Ten Ways to Ruin a Good Show

A Personal View

by John Winterson Richards

It is surprisingly easy to learn how to write a television show. Whether it is a good one or not is, of course, another matter altogether, but the technical side is no longer a trade secret. There are a lot of good courses and books out there on how to do it.

The best are often on how not to do it. They provide a check list of basic mistakes to avoid. Then, once the script is complete, the writer should go through it ruthlessly, comparing it with that list and taking out anything that might look remotely as if it might be on it. This brutal self editing is what separates professional writers from amateurs.

Yet even the very best writers, successful and super-talented "showrunners," make avoidable errors that spoil their own masterpieces. This is a check list dedicated to them.

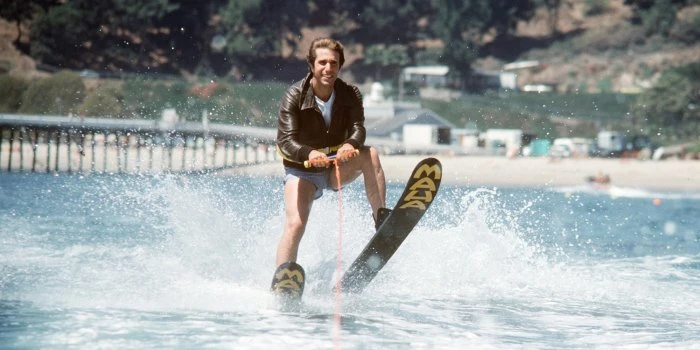

1. Jumping the Shark

It is generally agreed that the moment which confirmed that the much loved Happy Days' really had gone on too long was the the episode in which the Fonz (Henry Winkler) rather pointlessly did a water ski jump over a shark. Ever since, "jumping the shark" has been Industry slang for running out of ideas.

That is perhaps unfair to the shark - and indeed to the writers. The real sin of "jumping the shark" is actually the going on too long. A truly successful show should follow the example of Fawlty Towersand quit while it is ahead. Of course, the reality is that most producers would rather squeeze as much as they can out of a cash cow while it lasts. There are exceptions, but artistic integrity can be very expensive.

2. Character Dependency

The Fonz is also the classic example of another common error: allowing a popular character to become too dominant. Of course many shows are meant to be led by a particular character, but when a supporting character becomes the "breakout character," or one of the principals becomes too powerful in what is supposed to be an ensemble cast, the charm of the character diminishes through overuse and the whole show becomes unbalanced.

The latter phenomenon can be seen in M*A*S*H, as Alan Alda became more prominent both onscreen and behind the scenes. To his credit, Alda seems to have been aware of the dangers and made some effort to treat his castmates with respect, but there were times when the later seasons seemed more like 'The Hawkeye Pierce Show.'

3. Insulting the Viewer

A successful show is one that encourages the audience to identify with the characters and invest emotionally in what happens. Having invited the viewers to do that, the show insults them when it suddenly says that none of what has gone before really matters.

This tends to occur when the show has written itself into a corner, and lazy writers collapse the whole reality they have established over time. The most infamous example is surely when Bobby stepped out of the shower in Dallas and Pam claimed the whole previous season was just a dream. Although it managed to stagger on for a while afterwards, and later in a "reboot," the show really died at that moment.

4. Time Leaps

This is another reset button for lazy writers. When they feel they have left themselves nowhere else to go, they leap forward a few years and put the characters in a completely different situation. This is was the beginning of the end of Desperate Housewives and the final torpedo into Xena Warrior Princess.

In his famous 'Poetics,' the original handbook for sciptwriting, Aristotle wrote of the three essential unities - of time, place, and action. To be honest, it is a rule much honoured in the breach, and modern television writers love to play with it. Yet the fact remains that people are accustomed to a straight narrative and a drama that jumps all over the place can lose their attention very easily.

5. The Overly Dramatic Twist

The Dramatic Twist is a very effective storytelling device. It requires total surprise, but it works best when the viewer can almost immediately look back and see that there were hints of it all along - "foreshadowing."

It does not work at all if it is arbitrary and contradicts all that has gone before. Then it reveals itself for what it is, a twist for the sake of a twist. It becomes positively annoying when it negates all the previous character development in which the viewer has invested. The 'Principal and the Pauper' episode, in which a major character's whole backstory was destroyed, is arguably the moment when 'The Simpsons' really '"jumped the shark" - see above - but then 'The Simpsons' has jumped the shark so often that it could enter the Olympics if ever shark jumping becomes a competitive sport.

6. To Its Own Self Being Untrue

The same destruction of a character's previous development was seen time after time in the last seasons of Game of Thrones- Daenerys, Tyrion, Jaime, Cersei, Varys, Baelish, etc. Yet they were just symptoms of a much deeper problem in that show: the characters got stupid because the show got stupid.

That was particularly disastrous for a show that had traded on its intellectual subtlety, making the previously disreputable fantasy genre respectable through its mastery of political and social nuance. Intelligent viewers who were lured into it by its game of human chess were repelled when it suddenly ended with a series of slam-bam contrived shock moments.

The showrunners appear to have been impatient to cut short the final seasons in order to get on with other projects. So they ditched most of the human drama that had made the show so compelling and rushed the ending. In the process, they threw away the greatest gift they will ever be given in their careers, and branded themselves forever as "The Guys Who Ruined Game of Thrones."

Yep, still angry about it...

7. Requited Love

Tension is good drama. That is especially true of unresolved sexual tension. However, once that tension is released, nothing remains but to doze off.

This is why unrequited love, or romantic love facing insurmountable obstacles, has been the basis of so many great stories, but they always stop at the "happy ever after." Few are interested in seeing a boringly normal family life, still less in seeing the practical difficulties of a marriage of people from different backgrounds after Cinderella lands her Prince. Most of us would rather be left with our happy illusions.

So Frasier really lost much of its appeal when Niles ran off with Daphne, ending the rather sweet subplot of a man hopelessly in love with a woman with whom he had very little in common. Their romance was always far less interesting than its apparent impossibility. There were other aspects of the show that kept it reasonably entertaining afterwards, but a lot of the heart went out of it at that point.

8. The Demographic Character

A single annoying character can ruin a whole show. Such a character can be doubly annoying when he is obviously there to serve a certain demographic. The producers of Star Trek: the Next Generation were obviously correct in their assumption that teenage males were a key target market for their product, but dead wrong in their assumption that putting one on the bridge of the Flagship of Star Fleet would attract them. No one identified with Wesley Crusher, who was sidelined as soon as it was decent to do so.

It can also be irritating when a character from a fashionable minority seems to be there to serve a political agenda rather than dramatic necessity. Such characters - always basically noble and rather two dimensional - add nothing to the plot and tend to stick out for what they are. The suspicion of tokenism in a production tends to undermine other characters from minorities who may be more dramatically interesting in their own right. However, it must also be said that there are occasions when good writing or acting or both raise what seems at first a tokenistic minority character to another level entirely as an obscure young actor called Denzel Washington did in 'St Elsewhere.'

9. Shouting the Message

There is nothing wrong with politically committed drama - even if it is wearing that it seems to come almost exclusively from just the one side of the political spectrum. Some of the best writing is the product of burning passion.

The problem arises when that passion takes the form of beating the viewer over the head with "The Message." The best political dramas are subtle, inviting the viewer to look at issues from different points of view and identify with different characters. Indeed, the very best may not appear to be political at all. The likes of Xena Warrior Princess and Buffy the Vampire Slayer were far more influential in changing attitudes to the role of women in the modern world than any explicitly feminist tract that would have been watched only by other feminists.

By contrast, The West Wingwore its politics on its sleeve, and was much lauded - mainly by those who shared its viewpoint - but is unlikely to have made many converts. Its portrayal of an idealised Democratic Administration coincided with the election and re-election of George W Bush.

10. Inauthenticity

The best television drama, and to a lesser extent comedy, has to feel real. The more the viewers can let go of their actual reality for a while and immerse themselves in the artificial reality presented by a television programme, the greater its impact will be.

So contemporary shows obviously ought to be as realistic as possible, and even fantasy, horror, and science fiction are most effective when their non-fantastic elements feel authentic so that the fantastic elements have greater credibility when they occur - this was one of the great strengths of 'Game of Thrones' back in the glory days.

Historical dramas, and contemporary shows based more or less on real events, are also well advised to stick as closely as possible to their source material. This does not necessarily mean the most reliable source material - I, Claudius, arguably the greatest historical drama of them all, relied a great deal on the gossipy Roman historian Suetonius Tranquillus, of whom the original novelist Robert Graves was a scholarly translator for Penguin Classics but who is not rated so highly by mainstream academia. The point is that there is a definite authenticity in the original voices, even the less prestigious ones, that comes across in a good adaptation.

The immersive experience of the viewers is enhanced by the knowledge that what they are seeing is real - or at least might have been real. There is also the bonus that real life usually offers better stories than even the most imaginative writers. Truth really is stranger than fiction - and indeed often has to be toned down in case it seems too incredible.

It is no coincidence that in the Golden Age of British Historical Drama, from the late 1960s through the 1970s, the likes of The Caesars, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Elizabeth R, Napoleon and Love, Fall of Eagles , and 'Prince Regent' showed great respect for their primary sources. They used great dramatic licence in filling in the gaps where those sources are silent, but were careful not be positively anti-historical.

Sadly the same cannot be said of more recent projects like 'The Tudors' and 'Versailles.' In trying to be more "modern" they lost sight of what makes history so fascinating as a genre. They would have been more successful dramatically had they stuck closer to the facts.

These are only the top ten mistakes made by successful writers and producers. There are many others. The list could go on ...and on - and, of course, the list of mistakes made by the unsuccessful is longer still. These mistakes did not stop any of the shows mentioned being commercial and critical triumphs. Greatness is still greatness even when it falls short of perfection. Perhaps the point is that even the greatest will always fall short of perfection - or that excellence is, by definition, not attainable consistently. Or perhaps, with television shows as with diamonds, their flaws and imperfections are part of what makes them interesting.

Published on October 16th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.