The Key to Time

Review by Daniel Tessier

In 1976, Graham Williams, previously script editor on BBC series including Sutherland's Law, Double Dealers and Z-Cars, put himself forward for the position of producer on Doctor Who. Central to his application was a new vision for the series, one which would add a new layer of mythology to the programme's ever-growing universe. He won the position, taking over for the fifteenth season in 1977, but that season's scripts were already at too advanced a stage to incorporate his new idea. So it was held over for season sixteen, which was conceived as a single, overarching narrative: the quest for the Key to Time.

In spite of continuing the structure of the previous three seasons – five four-part serials and a six-part finale – season sixteen told a single, long story. Each individual serial was an adventure in its own right but tied into the ongoing search for a powerful cosmic artefact. At least, that was how Williams pitched it. In practice, most of the serials treat the Key to Time as an afterthought, clearly having already been plotted out before the story arc had been confirmed, with the overall plot rather bluntly attached at the beginning and end.

In itself though, the concept is an intriguing one, and one that lends itself to a serialised adventure narrative. Williams proposed that, above the Time Lords – the Doctor's own people who had become distinctly less mysterious and impressive as more had been seen of them – stood more powerful beings, responsible for overseeing the running of the universe. These are the White and Black Guardians, twin godlike entities who exist in opposition. This was, of course, already clichéd. Binary representations of good and evil recur in religions and folklore throughout the world and an array of fantastic fiction. Marking the former as white and the latter as black is perhaps the biggest cliché of all. However, what sets it apart is that neither Guardian is described as bluntly as being good or evil in Williams's initial conception. Instead, the White Guardian represents order, while the Black Guardian represents chaos; between them, the universe remains balanced.

The balance of the universe is maintained by the Key to Time, an object made from “the raw stuff of the universe” which is imbued with ultimate power. Anyone who had the Key in their possession would have power over everything, so it was broken into six pieces and scattered about time and space. Due to the Key's nature, the pieces could take on any form imaginable, making them all the harder to find. However, there are times when the universe threatens to become unbalanced, so it is necessary to rebuild the Key so that time can be stopped and everything rebalanced once again. Someone must be sent to gather the segments of the Key. Guess who the White Guardian has chosen to do the job?

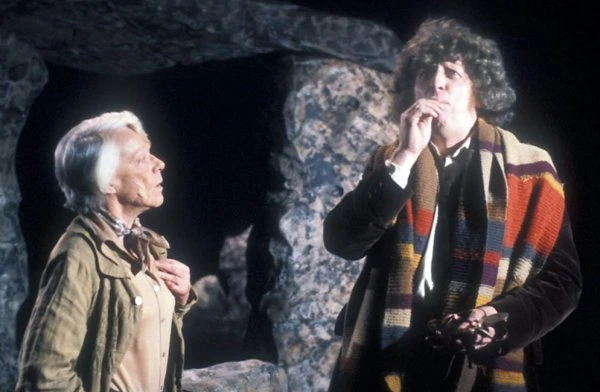

In the opening episode of The Ribos Operation, the White Guardian grounds the TARDIS, opens the doors and summons the Doctor out. He's played by Cyril Luckham (The Forsyte Saga, The Cedar Tree), sitting in a wicker chair, dressed in a white suit and a straw hat, looking like Colonel Sanders or Mr Kipling. It's unlikely that, were it made now, the story would present the ultimate authority, essentially the closest thing to God the series had presented, as the image of Anglocentric colonialism. Still, Luckham plays the part with a quiet, commanding presence, with even Tom Baker's unstoppable Doctor taken aback. This Doctor, the one the least able to respect authority, can't quite keep from being facetious, and tries to wriggle out of the cosmic quest, leading to perhaps the single best threat in the programme's history:

“You want me to volunteer, isn't that it?”

“Precisely.”

“And if I don't?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing? You mean nothing will happen to me?”

“Nothing at all. Ever.”

While the overall plot is applied pretty flimsily in some cases, it does give the Doctor an excuse to go looking for trouble and practically begs for him to visit as man far-flung places as possible. Of course, he can't be doing all this on his own, no matter how much Tom Baker likes to keep the show all to himself. As with the previous season, the Doctor is accompanied by his faithful robotic hound, K-9, voiced by John Leeson. In fact, this K-9 Mark 2, both on-screen and in real life, has been rebuilt between seasons so that during filming it actually obeys the remote control of its operator and no longer makes so much noise that it drowns out the dialogue.

Man's best friend isn't going to do the job on his own, however, so the White Guardian has assigned a new assistant to the Doctor. Mary Tamm (Brookside, The Hello Goodbye Man) stars in this season alone as the Time Lady Romanadvoratrelundar – Romana for short (it was that or Fred). Haughty, aristocratic, and rather full of herself, Romana is only a little over a hundred years old and fresh out of the Time Lord Academy. While her academic credentials put the Doctor's to shame, she has absolutely no experience in the wider universe. She has little time for the Doctor's histrionics, and he has equally little for her arrogance. It's well known that behind the scenes Baker was insisting he could carry the entire show without a co-star. It's also reported that Tamm didn't consider Doctor Who to be the most illustrious career move; she'd also been at RADA with her immediate predecessor as companion, Louise Jameson, who had warned her on the best way to stand up to Baker. When they meet in the season's opening episode, with the Doctor acting childishly uncooperative and Romana refusing to take him or anything very seriously, there probably wasn't too much acting involved.

After setting up the Doctor's quest and placing Romana on the TARDIS, The Ribos Operation can begin properly. Written by Robert Holmes, widely regarded as the best writer of the original Doctor Who series, it is easily the highlight of the season. The serial is a showcase for two of Holmes' hallmarks: inventive world-building and memorable double-acts. Romana, having been provided with a terribly handy tracer in order to track down the elusive segments, locates one on the remote planet Ribos. This planet has an eccentric orbit that leads to extremely long seasons, with Ribos, at the time the story takes place, many centuries into a harsh and unforgiving winter. Unlike most planets in Doctor Who in this period, Ribos is not a glossy futuristic world but one that is going through its own mediaeval age, on the cusp of a renaissance.

In some ways, the part of Ribos we see brings to mind Westeros from the much later Game of Thrones books and television series, albeit without the horrendous level of violence. We only see a small part of the society, but it is clearly one rich with ritual and history, brought to life with some stunning costumes and sets (some of the latter having been cribbed from the 1977 adaptation of Anna Karenina), evocative of mediaeval Russia. Winter has fallen, making life harsh for the population, with the nobles and their guards, the shrieves, living in more comfort than the commoners, and punishment for going against tradition and authority is harsh. There's even a dragon, of sorts; the shrievenzale, a lizard-like guard dog, that is mercifully glimpsed only briefly but provides this story's obligatory monster content.

It's a shame that we don't see many of the natives of Ribos, with only three locals having speaking roles. Prentis Hancock (Spy Trap, Space: 1999) makes the last of four Doctor Who appearances as the resolute Shrieve Captain, while Anne Tirard (Rogues Gallery, Within These Walls) gives a wonderfully arch performance as a mystic Seeker. Most memorable, though, is Binro, played with great sympathy and pathos by Timothy Bateson (The Bellcrest Story, Grange Hill, and a great many voice roles). Every society has to have its Galileo, or perhaps Giordano Bruno, who like Binro, claimed that the stars were suns in their own right, orbited by worlds of their own. Binro has been exiled for his beliefs, left crippled and forced to beg for a living. (Compared to Bruno, who was burned at the stake by the Catholic Church, Binro got off fairly lightly.) A scene in the third episode, where Binro learns that he was right about other worlds, is beautifully played.

While we don't meet many of the people of Ribos, their society is sketched in effectively and with a lightness of touch, much as the greater galaxy of which they have no knowledge. Arriving on the planet is the Graff Vynda-K, played with oily arrogance by Paul Seed (The Double Dealers). Looking to purchase the planet as a base in his own quest to retake his throne of the planet Levithia in the Greater Cyrrenhic Empire, the Graff arrives with a phalanx of troops led by his grizzled right-hand-man Sholakh (Robert Keegan – Beryl's Lot). The Graff and Sholakh display a mighty devotion to each other, even as the warlord's sanity deteriorates as the story develops, all played with great conviction by Seed and Keegan.

Selling Ribos to the Graff is Garron, a galactic con artist from Hackney Wick, played by the incomparable Iain Cuthbertson (Budgie, Sutherland's Law, Children of the Stones). Switching between plummy tones and cockney wideboy stylings, Garron is a wonderfully charismatic criminal, running a grand con in the classic style of selling Tower Bridge to wealthy tourists, except that he does it with whole planets. The viewer absolutely wants Garron to win in his swindling of the Graff, thanks to the Holmes's knack for characterisation and Cuthbertson's irresistible performance. (Cuthbertson would be one of several actors considered to take over from Baker as the Doctor five years later, and would work on another Williams production, Super Gran, as “the Scunner Campbell.”)

Aiding Garron as sidekick, wingman and dogsbody is Unstoffe, a rare on-screen performance by Nigel Plaskitt, a prolific voice artist and puppeteer best known for Pipkins. Unstoffe walks through several dangerous roles in the con thanks to his trustworthy face, a vital asset in the con artist trade. The icing on the cake for the Graff is a large lump of a valuable mineral by the peculiar name jethrik, essential for the star drives of the Empire, which has been planted by Garron to make his planetary deals irresistible. It also happens to be the disguised first segment of the Key to Time...

Holmes's scripts for The Ribos Operation are among his best. Not only does he combine his usual excellence in humour, character work and subtle world-building, but he also creates a layered story where events on the grandest scale are echoed downwards to the most human level. The overarching cosmic conflict between the White and Black Guardians is reflected in the endless battle between the Ice Time and Sun Time on Ribos, supposedly caused by battling gods but in reality, the result of the planet's orbit. The galactic conflict within the Cyrrenhic Empire is echoed by the smaller but no less bloody incursion by the Graff upon the city of Shurr. Even the conflict between science and superstition, be it that of the people of Ribos as they struggle to make sense of their world, or the Graff's single-minded belief in his divine right to rule, is suggested to be an echo of the greater battle between order and chaos. And, while science and rationality are shown to be the way forward, the Seeker's visions, the power of the Guardians and the very existence of this symmetry suggest there is more to the universe than what we can understand. It's a truly brilliant script realised by some excellent performances. Unfortunately, the rest of the season can't quite live up to the standard set by its first story.

The second serial, The Pirate Planet, doesn't stand out nearly so much, in spite of an amazing pedigree. It's the very first Doctor Who contribution by Douglas Adams, best known, of course, for The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Indeed, Adams was writing the scripts for The Pirate Planet and the first Hitchhiker's radio series concurrently, so it's not at all surprising that they have a similar style, even down to versions of the same jokes. Adams is also unique in being the only person to have written for both Monty Python and Doctor Who, and there are certainly scenes of The Pirate Planet that have a certain Pythonesque bent to them.

The serial starts with the tracer directing the TARDIS to the planet Calufrax, with Romana doing the honours and piloting the ship by the book. When they materialise, they are not on the cold and lifeless world of Calufrax but Zanak, a rather nice planet at first glance, where occasionally the ruler of the world, the Captain, announces a new age of plenty and precious stones rain down from the sky. This is all rather inexplicable, and it isn't long before the Doctor and Romana's investigations land them in trouble. The Doctor finds himself with a family looking after a young man named Pralix (David Sibley – The Manageress, A Family Affair) who is beset by fevers and visions since the last age of prosperity was announced. Coming for him is an army of zombie-like psychics called the Mentiads, who have terrible powers.

Romana soon finds herself taken to the bridge – the Captain's stronghold at the summit of a mighty fortress. The Captain is a deranged cyborg, played with maniacal glee by Bruce Purchase (Return to Treasure Island, Clayhanger). Really, it's a performance that has to be experienced, with Purchase rolling his one visible eye while extolling baffling proclamations and oaths: “Moons of Madness!” “By the bones of the Sky Demon!” and so on. Viewers might find themselves voicing such peculiar expressions in a booming voice for days after watching. In spite of delivering a contender for the hammiest performance in Doctor Who (which is really saying something), there are moments where the Captain is quieter and more genuinely tormented, hinting at greater depths to his character that we'll only discover later. Aiding him are the long-suffering Mr Fibuli (an entertaining performance by Andrew Robertson – Oil Strike North) and the Captain's nurse (a rather one-note performance by Rosalind Lloyd – A Question of Guilt). Oh, and he has a robot parrot that kills people, you know, for the kiddies.

The Pirate Planet has a script that is absolutely bursting with ideas, from a machine that saves your legs by moving you by removing inertia; to its central concept, Zanak, a hollow world which beams across the galaxy swallowing other planets and plundering them for their mineral resources. Everything is linked together with gradual revelations making the bizarre truth gradually clear. The cliffhanger ending to part three, sees the Doctor forced to walk the plank to a kilometre-long drop. The resolution to this is completely out of nowhere and turns our understanding of the story and the identity of the villain on its head.

Yet, it's very much an obvious first adventure script by a writer who is on the cusp of becoming great. Watching it, it's hard to escape the feeling that Adams was trying to cram every possible thing he could think of into the story in case he never got another go. What he doesn't handle well is the pacing, which is damaged by interminable scenes of Mentiads wandering across fields and quarries, and the dialogue. Basically, Adams already excelled at jokes, but hadn't really got the hang of serious dialogue yet. As such, Hitchhiker's, while being similar in style and content, works better than The Pirate Planet by being a string of jokes and bizarre situations, without having to worry too much about stakes and a coherent plot. Late in the day, the Captain announces his next target for plunder will be Earth, an unnecessary attempt to try to make the threat of Zanak more immediate. Kimus, a tag-along hero played with some charisma by a young David Warwick, is saddled with lines like “Bandraginus Five, with every last breath in my body you will be avenged!” and somehow manages to do it with a straight face, which is a pity, because the good stuff here is really good. Some of the lines are absolute classics, the best perhaps being the Doctor's verbal assault on the Captain: “You don't want to take over the universe, do you? No, you wouldn't know what to do with it, beyond shout at it.” Baker is on form, balancing the Doctor's righteous anger with his usual tomfoolery. He manages to own scenes with Purchase, which is no mean feat, and isn't even held back by a very visible injury to his lip (which happened when Paul Seed's dog bit him during the filming of The Ribos Operation). Tamm puts in a stronger performance now that Romana gets to be a little more competent and actually use her knowledge. They make a great team here.

Hard as it may be to imagine, earlier drafts of the script were even busier, with even more outlandish ideas thrown in. At various points, the story involved a machine that absorbs aggression from its victims; the involvement of the Master's daughter, targeting planets where her father had been defeated; and the segment being the entire continent of Africa (the segment's actual identity here is rather ingenious). The season's script editor Anthony Read worked closely with Adams to bring the story under control, in effect working as acting producer while Williams was recovering from an injury. Nonetheless, the powers that be were clearly impressed with Adams; when Read left the position he recommended Adams for the role of script editor, which he took up for this season's final serial and the whole of season seventeen.

The third serial of the season, The Stones of Blood, is a charming and picturesque story that combines cosy rural chills with imaginative science fiction. The first of two scripts this season by David Fisher (Crown Court, Mogul), it also happens to be the hundredth Doctor Who serial, and almost coincided with the programme's fifteenth anniversary. To mark the occasion, a scene was devised in which Romana and K-9 surprised the Doctor with a birthday party, complete with a present: a new, identical scarf. Williams decided this was too self-indulgent and vetoed the scene; at least the cast got to have some cake.

The Stones of Blood itself isn't quite that cute, but it's not far off. After a quick recap on the nature of their quest for anyone who hasn't been watching (or paying attention) over the previous eight weeks, the Doctor reveals to Romana that it wasn't the Time Lord President who sent them on the mission, but the White Guardian himself. Tamm's spectacularly incredulous “Hwwhat?!” is unforgettable. Thankfully, things get better quickly as they head to Earth to find the third segment. Arriving in contemporary Cornwall, they soon meet the delightfully eccentric Professor Emilia Rumford and her, ahem, friend Vivien Fay, who are studying a Stonehenge-like ring of standing stones. Beatrice Lehmann (Love for Lydia, The Portrait of a Lady) is the highlight of the serial as Professor Rumford, an enthusiastic old girl with strong opinions on anything you could ask her. Lehmann, aged 74 and with decades of theatre experience behind her, was reportedly as entertaining off-screen as on. She particularly shares great chemistry with Baker in this serial, enough to make you wonder why they didn't just let him have an old lady companion to charm into the TARDIS. Sadly, it was Lehmann's last role before she passed away the following year, although her appearance in Crime and Punishment was broadcast after.

Susan Engel (The Cedar Tree, The Lotus Eaters) gives a classy and vivacious performance as Miss Vivian Fay, owner of the land on which the stones stand and whose family go back centuries in the area. A family of formidable women, whose husbands seem to meet unfortunate accidents, and whose portraits have all been hidden in the opulent Boscombe Hall. More immediately insidious, it would appear, is Mr de Vries, leader of the local Druidic sect, played with sneering gusto by Nicholas McArdle (Strathblair). De Vries lives in the Hall and is fond a bit of blood sacrifice, worshipping a Celtic goddess named the Cailleach.

De Vries is merely a stooge, however, and the Cailleach is very real. It should come as no surprise that Miss Fay is not what she seems, and is, in fact, the goddess herself (although Cailleach, Gaelic for hag or old woman, is a rather harsh thing to call Susan Engel). Except that is merely another in a long line of alter egos; she is actually Cessair of Diplos, an alien criminal whose been on the lam for the last four thousand years. This all sounds like Doctor Who by-the-books, but it's her alien servants that really make it: the standing stones are themselves silicon-based life forms, the bloodthirsty Ogri, who feed on haemoglobin and to whom the sacrifices are made.

On paper, vampiric standing stones is a fantastic idea, bizarre and unnerving. On screen, it doesn't quite work. Respect to them for trying, but big polystyrene slabs shuffling past windows and having ray battles with K-9 don't really summon the level of horror intended. Even this pales in comparison to the cliffhanger ending to part two, in which Engel, painted silver, blasts Romana into hyperspace, leading to a second half that ups the sci-fi considerably. Adjacent to the stone circle in a higher set of dimensions sits a spaceship, on which the Megara, two glittery computer intelligences, have been waiting patiently for someone to bring their prisoner back. Unfortunately, the Doctor and Romana unleash these two prissy AIs, who promptly put the Doctor on trial for breaking into the ship. Meanwhile, Cessair/Fay still holds the all-powerful Seal of Diplos, the theft of which has made her a fugitive across space. Just guess what the segment is disguised as...

It's not the most logical of scripts and the ending is dreadfully rushed, but the idea of two computers acting as judge, defence and prosecution, while the accused desperately fight against their ingrained bureaucracy and tries desperately to point out that the actual villain is standing over there, is even more Douglas Adamsesque than this own script. When combined with killer menhirs, dotty old historians and lashings of sapphic undertones, it's irresistible. It doesn't get much more Doctor Who than that.