his way to Benet's office at 11 Beak Street, Soho. Benet was impressed with the young 17 year-old and said, "Alright lad, I'll engage you as property boy."

"And can I play parts?" asked Benny

Benet laughed. "There'll be small parts, too."

"How much?"

"Son," Benet said, "many years ago I started George Lacey at £2.00 a week." (Lacey was the star of "Follow the Fun"). "I'll start you on £3.10s."

Benny started his London stage career a few days later when "Follow the Fun" opened at the East Ham Palace, and in addition to handling all the props he had a one-line part as a policeman. Within a few days though, Benny found himself with a bigger part than he could have imagined.

"One of the stars of the bill was Hal Bryan, and I was behind the back-drop setting props when I heard him out on the stage singing some lines that I had not heard at the first house -'I'm all alone...Wish I had someone to talk to'. At once I cottoned on. His partner had missed his cue, and Hal Bryan was out there in front, alone. I was the nearest, so to save the situation I walked on stage. Hal whispered the lines for the sketch and somehow we managed to get through it." Benny was congratulated by all the cast and crew and as Bryan was leaving the theatre he stuck a 10-shilling note in Benny's hand and said, "You're going to be a trouper, son."

When "Follow the Fun" ended its run Harry Benet retained Benny as baggage master for the panto "Robinson Crusoe" at the Bournemouth Pavilion. "Eventually I worked my wage up to £5 a week," wrote Benny, "and did much work in sketches, usually as feed or straight man. I did not seem to be cut out for comedy in those days."

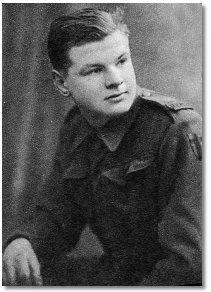

Because Benny was now of 'call-up' age he was expecting to get his papers enlisting him into the war effort. However, because of his wandering life-style these never seemed to catch up with him. Then, in November 1942, the fourth night into "Send Him Victorious" at Cardiff's New Theatre, the military police turned up and arrested him. He spent four miserable nights at Cardiff police station before being marched off to Lincoln Barracks and put to scrubbing floors in the detention room. The next three-and-a-half years were spent in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers where he served in France, Holland, Belgium and finally, Germany.

In the closing stages of the war he was picked for 'Stars in Battledress' and the last nine months of his Army service he spent in Command Services Entertainments. The popular story that the Army discovered him was dismissed by Benny when he wrote: "No, the Army did not discover me. In fact, when I was in Germany with an entertainment unit, the officer in charge took a dim view of my style and insisted on compering the show himself. Most of my time was spent lumbering huge wicker baskets and crates of stage props."

However, not everyone took a dim view of Benny's act and a sergeant by the name of Harry Segal, who had been an old pro of the music halls since childhood spotted something that he liked about Benny's performance. He encouraged a downhearted Benny to persevere and gave him confidence with gentle encouragement. During an outbreak of influenza, which had hit the unit, Segal ordered Benny out onto stage to do a solo act. Among the audience was a Colonel Richard Stone, in charge of Combined Service Entertainment throughout Europe. After the war Stone became Benny's life-long friend and agent.

Benny came out of the Army with a £54.00 gratuity, his de-mob money, and returned briefly to Southampton. But he soon travelled down to London again and decided to try his luck at the capitals famous Windmill Theatre. But during his audition he choked on his first gag and got the dismissive "Next please!" from the theatre's owner, Vivian Van Damm. At the time of this audition he still billed himself as Alf Hill, but decided that he now wanted something that sounded a little more 'up-market.' It was his brother, Leonard, who suggested Benny, Jack Benny being one of his idols. So Alf Hill became Benny Hill.

In the meantime, Benny Hill still had to support himself and he fell back on his old stomping ground of the working men's clubs averaging around one pound a performance. There were very few breaks and even when they came along they paid nothing at all. In 1947 he appeared at the Twentieth Century Theatre in Notting Hill Gate in a revue called "Spotlight", which featured another aspiring young entertainer called Bob Monkhouse. As this revue was a showcase for new talent where agents would come to look at new potentials there was no fee involved for performing there.

Around this time, though, Benny began appearing on radio with great regularity. His first radio appearance was on 30th August 1947 in a variety show called "Beginners Please!" Although the show had a limited audience (it went out at 11.45 on a Saturday morning), Benny's routine was well received by top booking agent Joe Collins (father of actress Joan) and star-maker Carroll Levis. As a result of this Benny was rewarded with a spot on the hugely popular "Variety Band-Box."

It was also around this time that ex-Colonel Stone, now a theatrical agent, reappeared on the scene and worked to get Benny into the professional theatre. His first job was to secure Benny a summer season at the Cliftonville Lido in Kent as a feed for the star turn; Reg Varney. There were two comedians up for the part - Benny and a young man by the name of Peter Sellers. Benny got the part on the strength of an English calypso, which he wrote and performed to his own guitar accompaniment.

The revue that Varney and Hill appeared in was called "Gaytime" and it went down very well with audiences. But the weakest part of the show was Benny's solo spot and he was always uncomfortable performing it. Nevertheless, "Gaytime" did three seasons before the duo were signed up for the touring version of a London Palladium revue called "Sky High". Again Benny's solo was seen as the weakest part of the show and when it arrived in Sunderland Benny was greeted at first with silence, then jeers and finally a slow handclap. Benny walked off the stage completely demoralised. A week later he resigned from the partnership.

After Sunderland Benny was out of work for nine weeks. During this period he spent time writing a number of new sketches, creating new material out of many comic situations that had long been in his mind and then set his sights on the newest medium in entertainment...television.

"I rang up Lime Grove (where the BBC were based) and spoke to Bill Lyon Shaw. We met, and when he had read some of my sketches he got on the house telephone to Ronnie Waldman and said: 'There's a chap here who has some material that may be suitable for TV. Can you spare time to read it?' 'I'll read it now,' said the Head of Light Entertainment, and I was in the Holy of Holies less than twenty minutes after arriving at Lime Grove.

"There was a big bundle of manuscripts on the desk. 'Pick any one you like,' I said to Ronnie Waldman. He thumbed through the bundle, picked a manuscript at random and said: 'Explain it. You read it to me...'"

Benny read through the script and Waldman seemed suitably impressed. "Who do you think would put that type of material over best?" he asked.

"Me!" Benny said.

He smiled: "Maybe you're right."

Then he picked up the telephone and spoke again to Bill Lyon Shaw. Within an hour Benny was booked to appear on TV's "Kaleidoscope."

"Kaleidoscope" was a long running light entertainment magazine that had started in 1946 and was broadcast on Friday nights. Comedy sketches and stand-up routines were a regular feature and during the course of its run a number of British comedians starred in the series and some made their TV debuts. Tony Hancock appeared in "Fools Rush In", his first TV series (a series of extended sketches) in 1951 and Dick Emery made his TV debut in 1952, all under the "Kaleidoscope" umbrella.

Benny had his first sketch 'banned' on this series. In the routine Benny was to play a Customs Officer who was giving a TV lecture, urging all holidaymakers to be good citizens and to declare their nylons and little bottles of perfume. At the end of the lecture the cameraman shouts "Cut! You're off the air." "And about time, too." Says the Customs man as he takes off his cap and wipes the sweat from his brow. As he removes his cap a shower of watches and cigarettes fall out. Pretty tame stuff. But the BBC banned the sketch saying that it would give the false impression that Customs Officers were dishonest.

Almost four years to the day that Benny made his radio debut he headlined his own show on BBC television. "Hi There!" went out on 20th August 1951 at 8.15pm. The 45 minute one-off show, written entirely by Benny Hill and produced by Bill Lyon-Shaw starred Benny and Ernest Maxin in a series of sketches in which Benny played a Frenchman who was bewildered by England, a man baffled by a moving belt in a self service restaurant and three foreign waiters.

It would be another four years before Benny was to get a full series. In the meantime he continued to work regularly on radio and in 1954 he joined the cast for a spin-off series of the hugely successful "Educating Archie." The series, which starred ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy, Archie Andrews, had been the launch pad for the careers of such notables as Bernard Bresslaw, Dick Emery, Bruce Forsyth, Tony Hancock and Sid James. However, when Benny joined the cast Archie's best days were already behind him. The spin-off was called "Archie's the Boy" and was something of an experiment to move Archie out of the classroom and into the real world. It was an experiment that failed and for the next series the original format was revived. Benny did not return.

The BBC agreed that the time was now right for Benny to appear in his own extended TV series. The first edition of "The Benny Hill Show" written by Benny and his writing partner Dave Freeman, was broadcast on Saturday 15th January 1955. The first show was a flop. In an article headed 'Alas Poor Benny', one critic called the show "Ill-rehearsed". "Patchy and lacking cohesion" fired one critic, whilst Kenneth Baily said that Benny had "little new to offer". Benny was taken aback by such criticism, but took heed of the comments and he and Freeman changed the format of the second show. It clearly worked and the following week the critics were full of praise.

Within weeks Benny Hill became a major star. He may have been the first British comedian to be created by television but he took the medium by storm and soon became its master. The televisual methods he employed were nothing short of groundbreaking in their day. In the second show he introduced a spoof quiz based on a panel game called "Find the Link", in which a panel of four guests had to guess the element that the two contestants had in common. In this sketch Jeremy Hawk played the chairman but it was Benny who played all four panellists. By recording all the various sequences separately and then editing them together Benny was able to play Josephine Douglas, Moira Lister, Peter Noble and Kenneth Horne. Today such a trick is commonplace, even old hat, but when first broadcast in January 1955 it was totally new. Benny had found a format for success. Viewers loved to see him parodying other TV shows and mimicking other TV stars. By the end of that first television year he was quite deservedly named Personality of the Year in the Daily Mail National Television Awards.

Although the BBC regarded some of Benny's material as 'near-the-mark' they were not foolish enough to interfere with the format of the shows. Some of the humour was saucy, but it was never overtly offensive and if you understood the innuendo the chances are you were laughing along with it. Also, Benny was hot property and with the new ITV channel about to start in 1955 the Beeb wanted to hold on to every ace in the pack. At that time they didn't have that many.

In 1956 Benny Hill was earning £350.00 per show. By 1957 that had increased to 650 guineas. A 1958 memo from the BBC's head of Light Entertainment, Tom Sloan, revealed that the Corporation's audience research figures revealed that The Benny Hill Show was pulling in an estimated audience of 12 million viewers, and thus they were prepared to pay £1,000 per show. In fact in what was then an unprecedented move, the BBC allowed Benny to record a number of one-off specials for the rival ATV company because they were worried about losing him. Between 1957 and 1960 he recorded eight 'specials' for ATV.

It is near impossible now to judge just how these shows would stand up to the test of time because, as is tragically the case of much British TV archive material the 16mm film was destroyed after it was deemed of no further commercial value.

Benny's success on TV led to offers of West End revue and in 1955 he starred alongside Tommy Cooper in a Bernard Delfont production called "Paris By Night", which ran for twelve months at the Prince of Wales Theatre. But Benny was never really comfortable on the stage, his experience at Sunderland had soured him, even though the year after he became TV's biggest star he returned in triumph to the very theatre where he had been slow hand clapped.

There was also the offer of film work but Benny seemed to have more success in supporting roles than in starring ones. In 1956 he starred in a film called "Who Done It?" written by T.E.B. Clarke. Years later when told by a reporter that the film was going to be televised Benny allegedly said, "In that case I'm taking the next plane to Marseilles." His next film was in 1959, "Light Up The Sky", in which he co-starred with Tommy Steele as part of a musical double act. In 1965 he had a cameo role as the fire chief in "Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines."

In 1968 Benny appeared in one of his most celebrated film roles as the Vulgarian toy maker in the excellent Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. The movie, one of the best loved family films of all time, proved by its longevity and the fact that each generation of children that discover it are captured by its spell, owes more to Benny Hill than most people realise. Despite being credited for the screenplay it has been suggested that Roald Dahl contributed less to the finished article than Benny Hill did. In fact Benny worked for five weeks alongside director Ken Hughes to inject more comic moments into the films scenes, especially the initial ones featuring Caractacus Potts.

Following this Benny made only one other feature film, "The Italian Job", made in 1969 and starring Michael Caine and Noel Coward. As with his previous movie Benny injected a fair amount of humour into "The Italian Job" adding his characters obsession with obese women. But this proved to be his last outing into the world of celluloid. Shortly after "The Italian Job" he abandoned plans for his own screenplay called "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You." Blake Edwards wanted Benny for a cameo in his 1969 film "Darling Lili" starring Julie Andrews and Rock Hudson. Benny even auditioned for it. Apparently Edwards asked Benny if he could do a French accent. Benny, who spoke French fluently, asked "Would you like a Paris accent? East side or west side?" Edwards was not amused and hired someone else.

In 1962 the BBC made a series of 6 twenty-five minute episodes called 'Benny Hill'. In a departure from his usual format this series featured Benny in a sitcom situation in which he played a different character every week. Two more series followed by 1963.

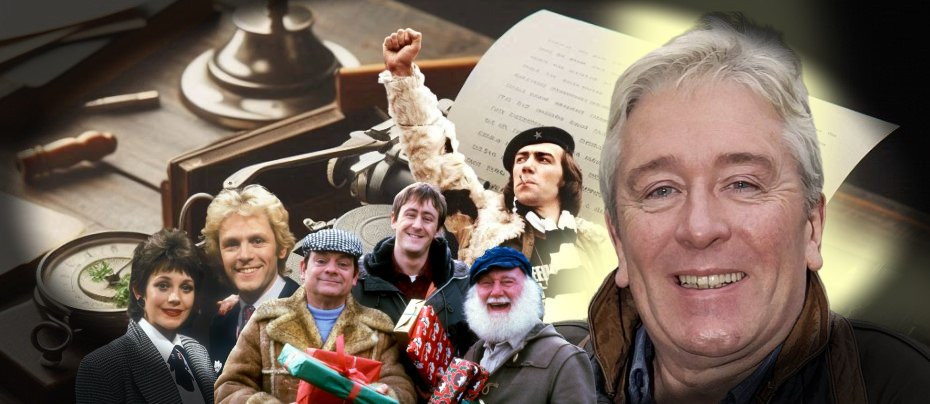

After this Benny returned to his usual format and enjoyed many more successful years at the BBC. But, in 1969 Richard Stone approached Philip Jones, the Head of Light Entertainment at the fledgling Thames Television, and asked if the company was interested in signing Benny to a contract. Jones absolutely jumped at the chance. It was a partnership that saw Benny and Thames win no fewer than 11 major television awards, and more importantly for the star himself, become the first ever British comedian to conquer US television.

One of Benny Hills strengths was that he always moved with the times. Along with the legendary Fred Scuttle, Benny introduced a host of new characters including the Chinaman; Mr Chow Mein. He also correctly gauged public taste by introducing a lot more glamour into his shows, especially with a troupe of girls that would become affectionately known as 'Hills Angels'. Benny's jokes became more daring, the innuendo much 'nearer-the-mark'. The public response was to lap it up. And the higher the viewing figures the more daring the show got. But the permissive age was about to collide head on with a political correctness backlash, and there would be casualties.

Many critics accused Benny Hill of treating women as no more than sex objects, brainless bimbo's whose only justification on his shows was for a bit of titillation and slap and tickle. In fact its fair to say that Benny treated his women with far less contempt than some other British successes such as 'On The Buses' or the 'Carry On' series of films. Benny was well aware of the backlash and immediately toned down the act, dropped the "Angels" and returned to less offensive humour. But the damage had been done.

In 1989 Thames Television's new Head of Light Entertainment, John Howard Davies invited Benny in for a meeting. Having just returned from a triumphant Cannes TV festival Benny assumed that they were to discuss details of a new series. Instead John Howard Davies thanked Benny for all he had done for Thames Television and then sacked him.

Benny had plenty of offers from elsewhere. American television offers came flooding in and he allegedly turned down a $6m offer to make 26 half hour shows in the US because he preferred the security of his home territory. But there were no offers from home. Ideas were tossed back and forth including a series of specials for London Weekend Television, but nothing ever came of them. Benny Hill retired gracefully and with dignity. He was financially secure, in fact he always had a pile of royalty cheques unopened above his fireplace in his Teddington flat, and he took to travelling to his favourite holiday locations, visiting local cinemas and spending time with ex-Angel, Sue Upton, now married and with a family of her own. To her children he was always Uncle Benny.

Fan mail continued to pour in from around the world and Benny aimed to answer every letter personally. In 1991 Thames TV were still making millions of pounds from worldwide sales of the 'Benny Hill Show'. In August of that year he was honoured at the 11th Vevey Comedy Festival in Switzerland with the Charlie Chaplin Award for International Comedy.

By 1992 there were three major television companies vying for Benny's contract. He turned down Thames Television, as well as Carlton (who would eventually replace Thames when the latter lost their franchise), and in the end decided to sign with Nottingham based Central Television. But Benny's health had been suffering for some time. His weight had increased due to overeating and his heart was weak. On 11th February 1992 Benny was admitted to hospital with chest pains. A heart bypass was suggested but Benny turned this down. He was released from hospital after eight days but within hours of returning home he had a relapse.

This time it was diagnosed that he was suffering from kidney failure. Another spell in hospital followed. In the meantime Thames Television, who were continually bombarded with requests from viewers for 'Benny Hill Show' repeats finally gave in and put together a number of re-edited shows. They tore straight into the TV top twenty. A few weeks later on 18th April 1992 Alfred Hawthorne Hill, aged 68, passed away, alone in his flat.

With the passing of Benny Hill, the world of comedy lost one of its greatest clowns. He broke the language barrier in much the same way as his idols; Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin and his impact on a generation can easily be compared with these masters of mirth.

Although the final years of his life were surrounded by controversy his lasting legacy is surely beyond doubt. Benny Hill took the medium of television comedy whilst it was still in its infancy and helped shape its future in much the same way that Keaton and Chaplin influenced comedy on the big screen. Like all great clowns he always ensured that the only person who ended up as the butt of the joke was himself. His humour was at times a little crude, but was always delivered with a cheeky grin and a saucy twinkle in his eye. There was nothing malicious about it and at its most basic level it was no worse than school playground humour.

Benny Hill made the world laugh-and for that we should all be grateful.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus (2003) Sources of Reference: Life Is Funny (Articles published in weekly parts in TV MIRROR commencing 15th January 1955, written by Benny Hill. Star Turns written by Barry Took published in 1992 Benny Hill Merry Master of Mirth written by Robert Ross published in 1999. Radio Times Guide to TV Comedy written by Mark Lewisohn published in 1998 for Television Heaven.