From Gotham to Zeitgeist: The Evolution of Batman on Screen

Few fictional characters have reflected the shifting moods of popular culture as vividly as Batman. Since his first appearance in 1939, the Dark Knight has been reimagined countless times on both the small and big screens. Each incarnation—whether campy, gothic, or gritty—has told us as much about the era that produced it as it has about Gotham City itself. From the wartime serials of the 1940s to the neon excess of the 1990s, from Christopher Nolan’s post‑9/11 realism to Matt Reeves’ rain‑soaked noir, Batman has served as a cultural barometer. His cowl and cape may remain constant, but the anxieties beneath them are always changing.

When Batman first appeared on the cinema screen in 1943, he was not yet the billion‑dollar icon of modern Hollywood, nor the campy pop‑art crusader of 1960s television. He was something far more provisional: a pulp hero hastily adapted for a world at war.

The early 1940s were the golden age of the movie serial—chapter plays shown before the main feature, designed to lure audiences back week after week with cliffhangers and masked villains. Columbia Pictures, already successful with serials like The Spider’s Web and The Shadow, saw in Batman a ready‑made figure to join this tradition. Just four years after his comic book debut, the Dark Knight was drafted into service—not only as Gotham’s protector, but as a cinematic soldier in America’s propaganda war.

The result was Batman (1943), a 15‑chapter black‑and‑white serial that pitted the Caped Crusader against Dr. Daka, a Japanese spy armed with death rays and zombie henchmen. It was crude, cheaply made, and unmistakably of its time—yet it introduced elements that would become permanent fixtures of the mythos, including the Batcave and Alfred’s now‑familiar moustached appearance.

Six years later, Columbia returned with Batman and Robin (1949), another 15‑chapter adventure. This time, the enemy was not a foreign agent but “The Wizard,” a hooded villain wielding a remote‑control device—anxieties about technology replacing wartime paranoia. The production values were still threadbare, but the serials kept Batman alive in the public imagination, bridging the gap between his comic book origins and his eventual explosion into television stardom.

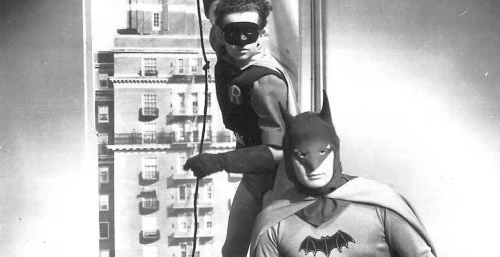

The 1960s Batman series is one of those rare television phenomena that managed to be both a parody and a cultural touchstone. On the surface, it was campy fun—bright costumes, tilted camera angles, and “Pow! Zap!” fight graphics. Gotham’s police were portrayed as bumbling, reliant on Batman’s intervention. This mirrored a growing scepticism about institutions in the 1960s, though softened into farce rather than critique. The show’s garish colours and stylized graphics echoed Andy Warhol’s pop art movement. It was a satire of mass culture at the very moment mass culture was accelerating.

But beneath the pop-art spectacle, it reflected the anxieties and contradictions of its era—nuclear dread, the Space Race, social upheaval, the Cold War, and political assassinations—while simultaneously capturing the public imagination in a way few shows ever had.

Instead of confronting the cultural issues directly, Batman offered a safe parody of danger. Villains were absurd rather than terrifying, turning the spectre of chaos into something laughable. Within weeks of its debut in January 1966, the show became a craze. Merchandise flooded stores, from lunchboxes to trading cards. A feature film was rushed into production the same year. For adults, the show worked as a parody of authority and superhero tropes. For children, it was straightforward adventure. This dual appeal made it a cultural lightning rod.

In a way, Batman was a victim of its own success: it had saturated the culture so completely that “Bat-fatigue” set in. The abrupt end of the 1960s Batman TV series in 1968 is a classic case of a pop culture phenomenon burning too brightly, too fast.

Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) wasn’t just a movie—it was a cultural reset for the character. By the late 1970s and 1980s, comics by Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams, and later Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One, had already re‑established Batman as a darker, psychologically complex vigilante. Burton’s film borrowed this darker tone but added his own baroque, almost horror‑tinged sensibility. The result was a Batman who was less detective and more avenging shadow. Michael Keaton’s Bruce Wayne was awkward, reclusive, and eccentric. His Batman was a creature of fear, using gadgets and theatrics to terrify criminals. This duality—Bruce as socially uneasy, Batman as commanding—was a major departure from both the comics and the 1960s TV show.

Burton’s Batman was willing to kill, something the comics of the time were moving away from. Production designer Anton Furst built Gotham as a nightmare metropolis, a mash‑up of Art Deco grandeur and industrial rot. He described it as if “hell had burst through the pavement and kept on growing.” Burton’s Gotham reflected real cultural fears of the late '80s: urban decline, corporate excess, and a distrust of authority. The film channelled those anxieties into a gothic fairy tale, making Batman not just a superhero but a response to a broken system. It didn’t just reflect the comics—it reshaped them. After Burton’s Batman, the darker, gothic interpretation became the mainstream image of the character, influencing comics, animation (Batman: The Animated Series), and every live‑action version since.

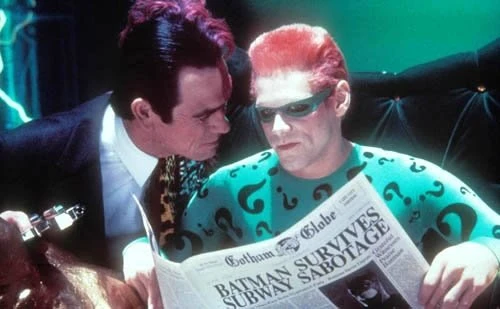

In Batman Returns (1992), Gotham became more grotesque and surreal, but Batman was less the focus—Catwoman and Penguin dominated the narrative, leaving Bruce as a brooding, reactive figure. The violence and sexual undertones (Catwoman’s sadomasochistic imagery, Penguin’s grotesqueries) pushed the film into darker, more adult territory. But in Batman Forever (1995), Joel Schumacher's direction set a lighter tone with campy villains (Jim Carrey’s Riddler, Tommy Lee Jones’ Two‑Face) and a more family‑friendly vibe. Val Kilmer took over as Batman. His Bruce Wayne was more polished, less eccentric, and more conventionally heroic. Gotham was redesigned as a neon‑lit, flamboyant city, moving away from Burton’s gothic decay. Robin (Chris O’Donnell) was introduced, shifting Batman from lone avenger to reluctant mentor.

Batman & Robin (1997) almost sank the franchise. George Clooney’s Batman was suave and quippy, but critics felt he lacked intensity. The film leaned heavily into camp and spectacle, echoing the 1960s series more than Burton’s noir. Gotham became a surreal toybox of giant statues, neon lights, and over‑the‑top set pieces. Batman was no longer a creature of fear but a team leader—with Robin, Batgirl (Alicia Silverstone), and Alfred all sharing the spotlight. The character lost his psychological depth, becoming a generic superhero weighed down by toyetic costumes. The decade ended with Batman in crisis—his credibility damaged by Batman & Robin. That failure directly paved the way for the franchise’s reboot in the 2000s with Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, which restored the darker, more grounded vision.

The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005–2012) is steeped in the cultural climate of the post‑9/11 world. Unlike the gothic fantasy of Burton or the neon camp of Schumacher, these films embraced a gritty realism that directly mirrored anxieties about terrorism, surveillance, and the moral compromises of security. Gotham was no longer a stylized set but filmed in real cities (Chicago, later Pittsburgh), grounding the story in a recognisable urban landscape. The villains’ tactics—bombings, mass panic, and symbolic attacks on civic order—echoed the imagery of terrorism. Batman became less a gothic avenger and more a counter‑terrorist figure, operating in a morally grey space where traditional institutions (police, courts, politicians) seemed inadequate.

Heath Ledger’s Joker wasn’t a criminal motivated by money or power—he was an agent of chaos, staging spectacular attacks to destabilize society. He targeted symbols of order (courts, hospitals, ferries). He used fear as a weapon, broadcasting threats through the media like a terrorist cell. His goal was psychological: to prove that under pressure, ordinary people would abandon morality.

In short, Nolan’s Batman films reframed the superhero myth as a post‑9/11 parable: a society under siege, struggling to balance freedom and security, order and chaos. Ledger’s Joker crystallized the era’s fear of terrorism—not as a political movement, but as a destabilizing force that thrives on fear itself.

Between 2016 and 2021, Batman’s cinematic story shifted into the DC Extended Universe (DCEU), where he was no longer a solitary figure but part of a larger, interconnected superhero world. This era was defined by Ben Affleck’s portrayal of an older, battle‑weary Dark Knight. Batman’s story became less about his personal crusade and more about his place in a shared universe and cultural mythos—oscillating between grim realism, blockbuster spectacle, and satirical self‑reflection.

The Batman (2022) follows Bruce Wayne (Robert Pattinson) in his second year of fighting crime in Gotham City, as the Riddler—now portrayed as a sadistic serial killer—begins targeting the city's elite. The Riddler is reimagined as a domestic terrorist archetype, radicalized online and using social media to recruit followers. The film suggests that alienation and resentment can metastasize into violent populism when amplified by digital platforms.

Directed by Matt Reeves, The Batman was more than just a reboot—it was a mission statement about where the franchise could go next. Instead of leaning into shared‑universe spectacle, Reeves carved out a self‑contained saga that suggested a slower, more atmospheric exploration of Gotham and its rogues’ gallery. The Batman is more than a detective noir—it’s a cultural mirror. The film channels the unease of the 2020s, layering Gotham’s corruption and decay with themes that resonate strongly with contemporary anxieties.

Reeves has described his vision as a multi‑film arc, with Part II in development and a third film planned to complete the story. After several delays, Part II is scheduled for release in October 2027.

Batman’s longevity lies not in a single definitive portrayal, but in his adaptability. He is less a fixed character than a mythic vessel—absorbing the fears, doubts, and aspirations of each generation. For some, he is a camp icon; for others, a brooding vigilante or a flawed detective. What unites these versions is their ability to hold a mirror to society’s unease, whether it be wartime paranoia, nuclear dread, urban decay, terrorism, or systemic collapse. In that sense, Batman is not just a hero of Gotham, but a hero of cultural reflection—forever reminding us that the shadows we fear most are often our own.

Published on October 1st, 2025. Written by Percival Wexley-Smith for Television Heaven.