Dinosaurs

1991 - United StatesEvery so often, a television show comes along that is truly unexpected and unique. Dinosaurs was the brainchild of the great Jim Henson, beginning work in 1988 - one of his last projects before he passed away in 1990. Walt Disney's television department greenlit the series that year, with Henson's son Brian taking over the Jim Henson Company and finally bringing the series to the screen. Michael Jacobs and Bob Young, known for their work on Boy Meets World and My Two Dads, headed a writing team of sitcom stalwarts, and were listed as the show's creators.

Having revolutionised puppet shows with The Muppet Show, Jim Henson had been impressed by the then-cutting edge animatronic technology on display in films such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and sought to use this to create his vision of a sitcom about a family of dinosaurs. (Several Turtles live action performers later performed under the latex on Dinosaurs, with a number of Muppet veterans operating the puppets and animatronics.) The technical feats of the series were incredible. Each episode featured a cast working in huge dinosaur costumes with impressively expressive faces, backed up by more traditionally Muppet-like puppets and simple hand puppets for the creatures that were less in the limelight.

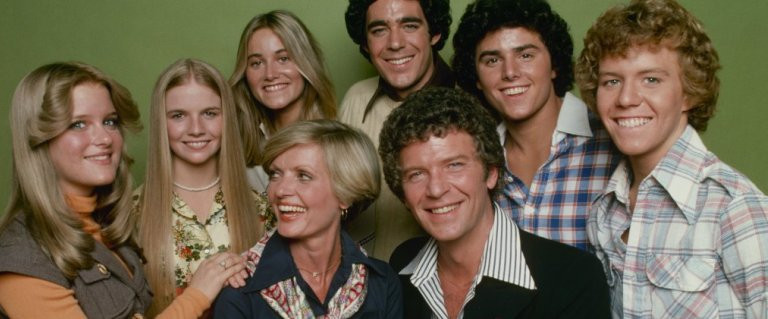

The series was set in the year 60,000,003 BC. Any schoolchild will notice that this is actually about five million years after the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs, but (pre)historical accuracy was hardly what the show was going for. In spite of being about the lives of a bunch of ravenous reptiles, the series was structured as a traditional American sitcom, with a reassuringly normal family at its centre. They just happened to be large, green and scaly. The Sinclair family (named for the Sinclair Oil Corporation, which has long featured a dinosaur on its logo) is made up of six dinosaurs of different species (how this works is a bit of a mystery as well). While the hard work was done by the people within the bulky costumes and the further people operating the heads, it's the phenomenal voice cast who made the biggest impression.

Earl Sinclair, the mighty Megalosaurus, is the head of the household, an overworked, overweight average Joe who works for economic conglomerate the Wesayso Corporation as a tree pusher (felling trees to make room to build, with the result of making coal for the future, one of the cleverer jabs at the fossil fuel industry). Voiced by Stuart Pankin (Not Necessarily the News, Curb Your Enthusiasm), Earl is pretty simple and highly suggestible, but altogether a good dad who works hard at a job he hates to support his family.

His wife Fran (allegedly an Allosaurus, although she looks more like a Dilophosaurus to me) is the homemaker, the stereotypically sensible one of the family, who Earl rarely listens to but invariably turns out to be right. She's voiced by the late, great Jessica Walters, the prolific screen actress best known for Archer and Arrested Development. Fran bears the brunt of Earl's hairbrained ideas, but when she decides that something needs changing or that she wants something more from life, she'll pursue it relentlessly whatever the consequences.

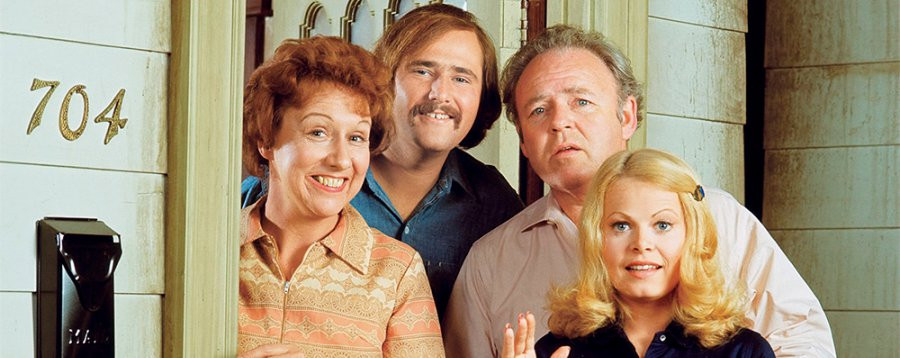

Fran and Earl have two teenaged kids, Robbie and Charlene. Robbie, a Hypsilophodon, is the eldest, a pretty decent sort who is surprisingly feminist in his outlook but is concerned with his low popularity and poor track record with girls. Charlene, a frilled Protoceratops, is younger, obsessed with sweaters and her appearance, but is on the cusp of becoming an activist throughout the show, learning just who she is. They are voiced by Jason Willinger (predominantly a documentary narrator since the series ended) and Sally-Anne Struthers (who won awards for her work on All in the Family and Gilmore Girls).

Finally, and unforgettably, is Baby Sinclair, a dumpy pink hatchling who needs constantly to be the centre of attention. Voiced and operated by veteran Muppeteer Kevin Clash (recognisable straight away as Elmo from Sesame Street), Baby adores his mother, and relentlessly bullies Earl, his “Not-the-Mama.” While Baby's violent saucepan attacks on Earl were put in for the kids, his stories lead to some surprisingly sweet and touching moments, and he was the most popular character on the show by far. Indeed, Jacobs noted in interviews that the ongoing popularity and marketability of Baby is what let them continue making the show for four seasons.

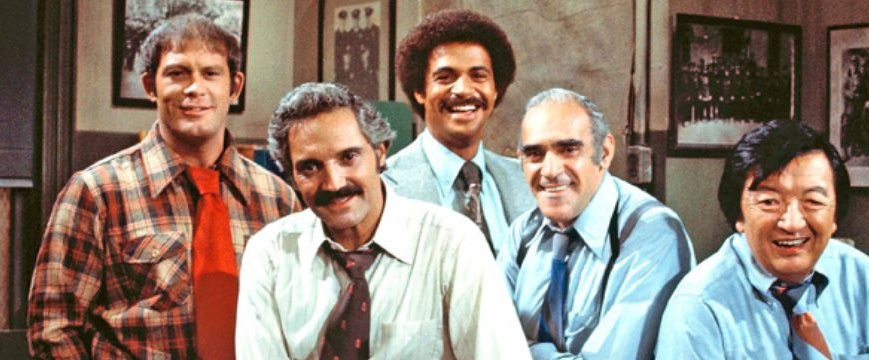

There are, of course, many other recurring characters. Sam McMurrey (Freaks and Geeks) voices Roy, a T. rex who works with Earl as a tree-feller and is his best friend, and concerningly, Earl is the brains of the pair. Their boss, B. P. Richfield (Sherman Hemsley – All in the Family, The Jeffersons), is a huge and terrifying Styracosaurus who bites his employees' heads off if they make him angry – literally. Suzie Plakson (best known for various roles in the Star Trek franchise) voices Monica Devertebrae, a blue Brontosaurus who is the Sinclairs' neighbour and Fran's best friend. The only quadrupedal dinosaur in the series, Monica presents herself by sticking her head and neck through the Sinclairs' kitchen window, operated by a team of puppeteers. The laconic and sarcastic Monica is the voice of reason in many an episode, and has to suffer Roy's deep and abiding infatuation. Other characters include Spike (Christopher Meloni – Oz, True Blood), a Fonz-like dropout who befriends and influences Robbie; the newscaster Howard Handupme (a hand puppet, naturally); and Fran's mother, the cantankerous Ethyl (Florence Stanley – Barney Miller, My Two Dads) who is wheeled around in a bathchair.

Many of the dinosaur costumes and puppets were reused again and again for one-off and background characters, an obvious but effective cost-cutting measure. The flipside of this is that the series could afford an incredible array of guest voices, many of whom reappeared as various characters throughout the show: Michael McKean (Clue, Better Call Saul, Good Omens), Jason Alexander (Seinfeld, Coneheads), Michael Dorn (Star Trek: The Next Generation), and Tony Shalhoub (Monk, Galaxy Quest) to name a few. And, of course, the unmistakable tones of Tim Curry, in no fewer than seven roles over as many episodes.

It's easy to watch Dinosaurs as a simple sitcom, enjoying the absurd imagery of prehistoric creatures acting as a modern American family. For kids, in particular, the monster costumes and slapstick are entertaining enough, and it's easy to see why many viewers dismissed it as a children's show. Dinosaurs, however, is far, far cleverer than that. As well as poking fun at the traditional sitcom by recreating it as a monster-fest, the series is one of the most cuttingly satirical programmes of the Nineties. Its closest relative is, undoubtedly, The Simpsons, with the Sinclair's being essentially reptilian versions of the Simpsons family, and with both series using the same tactic of an outwardly kid-friendly medium to hide a biting social commentary. While Henson conceived of Dinosaurs before The Simpsons aired, it's generally accepted that without the success of the yellow-skinned cartoon family the prehistoric sitcom would never have been greenlit. It was simply too weird an idea to finance until someone did something similar on a lower budget and made it work.

Across four seasons, Dinosaurs touched on a variety of issues that are as important and meaningful today as they were in the Nineties. “I Never Ate for My Father” sees Robbie give up carnivory in favour of vegetarianism, but this is used as a metaphor for gender norms, homosexuality and the fear of counter culture, with Earl angry that his son isn't “carnivorous enough” to be a man. The fantastically-titled “What 'Sexual' Harris Meant” sees Monica dealing with chauvinism and harassment in the workplace. Themes of racism, xenophobia and border control rise repeatedly in the relationships between the two-leggers and the four-leggers, reaching a head in the two-part story “Nuts to War” (with the newly-invented WAR standing for “We Are Right”). A later episode even touches on interracial marriage and the green card debate, with Roy willing to marry Monica to save her from deportation (“You've got two legs, she's got four. Think of the kids – they'll have three legs!”)

Further episodes deal with animal rights and the rights of indigenous peoples, in the form of the simple, put-upon cavemen (it's very much a Flintstones view of prehistory), who are as primitive or as sophisticated as an individual story requires. “The Greatest Story Ever Told” addresses Creationism as an alternative to science, with a new religion called “Potato-ism” being taught as the truth in schools, while “Charlene's Flat World” sees the young dinosaur on trial for heresy for suggesting the Earth is round. “Steroids to Heaven” deals with peer pressure and drug abuse; “Power Erupts” is one of several episodes that attacks the corruption and misinformation of the energy industry; and “Network Genius” skewers television itself.

Environmental messages were often the theme of the series, never more powerfully than the final episode, “Changing Nature” (although network shenanigans meant it was shown out of order on first broadcast). In this episode, Wasayso wipes out a species of insect by building over its spawning ground, beginning a chain reaction that devastates the fragile natural order. Each time the corporation, with full government backing, tries to fix the problem it only make it worse, all the while celebrating the increased profits they see as a result. When the vines the beetles eat run amok and threaten to engulf civilisation, the company uses a defoliant that wipes out all plant life. To try to bring the plants back, they trigger volcanic eruptions, figuring that the clouds of smoke will lead to rain. The series ends with the worldwide smog leading to a volcanic winter, dooming the dinosaurs to a slow, cold death – but at least blanket sales are through the roof.

While ending a series about dinosaurs with their extinction may seem obvious, the astonishing bleakness of the episode is really something else. A furious attack on corporate environmental damage, the ignorant misreading and dismissal of science, and the simple lack of foresight in putting profit ahead of sustainability, “Changing Nature” is more relevant today than ever before. It's a stunning ending to a show that never pulled its punches.

In hindsight, it's remarkable Dinosaurs lasted as long as it did. An incredibly expensive programme to produce, it was lucky to make it to four seasons, but in that time, the combination of bright, colourful, kid-friendly visuals and fearless, unflinching social commentary made it one of the most surprising, most affecting and funniest sitcoms of the time. Watched again, today, as people question society even more and the truth of our abuse of the planet becomes undeniable, it hits even harder.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 23rd, 2021. Written by Daniel Tessier for Television Heaven.