Warner Brothers: The Last Battle of the Streaming Wars?

A Personal View

It is the end of December 2025, and those who take an interest in such things are trying to come to terms with the significance of Warner Brothers agreeing to sell their production and streaming business to Netflix. The sale includes Warner Brothers' film and television studios, their film and television libraries, the intellectual property rights they own, and HBO and HBO Max. It does not include CNN and TNT.

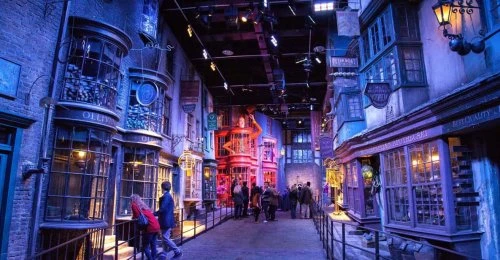

To understand how huge a deal this is, it is necessary to look at history. There is no greater name than Warner Brothers in the story of Hollywood. They were one of the greatest studios, perhaps the greatest, of the Golden Age, producing such classics as The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. Since there is no other way from the top but down, they fell into a decline following the end of the old studio system: like nearly all the other major studios they went through a series of takeovers and mergers, culminating in the establishment of AOL Time Warner around the turn of the Millennium. This multimedia conglomerate was widely to expected to dominate the entertainment industry in the 21st Century. It turned out to be a disaster, too big to innovate. Make a note of that: it will be important. Following the resultant break up, Warner Brothers still remained one of the remaining major studios. They made some shrewd purchases of "intellectual properties," most notably the film rights to the Harry Potter books and DC Comics. This enabled them to re-establish themselves as a major player, but in recent years they have been going too much down the Disney route and their management of potentially very lucrative franchises is widely considered to have been poor.

Netflix, by contrast, was founded only recently as a video rental company. When its original business model, sending out discs by post, was overtaken almost immediately by predictable technological advances, it became something of a joke. In order to survive it had to pivot dramatically, turning itself into a streaming service just as the technology was beginning to make such a thing viable. Its success, thanks to some daring purchases of the streaming rights of expensive films, and television shows such as Breaking Bad, was astonishing, but its real dominance began when it began investing in the direct production of its own content, starting with the initially masterful American remake of House of Cards.

Their success led many of the old media companies, including Warner Brothers, to enter the streaming market for themselves. So began the "Streaming Wars." It soon became obvious that, among many aspirants, there were only three serious contenders: Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney Plus.

Netflix had the advantage of being first in the field and thus, to a certain extent, shaping the battle. However, Disney and Amazon had two advantages Netflix lacked. The first was "synergy" with a broader range of corporate interests: Disney is not only selling you the film but the cuddly toy and the film experience at one of their theme parks; Amazon is also selling you the book of the film, the soundtrack, and the hard copy DVD if that is something that interests you, through its online shopping, where its real profit is made. More importantly, both Disney Plus and Amazon Prime support their offers of the latest "must see" content with huge back catalogues of classic films and television, Disney having their own and Amazon having purchased the film library of MGM, Warner Brothers' greatest rival during the Hollywood Golden Age. Netflix had nothing similar - until now, that is.

Most of the debate about the proposed merger has centred on its possible impact on cinematic production, but the future is in streaming and here there is no doubt that Netflix buying Warner Brothers is a very smart move. It will, among other things, fill the hole Netflix have always had in their offer relative to Amazon and Disney by providing them with that huge back catalogue in the form of the Warner Brothers film and television library. It will give them direct production facilities in the form of the famous Warner Brothers studios, should they want to use them. It will give them control of franchises including DC, Harry Potter, and Game of Thrones. This will give them not only be possibility of yet more exclusive premium content for their library but also the potential for future production in these franchises. It will offer Netflix subscribers more content for their money and more ways for Netflix to extract that money.

This is why Netflix probably paid over the odds for it, and why Warner Brothers were so quick to grab the deal. It is a win-win for both parties - but is it a win for the viewer?

Here a bit more context is necessary. This is a very crude summary of some complicated corporate manoeuvres. Having rich assets but underperforming, Warner Brothers had long been vulnerable to takeover. Their great rival, Paramount Skydance, made the first offer, which was rejected. As their name suggests, Paramount Skydance, own among many other assets, Paramount, another of the big Golden Age Hollywood studios. Comcast were also interested. Comcast is a very broad based conglomerate, and a relatively minor province of their vast corporate Empire is Universal, yet another big Golden Age studio. There are currently five major Hollywood studios still operating, Disney, Warner Brothers, Universal, Paramount, and Sony, two of which, Universal and Paramount, may be merged with a third, Warner Brothers, while a fourth, Disney, has a major streaming service in direct competition with Warner Brothers, who own HBO. Not so long ago the potential for building up a monopolistic trust in these circumstances would have the regulators stepping in, but such is the weakened state of Hollywood that things are being considered which would have been off limits before simply in order to keep "the Industry" going.

Only a few weeks ago the corporate politicking to take over Warner Brothers, or at the least part of Warner Brothers that gets most attention, was seen by most informed commentators as a duel between Paramount Skydance and Comcast, with the former as an overeager suitor and the latter as a potential "White Knight." The suggestion that Netflix might be interested was not taken seriously at first.

So the deal with Netflix came as a bit of a shock. Paramount Skydance have not taken it well, countering with a hostile offer to take over the whole of Warner Brothers, lock, stock, and barrel.

This is unlikely to succeed, but Paramount Skydance have a stronger card up their sleeve. The Netflix deal is very unpopular on both sides of the political spectrum. The other big studios and streaming services will doubtless join Paramount Skydance in lobbying hard against it. The Trump Administration has in general adopted a liberal attitude to regulation in the sense of a light touch. However, Paramount Skydance is dominated by the Ellison family, who are politically close to President Trump. The President's initial casual remarks about the deal have so far been negative, but that does not necessarily represent the Administration's final position.

One can understand why the deal is so widely unpopular. It is inherently monopolistic. Netflix seems to have won the "Streaming Wars," and if this deal goes through it will confirm their victory. Netflix will become the only streaming service that matters, the one to which anyone with any interest in keeping up to date with modern culture will have to subscribe.

Amazon Prime and Disney Plus will probably survive because of that synergy with their parent companies' other operations. So might some of the smaller streaming services if they can carve out their own niche markets. However, even the possibility of serious competition with Netflix will be gone.

As far as mainstream entertainment is concerned, Netflix will become practically compulsory. This might at first seem attractive from the point of view of the customer currently struggling to find the money to pay several subscriptions. Yet there are good reasons why my monopolies are generally considered to be unhealthy and governments usually try to regulate them.

Above all, they become lazy and inefficient in the absence of competition. Prices get higher, quality declines, the customer gets a worse service all round.

There is also the question of diversity, not only diversity in the sense of membership of specific demographics, but diversity of ideas, values, and tastes. This problem can only be exacerbated by the establishment of an effective monopoly by Netflix or anyone else.

From this lack of diversity of ideas will come a lack of originality and innovation. This is already apparent in the over exploitation of existing franchises. Ten years ago, Netflix, while they were still finding their way, were willing to experiment a bit. Now they seek more rigidly to the formula. Remember AOL Time Warner a few paragraphs ago? If you do, you have a better memory than some of today's top media executives.

Even the superficially attractive aspect of a monopoly, the possibility of paying a single subscription to view practically anything - the customer's ideal - itself demands qualification. One can expect the other surviving streaming services to remain just as jealous of their exclusive content as they are at present and Netflix will not be eager to share theirs either. So if there is anything specific you really, really want to see, you will still probably to have to pay another specific subscription.

Of less concern to the customer is what will happen to the people currently employed by Warner Brothers - not the overpaid executives who probably deserve what they are going to get, but the ordinary working people who lay the cables, build the sets, and make the costumes and props. On a biased personal note, I have happy memories of visiting Warner Brothers some years ago when it was very much a working studio, not a tourist attraction like Universal on the other side of the ridge. Most of the hospitable people I met back then are probably retired now, but I cannot help thinking of those like them who are still there. Netflix have coped so far without the overhead of such a large production complex of their own in Hollywood itself, not least because they have subcontracted to places like Warner Brothers. They might decide they want to remain agile and not tie capital up in expensive LA real estate. That would be the end of an important piece of American heritage in addition to making many ordinary people unemployed in an already harsh local economy.

This links to a broader issue. For some time now actual production has been leaving Hollywood because it has become too expensive and overregulated there. One might say that Hollywood, and Los Angeles and California in general, have only themselves to blame, and there is a lot of truth in that, but something unique will be lost when the American entertainment industry no longer has its globally recognised hub.

One way or the other, the Netflix deal will accelerate the process.

There is still a lot of uncertainty whether it will happen. Paramount Skydance might succeed in their hostile takeover or the regulators might step in to stop the whole deal or any number of things as unlikely as the Netflix deal itself looked a few weeks ago.

Of course in an ideal world, a great leader would step in and order a wholesale review of intellectual property law, making it easier to view content across different platforms, which is what most customers would prefer. This is obviously the one thing that is definitely not going to happen. Vested interests are too strong.

If forced to bet, I suspect that whoever finally gets Warner Brothers, or at least its studio and streaming elements, will be forced, either by the regulators or the markets, to sell off at least part. If it is Netflix, the regulators must surely, if they are doing their jobs at all, insist on HBO being sold off separately. If it is Paramount Skydance or Comcast, it seems unlikely that either of them would be allowed to retain two studios, so they might be forced to sell off one. Whether the one that was sold off could survive in its own in the current environment seems questionable to put it mildly. It therefore seems likely that the five remaining major studios will become four.

One thing, and one thing only, I will predict: there is likely to be a lot of work for some very expensive specialist corporate and entertainment attorneys over the next few weeks and months. They are the only ones doing well out of the mess Hollywood has made for itself.

Other Related Articles by John Winterson Richards

Is This the Golden Age of Television? (October 2022)

The Rise and Fall of the Female Action Hero (January 2023)

Reviewing the Reviewers (January 2023)

Why Television Matters (June 2023)

Heroes and Happy Endings - and Why We Need Them (January 2024)

Published on December 31st, 2025. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.