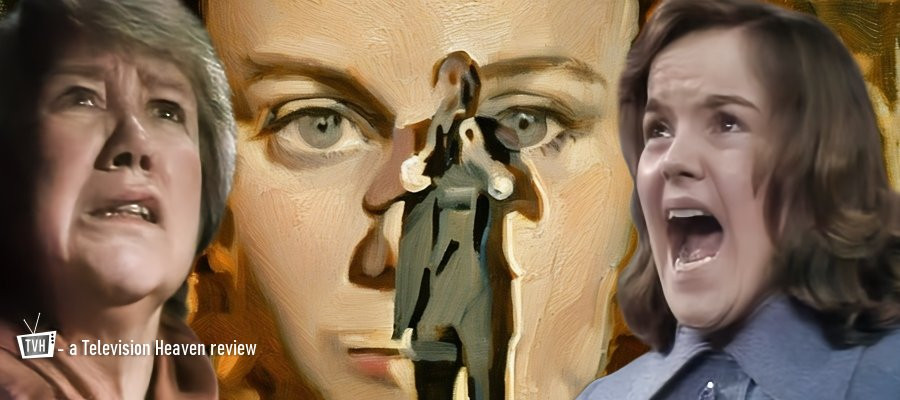

An Englishman's Castle

1978 - United KingdomAn Englishman’s Castle remains one of the most unsettling “what if?” dramas ever produced by British television, not because it indulges in spectacle, but because it refuses to. Philip Mackie’s three-part Play of the Week imagines a Britain that lost the Second World War and quietly learned to live with the consequences. The horror lies not in jackboots and banners, but in the banality of compliance.

Set in a 1970s United Kingdom functioning smoothly under German oversight, the series explores a society where order has replaced freedom and survival has trumped resistance. Nazi rule is largely invisible: there are few Germans on the streets, no overt displays of force. Control is instead exercised through bureaucracy, collaborators, and a soft-spoken English police force that politely escorts dissidents to places never shown on screen. It is an authoritarianism rendered chilling precisely because it feels plausible.

At the centre is Peter Ingram, played by Kenneth More in what would be his final television role and arguably one of his finest. Ingram is a successful, comfortable television writer-producer responsible for a hugely popular soap opera—also titled An Englishman’s Castle—which dramatizes domestic life during the imagined German invasion of 1940. Ostensibly nostalgic entertainment, the programme is in fact a carefully calibrated tool of state messaging, reinforcing acceptance of occupation and the idea that endurance matters more than defiance. Ingram initially embraces this role, valuing ratings, status, and material ease over uncomfortable truths.

Mackie’s brilliance lies in using television itself as both subject and weapon. Ingram’s soap opera becomes a mirror of the wider society: reassuring, emotionally manipulative, and quietly ideological. As Ingram begins to grasp the extent of what he is complicit in—through censorship demands, the erasure of Jewish existence, and his discovery that his lover Jill is both Jewish and part of an underground resistance—his moral detachment erodes. The regime’s insistence on forgetting, rather than denying, the extermination of the Jews is particularly chilling, suggesting a culture built on deliberate amnesia.

Kenneth More’s casting is inspired. Long associated with patriotic wartime heroism, he brings enormous resonance to a character who once fought bravely, then chose accommodation over continued struggle. His Peter Ingram is not a villain but a tired, recognisably human figure, shaped by loss, exhaustion, and the seductive comfort of normality. The performance gains power precisely because it subverts More’s established screen persona, turning the familiar “Come on, chaps” hero into a man who must relearn courage late in life.

The series builds inexorably toward its devastating final act, when Ingram agrees to let his programme carry the coded signal for a nationwide uprising. His ultimate decision—to speak the words himself, live on air—reclaims authorship, voice, and responsibility in a world designed to strip all three away. The closing moments, as the sounds of rebellion drift through the windows and Ingram faces the inevitable knock at the door, are stark, unresolved, and unforgettable.

Produced by Innes Lloyd and directed with restraint and intelligence by Paul Ciappessoni, An Englishman’s Castle is bolstered by strong supporting performances from Isla Blair, Anthony Bate, Nigel Havers, and others. Rarely repeated but released on BBC home video, it is haunting, ahead of its time and an eerily relevant drama. It endures because it asks an uncomfortable question: not how tyranny arrives, but how easily ordinary people learn to live with it. In doing so, it stands as both a warning and a quiet tribute to the fragile, hard-won nature of freedom.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 31st, 2026. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.