The Rise and Fall of the Female Action Hero

From Xena to Millennial Galadriel

We all say silly things from time to time. It is therefore easy to forgive Jennifer Lawrence's absurd claim that she was the first woman ever cast in the lead of a major action film. However, there is an old saying about holes and digging. Less excusable was her subsequent claim that, before her stunning and brave smashing of the glass ceiling in The Hunger Games (2012), there was a strong body of opinion that said it could never be done because a male audience could never relate to a female protagonist, and so our pioneering Jennifer felt satisfaction every time that "lie" was disproved by those following in her distinguished footsteps. That was not only nonsense but dangerous nonsense. That any such "lie" was ever widely believed is itself a lie.

The truth is that audiences, even when in genres where they are traditionally male, have always been receptive to female action heroes. Women relate to them because they are women and men find them attractive for the same reason. Producers have always been well aware of that fact, even if they have sometimes been cautious about testing it to its limits.

The name mentioned most often in the avalanche of derision that followed poor Jennifer's "misspeaking" was, of course, Sigourney Weaver, whose character of Ellen Ripley in Alien (1979) was indeed revolutionary - a realistic portrait of a realistic working woman forced by circumstances to access her inner action hero. Ripley was followed by a number of similar female heroes in 1980s films: the name mentioned second most frequently in rebuttal of Lawrence was Linda Hamilton's Sarah Connor in The Terminator (1984), another realistic "ordinary" woman with no superpowers or special training who pushes herself to become a formidable fighter in order to survive and protect her child. Her story was later developed very intelligently on television in the underrated Terminator: the Sarah Connor Chronicles (2008) with Lena Headey as Sarah and Summer Glau as a mostly friendly Terminator. Quite apart from her significance as a female protagonist, Sarah remains a classic example of how character arc should be driven by plot.

Other 1980s female action heroes belonged to a different tradition. The 1980s, especially the early part of the decade, were also the Golden Years of the "Sword and Sorcery" genre in cinema. Most films had some form of woman warrior, if not necessarily in the lead then at least among the principals, and prominent on the posters, most notably Sandahl Bergman in Conan the Barbarian (1982), Lana Clarkson in Deathstalker (1983), and Brigitte Nielsen as the eponymous Red Sonja (1985). Many of these projects were based on "comic books" or "pulp" fantasy novels in which such characters were not uncommon. Since their readership was principally young males, they were usually illustrated in a prurient style, dressed, if that is the word, in outfits that look impractical for their supposed careers as professional fighters. This is reflected in Clarkson's costume in Deathstalker, which consists of a short cloak, boots, and hardly anything in between. Neither would Clarkson's method of disposing of a rapist in Barbarian Queen (1985) find favour in these post-"Me Too" times. It is therefore no surprise that these female action heroes have been airbrushed out of the received version of the progress of women in the entertainment media, but they are nevertheless an important part of the story.

They are in turn the product of an even older tradition. Once one starts looking, there is no shortage of female fighters in film before Ripley, even if they were usually presented as novelties. The ever-feisty Maureen O'Hara buckled a swash with the boys in The Sons of the Three Musketeers (1952) and Jane Russell's gunslinger protected Bob Hope in Paleface (1948) and Son of Paleface (1952), early examples of the now very common trope of the masterful woman being contrasted with the wimpy male. In China and Japan, the nature of the martial arts and some historical precedent made the notion of a trained female fighter more credible, and they were a mainstay of East Asian cinema from the 1960s on. Some Westerners, most notably Cynthia Rothrock, studied those martial arts and starred in the "kung fu" films that became increasingly fashionable in the West. Although mainstream Hollywood was slow to catch on, the concept of the female hero in a martial arts film was soon familiar to audiences as the growth of home video popularised action films from Hong Kong and Japan.

It could in fact be argued that the female action hero goes back all the way almost to the beginning of cinema. In D W Griffith's Judith of Bethulia (1914), the eponymous Judith, played by Blanche Sweet, decapitates an Assyrian commander, even if it should be noted that he is drunk at the time and the whole point is that she is not a warrior.

The film is based on an Apocryphal Book not included in the Old Testament, which illustrates that there are many very old traditions of warrior women in Western culture predating the invention of cinema, and later television. The Viking legend of "shield maidens" is discussed in my review of Vikings. Most famous of all are the Amazons in Classical Greek literature: there is some evidence to suggest that they had a basis in fact, possibly a tribe of women who were forced to defend themselves after losing all their menfolk in battle - if so, they do not appear to have survived for long. The sad truth is that literary tradition outruns historical reality in this respect. While there are well attested examples of women of high status, such as the Judge Deborah in the Bible, Queen Boudicca of the Iceni, and Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, leading men to war, it was almost unknown for women to fight alongside men in the battle line. Quite apart from the obvious cultural limitations, the nature of Ancient and Medieval warfare demanded a degree of bulk and physical strength which few women could attain. Women might join the fight in a desperate situation - there are many significant cases of them throwing things from the ramparts in a siege - but the notion of them openly and routinely taking the field on equal terms with the men, as some recent productions suggest, is historically and tactically absurd.

While the film industry, influenced by literary tradition, was therefore well aware of the potential of female action heroes decades before Jennifer Lawrence, she might have been on slightly stronger ground had she been talking about television. Of course, by the time of which she was speaking, the start of the 2010s, the female action hero was well established on television - by that late stage possibly even more than she was in cinema - but it cannot be denied that television took its time to get there.

The fact that the woman action hero was usually presented in film as a novelty or a subversion of expectations rather counted against her transference to television. Could a novelty like that sustain an ongoing television series, especially in the days when seasons were considerably longer than they are now?

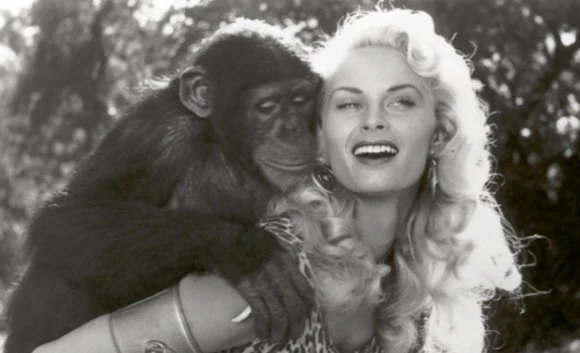

The early signs were not encouraging. Arguably the first successful show with a female action hero in the lead was Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (1955), starring Irish McCalla in the title role. Based on a "comic book" character who pre-dated Wonder Woman, it ran for only 26 episodes. The fit, statuesque McCalla had no previous acting experience: she seems to have been selected for her athleticism after being "discovered" throwing a bamboo spear on Malibu Beach; she later admitted, disarmingly, "I couldn't act but I could swing through the trees." It was clear that the idea of a female protagonist in an action show was still being treated as a novelty. Sheena and McCalla are nevertheless remembered fondly by those who watched it, and it proved to be influential on the producers of Xena: Warrior Princess three decades later, possibly via the 1984 film remake starting Tanya Roberts who had previously starred in the "Sword and Sorcery" classic The Beastmaster (1982).

It was the supposedly stuffy old Brits who really got the female action hero off the ground with Honor Blackman as Cathy Gale, PhD, and Diana Rigg as Emma Peel in The Avengers (1961). These were both women trained in the martial arts who were more than capable of looking after themselves and were fully the equal of their male co-protagonist, John Steed, played by Patrick Macnee.

It took American television a while to catch up, but the 1970s saw Angie Dickinson in Police Woman (1974), Lynda Carter in Wonder Woman (1975), and Lindsay Wagner as The Bionic Woman (1976), all pre-Ripley. Television had overtaken cinema, even if the repetition of the word "Woman" in the titles does suggest an element of novelty remained in the producers' subconscious. It could be argued that it took Cagney & Lacey (1982) introduce a genuine feminine sensibility into television action drama.

Meanwhile the Brits remained ahead by introducing the idea of a woman as a specialised fighter, not just someone who could defend herself at need, in Blake's 7 (1978) in the person of Soolin, played by Glynis Barber, and possibly also, to an extent, Dayna, played by Josette Simon. These were distinctively women warriors in a science fiction setting. In no other genre would they have been possible at that point, fantasy then not being considered respectable as adult drama by the people running television.

By the 1980s there was nothing unusual in the idea of a woman as a principal character in a British or American action show. Indeed, it was becoming almost compulsory to have at least one in the main cast. Yet there remained the question of whether a woman could hold the leading role in an action show in which she was a specialist fighter like Soolin. The fact that such a character might do so for an hour or two in a feature film was no guarantee that she could keep the viewers coming back week after week on television.

Although the relatively cheap production, the now dated effects, and the huge variation in the quality of the scripts mean that it has not aged well, Xena: Warrior Princess (1995) deserves to be remembered as the show that changed everything in this respect. In its way it was as revolutionary as The Avengers and Ellen Ripley. Xena was the first woman on television who actually looked like she could hold her own in close quarter combat and persuade men to follow her into battle. She was also an interesting and complex character who could sustain the viewer's interest over several long seasons.

Sam Raimi and Robert Tapert, the producers of The Evil Dead (1981) who went on to produce Xena: Warrior Princess have acknowledged the influence of Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, but one can also see the influence of the sort of characters played by Bergman, Clarkson, and Nielsen in those early 1980s "Sword and Sorcery" films. Since Raimi and Tapert were young men at the time, and were doubtless aware of Tanya Roberts through the feature film remake of Sheena, it is hardly a stretch to assume they were familiar with Roberts' other work in The Beastmaster and therefore with other films in the S&S genre around that time.

The difference between Xena and the 1980s warrior women is that she is given more depth. This is, of course, the great advantage that television has over cinema as a medium, that it has more time to expand, but it also has to said that Lucy Lawless, who plays Xena, turned out to be a more versatile actress than Bergman, Clarkson, and Nielsen, or at least was given more time and material to demonstrate her versatility - the better Xena scripts being very good indeed, even if the worst were very bad.

Lawless was in fact a last minute third choice to play the role after one preferred candidate had an accident and another became pregnant. A relatively inexperienced actress at that point, she seems to have been selected, like McCalla, mainly because she looked the part - tall and with the robust appearance of a healthy New Zealand outdoorswoman - but she was able to turn what could have been a novelty "spin off" from Hercules: the Legendary Journeys (1995) into a character of immense influence, and not just on television.

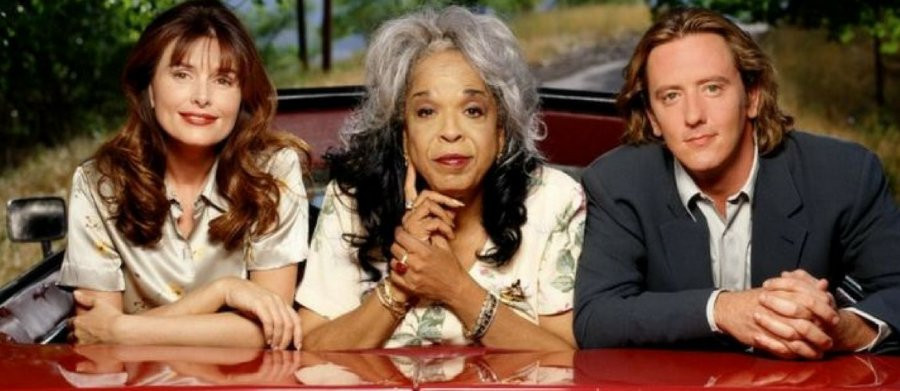

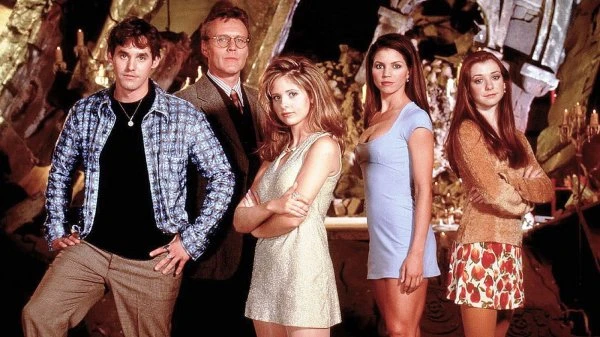

The commercial success of Xena: Warrior Princess was definitely a factor in Joss Whedon getting his television version of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997) off the ground, and Whedon himself has mentioned it positively, in spite of the fact that his character of Buffy is "older" than Xena: she first appeared in a 1992 film which Whedon had scripted but not produced, leaving him dissatisfied and eager to put the character in a project worthy of her. To a great extent it was Xena who gave him that opportunity.

His concept and casting strategy was different from Raimi and Tapert's. For the title role, he selected Sarah Michelle Gellar, who was already a seasoned veteran actress in spite of her youth but who lacked Xena's formidable physical presence. The whole point was that villains would underestimate her and audiences would find it easier to relate to her.

At the time of writing a number of allegations by people who worked with Whedon have given the impression that his loudly trumpeted feminism was grossly hypocritical, but this does not alter the fact that his contribution to the way women are portrayed on film and television remains significant to this day. The portrayal of every female action hero over the last twenty years owes something to Buffy or Xena or both. Of the two, Xena gets the credit as the first to plant to flag, but Buffy may have the more enduring influence because her show was a slicker production which has stood the test of time better than Xena's.

Both Xena and Buffy were cited as influences by Quentin Tarantino on Beatrix Kiddo, "The Bride, played by Uma Thurman in his Kill Bill (2003). Lawless' stunt double, Zoe Bell, also doubled for Thurman in the film. It was the best of an avalanche of action films with female leads that dominated the next decade unnoticed by the young Jennifer Lawrence. These included Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001) starting Angelina Jolie, Resident Evil (2002) starting Milla Jovovich, Underworld (2003) starting Kate Beckinsale, Elektra (2005) starting Jennifer Garner, Aeon Flux (2005) starring Charlize Theron, and DOA: Dead or Alive (2006) starring Jaime Pressly, Devon Aoki, and Holly Valance. Aoki also had a memorable supporting role as a female killing machine in Sin City (2005), one of many women who were portrayed as very good at fighting in that film and in films generally around that time. In was only towards the end of this fertile decade for female empowerment that Jennifer Lawrence came along in The Hunger Games - itself a film based on an already successful series of novels that might itself be a product of the greater acceptance of female protagonists that began with Xena and Buffy.

Meanwhile something similar was happening on television. There were more female protagonists headlining action shows, such as Alias (2001), notable as the production in which Jennifer Garner first made her mark, and women characters, both principal and supporting, began to be portrayed as fighting successfully alongside and against men as a matter of routine. This was happening not only in fantasy and science fiction shows but in historical drama like Vikings (2013) and even in contemporary action shows.

It was at this point that the reaction began. It is not - contrary to what some people in "The Industry" are claiming increasingly, and somewhat defensively, these days - a political reaction. Hardly anyone is bothered about women being protagonists, and indeed It is hard to find much solid evidence that anyone ever was. It is rather a growing scepticism among viewers who find that the notion of women and men fighting on equal terms interferes with their suspension of disbelief. To an extent - but only to an extent - they are prepared to go along with it in fantasy, because it is, well, fantasy. It is also just about credible in science fiction because combat in that genre is generally more reliant on technology, which may be assumed to be equally accessible to men and women. However, in historical drama it is contrary to established fact and in contemporary drama it is contrary to what is likely to happen.

A trained fighter like Cynthia Rothrock or Gina Carano really could take down an untrained or poorly trained man who tried to attack her, no doubt, and this gives their on screen fights a credibility most lack. Yet it should be emphasised that they are far from typical. Women's self-defence courses teach women how to disable male assailants quickly and effectively - and then to run immediately for help before the man can recover. The basic fact remains that men are, on average, bigger, stronger, and more aggressive than women, and, given even an approximate equality of training, experience, and fitness, a man is far more likely to prevail in any sort of fight with a woman. This is an unpleasant truth, but denying it can be dangerous. More to the point, it strains credibility beyond breaking point to see a slightly built woman who seems to have no idea how to carry herself defeat several male attackers at once.

This is not to say that women cannot beat men, only that it is extraordinary - which is, of course, why it is considered heroic - and there usually has to be some credible explanation for their victory. Buffy has a number of superhuman abilities that came with her "Slayer powers" and Xena is an experienced warrior who is revealed to have studied various useful techniques in her past. More recently, Jessica Jones, played by Krysten Ritter in Jessica Jones (2015), has Marvel "superpowers," and Brienne of Tarth, played by Gwendoline Christie in Game of Thrones (2011), is a very big girl who really does look like she could wear armour and swing a sword better than most men. Once such an explanation is given, disbelief can be suspended and the fight scenes enjoyed. Without it, the whole thing starts to feel like wishful thinking on the part of ideologically motivated writers and producers.

At the same time as this viewer scepticism about the practicalities has become more widespread, there has been criticism of the concept of the warrior woman from a completely different direction. It is basically a feminist critique, even if not all who ask these questions are feminists. Why does a woman have to adopt the male definition of strength to be considered "strong"? Why should a woman have to be as physically tough, aggressive, and skilled at violence? Are those traits in which women, on average, excel more than men, like emotional intelligence, intuition, versatility, and nurturing, not to be considered strengths?

The ideal is therefore a female action hero who retains her femininity. Few do. Buffy remains one of the best examples of how to get it right. She is a brave and skilful fighter, but she is not invincible. She is vulnerable, both physically and emotionally. She often makes mistakes and sometimes she is defeated. Yet always she finds the strength to stand and fight again. We see her humanity in this. We like her and admire her not in spite of her vulnerability but because of it.

Over the course of seven seasons, Buffy develops, gradually, almost imperceptibly, from a flippant teenager into a reluctant leader. If the strengths she exhibits as a fighter are traditional male strengths, her strengths as a leader are those traditionally associated with women. She really cares about others and seeks to protect them. She is still a young woman but her instincts are those of a mother.

The same is true of Ripley, Sarah Connor, and Xena, and most of the best female action heroes, whether or not they are actually mothers. In Alien Ripley protects her cat as if it was her child and in the sequel, Aliens (1986), she defends an actual child. It is motherhood that compels Sarah Connor to turn herself into a skilled fighter. Despite a lot of speculation as to the nature of her relationship, Xena is essentially a substitute mother to her companion Gabrielle, and also, to an extent, to their friend Joxer. It is this caring, nurturing, maternal side that makes them a lot more likeable than they would otherwise be and far more interesting as people than most male heroes.

Compare them to a recent example of how not to do it. The character of Galadriel in The Lord of the Rings: the Rings of Power (2022) has little in common with the Galadriel of Tolkien's books and Jackson's films. She is more of a Millennial take on that Galadriel.

Like practically all recent female action heroes, Millennial Galadriel is "better than the boys" at everything - to the extent that she is almost invincible in battle. Quite apart from the issue of credibility, this destroys all dramatic tension in her fights. There is no jeopardy. We know she is going to win. So does she. In battle, or when supposedly "training" recruits, she shows off, and there is a distinct air of smugness about her. She exhibits no hint of vulnerability, so there is nothing with which we sympathise.

She is indeed the equal, or the superior, of any man, but she does not balance this with any of the feminine characteristics that make the great women warriors great leaders. She is totally egocentric. She treats her subordinates, and practically everyone else, like dirt. It simply does not occur to her that, instead of showing a bunch a nervous young recruits how much better she is than them at fighting, true leadership might seek to build their self confidence. She has no insight into other people because she does not care about them.

She is certainly the equal, or superior, of any man in the traditionally masculine trait of extreme competitiveness - not realising that it is itself a sign of weakness. One might be reassured if one thought the writers understood that, but, looking at the lack of depth they brought to all the other aspects of The Rings of Power, this seems unlikely.

It seems that we are positively overwhelmed these days by legions of women warriors, all "better than the boys." No project is complete without at least one. Sadly, there are far more like Millennial Galadriel than like Buffy or Xena. It is becoming tedious. It is also undermining the very message of female empowerment such characters were meant to be convey.

Speaking as one who is, as should be clear by now, a huge fan of female protagonists in action shows - when they are done right - perhaps the time has come for "The Industry" to pause for breath and take stock of the tropes that have built up over the last couple of decades. Women action heroes still have an important part to play as role models, and they often make more interesting protagonists than male heroes, but the emphasis should be on quality not quantity.

To that end, here are three principles that producers and writers might want to consider before weighing down an action show with poorly conceived female characters who look unrealistic and tokenistic.

First, any hero, male or female, is dull and uninteresting if he or she comes across as invincible and invulnerable. It is not a betrayal of feminism to portray a woman as struggling, quite the contrary. Nor is it misogyny to show that there are many kinds of strength, not just physical strength. A woman who overcomes obstacles with great difficulty is a better role model for young girls than a perfect "superhero" who cannot be beaten.

Second, women are in general emotionally deeper and more complex than men, which makes them potentially more intriguing as protagonists. So why not use this advantage instead of simply giving an attractive woman the personality of a brutish man, which is how most warrior women on television now seem to be constructed?

Third, while it is progress that female protagonists in action shows are no longer a novelty, they may have gone too far the other way and become cliches. A subversion of expectations is no bad thing in itself. The first episodes of both Xena: Warrior Princess and Buffy the Vampire Slayer begin with a man menacing a woman - only to find out that things do not go as he expects. They were good dramatic moments. Such scenes are now longer possible, because the 21st Century viewer expects the woman to beat the man almost automatically.

Something has been gained and something has been lost. If everyone is extraordinary, then no one is extraordinary. Perhaps the best way to revive the female action hero is therefore to have fewer of them.

Published on January 9th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.