Verity Lambert

Described as a "total one-off - a magnificently, madly, inspirationally talented drama producer," Verity Lambert made the television drama genre utterly her own. Her career spanned the eras, from the first episode of Doctor Who through to Jonathan Creek and beyond, her shows were enduring and her talent unique

Most women entering television in the early 1960s were channelled into a career path that was assumed to be more suited to feminine capabilities. There had, previous to that, been some exceptions but they were few and far between. In the male dominated medium it was assumed that woman were only suited for roles that constantly fell into the same clichéd categories - fashion, lifestyle, the arts, or children's programmes. But comedy and serious drama were still very much the bastion of men.

Championed by an independent television producer from Canada, Verity Lambert finally broke through that wall of naïveté, although she still needed a single-minded determination and indomitable spirit to do so. Luckily, she had both in abundance.

Verity Lambert was born in London on 27 November 1935, the daughter of a Jewish accountant, and was educated at Roedean School in East Sussex. A bright student, Verity left school at sixteen years of age with six O' Levels before pursuing a six-month language course in Paris. In 1956, she entered the television industry as a secretary at Granada Television's press office but was dismissed after six months.

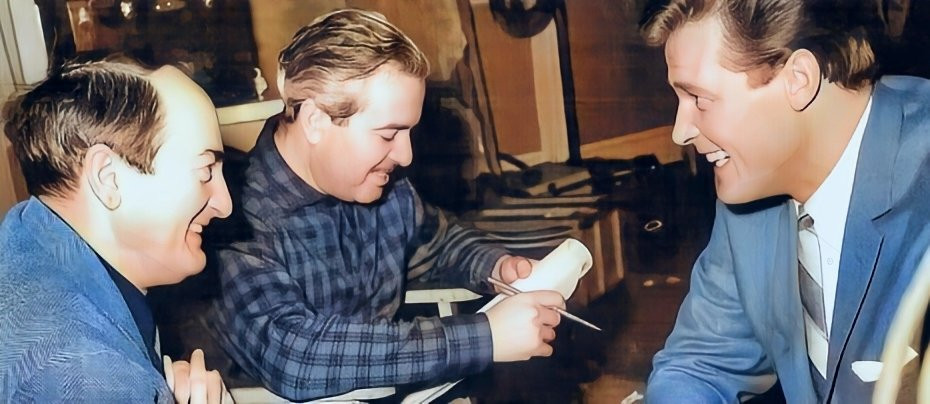

Undeterred, Verity took a job as a shorthand typist at ABC television where she clearly made a much better impression because she was promoted to secretary to the company's head of Drama, Sydney Newman. The Canadian producer clearly saw something in Verity that he liked because she soon found herself being moved from administration to production and by 1958 she was working as a Production Assistant on the anthology series Armchair Theatre.

It was whilst working on an AT production on 28 November 1958 that she was thrown into the deep end of a television crisis. The actor Gareth Jones died during a live broadcast and Verity had to hurriedly take charge of camera directions whilst the director of the play, Underground, worked with the other actors to hide the tragedy from the television audience and redirect them by redistributing the deceased actor's lines.

In 1961, Verity left ABC to work in New York as personal assistant to American television producer David Susskind. Returning to England, she went back to ABC hoping that the opportunity would arise for her to direct. However, ABC didn't show any inclination in helping her to achieve her ambitions and she began making plans to abandon television as a career. By now, Sydney Newman had left ABC to take up the role of Head of Drama at the BBC. Newman was making plans for a new science fiction series called Doctor Who and had approached a few producers to take up the series but they had turned him down. Remembering how impressed he was with Verity; her work ethic, her drive and her professionalism at ABC, he offered her a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Verity not only became the BBC's only female producer, she also became the youngest.

"People were astonished that a woman, and a young woman at that, would be given that job.” She later revealed. “Some people were quite outspoken about it. Other people registered shock and surprise and then tried to rearrange their face into something resembling a pleasant smile. I was only 27 and I was doing a job that a lot of men wanted and couldn't get. But in a way it didn't really bother me, perhaps because I had the supreme confidence of ignorance and youth." 1

William Russell, who played Ian Chesterton, was aware of the pressure Verity was under and had the impression that no one at the BBC wanted Doctor Who to be a success. "Children's television at the BBC had been a very special enclave and they produced some very remarkable work. Sydney Newman arrived and made Doctor Who and it stood rather uncomfortably between two stools. Not really children, not really drama. Verity was always having problems with little jealousies, but she was an enormous support, terrific all the time.”2 Verity later recalled that "aside from the Children's Department, the Design Department in the early weeks were enraged by us - not the designers themselves, but the people who ran it were extremely unhelpful."

"It was a huge jump from production assistant to a producer in one fell swoop. People were astonished when I got that job and it was the most wonderful thing to do, because it was so imaginative. It didn't have a tried and tested formula; we were making our own mistakes as we went on and we were making our own rules as we went on." 3

Before she had arrived at the BBC some scripts had been commissioned for the first story, but Verity didn’t think much of the first Doctor Who adventure which was set in prehistoric times and featured cavemen and cavewomen. "I thought it was a bizarre and mad thing to start a series off with. There is a very fine line before men in bare legs and lots of fur become extremely funny. I think it's all credit to Waris Hussein who directed that first series that he managed to hit the line of it being interesting."

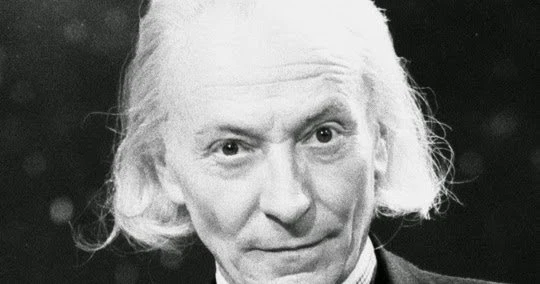

It was Verity’s decision to cast William Hartnell as The Doctor. "For me he's always been the most like I saw the Doctor. He had that kindness and was vulnerable, but he could get angry and quite frightening as well. He just combined all those things in absolutely the best way."

Initially, Verity was told that the series had to finish after thirteen weeks. "I was called in and told the show was too expensive and stretching facilities far too much for a children's programme." But Verity fought her corner well. She explained that taking the show off was impractical as the four part caveman story was already in the can, the seven part Dalek story was in production and they had already committed to the seven part Marco Polo adventure. The BBC accepted her plea and decided to return at a slightly later date to make a final decision on the show's future. But by the time that came round, Doctor Who, or rather the Daleks, had taken the country by storm.

"David Whitaker [had] commissioned [the] Dalek series and when it came in both he and I thought it was absolutely terrific." Said Verity. "But we were the only people who did. Donald Wilson, who was our head of department, absolutely hated it and indeed had we had anything else to put in its place it wouldn't go out because he said, 'this is terrible, you can't do this'. David and I were rather thunderstruck by this because we both thought it was good. Anyway, we put it out and it was an absolute instant thing. It catapulted the show. And Donald Wilson, to give him his credit, called me in and said 'you clearly know more about this that I do, I won't bother to interfere in the future.' Up to that point there had been a real question mark as to whether we would go [much further]."

Despite the success of the Dalek story, Verity always preferred the historical ones. "I think we were always much more successful with the historical ones because we had some facts which we could fall back on. The future ones were more difficult and although I was made to read New Scientist every week, I couldn't understand most of it, so I don't think we succeeded in that area. But I think we succeeded in being entertaining. I tried to make a programme for adults, but there wasn't adult things like sex or violence - it was simply adventures." 3

However, Verity was having to defend the show again following the two-part Inside the Spaceship story. There was one scene where the Doctor's grandaughter, Susan, menaces fellow travellers Ian and Barbara with a pair of pointed scissors that many parents and critics thought was wholly inappropriate - and they were very vocal about it. "The full weight of the Children's department came down on us, and in retrospect, I realised I had made a mistake in letting it go through. It might have been dubious to have had any of the characters holding the scissors, but because it was a child (Susan's age was 15), that made it an even bigger mistake." Verity was told to write an apology to the Children's Department which she duly did. "I was mainly concerned with making something that children could enjoy and not feel that this was a special programme for them, avoiding all the twee and awful things people normally put into children's programmes." 4

Thankfully, after the scissors incident, there was no more controversy.

The next major upheaval for the show was the departure of its first regular cast member. Carole Ann Ford had become disillusioned with her role, which did not develop as she was told it would when first cast.

It wasn't long after that that Verity decided her time was also up on the series. "I had done sixty or seventy programmes and I felt someone else should come in and bring something else to it. I didn't want it to go stale and I didn't want to go stale, either."

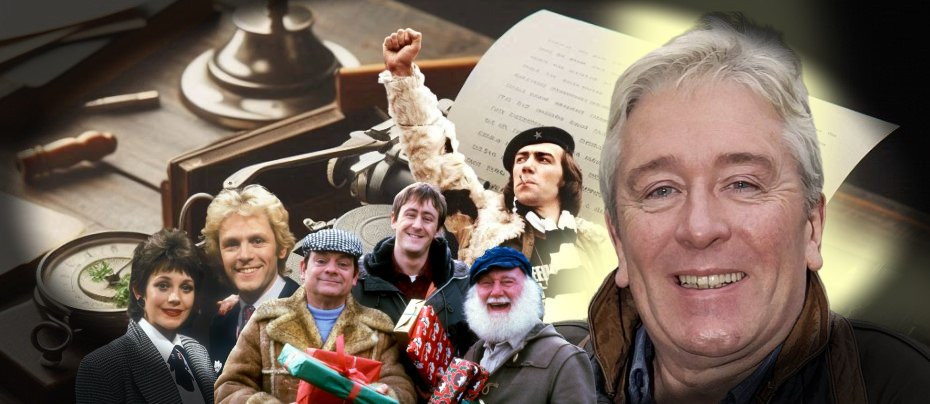

After leaving Doctor Who, Sidney Newman assigned Verity to another of his shows which also developed something of a cult status. However, Adam Adamant Lives! was not quite ready to go into production yet so she began working on the initial episodes of another new series; The Newcomers, which debuted in October 1965. It was the following June before Adamant hit the screens. Verity likened Adam Adamant to Mark Twain's A Yankee at King Arthur's Court, a story of two different branches of society looking at each other. "I suppose that's what I tried to attain in Adam Adamant. I don't think we ever achieved it because Mark Twain was a rather good writer, but that's what fascinated me - the whole idea of life in Britain in the sixties being seen through Victorian eyes so attitudes could be pointed out and the ones that were good could be shown to be so and the ones that were silly could be made fun of."

After two seasons of Adam Adamant Lives! Verity produced Detective, a series that had originally aired for one season in 1964 but was being revived in 1968. But by that time, Verity was beginning to feel somewhat underused by the BBC and despite being given the production role on all twenty-six episodes of W. Somerset Maughan in 1969/70, she decided that her future lay elsewhere.

In 1970, Verity moved to London Weekend Television on the ITV Network and produced Budgie, a series about a chirpy Cockney wide-boy and petty thief who was always destined to failure.

After 26 episodes of Budgie she moved on to Between the Wars, six plays specially adapted from English short stories written between the Twenties and Thirties. In 1974, she briefly returned to the BBC but in a freelance capacity to produce Shoulder to Shoulder, an historical drama series depicting the women's suffragette movement in Britain. That same year, Verity became Head of Drama at Thames Television.

During her time at Thames, Verity commissioned a number of series which included Rock Follies. Howard Schuman, the writer of Rock Follies, later praised the bravery of Verity's commissioning. "Verity Lambert had just arrived as head of drama at Thames TV and she went for broke," he told The Observer newspaper in 2002. "She commissioned a serial, Jennie: Lady Randolph Churchill, for safety, but also Bill Brand, one of the edgiest political dramas ever, and us ... Before we had even finished making the first series, Verity commissioned the second." She was responsible for the decision to dramatise Quentin Crisp's memoirs as The Naked Civil Servant (which at that time was acclaimed the highlight of serious television drama), and Edward and Mrs Simpson, and snapped up the rights to Rumpole of the Bailey from under the nose of the BBC who had made the original televised play but were dithering on commissioning a series. In 1976, she was also made responsible for overseeing the work of Euston Films, Thames' subsidiary film production company.

Verity started off at Euston Films by revamping the established Special Branch series and Van Der Valk - making both series on film - and green-lit Minder, Reilly Ace of Spies, The Flame Trees of Thika, Fox and Quatermass, all of which she was Executive Producer for. However, she was unhappy with the latter. "I thought it was a wonderful idea to have [Professor Quatermass] as an old man. I just don't know whether we pulled it off. In a curious way it was quite an old fashioned idea - the cult of hippies - and I don't think it was quite modern enough."

Her association with Thames and Euston Films continued into the 1980s. In 1982, she re-joined the staff of parent company Thames Television as director of drama and was given a seat on the company's board. In November 1982 she left Thames but remained as chief executive at Euston until leaving in November of the following year to take up her first post in the film industry, as director of production for Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment. However, this was the least successful period of her professional life. "Unfortunately, the person who hired me left, and the person who came in didn't want to produce films and didn't want me. While I managed to make some films I was proud of — Dennis Potter's Dreamchild, and Clockwise with John Cleese — it was terribly tough and not a very happy experience."

Frustrated by her time at Thorn EMI, Verity set up her own production company, Cinema Verity, in 1983 which had its first success with the sitcom May to December. The company also produced another successful BBC1 sitcom, So Haunt Me, which ran from 1992 to 1994 and produced filmed series such as Widows, Sleepers and G.B.H. However, the latter's writer, Alan Bleasedale, later admitted that he "wanted to kill Lambert" after she insisted on cutting large portions of his draft script. Only later did he admit that she was right about the majority of the cut material.

After so many years of producing successful television programmes it was perhaps inevitable that a failure was bound to happen. That failure did come with the much-derided Eldorado, a soap opera about ex-pats living in fictional Spanish resort of Los Barcos. "What was foolish about Eldorado, and I will take full responsibility for it, was being an independent producer, when somebody says 'we want it by this time', you don't always take the sensible decision. It was put on the air too early. We had to iron out the teething troubles on air, which was ridiculous. We had three or four months of not good enough stuff. If we had more time that stuff would never have got on air." 1 Reviewers were particularly scathing about Eldorado. Rupert Smith's comments in The Guardian in 2002 summed up many people's opinion. "A £10 million farce that left the BBC with egg all over its entire body and put an awful lot of Equity members back on the dole ... it will always be remembered as the most expensive flop of all time."

Attempting to bounce back from the failure of Eldorado, Verity tried to acquire the rights to produce Doctor Who independently for the BBC, but by that time the Corporation was in negotiations with producer Philip Segal in the USA. The series would have been produced by Cinema Verity, but it didn't happen. Instead, working as a freelancer outside her own company, she produced the BBC comedy-drama Jonathan Creek.

In 2002, Verity was appointed an OBE in the New Year's Honours List and received BAFTA's Alan Clarke Award for Outstanding Contribution to Television. She was also due to be awarded a lifetime achievement award at the Women in Film and Television Awards in December 2007, but on 22 November she passed away, aged seventy-one years, having succumbed to cancer five days before her birthday.

In 1999, Verity summed up her feelings about modern television in a way that some critics may well see a parallel with today. "I think there's far too much on television which is far too much like each other. I know people love detective stories, but it seems like there's an unending line of detective stories. I'm not saying that those things don't have a place, they do, and when they're good they're very good, but it does seem like people aren't encouraged to be original. I think people commissioning now are scared to have anything too original, they basically want something that is tried and true and is the same as something else. And that's basically what you get." 3

Verity Lambert left a lasting legacy that still resonates. Doctor Who notwithstanding, she produced some of the most innovative, thought provoking, provocative and entertaining television that Britain has produced. And even more importantly, she entered a world that was almost exclusively male dominated and refused to be intimidated by it, constantly breaking down barriers and leading the way for some of the most talented female producers, directors and writers to excel on the world stage.

Jane Tranter, the British television executive who very much followed in that legacy's footsteps, paid tribute to Verity Lambert when she said: "She made the television drama genre utterly her own. She was deaf to the notion of compromise and there wasn't an actor, writer, director or television executive she worked with who didn't regard her with admiration, respect and awe."

1 TV Zone 1995

2 TV Zone Special #31 December 1998

3 Talking in 1999

4 Doctor Who The Early Years by Jeremy Bentham

Published on April 6th, 2023. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.