Glen A Larson

Despite his remarkable career churning out hit after hit, Larson earned only three Emmy nominations; two for producing McCloud and one for outstanding drama for Quincy. He never won.

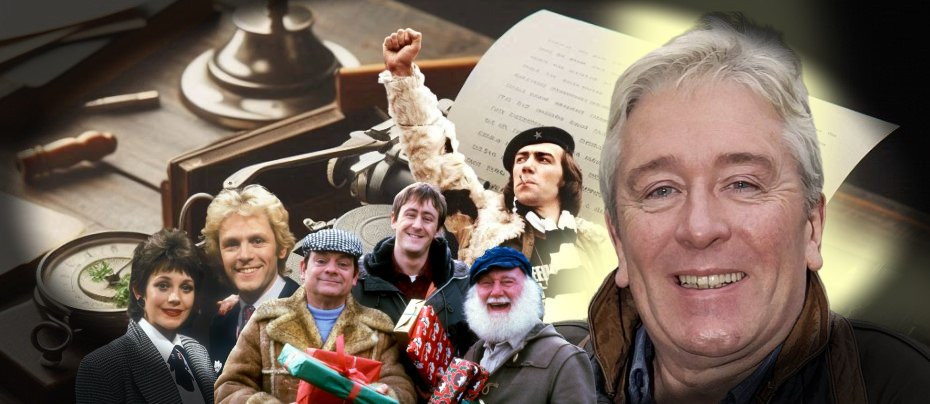

As the creator of such kitsch shows as Knight Rider, The Fall Guy, B.J. and the Bear, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century and Battlestar Galactica, Glen Larson had the knack of taking some of the most cliched material and turning it into TV gold. As one of the most prolific producers of Prime-Time television he had as many as five TV shows running at the same time on American TV networks, and those shows became world-wide hits. Years later he filed a lawsuit alleging that he was denied profit participation on shows earning hundreds of millions of dollars. But Larson was also something of a controversial figure, being branded by the Star Trek writer Harlan Ellison as “Glen Larceny”, for taking film concepts for his TV shows whilst others accused him of “never having an original idea of his own.”

In his autobiography, The Garner Files, James Garner stated that Larson stole a number of plots of The Rockford Files (the comedy detective series which Garner's production company co-produced), then used them for his own shows, simply changing the dialogue minimally and using different character names. When Larson visited the set of The Rockford Files, Garner described Larson as a “thief”, accused him of plagiarising storylines from the show and punched him so hard that he “flew across the kerb, into a motor home, and out the other side”. Garner said: “I only hit him with my left hand. If I’d hit with my right, I would have killed him.”

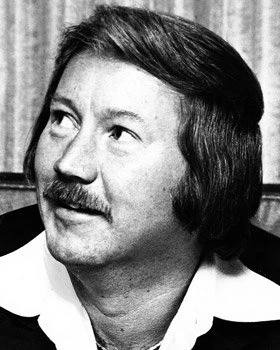

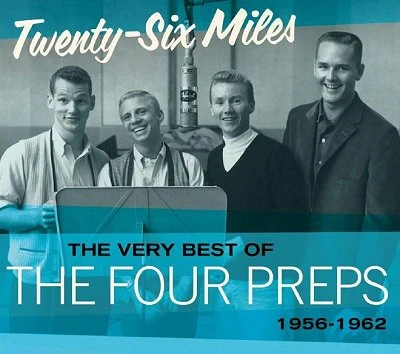

Glen Albert Larson was born on 3 January 1937 in Long Beach, California, the only child of a Swedish immigrant mother and a Swedish-American father. When he was young the family moved to Los Angeles. Larson began his career in the entertainment industry at the age of nineteen as a member of the pop group The Four Preps, who had met at Hollywood High School and were signed to a recording contract in 1956 by Capitol Records. In 1957, Larson and fellow group member Bruce Belland co-wrote the groups biggest hit, 26 Miles, which sold over a million copies. The duo also wrote Big Man, which was a big hit in the UK in 1958. Then in 1959 they appeared as themselves in the film Gidget, the light-hearted adventures of a free-spirited teenage all-American surfing girl.

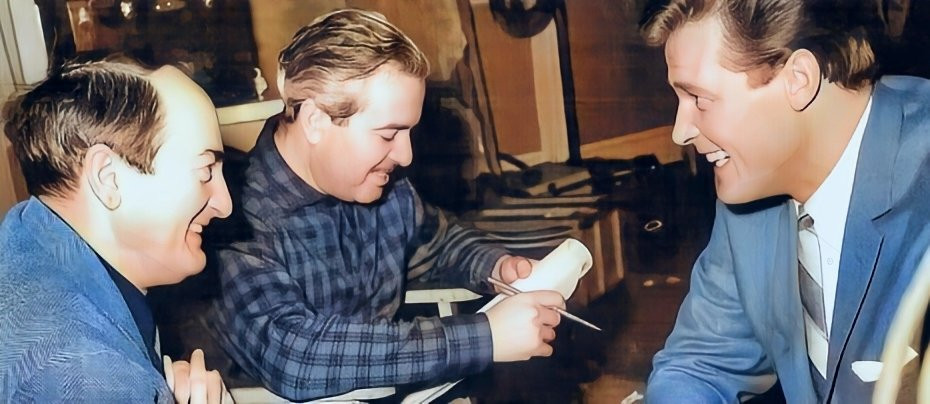

By the mid 1960s, and with a string of records behind them, some members of The Four Preps departed for pastures new. Among them was Glen Larson. He had begun working for Quinn Martin's television production company and in 1966 he received his first scriptwriting credit for an episode of The Fugitive, titled In a Plain Paper Wrapper. Apart from the star of the series, David Janssen, the episode also starred fifteen-year-old Kurt Russell.

Larson continued to hone his writing skills on popular TV productions such as the Robert Wagner vehicle It Takes a Thief (for which he became Associate Producer) and the popular Western series The Virginian. In 1970 he was Executive Producer on a Herman Miller creation titled McCloud, which starred Dennis Weaver (formerly Matt Dillon’s deputy in Gunsmoke) as a cowboy cop working in the big city. The series was based on the Clint Eastwood starring feature film Coogan’s Bluff, which Miller had co-written the screenplay for with Dean Riesner.

Then in 1971 Larson came up with his own creation - Alias Smith and Jones. The series, brought in as a mid-season replacement, was one of US television's last great flirtations with the Cowboy genre for many years, and, having taken the lead from McCloud, was itself inspired by the Hollywood blockbuster, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Larson would later admit that his series was “certainly in the genre of Butch Cassidy”, and described it as, “a New Wave Western”.

Larson was involved in the development for television of The Six Million Dollar Man, based on Martin Caidin's novel Cyborg, and was one of the programme's early Executive Producers. After ABC spurned the original pilot for it, Larson rewrote it and penned a pair of 90-minute telefilms. They convinced then-network executive Barry Diller to greenlight the series, which starred Lee Majors as a former astronaut supercharged with bionic implants. The opening and closing credits of those two feature-length episodes, Wine, Women & War and The Solid Gold Kidnapping, used a theme song written by Larson and sung by Dusty Springfield. However, when the weekly series began, the song was replaced by an instrumental theme by Oliver Nelson.

In 1976, Larson and Lou Shaw created a series about a brilliant but irascible Medical Examiner called Quincy. It was Larson’s most successful series up to that time and it won him an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Drama. But Larson and Quincy actor Jack Klugman didn’t get on and eventually Larson left the production in the hands of Donald P. Bellisario.

With his stock rapidly rising with Universal Television, Larson was able to secure a then-unprecedented $1 million per-episode budget for his next creation, Battlestar Galactica. He described it as “Wagon Train heading toward Earth” and claimed to have been working on versions of the drama for a decade, the earliest being called Adam’s Ark. But 20th Century Fox, who had made a killing at the box office the previous year with George Lucas’ Star Wars, were not convinced. They sued Universal for infringing Star Wars copyrights, but lost, and Battlestar Galactica continued but only until the end of the first season. “I was vested emotionally in Battlestar, I really loved the thematic things,” Larson would later state. “I don’t feel it really got its shot, and I can’t blame anyone else, I was at the centre of that. But circumstances weren’t in our favour to be able to make it cheaper or to insist we make two of three two-hour movies [instead of weekly 40-minute episodes] to get our sea legs.”

In the UK and some other countries, the Battlestar Galactica pilot was shown as a cinema release and did reasonably well at the box-office. Although initially a ratings success, the TV series soon faced stiff competition from rival networks. CBS moved its hit sitcom All in the Family back an hour in direct competition and Battlestar slipped in the ratings. In mid-April, ABC pulled the plug on it. It finished the 1978-79 season ranking at 34 out of 114 shows.

Much more successful for Larson was The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries. The series was based on the Hardy Boys, who first appeared in print in 1927, and the Nancy Drew juvenile novels, which first appeared in 1930, both of which told fictional tales of amateur sleuths. The books were the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, an American publisher and writer of children's fiction who founded his own company called the Stratemeyer Syndicate, and who created the characters of a sixteen-year-old sleuth, her lawyer father, and their housekeeper. His daughter, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams came up with plot ideas and hired ghost-writers to flesh them out.

The series, which ran from January 1977 to January 1979, was produced by Glen A. Larson from Universal Television for ABC. Future Dynasty star Pamela Sue Martin starred as Nancy, and the first season alternated with the Hardy Boys. And whilst the Hardy Boys met with success, the Nancy Drew episodes were met with mixed results. As well as their own self-contained stories there were also crossover plots, but for the third season, Nancy Drew was dropped altogether.

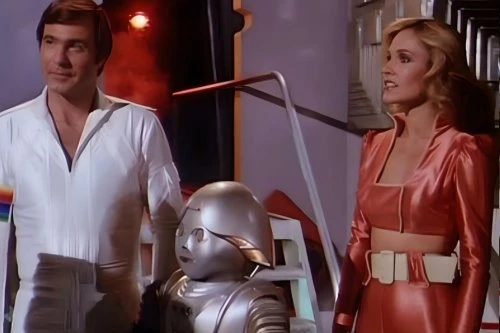

By the time Battlestar Galactica hit the screens, Larson was working on two more TV shows. Buck Rogers began life as a science fiction comic strip character in 1929 before appearing in books and multiple media such as radio (1932), and eventually a film series (1939) aimed at a young audience. It was a classic example of the Saturday weekly serial which always finished on a cliff-hanger, enticing youngsters to come back to the theatre the following week to see how their hero escaped from the latest life-threatening predicament. By 1978, Buck Rogers was regarded by American science fiction fans as something of a national institution. Universal were keen to not just have one Star Wars style TV show for television - but two. Buck Rogers had the advantage of being something that had been long built into the American psyche and Universal felt as though they were on reasonably safe ground.

Universal approached Glen Larson, with whom they had a production deal, to develop the concept for a modern audience. What he came up with was Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. The first two pilot episodes were released, once again, into theatres, but this time across America. Released in March 1979, it made $21 million at the box-office which was very encouraging. Enough for NBC to order a full series of 24 episodes to begin airing in September.

The production recycled many of the props, effects shots, and costumes from Battlestar Galactica, which was still in production at the time the pilot for Buck Rogers was being filmed - but it was still allocated $800,000 per episode. Although reasonably popular with viewers, the first season failed to receive much critical acclaim and opinions ranged from "the worst TV science fiction ever seen" to "the best comic-strip science fiction on at the moment". The star of the series, actor Gil Gerard, complained over NBC's handling of the series and the direction it was taking. He pushed for more serious storytelling and ended up clashing with the scriptwriters and producers. Gerard became more difficult to work with, and tensions on set were not helping the production. Nonetheless, a second season was ordered but this time it was delayed severely by an actors' strike. When it did return the format was changed more to Gerard's liking. But rating dropped alarmingly following season two's premiere and never recovered. NBC cancelled the series with just thirteen episodes recorded. Fans and critics remain, to this day, deeply divided on Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

The second series that Larson had in production by 1978 had taken its inspiration - or was directly copied from (depending on your point of view), the Clint Eastwood action comedy movie Every Which Way but Loose. The series, B.J. and the Bear, centred round Billy Joe McKay, who worked freelance as a trucker. His companion for his journeys was a chimpanzee named Bear. In the movie, Eastwood played Philo Beddoe, a trucker and bare-knuckle brawler roaming the American West in search of a lost love while accompanied by his brother/manager, Orville, and his pet orangutan, Clyde. But nobody sued.

Two years later, Larson struck TV gold once again. Donald P. Bellisario had been working on Battlestar Galactica, writing eleven of the episodes. In 1980, he approached Larson with an idea for a series about a well-to-do private investigator living in the luxury of Bel Air, the exclusive money drenched residential neighbourhood on the Westside of Los Angeles.

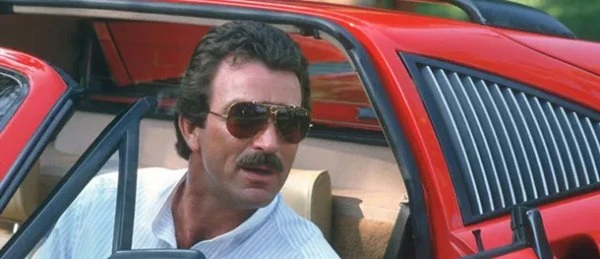

The potential of Bellisario's concept was immediately apparent to Larson who took the show to ABC – only for it to be turned down. Thankfully, Larson succeeded in interesting CBS executives in commissioning the series. This time his pitch paid off, but to get the go ahead, a number of key changes had to be made to the concept. The first of these changes was the relocation of the central setting to Hawaii. At the time, Hawaii Five-0 had reached the end of its televisual life and CBS wanted an immediate replacement series which could continue to use the extensive and expensive custom-built Hawaiian production facilities, which the network had had constructed in the mid-seventies for the out-going series.

The second key element was that of the selection of lead actor for the show. CBS had had Tom Selleck under contract for a TV series lead for some time, the actor having caught their eye when playing smug gumshoe Lance White in The Rockford Files. Selleck had shot a couple of pilots, but they had never been taken up as a series. With this new property, CBS executive's finally felt that they had the perfect vehicle for him. Selleck reportedly didn’t want the role as he was hoping to land the part of Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark. But CBS held him to his contract.

Magnum P.I. debuted on television in December 1980 and ran until May 1988. It consistently ranked in the top 20 U.S. television programmes in the Nielsen ratings during the first five years of its original run in the United States, finishing as high as number three for the 1982–83 season. In 1981, Larson and Bellisario received an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for Best Episode in a TV Series. Selleck won an Emmy in 1984 for his portrayal of the title character.

Larson later conceded that Magnum P.I. was influenced by his fondness for the 1960s CBS cop show Hawaiian Eye. “We got the star, it was a perfect fit. I had a house over there and a guy [like Selleck’s character] who lived in a guest house took care of it.” Larson based an unseen novelist character, the owner of Magnum’s home, on author Harold Robbins.

The next hit for Larson came after he’d finally cut his ties with Universal and moved to 20th Century Fox. The Fall Guy starred Lee Majors as Colt Seavers, a Hollywood stunt man who moonlights as a bounty hunter. Majors was also a producer and a director on the show, and even sang its theme song, the self-effacing "Unknown Stuntman." Spectacular stuntwork was the hallmark of this series which was Majors’ fifth successful prime-time series. Each episode kept viewers on the edge of their seats with its daring and death-defying stunts which usually involved a high-speed pursuit of the bail jumper. The Fall Guy ran to 112 episodes from 1981 to 1986, running for 5 seasons.

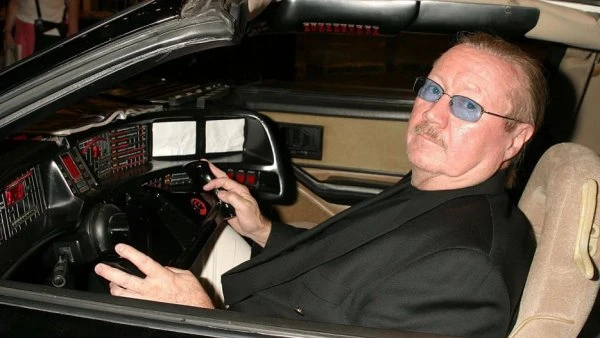

1982 was the last time that Larson launched a new series whilst he had multiple shows running on prime-time television. And it is still one of the best remembered. Knight Rider is another action-drama series but this time the stars are one man and his car.

Self-made billionaire Wilton Knight rescues police Detective Lieutenant Michael Arthur Long after a near fatal shot to the face, giving him a new identity (by plastic surgery) and a new name: Michael Knight. Reluctantly, Knight is put to work for a public justice organisation and given a multi-million-dollar asset in his fight against crime. Knight Industries Two Thousand (KITT) is a heavily modified, technologically advanced Pontiac Firebird Trans Am which is controlled by AI. In fact, the customised car used in the series cost a little less than the stated million - but it did cost the production company $100,000 to build. Larson said that the prototype for Knight Rider was The Lone Ranger: “If you think about him [Michael Knight] riding across the plains and going from one town to another to help law and order, then KITT becomes Tonto.”

Knight Rider was another series that the critics loved to loathe. Tom Shales, television critic for The Washington Post wrote of the series in 1982: "'Knight Rider' is all revved up but has no place to go, except, maybe, headlong into a large brick wall." But you can't keep a good car down and following 86 episodes, over four years, KITT's adventures were revved up again with the television films Knight Rider 2000, Knight Rider 2010 and the 18 episode revival series in 2008. Of course, times change and technology changes even faster. Today, many of the gadgets found on KITT come as standard on most cars.

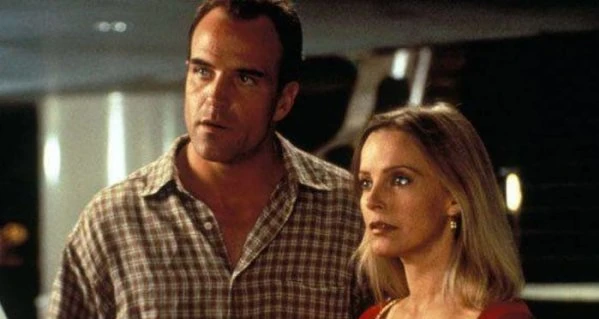

Larson wrote other teleplays in the 1980s and as we moved into the last decade of the old millennium there were some less successful series. In 1991 a Glen A. Larson and CBS Entertainment Production brought us P.S. I Luv U, a series about two people who had been working together for the NYPD, who – due to a failed 'sting' operation, must go into witness protection. The series was cancelled midway through its first season. In 1994, Larson created One West Waikiki, another crime drama starring former Charlie’s Angel Cheryl Ladd. This show fared a little better, surviving for two seasons although that only amounted to 19 episodes. Unusually, the series debuted in the summer from August to September, and then in first-run syndication for its second season from October 1995 until May 1996. The New York Times reported that the show's producers sought a summer slot in order to raise money for filming more episodes because they had already sold the idea of the programme to international broadcasters.

Larson's last hurrah in 1997 was more in keeping with his previous fantasy offerings. Night Man was based on the comic created by Steve Englehart about a jazz musician who gains super powers after he is struck by lightning. The strike allows him to telepathically recognize evil but robs him of the ability to sleep. Night Man has no other superhuman powers of his own, he owns a special blue-caped bulletproof black bodysuit that gives him several abilities, including flight, holographic invisibility, advanced sight functions through his mask and the ability to fire a laser beam. The series was a co-production between Glen Larson Entertainment Network, Inc, Village Roadshow Pictures (the American subsidiary of an Australian media company) and Alliance Atlantis (a Canadian media company). There were 44 episodes over 2 seasons. In 1999 it was nominated for five Leo Awards (the awards program for the British Columbia film and television industry), winning one for Graeme Coleman for Best Musical Score in a Dramatic Series.

Despite his remarkable career churning out hit after hit, Larson earned only three Emmy nominations, two for producing McCloud and one for outstanding drama for Quincy. He never won. He did win a Grammy in 1979 for co-writing the score for Battlestar Galactica and two Edgar Awards (the Mystery Writers of America (aka the Edgar Allan Poe Awards) for both McCloud and Magnum (the latter of which he shared with Donald P. Bellisario) and was also given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his contributions to the television industry.

In 2003, three production companies, BSkyB, David Eick Productions and NBC Universal Television produced a far more successful sequel to Battlestar Galactica which ran for 74 episodes over five years, and in 2009 there was a spin-off series: Caprica. Magnum P.I. was revived in 2018 and stars Jay Hernandez as the eponymous hero. Up to 2023 there have been 86 episodes. A movie of The Fall Guy starring Ryan Gosling and Emily Blunt is expected in 2024.

Glen Larson passed away on 14 November 2014 at the age of 77. He had been suffering from oesophageal cancer. He left behind him a catalogue of television shows that is unrivalled by any other showrunner. He didn't always stick with the shows he created. “I tried to stay with things until I thought they were on their feet, and they learned to walk and talk.” he said. Combined, Quincy, Magnum, Knight Rider and The Fall Guy accounted for 513 hours of television and 21 combined seasons from 1976-88. It wasn’t always plain sailing. “If you believe in something, you must will it through, because everything gets in the way. Everyone tries to steer the ship off course,” and the critics were often harsh and the accusations of piracy were rife throughout his lifetime. “Television networks are a lot like automobile manufacturers, or anyone else who’s in commerce,” Larson once explained. “If something out there catches on with the public … I guess you can call it ‘market research’”.

“Larson is undeniably a controversial figure in TV history because of his reputation for producing video facsimiles of popular films, but scholars, fans and critics should also consider that ‘similarity’ is the name of the game in the fast world of TV productions,” John Kenneth Muir wrote in his 2005 book, An Analytical Guide to Television’s Battlestar Galactica. “Shows are frequently purchased, produced and promoted by networks not for their differences from popular productions, but because of their similarities.”

His shows, Larson said, “were enjoyable. They had a pretty decent dose of humour. All struck a chord in the mainstream. What we weren’t going to do was win a shelf full of Emmys. We got plenty of nominations for things, but ours were not the kind of shows that were doing anything more than reaching a core audience. I would like to think we brought a lot of entertainment into the living room.”

Published on June 2nd, 2023. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.