Food for Ravens

1997 - United Kingdom“no one involved in commissioning Food for Ravens could have expected an even-handed and objective analysis of Bevan's career”

Food for Ravens review by John Winterson Richards

On approving the proposal for this review of Food for Ravens, the Trevor Griffiths "biopic" of Aneurin Bevan for the BBC, our Editor joked that he assumed it would not be very political, adding a smiley face "emoji." While we strive to be strictly non-partisan, it is impossible to separate Bevan or Griffiths from their politics - and both of them would probably object to any attempt to do so.

Griffiths may in fact be the more political of the two. An activist as well as a writer, he seems to view his writing as a means to an end - but happens to be very good at it. His best works are not directly about politics, even if they retain an obvious political subtext. His most memorable play, Comedians, is about an evening class in "stand-up" comedy, not something one might associate with the serious-minded Griffiths: it turns out to be very unpleasant and corrosive, but it certainly sticks in the mind - even if one might prefer it did not. Based on his own experience with his first wife, Through the Night, one of Griffiths' contributions to Play for Today, chronicles the offhand treatment of a woman with cancer by the National Health Service, ironically an organisation for which Griffiths shows great deference in Food for Ravens.

Much of the rest of his work is more directly about politics. A lot of television writers wear their politics on their sleeves - almost invariably their left sleeves - but few are as overt as Griffiths about how important his political agenda is to his writing, and vice versa. He has been quoted as saying he cannot understand how a socialist writer would not devote much of his effort to television, despite the fact that he has also written plays and film scripts to great success.

He wrote "about 45%" of the Warren Beatty film Reds, which took a very sympathetic view of the American Communist John Reed, for which he won a Writers' Guild of America Award and was nominated for an Oscar (more surprisingly, it was also screened at the White House for the then President Ronald Reagan - who evidently enjoyed it: "a most imaginative job," he wrote in his Diary). His signature work for television is probably Bill Brand, an 11-part series about a predictably left-wing Labour MP in the 1970s. In The Last Place on Earth he took an aggressively revisionist line on the great British Imperial hero Captain Robert Falcon Scott that is not supported by the evidence. By contrast the episode he wrote for the historical drama Fall of Eagles is notable for its breathtakingly flattering portrait of Lenin, played by Patrick Stewart: it has not aged well in the light of subsequent historical research but even at the time it seemed a bit much. It is no surprise that Griffiths has also collaborated with Ken Loach.

It is therefore safe to say that no one involved in commissioning Food for Ravens could have expected an even-handed and objective analysis of Bevan's career. What they got was a bit too partisan for the BBC even in 1997. Despite having invested, according to the Internet Movie Database, an estimated £900,000 - when that was still considered a lot of money for a production - it was decided to restrict the broadcast to BBC Wales (Bevan is generally presented as a local hero in Wales and it was felt something should be done there to commemorate the Centenary of his birth). Lobbying by its globally respected star Brian Cox finally got Food for Ravens a full network broadcast, but only in a graveyard slot, just before midnight, with no publicity. Griffiths has not had a television commission produced since then.

It was therefore something of a surprise to see Food for Ravens repeated after disappearing for quarter of a century. The pretext was the 75th Anniversary of the establishment of the NHS when Bevan was Minister of Health. The short summary on the BBC iPlayer describes it as a "Drama profile of the Welshman responsible for establishing the principle of publicly funded healthcare 'from the cradle to the grave' - Aneurin Bevan" - an inaccuracy that is hardly Griffiths' fault but which is a fair reflection of the uncritically hagiographic line in his actual script.

That basic principle had in fact been agreed by all three main parties of the Wartime Coalition Government, Conservative, Labour, and Liberal, before Bevan became Minister of Heath in 1945. Contrary to legend, there was considerable public funding of healthcare before the War. Then in 1938, with War looming, the Emergency Hospital Service, in many ways the prototype of the NHS, was set up by the then Conservative Minister of Health, Walter Elliot. During the War, a Royal Commission, set up by the Coalition Government and chaired by Sir William Beveridge, a Liberal, recommended a permanent health service among other things. The principle of universal publicly funded healthcare was accepted on behalf of the Coalition by another Minister of Health, the Liberal Ernest Brown. The next Minister of Health, Henry Willink, a Conservative, began to put that principle into practice with detailed proposals in a White Paper, which recommended a decentralised structure involving local authorities, many of which had already established hospitals of their own. All three parties accepted the basic principle in their manifestos for the 1945 General Election, which was won decisively by Labour. It was only at this late stage that Bevan, a surprise selection for Minister of Health, got involved.

Bevan's contribution is therefore often misunderstood, or misrepresented, and Food for Ravens does nothing to correct the mythical version. Bevan insisted on junking Willink's decentralised model in favour of a highly centralised one, literally nationalising the hospitals established and run by local authorities, charities, and voluntary organisations. This stirred up controversy where there had been consensus, but, after much avoidable conflict and delay, he got his way, nationalising over 2,600 existing hospitals and, according to Nursing Times, 480,000 hospital beds - far more than there are in the NHS today when it is serving a much larger population.

Griffiths is not interested in facts that disturb his narrative. Instead, in the opening minutes, he imposes this cringeworthy exchange on to the lips of his principals which sets the tone...

Bevan: "I hate hospitals."

Jennie Lee: "Then you shouldn't have built so many."

The truth is that Aneurin Bevan never built a single hospital. The first purpose-built NHS hospital was put up several years after his time in office. If anything, Bevan reduced capital investment in hospitals, making it dependent on a single source, central government funding, where this had previously been supplemented by other sources, including local authority rates, voluntary insurance schemes, fees, legacies, and charitable fundraising.

This is only the worst of several misleading moments in Food for Ravens. One is forced to ask whether Griffiths was sloppy in his research or whether it was a deliberate choice to convey a false impression? Does it matter? Yes, because, as Griffiths would surely be the first to acknowledge, people are influenced by what they see on television. They tend to assume it is true, but Food for Ravens is at best a partial truth and sometimes plain agitprop.

Judged purely as drama, not as history, Food for Ravens is by no means without merit. It shows Bevan dying but being kept in ignorance of his condition by those around him - which actually happened. Informed by his experience of the death of his own father, Griffiths conveys the growing sense of the hopelessness of his situation very powerfully.

Griffiths obviously felt a particularly strong personal connection to the project. For the first, and last, time on television he directed as well as wrote, so there was no one to provide a check on his excesses as a writer. Some of his visuals are very strong, especially the countryside scenes around Bevan's home in Buckinghamshire, but, like many first-time directors, he tries too hard to impress. He shares a fault uniquely common among British directors, the need to make scenes set in Wales - a country used as a location by directors from all over the rest of the world because of its natural beauty - as gloomy as possible. His dialogue is stylised and, to be honest, a bit stagy. Trying to be profound, it comes across as pretentious. In fairness, Bevan always tended to talk as if he expected to be quoted, but, perhaps because he is Welsh, he is made to babble here like a second-rate Dylan Thomas - who is clumsily mentioned by name - and it all seems rather artificial, something a playwright would write, nothing a human might say.

There is no real insight here - about Bevan, about politics, or about dying. This is a great pity because, whatever one thinks of Bevan and his politics, he was a fascinating man - a ruthlessly ambitious, energetic, witty autodidact with a taste for celebrity lifestyle, a genuine passion to improve the lives of those he considered his own people, and a giant chip of his shoulder about everyone else - who would provide wonderful raw material for a more analytical drama.

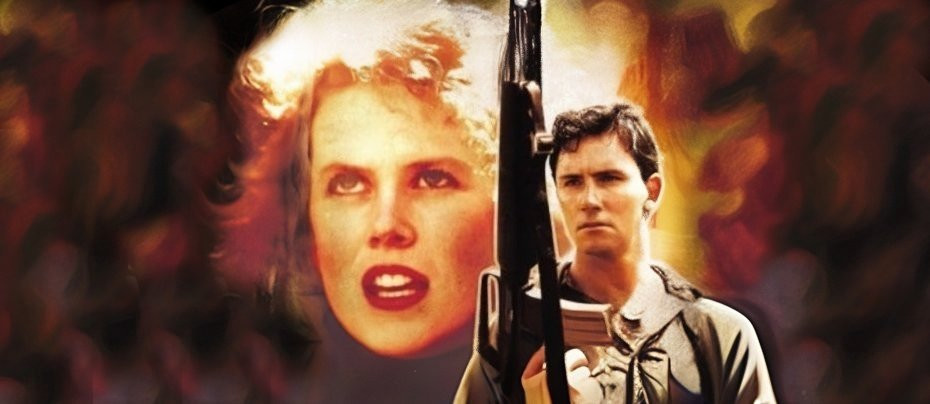

The only thing worthy specifically of Bevan's story in Food for Ravens is the casting of the two principals. The greatest compliment one can pay those consistently superb actors Brian Cox and Sinead Cusack is that one soon forgets that the Scotsman Cox does not look or sound much like the Welshman Bevan (whose natural speaking voice was not so good - like many great orators, he built his reputation as such because he had to work hard at it) and that the Irishwoman Cusack does not seem much like the Scotswoman Jennie Lee (Bevan's wife, who was herself a high profile Labour MP, a fact barely acknowledged in Food for Ravens).

All this having been said, it is regrettable that a writer of Griffiths' undoubted talents has not done anything for television since Food for Ravens. Political commitment should not exclude a writer, so long as some effort is made to put politically motivated works in their proper context, and so long as political commitment is not equated with a single point in the political spectrum. Griffiths is right to stand up for challenging ideas on television, but this must include ideas that challenge his own.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 20th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.