Ten Shows That Changed Television

A Personal View

History likes to simplify things. Great developments and discoveries therefore tend to be put down to a particular event or individual when, in reality, most - not all but most - are the product of many small steps by many people, and usually some false starts and unnoticed attempts before the high profile effort everyone remembers.

So it is with television. There are some shows remembered as "game changers" which might indeed to be wholly innovative but which may also be the only one in a long chain of similar experiments that enjoyed sufficient commercial success to make an impact.

Either way, there are moments when television was changed, when something was not only done but done so successfully that everyone in the Industry had to take it into account in their own subsequent decision making.

This article is not about format or technical changes, but about artistic choices, especially in the writing of scripted shows, that influenced the whole culture of television, and sometimes the general culture of their times.

Note that this is an Anglocentric list, written from the point of view of a British television viewer. The innovation and influence of non-English speaking shows on the development of global television is not addressed here specifically, but is acknowledged gratefully. A second list could easily be made of foreign language shows that changed British and American television.

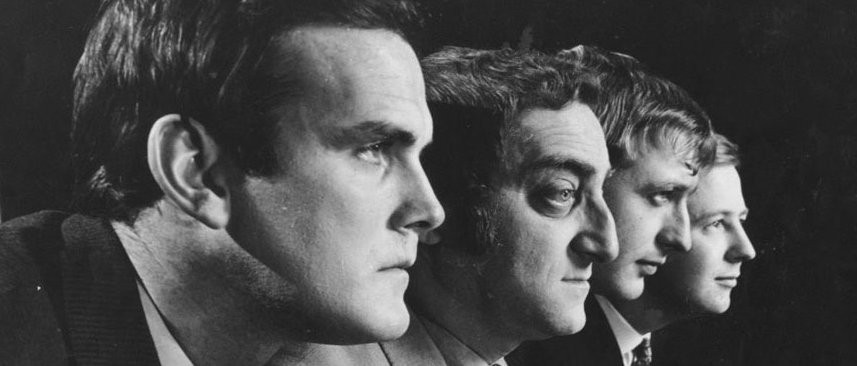

It is possible that no show changed both British television and British culture in general more than the satirical review 'That Was The Week That Was.' Overnight, television went from being excessively deferential to all forms of authority to being positively disrespectful, and most of Britain followed. The Satire Boom had arrived in the mainstream.

It is perhaps difficult to convey these days how shocking it was to have youngsters mocking the revered Wartime generation - the Conservative Government of Harold Macmillan, who had himself fought in the Trenches in the First World War, included three men who had risen to the rank of Brigadier in the Second. However, it was one of those three, John Profumo, who gave the satirists all the pretext they needed. Even by today's standards, 'That Was the Week That Was' showed no mercy.

Macmillan himself seems to have been very tolerant of the show, or at least the old fox was shrewd enough to understand the "Streisand Effect" long before there was a name for it and realised that it was politically safer to be seen to be going along with the joke in good humour than making futile complaints or attempts to suppress it.

The more sensible public figures have followed his example ever since.

2. The Avengers

If 'That Was the Week That Was' changed British culture by mocking the stuffy, self important Post-War, Post-Imperial consensus to death, 'The Avengers' took that process a stage further by putting an entirely new culture in its place.

It was 'The Avengers' that provided us with the image of the "Swinging Sixties" we still have today. Music and cinema also played their part, but it was television that brought the visual style that was initially associated only with a few trendy people in London into millions of British homes.

More importantly, it was 'The Avengers' that began to look at women in a new way. Cathy Gale (Honor Blackman) and Emma Peel (Diana Rigg) were not helpless virgins waiting to be rescued, nor were they were sex objects. They were fully drawn human beings with their own perspectives who were more than capable of looking after themselves.

As with 'That Was the Week That Was,' the main impact of 'The Avengers' was on British culture as a whole - and to an extent global culture because it sold well overseas - but it also changed television itself, both in its portrayal of women and in its demonstration of the power of the medium as an instrument of fashion.

3. Star Trek

The full significance of 'Star Trek' only really became apparent some years after its cancellation. It cannot be emphasised enough that, when it was first broadcast, 'Star Trek' was just another piece of schedule filler. It is only in retrospect that we see it marked the beginning of "cult television" - the notion that a show can have an impact on the lives of at least some of its viewers far in excess of ephemeral entertainment.

The show's ratings on network television were poor and its cancellation was postponed only by a letter writing campaign by fans. This happened to coincide with a growing sophistication on the commercial side of television, with the raw viewing figures being broken down into market segments, and it seems that the network and advertisers were impressed by the quality of some of the notepaper they received, indicating market segments with high potential spending power.

There really was nowhere for this new understanding to go when broadcasting in the States was still dominated by the Big Three networks. However, the subsequent growth in the commercial power of syndication - where repeats of 'Star Trek' were a great success - and a general increase in the number of channels eventually broke the monopoly of the old networks as the minor players began to commission and produce shows of their own. This multiplicity allowed the development of material particularly for specific segments, including what was more deliberately "cult television."

A number of satirical reviews followed in the footsteps of 'That Was the Week That Was,' some involving people who had contributed to it. Most avoided its emphasis on current affairs. Indeed, political satire had to wait until 'Not the Nine O'Clock News' for a successful revival on British comedy.

Until then, most of the satire was more social than political. Much of it was written and performed by young Oxbridge graduates who went from one fairly short lived show to another before coalescing in two distinct groups, who were to become known as the Pythons and the Goodies. There was nothing inevitable about this. It was just how the criss crossing ended up.

What made 'Monty Python's Flying Circus' distinct from the sketch shows that preceded it was its successful embrace of the surreal. The nonsensical title, the theme music, and the Terry Gilliam cartoons were a declaration that it was determined to be different. It was the Beatles' 'Sergeant Pepper' aesthetic on weekly television.

Few shows followed its extreme embrace of the surreal, a fashion which was in any case as dead as a Norwegian Blue well before the end of the Seventies. Its real legacy was demonstrating to producers, especially of television, that there were no limits to the artistic expression of which television was capable.

5. MASH

For many years, British television looked down on its American counterpart. American drama and comedy were commercially successful because they were slick, well packaged, and run to tried and tested formulae - the very reasons the British cultural Establishment looked down on them.

It was when they saw 'MASH' that snobby Brits began to wonder if the brash Americans might after all be capable of producing works of genuine artistic merit.

Its great innovation was its blending of comedy with drama. Although nominally about jolly japes in the emotionally distant Korean War, everyone knew it was really about the then deadly serious and topical subject of Vietnam. The way in which a much loved major character left the show remains one of the most shocking moments in the history of any genre.

Indeed, British viewers probably appreciated this aspect of the show better than American, because the initial British broadcast did not use the intensely annoying laughter track with which it was shown in the States. While not entirely a prophet without honour in its own land, 'MASH' was therefore better understood and enjoyed abroad than it was by the people at whom it was aimed and to whom it was most relevant.

If 'MASH' leavened its comedy with tragedy, 'Hill Street Blues' moved towards a similar synthesis from the other direction by lacing its drama with humour.

It was just one of several innovations in a show that was truly revolutionary. Indeed, if this was much shorter list and it was necessary to nominate 'One Show That Changed Television Drama,' that show would be 'Hill Street Blues.'

The "cop show" had previously been run according to some of the most reliable and predictable of those American formulae. There was a clearly delineated hero - whose name was usually in the title, like Ironside or Cannon or Kojak or Rockford - who could be relied upon to wrap up the Case of the Week within the hour, advertisements included.

In 'Hill Street Blues,' writer-producer Steven Bocho seemed determined to tear the rule book into tiny pieces. The lone hero and his mystery became a large cast playing flawed, morally complex protagonists in a multistrand storyline, and the weekly free standing episode became gave way to long character and story arcs.

This has since become so much the new normal that it is now difficult to convey or remember how radical this was at the time. Television drama can really be dated Before or After Hill Street.

If the original 'Star Trek' was, in commercial terms, ahead of its time, 'Star Trek: the Next Generation' helped to define its time, building a whole new business model for television drama.

It took off where the original had left off in developing the idea of "cult television," except that it did so quite deliberately, and then it went a stage further by developing the idea of "the franchise."

This was not a new idea. Other shows, including the likes of 'Thunderbirds' and, of course, the original 'Star Trek' itself, had diversified into films, toys, games, books, comics, and so on. What made 'Star Trek: the Next Generation' different was how this diversification was central from the start.

The key to the strategy was presenting the audience with a fully realised and textured television universe. Previously, the setting had been background to the plot, like a scene that could be shifted at need as the story required. In 'Star Trek: the Next Generation,' a wholly fictional future universe became a character in its own right.

As a result, fans bought technical manuals for a Star Fleet that did not exist and phrase books for a Klingon language that did not exist either. If George Lucas has taught us nothing else it is that licensing is where the real money is, and no television franchise has been as financially successful as 'Star Trek' by following his example.

Cheap, cheerful, and, to be honest, of variable quality, 'Xena Warrior Princess' was hugely influential in two ways.

First, it marked the next major step in the portrayal of women on television. The cinema had been comfortable with women in the leading roles of action films since Sigourney Weaver's Ripley in 'Alien,' but there was a real question mark over whether a woman could carry the lead in an ongoing television series that would also attract male viewers. Earlier attempts at action shows with a female protagonist had not been very successful. Xena settled the matter once and for all, and opened the floodgates to a tide of similar women warriors, some a lot more credible than others, who have become almost compulsory in action shows ever since.

Second, it was the first show that became a success due in large part to the internet. Released in syndication in the United States, and on minor channels in overseas markets including the UK, it was not watched by that many people, but those who did watch it tended to write about it online, in everything from scholarly articles to dubious "fan fiction," so that everyone knew the name even if they had not seen it. The sensible decision was made to hold the intellectual property rights on a fairly loose rein, giving the fans themselves a real sense of ownership - in a legally non binding sense, of course.

9. The Sopranos

Where 'Hill Street Blues' gave its protagonists moral complexity, 'The Sopranos' ended that complexity by making them downright rotten - while still retaining the viewers' sympathy.

This amazing contradiction was pulled off by making the characters multi dimensional. We came to care about them even if we did not not like them. We could still see parts of ourselves in them even if we hoped we were not them. We saw their vulnerabilities and they were the same ones we sometimes saw in ourselves. Above all, we saw their sense of humour, which made it a guilty pleasure to hang out with Tony and the Guys ...at a safe distance, the television screen performing much the same function as the reinforced glass in a shark tank.

It gave us that wonderful thrill of feeling close to danger without really being at risk.

As a result, it is now almost as common for the protagonist in a television drama to be an anti-hero as a hero, even a flawed one.

10. The Wire

While 'Hill Street Blues' and 'The Sopranos' brought a new realism to character, story remained a matter of careful structure. The great contribution of 'The Wire' was to extend that realism to plotting.

Based on a pair of meticulously researched and observed non-fiction books, 'The Wire' sometimes plays out like a dramatised lecture on urban sociology. Events happen not out of dramatic necessity but because they just do. Major characters die ridiculous deaths rather than acting out their tragic doom. Life is like that.

It is sometimes like watching a documentary, but without the intrusion of the documentary style and with the dark humour that made even the characters of 'The Sopranos' so engaging. As a result, the viewer finds himself completely immersed in a different world, not necessarily a pleasant one but certainly a fascinating one.

Its dramatic power is increased by the knowledge that these sort of things might actually happen and actually have done.

It is difficult to see where scripted television can progress from here. Indeed, 'The Wire' may since have been equalled but it has not been surpassed.

The multiplicity of channels now offers a huge range of shows, covering all sorts of niches and "cults." Many of those shows are of a much higher level of sophistication than even the revered classics of the past. Television comedy and drama have both changed fundamentally over the last sixty years.

The old formulae are dead. New formulae have taken their place. Much has improved, but much that was of value has been lost, not least a certain innocence. Only one thing is certain: change will come, like it or not.

Published on October 28th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.