The Mind Beyond

1974 - United KingdomWhen the BBC launched The Mind Beyond under the Playhouse banner in the mid-1970s, it was stepping into uncertain territory. Anthology drama had long been a laboratory for ideas, but this six-part series, produced by Irene Shubik, ventured into a realm that was as culturally charged as it was dramatically elusive: extrasensory perception.

Shubik was no detached commissioner chasing a ratings hook. Interviewed in Radio Times, she spoke candidly of her own belief in telepathy between people who are close, and of her conviction that individuals can sense disasters before they occur. The catalyst was personal. While holidaying in Israel in Autumn 1973—having just completed work on Wessex Tales—she was suddenly overcome by dread. Hours later, as the Yom Kippur War broke out around her, the intuition seemed chillingly vindicated. For Shubik, experiences like this suggested that ESP was not just fit for speculation, but ripe for drama.

One of the series’ strengths lies in its refusal to preach. Shubik assembled playwrights with sharply differing views, and the resulting plays argue with one another as much as they explore the unknown. The result was uneven, provocative, and frequently fascinating television.

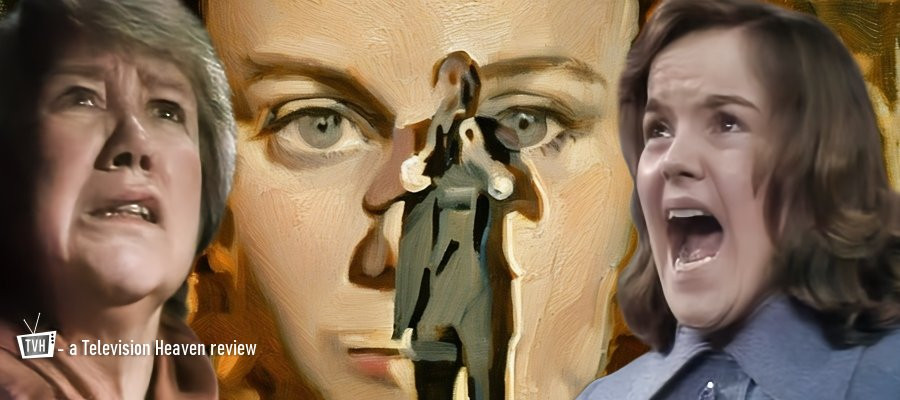

David Halliwell, a declared sceptic, contributed Meriel, The Ghost Girl a drama about the apparent materialisation of a dead girl. Halliwell doubts that anything so tangible as a ghost could exist, suggesting instead that hallucination—psychological or even sexual in origin—accounts for many “supernatural” claims. His contribution grounds the series in rational doubt, reminding viewers that the mind is capable of manufacturing its own phantoms.

Featuring an eclectic cast—including rare acting work from Janet Street-Porter alongside Donald Pleasence and John Bluthal (The Vicar of Dibley)—the episode offered three competing interpretations of the event. Was Meriel real? Fraudulent? A collective delusion?

Other episodes widen the thematic net. Brian Hayles’s Double Echo starring Jeremy Kemp (Peter the Great) and Anthony Bate (Grady), centres on a child thought to be autistic, probing whether extraordinary cognitive gifts might sit alongside—or even overlap with—forms of heightened perception. Hayles avoids crude claims that autistic children possess psychic powers, yet he is intrigued by moments of unexplained harmony between them. His speculative idea—that inserting a “key figure” might unlock communal communication—gives the play a faintly science-fiction edge, while remaining rooted in social reality.

Communication, too, drives The Daedalus Equations by Bruce Stewart, starring Megs Jenkins (Weavers Green), George Coulouris (Mussolini: The Untold Story) and Peter Sallis (Last of the Summer Wine). Inspired by Rosemary Brown, the London housewife who claimed to transcribe new compositions from long-dead masters like Mozart and Chopin, Stewart imagines a more consequential possibility: what if the spirit world transmitted scientific equations instead of sonatas? His argument is pragmatic rather than mystical. If ESP yielded verifiable breakthroughs, governments would waste no time in harnessing it. As he wryly notes, the trouble is that most mediumistic output is trivial—hardly the stuff of revolutions.

William Trevor’s contribution, The Love of a Good Woman, shifted toward emotional subtlety. Starring William Lucas (Dumb Martian) and Anna Massey (Season’s Greetings), the play intertwines love, remorse, and the faint possibility of reincarnation. Rather than spectacle, it offers a quiet, melancholic chill. Trevor’s script treats the supernatural as an extension of human longing—less an intrusion from beyond than a reverberation of unresolved guilt. It stands among the anthology’s more polished and affecting pieces.

Stones starring Judy Parfitt (Call the Midwife) and Richard Pasco (Drummonds) embraced Britain’s 1970s fascination with megalithic mysticism. Echoing the atmosphere later popularised by Children of the Stones and resonant with the folk-horror currents of Quatermass, it stands as the anthology’s most traditional entry. A Story of Stonehenge and its attendant myths and curses, in which three children carry out strange ritual connected with Stone -age cultures. Ancient landscapes, buried energies, and ancestral memory dominate—a reminder that British supernatural drama of the period often found its uncanny in the soil itself.

The final episode, The Man With the Power by Evan Jones, starring Johnny Briggs (Coronation Street), Geoffrey Bayldon (Catweazle) and Willie Jonah (Doctor Who) stands out as the most openly provocative of the series. Sympathetic to the idea of ESP and drawing connections between psychic phenomena and religious mysticism, Jones constructs a layered allegory centred on second sight, identity, and the divine. A widely noted same-sex interracial kiss between a devil-like figure and a Black protagonist—who may or may not be a Christ figure—sparked discussion, though in execution it feels less shocking than intellectually audacious.

Ambitious and laden with symbolism, the play occasionally buckles beneath its own metaphysical ambitions. Even so, its bold interweaving of theology, race, and psychic experience secures its place as one of the anthology’s most adventurous and uncompromising instalments.

Seen as a whole, The Mind Beyond is less concerned with proving ESP than with examining why we want to believe—or why we resist belief so fiercely. The plays circle themes of communication, isolation, mutation, and transcendence. They ask whether the limits of the five senses are genuine boundaries or merely habits of thought.

Stylistically, the anthology format suits the material. Each episode adopts a different tone—psychological realism, speculative drama, quasi-scientific thriller—mirroring the uncertainty of its subject. The lack of definitive answers is not a weakness but a structural principle. ESP, after all, resists laboratory neatness.

If the series has a flaw, it lies in the inevitable unevenness of anthology drama. Some plays persuade more through character than concept; others lean heavily on debate. Yet this unevenness is part of its texture. Like the phenomenon it explores, The Mind Beyond flickers between revelation and doubt.

Ultimately, Shubik’s gamble was not that audiences would leave convinced of telepathy or second sight. It was that they would recognise the dramatic power of the question. In bringing ESP “to the dramatists and actors,” she created a forum where mysticism, psychology and speculation could meet under the sober lights of BBC drama. Whether one believes in the singing of the universe or the hallucinations of the lonely mind, The Mind Beyond makes the unseen feel theatrically alive.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 15th, 2026. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.