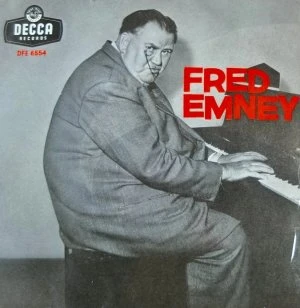

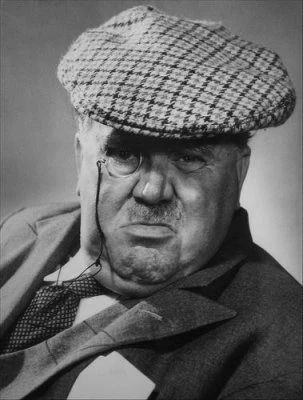

Fred Emney

The Monocled Master of Mirth.

The 20-stone master comic of the monocle, cigar and pompous manner, was a show-business veteran with more than 60 years in the world of entertainment to his credit.

Fred Emney was born into the world of show business. His father, also named Fred Emney—the "original," as one might say—was a popular figure in musical comedy, his reputation standing alongside music hall legends such as Little Tich, Harry Tate, and George Robey. One of his most celebrated routines, A Sister to Assist ’Er, was performed with actress Sydney Farebrother continuously for more than three years on stages across the country, and several other sketches enjoyed similar success. In 1894, he met Blanche Round, who was appearing on the same pantomime bill in a modestly received act called the Sisters Doris. A year later, the two were married.

The Emneys made their home in New Malden, Surrey, after Blanche left the stage to raise their growing family. Their first child, Doris, was followed by another daughter, Blanche (aka Coo), then young Fred, and later Joan and Dennis. From an early age, Fred adored his father and seized every chance to watch him at work in the theatre. Tall but not yet the portly figure he would later become, Fred quickly resolved that his future lay on the stage as well. He learned the piano and began composing his own melodies, though his father—mindful of the precarious nature of show business—was reluctant to encourage him, preferring that he secure a solid education.

Fred’s schooling began at Cranleigh in 1908, but when his father heard that Cliftonville offered better prospects, he transferred him there. The move proved unsuccessful, and Fred soon returned to Cranleigh to complete his studies. By then, however, his mind was firmly set: the only education he truly wanted was in the theatre. In 1915, he left school and auditioned for a role in the play Romance. When he was accepted, his father’s pride was unmistakable.

Fred’s role in Romance proved short-lived. At fifteen, and shooting up in height, he was cast as a pageboy but quickly began to outgrow his costume. When he asked the producer for a new suit, the response was blunt: it was cheaper to replace the boy than the outfit. Fred was promptly dismissed.

Undeterred, he auditioned the following summer, for a production at Drury Lane—The Best of Luck—and was engaged at two guineas a week. His role was that of a “silly ass,” complete with oversized cigar and monocle, a comic persona that would become his lifelong trademark. The performance was such a hit that the producer offered him a part in the forthcoming pantomime, Puss In Boots, at the handsome rate of fifteen pounds, with half-salary for matinees. Yet as rehearsals progressed, his role was steadily whittled down until it disappeared altogether. Though he continued to draw his wages, Fred found little satisfaction in being paid for doing nothing.

The following year, while watching his father perform, young Fred witnessed a tragedy. Fred senior slipped and fell during his entrance. Though he managed to struggle to his feet and finish the performance, he collapsed afterwards and was rushed to hospital. His internal injuries were severe, and despite two operations he could not be saved. He died on 7 January 1917.

With the First World War still raging, Fred enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps, although not as a pilot. It proved to be an unhappy chapter. At seventeen, he was still shooting up in height—already over six feet tall but weighing less than ten stone. His frail health soon gave way, and a doctor placed him on indefinite sick leave. Nursed back to strength by his mother, Fred later wrote to his camp to report his recovery and willingness to return to service, but no reply ever came.

By 1919, restored to full health, Fred resolved to return to the stage. His father had earned well during his career, but he had also spent freely. The children had enjoyed the best education money could buy, the Malden home had always been fully staffed, and Fred senior gave generously to charities and lent liberally to fellow performers—loans that were rarely repaid. Enough was left to provide for his widow, but his children were expected to make their own way.

Ambitious and eager for new horizons, Fred set his sights on America.

With little money to his name, Fred secured free passage to Canada aboard a cargo ship owned by his uncle, and carried with him a letter of introduction from Fred Karno to Charlie Chaplin. His journey took him first to Nova Scotia, then on to Quebec and Montreal, before he finally boarded a train bound for New York. By the time he reached the United States, the modest twenty pounds he had left England with were gone. Fortunately, his mother had arranged to cable him two hundred dollars upon his eventual arrival in Los Angeles. Once there, Fred checked into an expensive hotel which was known to be one of Chaplin’s favourite haunts—a decision that quickly proved worthwhile.

Presenting Chaplin with Karno’s letter, Fred was warmly received. Chaplin, delighted to meet the son of the famed Fred senior, whisked him off to a nightclub and assured him he would help launch his career in the movies. He instructed Fred to report to his studio the next morning.

Eagerly, Fred arrived at the studio gates, only to be turned away by the guard, who dismissed the nineteen-year-old Englishman. Fred protested until Chaplin’s manager was summoned, but he too refused him entry.

That evening, Fred encountered Chaplin again at the hotel and explained his predicament. “Oh, what nonsense!” Chaplin exclaimed. “Come tomorrow morning and ask for me personally—I’ll see to it.” Encouraged, Fred returned to the studio the next day, but once again the manager barred his way.

Disheartened and accepting that Chaplin’s promise would not materialize, Fred began seeking work at other studios in any capacity. Yet opportunities were scarce, and his funds were dwindling fast. He packed up his suitcase and left Hollywood and got on a street car to the end of the line. He arrived in San Fernando with less than a dollar in his pocket.

Desperate for work and willing to try anything, Fred crossed paths with a fight promoter who gave him a long, appraising look. Noting his tall, muscular frame, the man asked if he’d ever boxed. “I did,” Fred replied exaggeratingly. “Plenty, back in the Royal Flying Corps.” Pressed on whether he was any good, Fred stretched the truth even further: “Never lost a fight.”

That was enough. A bout was arranged for that very night, with the promise of forty dollars—and the prospect of more if he proved himself. But once in the ring, Fred’s bravado crumbled. He was battered mercilessly, lasting four punishing rounds before the truth of his inexperience was laid bare.

With fresh funds cabled from his mother, Fred made his way to San Francisco and checked into a holiday camp with an acquaintance he had recently met. The camp was a makeshift community of tents and marquees, complete with a grocery store and a small wooden post office.

On his very first night, Fred was jolted awake by the acrid smell of smoke. Throwing open the flap of his shared tent, he was confronted by a terrifying sight—the camp was ablaze. Flames leapt wildly around him as he bolted to safety. Miraculously, no lives were lost, but by dawn the camp lay in ruins.

Returning to the city, Fred was suddenly intercepted by two police officers and taken to Santa Rosa police station without explanation. He was locked in a cell. It was the beginning of a four-week ordeal. The authorities accused him of setting the fire at the camp and looting the post office during the chaos. To make matters worse, his acquaintance gave a statement claiming he had “thought” he heard Fred leave the tent that night.

Charged whilst steadfastly denying both allegations, Fred was subjected to relentless interrogation—hour after hour, day after day—by a rotating cast of questioners determined to wring a confession from him. At last, he was assigned a lawyer, but any hope of relief quickly evaporated. The man clearly doubted his innocence and bluntly advised him to plead guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence of ten years as opposed to life, if found guilty at trial.

On the twenty-seventh day of his arrest in San Francisco, Fred was finally brought before a judge. The trial opened with a litany of supposed details about his movements on the night of the fire—fabrications so elaborate that Fred listened in stunned disbelief.

Then, in a startling turn which would not have been out of place in a fictional drama, the Chief of Police of Sonoma County entered the courtroom to halt proceedings. He explained to the judge that the authorities had only the night before uncovered the true cause of the blaze: an electrical fault. An amateur electrician had been experimenting with new equipment, and something had gone disastrously wrong. With this revelation, Fred was acquitted on the spot and released.

Yet the ordeal ended with one final indignity. Before the police would let him walk free, they demanded payment of thirty-seven dollars—the “rent” for his Santa Rosa cell during the weeks he had been unjustly imprisoned. Weary and eager to put an end to his nightmare, Fred paid the sum and left the whole wretched episode behind.

However, the San Francisco police hadn’t finished with Fred just yet. While visiting Oakland one afternoon, he was suddenly slammed against a wall by two officers and hauled off to the station. There, they thrust a photograph in front of him.

“That’s you, ain’t it, Spud?” one demanded.

Fred studied the picture. The face bore no resemblance to his own, yet the officers pressed him relentlessly to confess. For nearly an hour they insisted he was their man, until at last they checked his movements and discovered he couldn’t possibly be the suspect.

The real culprit was a man named Spud Murphy, wanted for shooting a sheriff and raping a young woman. His description happened to match Fred’s general appearance, even though the photograph they held on file of the wanted man was a ridiculously poor likeness. It was at this point that Fred, unsurprisingly, decided to leave San Francisco.

After another attempt to make his mark in Hollywood, Fred decided to return to Britain. What awaited him, however, was a bitter shock. His mother had lost much of the inheritance left by his father through a poor investment, and although his sisters were working, they were struggling to make ends meet. Fred rented a modest flat in Paddington and began the search for employment.

After the freedom and opportunities he had experienced in America, life in Britain felt stifling. Months passed before he finally secured a booking at the Holborn Empire, but his performance failed to win over the audience. Disheartened and restless once more, Fred abandoned the attempt to get back on the showbiz trail and set his sights back across the Atlantic—this time bound for Toronto.

Once there, Fred had the break he had been trying for. He set to work writing a Christmas pantomime for Shea’s Hippodrome, and the result was a resounding triumph. What was meant to run for just two weeks stretched into a nine-week sensation. Impressed, theatre owner Jack Arthur assured Fred that he would always have work whenever he needed it. It marked the beginning of six years of uninterrupted success. Furthermore, Fred had met a young lady, Hazel Wiles, and they quickly fell in love. They were married shortly after.

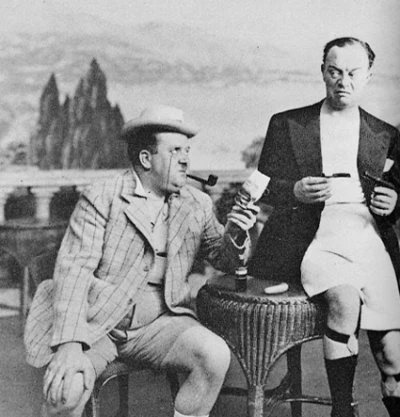

By now, Fred was the top earner in Canada, being paid three hundred and fifty dollars a week. It was during his fifth tour that Jack Benny saw one of Fred's shows. "You're crazy", he told Fred, “to stay with this lot. You're great stuff. Go to either London or New York. That's where the real money is and believe me, you can't fail." In the spring of 1930, Fred set sail once more for London.

On his return to Britain, Fred found that he was getting the same cold shouldered response from every agent he approached. The conversations went along the lines of, "What did you say your name was?"

"Fred Emney."

"But he's dead."

"That was my Father."

"He was a great comic."

"I know he was."

"Well...what do you do?"

"I'm a comedian."

"My dear fellow, we have enough comedians on our books to last twenty years. And good ones, too!"

This went on for months until Fred finally got a small spot in Blackpool as a second pianist on the Central Pier. It proved to be a fortunate booking. Although only the second pianist, Fred soon found that whilst seated at the piano, he was expected to fool around and gag as much as he liked whenever he thought it appropriate to do so. The show opened and was an immediate success. He formed a double-act with Victor Leopold, and they began getting bookings around the country, ending up in London.

One night they were visited by George Black and Val Parnell – who ran the Moss Empires. They told Fred that rather than doing a double act with another man he should be looking out for a beautiful, talented girl. If he got one, they’d be happy to find him bookings. As it turned out, it was the girl who found Fred. He name was Irene North, and she had sought out Fred because she wanted a song to perform if she got a job in pantomime, and she asked if he'd write one for her. Taken with Irene, Fred suggested the double-act idea. She delightfully accepted.

Irene had been playing in a concert party on Worthing Pier and convinced the management to let them have a try out as guest artistes. The manager stipulated that he would allow them a spot but not pay them for it, and they weren’t to stay on the stage for too long. That Saturday night, they brought the house down. The audience wouldn’t let them leave the stage (and the manager didn't want them to, either). The bookings began to roll in. They continued their act with great success until 1933, when Irene became ill and could not continue.

Alone again, Fred managed to secure the part of Lord Leatherhead in Mr. Whittington, at the London Hippodrome. Fred was hailed as a great success and went on to appear in another successful show, Seeing Stars. It was an apt title because many stars did come to see the show, including Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. On seeing Fred, Fairbanks wanted to launch him in films. But the producers of Seeing Stars refused to let Fred out of his contract.

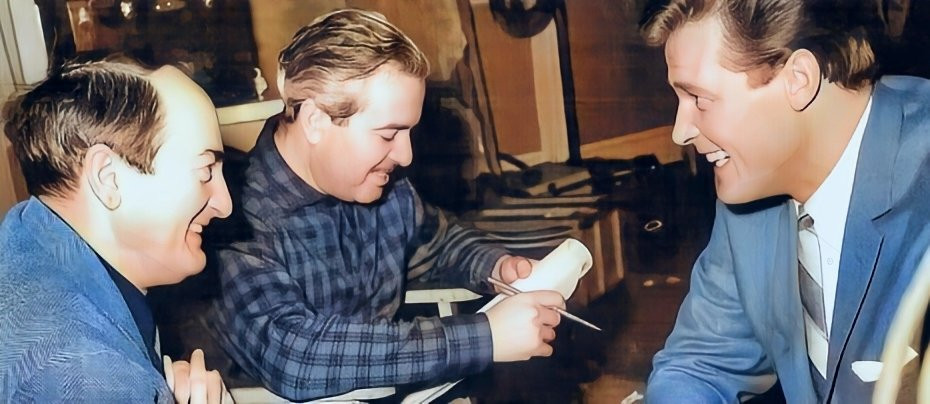

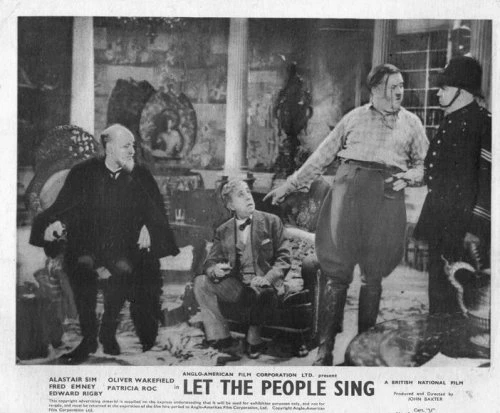

Having made an uncredited appearance in the 1932 film, A Man of Mayfair, Fred was eventually cast in Brewster’s Millions (1935) alongside his great lifelong friend Jack Buchanan. He made an early television appearance alongside Leslie Henson and Richard (Mr Pastry) Hearne on 14 May 1937 when Theatre Parade: Scenes from Swing Along were screened on the BBC live from the Gaiety Theatre. Fred and Buchanan formed a double-act of sorts, when war was declared in 1939. They took their show on tour to entertain the troops during that period referred to as ‘the phony war,’ the time before France was invaded and bombs began dropping on Britain. Eventually, the show, All Clear, returned to the UK where it toured for seven months at a number of theatres up and down the country. It was in Sheffield that Fred and the cast very nearly lost their lives.

Rehearsals for a new show Top Hat and Tails stretched late into the night when the wail of air-raid sirens cut through the theatre. Fred, along with Adele Dixon and Jack Buchanan, made their way back to their hotel. No sooner had they arrived than the entire building shuddered violently as bombs rained down in one of the fiercest attacks the city had endured. Fred had not yet reached his room, but when he opened the door he saw that it had taken the brunt of a blast. The window had been blown in and glass was scattered everywhere. Fred turned to leave as another bomb exploded nearby, knocking him off his feet. One of the cast, Mary Lawson was tragically killed along with her husband. It was only the following morning as first light streamed through the shattered windows, that Fred and Jack realised that the lounge they had sheltered in throughout the worst of the raid, had a glass roof.

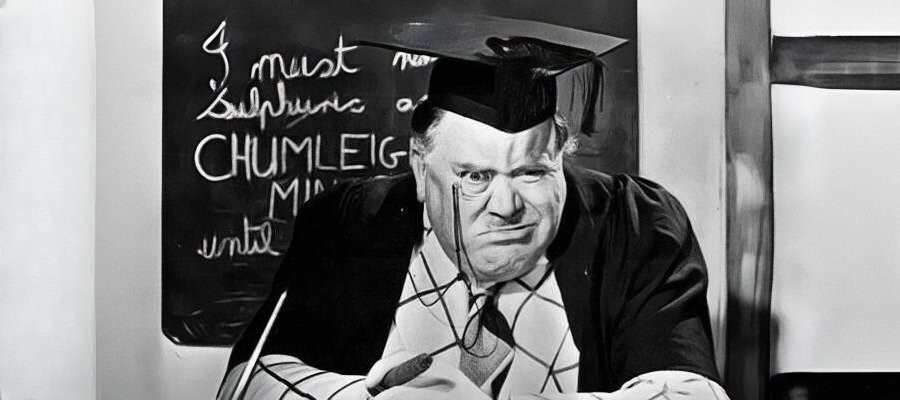

Fred continued to build his reputation throughout the 1940s and was given his own self-titled radio show on the BBC Home Service. Into the early 1950s he continued appearing on stage, receiving plaudits in Blue for a Boy, which again featured Richard Hearne in the cast. But it was Fred who won over the critics when they were ready to crucify the production. John Barber in the Daily Express wrote: 'as I was about to walk out, in walked Fred Emney. He saves the day, this gorgeous Jumbo-this walking Taj Mahal-this cigar smoking Easter Egg. See him dressed as an authoress in a pastel tea-gown. See him rumba with pretty Aud Johansen. But don't - if you can - look past or beyond him.'

In 1954, the BBC offered Fred an exclusive three-year contract and on 7 June, Emney Enterprises began on BBC television. Clifford Davies wrote in the Daily Mirror; ‘Fred Emney came over well in his own TV show, Emney Enterprises, last night. He fires off jokes like broadsides from a Centurion tank. In girth, of course, that’s just what he is, and he is shrewd enough to ensure his humour is to match. Emney Enterprises merits a series of regular appearances.’

The show did not return until October, as Fred—co-writing with Max Kester—was locked in negotiations over its style. The BBC initially pushed for a familiar slapstick formula, but Fred resisted. His brand of comedy, he argued, was subtler, cleverer, and always just the right side of the ridiculous.

In the meantime, a radio adaptation had been broadcast, and its success helped tip the balance. The BBC relented, granting Fred full freedom to shape his scripts. With performers such as Deryck Guyler, Kenneth Connor, and Charles Hawtrey, Emney Enterprises ran for three series between 1954 and 1957, growing stronger with each outing. When the series came to an end the BBC offered Fred another series. The Fred Emney Show only ran for four thirty-minute episodes, and at the end, Fred’s three-year BBC contract was up.

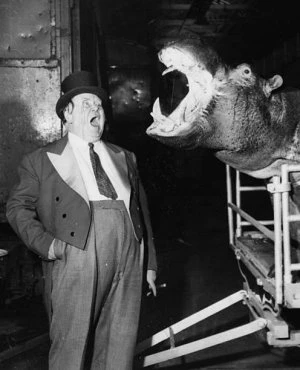

As Christmas 1958 approached, Fred received a very unexpected offer from Chipperfield’s Circus. The year before, Dick and John Chipperfield decided they’d like to try a Christmas season in Birmingham, which would help to pay the large weekly bill for the circus animals’ keep. It proved successful enough for them to try again in 58-59. But this time they wanted Fred to take part as the Ringmaster. They offered him a large amount of money, and with no TV series currently in the offing, he accepted. Again, it was a great success, although he ended up suing the Chipperfields after he fell from a caravan. Showing a judge a picture of the site, he pointed out: "That's me, my lord, and that's a hippopotamus."

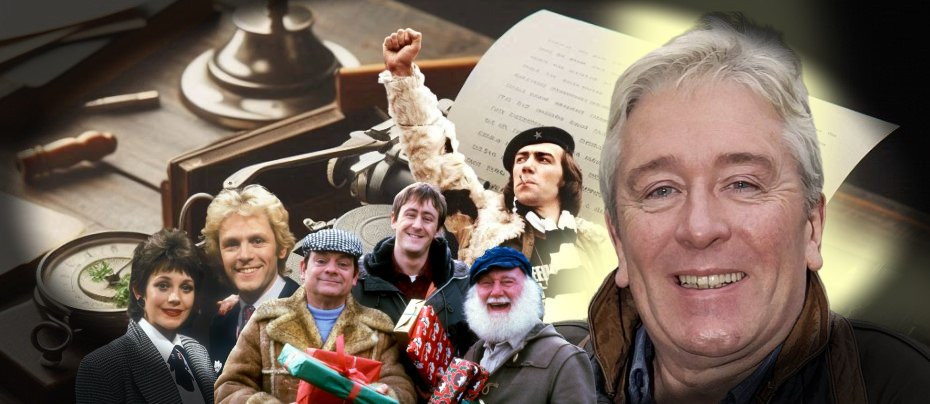

During the 1960s, Fred remained a familiar face on stage and screen. In 1963 he made the first of eleven appearances in the popular sitcom Hugh and I, playing the delightfully eccentric Lord Popham. Between 1967 and 1968, he took on a different role as the human foil to the mischievous puppet duo Pinky and Perky, and he also featured in several comedy films, including Father Came Too! and Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines.

By the 1970s, his career had begun to slow, and his appearances became increasingly rare. His final television role came in 1974, followed by parts in two risqué British comedies—The Amorous Milkman (1975) and Adventures of a Private Eye (1977). Yet amidst this winding down, Fred received one of the greatest honours of his career: in 1971, the Variety Club of Great Britain presented him with a special award celebrating his remarkable 55 years in the entertainment business.

Fred said of his talents: "I suppose I'm a comic because I haven't got enough brain to be anything else. I don't know why they laugh. I just come and say, 'Good Evening' and they laugh."

In his later years, Fred retired to Bognor Regis in Sussex. The comedian—who once quipped that he could not live without his daily cigar—was admitted to a local hospital on 23 December 1980. Two days later, on Christmas Day, he passed away at the age of 80. His wife, Hazel, survived him by only a few years, passing away in 1983.

Though his career slowed in the 1970s, Fred Emney left behind a body of work that spanned stage, screen, radio, and television, delighting audiences for more than half a century. With his trademark monocle, larger‑than‑life presence, and gift for timing, he embodied a style of comedy that was both quintessentially British and uniquely his own.

Fred’s life was not without hardship, but his resilience, wit, and dedication to his craft ensured that he remained a beloved figure in entertainment. To colleagues, he was a consummate professional; to audiences, a familiar and comforting presence; and to history, a reminder of the golden age of variety and character comedy.

Published on September 25th, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.