Narcos

2015 - United StatesThis is how political drama should be done

‘Narcos’ review by John Winterson Richards

More like a historical epic than a standard police procedural, Narcos is the story of the dismantling of the original Medellin and Cali Cartels in Colombia in the 1990s. The most astonishing of many astonishing things about the three-season drama is how closely it sticks to known historical facts. Indeed, the greatest liberties appear to have been taken with the personal biographies of the two real life US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Agents Steve Murphy and Javier Pena, whose book described the main events, and who actually acted as consultants to the show, rather than with the events themselves.

In the Seventies and Eighties, Colombia, like much of Latin America, became a battleground between left wing terrorists and right wing vigilantes - at the very same time that an explosion in demand for cocaine in the United States led to a rapid expansion of the Colombian cocaine industry. Note that industry is the right word here. Cocaine was soon Colombia's most profitable export and a vital contributor to her Gross National Product, and as such well integrated with the mainstream economic and political system.

It was Ronald Reagan who sent a well funded army of US Agents South - two armies in fact, because they were fighting two separate enemies, the Marxists and the major drug smugglers, the "narcotraficantes" or "narcos." It soon became apparent that there was a conflict between the objectives of those two forces.

The situation was far more complex than the Americans had imagined. On paper, the left wing guerrillas, the right wing vigilantes, and the "narcos" formed a triangular balance of power. In practice they did not allow their deep ideological differences stop them making mutually beneficial arrangements when the occasion demanded it. The Anti-Capitalist guerrillas needed the American dollars they got from the drug trade in return for "protecting" cocaine processing plants out in the jungle. While they still sometimes clashed, 'Narcos' shows how they soon realised where the real power lay and learned there was more to be gained by co-operation than conflict with the Cartels. It goes on to show how they sometimes even made tactical alliances with the Medellin Cartel under Pablo Escobar, truly the unacceptable face of Capitalism who nevertheless posed as a friend of the poor like the leftists; he had open political ambitions and in the United States Government he shared a mutual enemy with the revolutionary left.

However, Medellin's alliance with the left served as a pretext for the rival Cali Cartel to make an equally cynical alliance with the right wing vigilantes - who were themselves funded, trained, and equipped by the Americans to fight the Marxists. So Narcos presents us a situation in which the United States Government is effectively allied with one Cartel in order to fight another. This is fictionalised but based on fact. No wonder the series begins with a reminder that the literary genre of "magical realism" originated in Colombia.

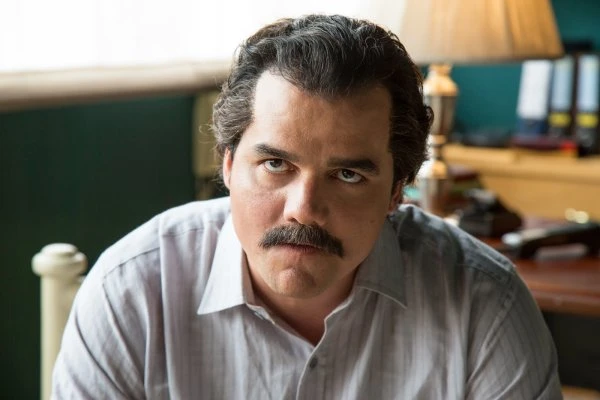

All this is dramatised expertly in Narcos, complete with a fine sense of time and place, and in particular a clever blending of modern photography with period news footage. It is divided into two distinct parts. The first two seasons deal with the Fall of Pablo Escobar, viewed mainly from his own point of view and that of DEA Agents Murphy and Pena operating out of the American Embassy in Colombia, with some minor character arcs to illustrate the human cost of the narcotics trade and its violence. It has the structure of an epic tragedy in which the tragic hero - in the literary sense of "hero," certainly not the moral sense - is brought down by his own character flaws. The second part, the final season, is a more straightforward police procedural in which the "Godfathers" of the Cali Cartel are tracked down in their turn. This is well executed, but, in the absence of Escobar's gigantic personality, slightly lacking in human drama, especially since the narration in the opening episode of the season gives it the air of inevitably.

The Escobar storyline picks up with Escobar already well established, indeed probably the wealthiest criminal of all time and on media lists as one of the wealthiest men on the planet. This attracts attention his colleagues in the Cartel feel they could easily live without. Escobar's vanity makes things worse when he runs for elected office: he wins - only for his political career to end in humiliation. In retrospect, this is the beginning of the end, but that end still takes a lot of time and effort. It has to be said that it might have been more dramatic to balance the Fall of Pablo Escobar with a bit more on the Rise of Pablo Escobar, on how the son of a poor farmer became one of the most powerful men in Colombia by his late twenties, and on the famously excessive lifestyle he enjoyed at his peak - but the production budget could only stretch so far.

Brazilian actor Wagner Moura gives us a wholly credible portrait of Escobar. There are times when he is even sympathetic. He is a caring father and a loving husband, if not always a faithful one. He seems sincere in his generosity to the poor. He attracts great loyalty, even devotion, from those around him. He has many of the qualities of a great leader, and one cannot help wondering if he might have achieved his fantasy of becoming President of Colombia if he had kept his cool and developed greater political sophistication (if that seems as unlikely as a dream sequence in which it happens, note that the actual President of Colombia at the time of writing was once affiliated with a terrorist group which collaborated with Escobar) - but then he would not have been Escobar, a man who rose to power through aggression and risk taking. This is the side of his character that comes out under pressure, and it is very, very ugly.

The forces ranged against him are represented by fictionalised versions of Murphy and Pena played by Boyd Holbrook (Hatfields & McCoys, The Sandman) and Pedro Pascal (Game of Thrones, The Mandalorian). They are helped and hindered by Eric Lange as the suspiciously laid back CIA Chief of Station who seems to be in control of everything, Richard T Jones (Terminator: the Sarah Connor Chronicles) as the FBI Attache, Patrick St Esprit as the Marine Colonel serving as Defence Attaché, Danielle Kennedy and Brett Cullen as successive US Ambassadors to Colombia, Raul Mendez and Tristan Ulloa (Warrior Nun) as successive Presidents of Colombia, German Jaramillo as a principled Attorney General of Colombia, Maurice Compte (Breaking Bad) as an honest but overly aggressive Colombian Police Colonel, and Juan Pablo Shuk and Gaston Velandia as more by the book Colombian Police Generals.

Other familiar faces include the great Luis Guzman as a Medellin boss, Damian Alcazar (The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian) as the more business-like Chairman of the Cali Cartel, Matias Varela (Easy Money) as his reluctant Chief of Security and Javier Camara (The Young Pope) as his arrogant Chief Accountant, Wayne Knight (Third Rock From the Sun) as a sleazy Florida attorney, and Edward James Olmos in another of his paternal roles.

The whole thing is carried on at a brisk pace, with some commendably tense sequences but also some sudden explosions of violence to demonstrate how apparently random death could be in Colombia when the War on Drugs became an actual war.

This brings us to the most impressive aspect of Narcos - how it encourages the viewer to think seriously about political issues by not being overtly political.

Without any apparent self perception, the Americans are shown as running the War on Drugs in Colombia directly, with the Colombian Government and Police as very much supporting cast. This may simply be because it is an American show and it is assumed that the principal market will want to see American heroes, but, whether it is deliberate or not, those heroes do not come off as particularly heroic. The Americans are shown as having practically taken over another country, a sovereign democracy, and wrecked it in order to solve a problem of their own making.

That problem is the demand for cocaine in the United States. Where there is demand there will be supply. If supply is disrupted, the only effect will be to increase prices. The figures quoted in Narcos itself suggest that the DEA's undeniable achievements against the Medellin and Cali Cartels did little to disrupt supplies. It shows why: the vacuum left in Medellin by the Fall of Escobar was filled almost immediately by a sensible professional who kept a lower profile.

Incidentally, estimated cocaine exports from Colombia in 2021 are considerably higher than the 1990s figures quoted in Narcos. Overall the War on Drugs is, so far, a predictable failure.

That failure has still come at a price. The Colombians themselves wanted to reduce the violence by agreeing deals with the Cartels, which did indeed have that effect. Two of these deals are shown as being sabotaged by our DEA heroes, leading directly to increased violence and the deaths of more innocents. Their motivation in this seems to be no more than a sanctimonious feeling that the "narcotraficantes" were not being punished sufficiently (in fairness, one did have a cat murdered by them, and your reviewer, a hardline animal lover, is all in favour of some substantial retribution on the guilty, but effectively starting a civil war in a foreign country seems to be stretching the John Wick Doctrine a bit too far). While there is a strong moral and practical case against such deal making, surely it was the Colombians' decision to make.

That they were stopped is typical of what Narcos shows of US influence in Colombia. American Ambassadors are shown bullying and manipulating Colombian officials, including elected Presidents, like Colonial Governors laying down the law to reluctant Native rulers, while the DEA Agents seem reminiscent of Colonial District Officers, treating the Colombian Police, who lost over 4,000 men, as unreliable local auxiliaries. One can see why many ordinary Colombians came to resent American interference in their affairs. In the end it is the honest Colombians who struggled against a corrupt system rather than the Americans who come out as the real heroes. If it was the intention of the producers and writers to prompt such thoughts without being obvious about it, then they are to be commended. This is how political drama should be done.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 1st, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.