Guinevere

1994 - Lithuania UsaA Lifetime "television movie" that has been generally - and, for the most part, deservedly - forgotten, Guinevere is nevertheless worthy of note for three redeeming qualities.

First, it deserves credit for taking a different perspective on the old story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table by looking at them from a woman's point of view. It was not entirely original in this. The idea had been in the air since the publication, about ten years before, of Marion Zimmer Bradley's novel 'The Mists of Avalon,' which looked at the legends through the eyes of Arthur's half-sister, Morgaine or Morgan le Fay. This was followed a few years later by Persia Woolley's 'Child of the Northern Spring,' of which Guinevere is a very loose adaptation. In Guinevere the protagonist is Arthur's Queen and Morgan is her antagonist.

In traditional Arthurian literature, Guinevere is little more than a lust object, a MacGuffin who sets up the conflict between the King and his best friend, Lancelot. Her whole character description is "very good looking." Where she is actually allowed a personality, she is kind but something of an airhead, a trophy wife who keeps getting herself and others into trouble.

So a feminist take on her is actually a very good idea, and Lifetime, a channel which has women explicitly as its target market, was the obvious place to carry it off. However, the script was heavy handed in its feminism, mixed with anachronistic New Age pseudo-paganism, and the director's answer to Freud's great question "What do women want?" was apparently "Lots and lots of soft focus."

As a result, the whole thing was a conceptual mess from the start. Television viewers had to wait for a critically and commercially successful adaptation of 'The Mists of Avalon' in 2001 for a serious attempt at a feminist perspective on the Arthurian legends.

Yet Guinevere might still merit a footnote in the cultural history of feminism for its attempt to portray Guinevere as a Warrior Princess. This was the year before Xena Warrior Princess got it right, suggesting that this was another idea in the air at that point. Even so, it seems unlikely that Guinevere was much of an influence on Xena. We are told in the script that she is a trained warrior in the same way that we are told that she is a well read intellectual, but neither comes across in what we see. She is given an unconvincing victory in a sword fight against two men and that is it.

The second reason why Guinevere is of greater cultural significance than might now be apparent is that it is an early example of how quickly Western producers saw the potential of Eastern Europe as a place to make films after the end of the Cold War.

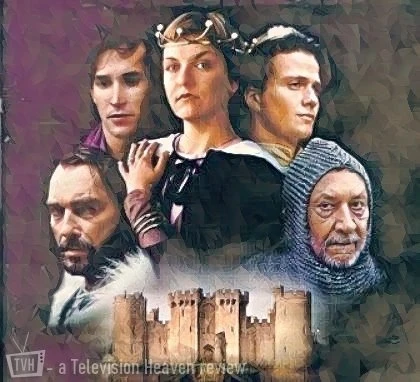

Lithuania looks more like the imaginary land of King Arthur than the actual land of King Arthur does. It has a lush, fairy tale quality to it rarely found even in Britain. Above all, Trakai Island Castle is an absolute star as Camelot. No matter that the historical Camelot would not have looked anything like it. No matter that it would have been considered strategically and tactically impractical in Wales. What matters is that this is how Camelot should look...

On a practical level, the low production costs in Lithuania allowed more of a sense of the epic than would normally have been possible in a "television movie" at that time. It has to be said that this is still not very epic, but a lot of extras, costumes, and props were available very cheaply after the fall of the mighty Soviet film industry. One criticism is that the quality of fight arrangement, even basic sword handling, is generally very low, which is surprising given that historical medieval combat has since flourished as a competitive sport in Eastern Europe.

The third and final positive point about Guinevere is the performance of Donald Pleasence as Merlin. Sadly, it is significant because it turned out to be one of his last roles, but at least it shows he remained at the height of his powers to the end, and it is a case study in how a great actor can rise above the most unpromising material and add a touch of class to the most lacklustre drama. He even gives Guinevere's name the proper Welsh pronunciation.

Merlin has always been a bit ambiguous. Although the character as we know it today is largely the literary construction of Christian monks, there has always been a touch of the dark side to it, and the fashion in recent years has been to exaggerate his links with a supposed survival of Celtic paganism, for which there is little real evidence in the 5th Century AD.

The Pleasence Merlin maintains that ambiguity rather cleverly. He is presented as a Christian Bishop who is knowledgeable about the pagan religion as it is suggested in Guinevere and respects her practice of it. He takes the line that it is the same God. He is above all a very human and humane Merlin. Although best known for his villainous or at least slightly sinister roles, Pleasence could also play sympathetic characters very effectively as he proved in The Great Escape and The Barchester Chronicles. Here he is almost a father figure to Guinevere and their scenes together are perhaps the only authentic personal moments in the whole film.

It should be noted, however, that two other actors, both British, also manage to emerge with their professional integrity intact by taking their parts more seriously than the script deserves.

James Faulkner pulls off an Alan Rickman by making the villain considerably more entertaining than the protagonist. His "Malgin, King of Gaul" seems to be mistranslation of the historical Maelgwn Gwynedd - North Wales or Gwynedd being known as "Norgales" in later Arthurian literature - whom some scholars consider the real life model for the literary Lancelot.

A young Anton Lesser steals his scene as Malgin's messenger to Guinevere: the script and direction have to give her the victory, but his sneer alone is enough to blow her off the screen.

To be fair, that is not difficult. Sheryl Lee in the title role would be a gift for the sort of reviewer who fancied building a reputation for witty remarks, but at a certain point it would begin to look like bullying, even if every word was true. Suffice it to say that from the moment her flat tones introduce the story in voiceover we know exactly what to expect.

When we get to see her, she is pretty in a slightly tomboyish sort of way but hardly the sort of beauty who starts a civil war between a noble King and his loyal right-hand man. Of course, this is supposed to be a feminist tract, and therefore all about how character is more important than appearance - even if it is still compulsory that she just happens to be quite good looking - which makes it all the more reprehensible that she lacks the slightest spark of intelligence or depth.

Guinevere tells us she has studied mathematics, astronomy, and Latin, and she is full of ideas and opinions. None of this is remotely convincing. One cannot help thinking of the many films made around that time in which the obvious bimbo whose only function was to fall into bed with the hero was supposed to be a brilliant neurosurgeon or a brilliant scientist or whatever. This was Hollywood pretending to offer strong role models for women when in reality it was another version of the male fantasy in which an intellectual and social delta could bed an alpha female.

In Miss Lee's defence, it is difficult to see how Dame Maggie Smith could have done much better with some of the lines poor Guinevere is given. Nevertheless, the total failure of the title character means that there is an emotional vacuum at the heart of what is meant to be an emotional drama.

The actors playing Arthur and Lancelot are simply forgettable - which is probably a kindness to them. Both are in any case side-lined and effectively emasculated. Arthur and his entire army are captured by Malgin, and they have to be rescued by an unlikely army of peasants led by Guinevere. The plot holes in that sentence alone would take too long to enumerate.

Anyway, we are at least all set for a dramatic final conflict between Malgin and Guinevere with the odds firmly in his favour. After all, the guy has beaten Arthur, and has him and his Knights just tied up over there. He has since been joined by some more Kings, and so he has a big army of fully armed and armoured professional soldiers against a bunch of yokels with pitchforks and the like. How can he possibly lose?

Then - spoiler alert, but frankly you are unlikely to watch this far, nor do we recommend that you do - he gives up. He simply surrenders to Guinevere because... because... er... well she appears to have bluffed him somehow into thinking she had a proper army, but it is not really clear, nor is it explained why it was enough for him to throw in the towel when he still had the army that had beaten Arthur and his Knights. Never mind. By this point we have ceased to care.

It was a suitably frustrating note on which to end a frustrating show. It was frustrating not because it was bad but because it could have been good. Pleasence, Lithuania, and a new feminist perspective on an old story could have been combined to deliver something really special. As so often, poor scripting and some bad casting choices wasted a great opportunity.

Review by John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 9th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.