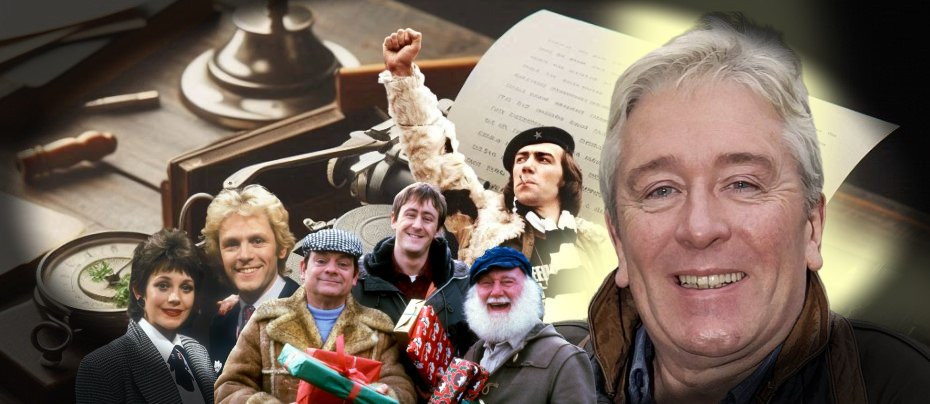

Willie Rushton

A Life of Satire, Wit, and Irreverence

William George Rushton, known to most simply as Willie, was a comic force of nature whose work as a cartoonist, actor, writer, and satirist left an indelible mark on post-war British culture. As one of the key architects of the satire boom of the early 1960s, Rushton was part of a generation that used humour as a weapon against pomposity, power, and the political status quo.

Born on 18 August 1937, at 3 Wilbraham Place in Chelsea, London, Rushton came from a respectable and bookish background. His father was a publisher, and his grandfather, a Wigan lawyer, had been right-hand man to industrial magnate Lord Leverhulme. Despite his pedigree, Rushton never displayed much enthusiasm for formal education. His real training came not from textbooks, but from his time at Shrewsbury School, where he met kindred spirits Richard Ingrams, Christopher Booker, and Paul Foot - future fellow agitators in the world of satire.

The boys' rebellious humour found its first outlet in The Wallopian, a cheeky parody of the school’s official magazine The Salopian. While others wrote the pieces, it was Rushton’s cartoons that gave the publication its unique personality. Although a cartoon of a giraffe in a bar saying "The high balls are on me" was not met with approval by everyone in the university administrative quarters.

At Shrewsbury, Rushton also found the stage. His comic timing was evident even then, when he played the elderly Lord Loam in The Admirable Crichton.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Rushton didn’t attend university. Instead, he joined the Army for National Service, an experience he later described as “one of the funniest institutions on Earth.” He saw in the military a microcosm of Britain’s class system, and it sharpened both his political scepticism and his comic eye.

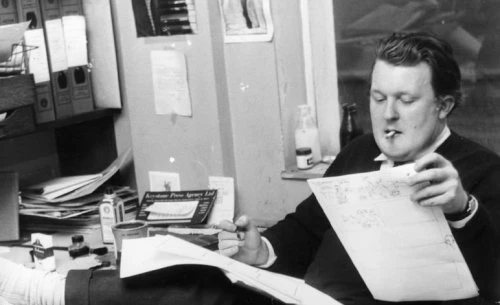

Returning to civilian life, Rushton worked briefly as a clerk in a solicitor’s office. But his passion for drawing never left him. He continued to send cartoons to Punch, though none were accepted. A brush with death, being knocked over by a bus, led him to quit the job. "I decided not to waste another day," he recalled. And with that, his real life began.

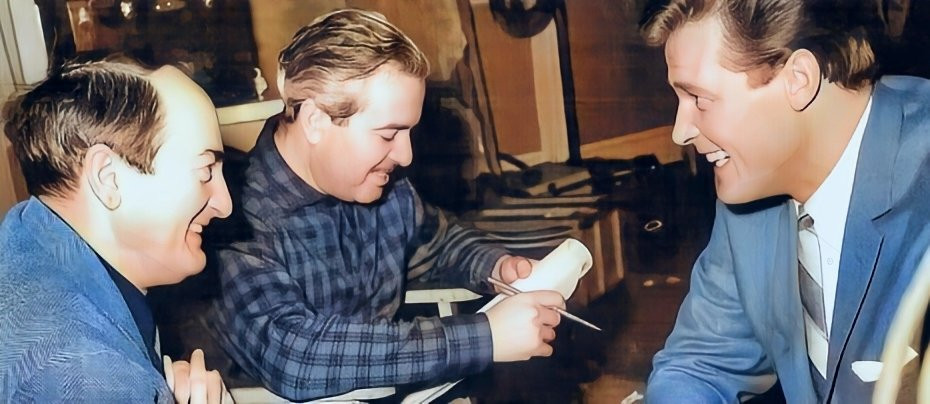

Over pints in a Chelsea pub with Richard Ingrams and Christopher Booker, the idea for a satirical magazine was born. In 1961, Private Eye launched, with Rushton's irreverent and instantly recognisable cartoons giving the magazine its visual identity. The Eye quickly became a phenomenon, skewering the pompous and powerful with a blend of wit, mockery, and unflinching insight.

That same year, Rushton made his professional stage debut in Spike Milligan's The Bed-Sitting Room, a surreal comedy about nuclear war. It proved an ideal launching pad for what would become his most iconic venture.

In 1962, the BBC unveiled That Was the Week That Was (aka TW3), a revolutionary programme that broke every rule of polite broadcasting. Hosted by the then-unknown David Frost, the show featured a cast of sharp minds, including Rushton, Lance Percival, Bernard Levin, John Cleese, Millicent Martin, Roy Kinnear, Eleanor Bron, and John Wells.

Rushton’s impersonation of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was one of the show’s highlights, an audacious jab at the Conservative establishment that shocked older viewers and thrilled younger ones. His lampooning of establishment figures was emblematic of a generational shift: these were not simply comedians; they were insurgents, furious with the stale politics of post-war Britain.

Though TW3 was a runaway success, with audiences of up to 13 million, it was not universally loved. One week alone drew 443 angry phone calls. Rushton’s appearance, often scruffy and dishevelled, was a target of criticism, though it only added to his image as an anti-establishment rebel.

The sequel to TW3, Not So Much a Programme, More a Way of Life, failed to recapture the magic. Rushton left early, disillusioned by its lack of bite. Around the same time, in a stunt encouraged by his Private Eye peers, he stood in the 1963 Kinross by-election against Alec Douglas-Home, garnering just 45 votes. It was a theatrical gesture more than a political one; Rushton, though a Labour supporter, admitted he wasn’t “very good with organisations.”

In cinema, he popped up in comic films like Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965) and Monte Carlo or Bust (1969), often playing bumbling Englishmen or eccentrics.

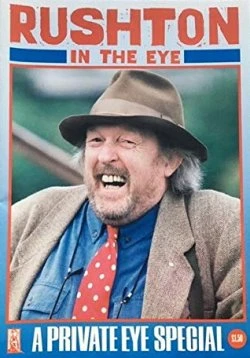

Rushton returned to the stage from time to time, appearing in Gulliver's Travels at the Mermaid Theatre and and throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he continued to appear on television in Not Only... But Also with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, and in the campy historical sitcom Up Pompeii! with Frankie Howerd. He also took on a more serious role in the BBC drama Colditz playing Major Trumpington, complete with red beard, kilt, and woolly hat. Rushton's own television series, Rushton's Illustrated (1980), made little impact, and much of his later TV work consisted of guest appearances on quiz and game shows, including Celebrity Squares.

Rushton’s wit found its most enduring home on the radio. He was a regular panellist on I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue, Radio 4’s beloved “antidote to panel games,” from its inception in 1972 through 27 series. His off-the-cuff humour and absurd inventions endeared him to listeners for decades.

He also voiced the gloriously anarchic schoolboy Nigel Molesworth in the BBC radio series Molesworth (1987), and made memorable appearances on children’s favourite Jackanory, captivating a younger generation with his storytelling.

In later years, he toured the stage with fellow veteran comic Barry Cryer in Two Old Farts in the Night, proving that age had not dulled his comic instincts.

Throughout his life, Rushton remained first and foremost a cartoonist. His drawings appeared in Private Eye, The Daily Telegraph, Literary Review, and for many years, The Independent Magazine. His work was also exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, a recognition of his influence and talent.

He authored numerous humorous books, including William Rushton's Dirty Book (1964), The Filth Amendment (1981), Willie Rushton's Great Moments of History (1985), and spoof titles like The Day of the Grocer (1971) and Spy Thatcher (1987).

Willie Rushton died of a heart attack on 11 December 1996 at the age of just 59 years. Eerily, during an episode of I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue, which aired on 26 July 1986, Chairman Humphrey Lyttelton asked the panellists to "gaze into their crystal balls" and make predictions for 1996. Rushton said, "I'm sorry you introduced this round, because I just spotted a memorial service for myself in Westminster Abbey in January".

Rushton’s legacy remains one of fearless, irreverent humour. He helped reshape the boundaries of British comedy and political satire, never afraid to poke fun at those in power, and always ready with a cartoon or quip that laid bare the absurdity of the times.

Though he claimed to hide behind humour; "My basic defence is Blitz humour," he once said, his contribution was deeply serious. He gave a generation permission to laugh at authority, and in doing so, he changed the face of British comedy forever.

Published on September 5th, 2025. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.