The Tomb of the Cybermen

Few Doctor Who stories enjoy the near-mythic reputation of The Tomb of the Cybermen. Long considered lost and then triumphantly recovered from Hong Kong in 1991, its rush-released VHS became the best-selling Doctor Who title to that date—proof that its legend had only grown in absence. Watching it today, it is not hard to see why this third Cyberman appearance in a single year has been so frequently hailed as one of the programme’s finest achievements.

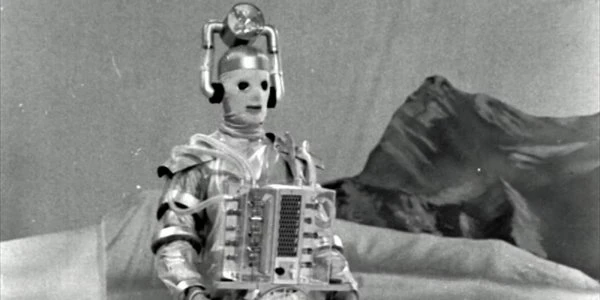

By the time The Tomb of the Cybermen entered production in 1967, the Cybermen had very quickly proven themselves to be one of Doctor Who’s most successful monster creations. Introduced only the previous year in The Tenth Planet, they had made an immediate impact—not least because that story featured the First Doctor’s regeneration. Their unsettling design, emotionless voices, and chilling logic distinguished them from more conventional “bug-eyed” monsters. Unlike the Daleks, whose rage was overt and explosive, the Cybermen were cold, clinical, and disturbingly human in origin: a race that had sacrificed flesh and feeling for survival.

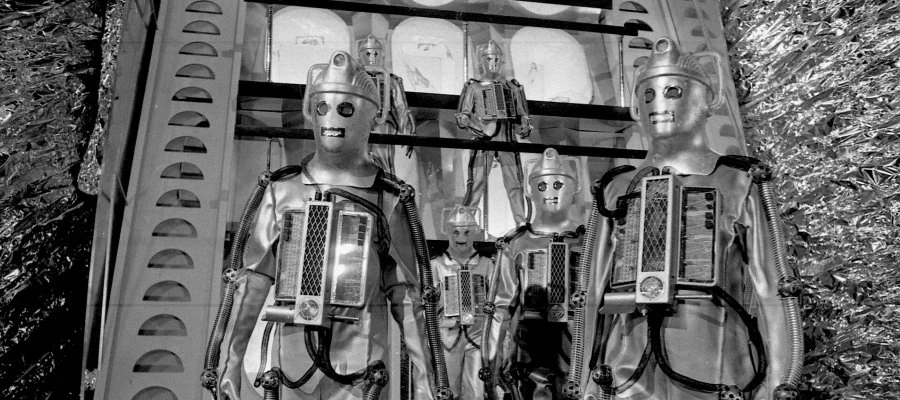

Their first return, in The Moonbase, reinforced their popularity. The design team refined and reinforced the Cybermen’s appearance, and this updated look was retained for The Tomb of the Cybermen. As the programme evolved, the production increasingly emphasised the Cybermen as stark, industrial entities who had eradicated every vestige of humanity. The revised design reflected that shift. By the time of Tomb, they appeared less like modified people and more like uniform, mechanised enforcers—an aesthetic that would define their enduring visual identity.

Appearing twice within a short span had already elevated them to the status of recurring arch-enemies, and audience reaction indicated that they were creatures viewers wanted to see again. They were visually distinctive, dramatically flexible, and—importantly for a series that relied on memorable antagonists—instantly recognisable. In an era when Doctor Who was still defining its rogues’ gallery, the Cybermen were rapidly becoming second only to the Daleks in cultural footprint.

From a production standpoint, there were practical motivations as well. The Cybermen were an in-house creation (unlike the Daleks, whose rights were more complicated), making them easier to reuse. Their mythology was still relatively underdeveloped, offering fertile ground for expansion. Their creator, Kit Pedler in particular, was keen to deepen their backstory rather than simply stage another invasion plot. The result was a conscious decision not merely to revive a popular monster for ratings security, but to reposition them within a more atmospheric and historically textured narrative.

Pedler, fascinated by Egyptian archaeology at the time, wanted to explore the Cybermen’s past, and the result was a striking concept: the Cybermen entombed like pharaohs in a frozen necropolis on Telos—their “new” home planet, first alluded to in cut dialogue from The Moonbase. With working titles such as The Ice Tombs of Telos and The Cybermen Planet, the story embraced a deliberately claustrophobic atmosphere. Pedler’s relative inexperience meant Gerry Davis had substantial input into shaping the script, but together they crafted a tightly structured four-parter built around confinement, secrecy, and hubris.

Set roughly five centuries after the Cybermen’s last recorded activity (placing events around 2570, given their 2070 assault in The Moonbase), the story opens immediately after The Evil of the Daleks. The Doctor, Jamie, and Victoria arrive on Telos and encounter an archaeological expedition funded by the imperious Kaftan and led in practice by the ambitious Klieg, accompanied by Kaftan’s servant Toberman. The tomb they seek belongs to a race believed extinct for five hundred years.

The opening episodes thrive on atmosphere. The electrically sealed doors, the geometric corridors, and the stark, icy interiors create one of the most impressive set designs of the 1960s era. When the expedition finally breaches the inner crypt and reveals rows of frozen Cybermen, the imagery is unforgettable. The cliffhanger to episode two—in which the Cybermen awaken and break free of their tombs—remains one of the most celebrated in the show’s history.

The narrative then pivots to betrayal. Kaftan and Klieg intend to ally themselves with the revived Cybermen and use them to conquer the universe. Their delusion is short-lived: the Cybermen have no interest in partnership, only domination. They plan to rebuild their invasion force and resume their campaign against Earth. The human conspirators’ arrogance becomes their undoing, particularly Klieg’s fanatical refusal to accept that the Cybermen will not share power.

The Cyber-Controller, physically portrayed by Michael Kilgarriff (with Peter Hawkins providing the modulated voice), is a commanding presence—coldly logical and faintly amused by human folly. Kilgarriff would later return to the role in Attack of the Cybermen, this time supplying the voice himself. The Cybermen here are at their most iconic: silver giants emerging from ice, implacable and eerily patient.

Yet the story’s emotional heart lies not in its villains but in Patrick Troughton’s Second Doctor. His performance balances whimsy and gravity with extraordinary subtlety. A quiet scene in which he comforts Victoria about her grief is often cited as one of the most moving moments in classic Doctor Who, revealing a depth and compassion sometimes hidden beneath his clownish exterior. Frazer Hines and Deborah Watling are strong throughout, grounding the fantastical elements in humanity.

The supporting cast also leave an impression. George Pastell’s Klieg exudes obsessive zeal, while Shirley Cooklin’s Kaftan is cool and calculating. Roy Stewart’s Toberman plays a pivotal role in the climax: captured and conditioned by the Cybermen, he ultimately breaks free and sacrifices himself to destroy the Cyber-Controller, electrocuting them both as he completes the circuit that seals the tomb once more. It is a powerful ending, though the character’s largely servile portrayal—combined with the casting of a Black actor—has drawn justified criticism from retrospective commentators for perpetuating uncomfortable racial stereotypes.

Elsewhere, Aubrey Richards brings a measured authority to Professor Parry, the expedition’s nominal leader, while Cyril Shaps gives John Viner an air of nervous pragmatism as Parry’s loyal assistant. George Roubicek’s Captain Hopper provides grounded resolve as the expedition’s pilot, and Bernard Holley’s Peter Haydon contributes to the sense of a professional, if increasingly imperilled, team.

Even in its day the story was not without controversy. Some viewers felt it was excessively violent, particularly a moment when fluid spurts from a damaged Cyberman. Nevertheless, BBC Head of Drama Sydney Newman personally congratulated producer Peter Bryant after the first episode aired, and many within the corporation recognised the serial’s quality.

Technically accomplished, dramatically tight, and visually striking, The Tomb of the Cybermen endures because it understands the Cybermen’s core appeal: not just as monsters, but as relics of a fallen civilisation waiting to rise again. Its closing image—unseen by the departing characters—of a surviving Cybermat creeping toward Toberman’s body offers a final, chilling suggestion that evil is never entirely entombed.

The Tomb of the Cybermen remains a landmark: a masterclass in atmosphere, a showcase for Troughton’s Doctor, and a story whose resurrection in 1991 fittingly mirrored its own theme of something thought lost returning from the icy darkness.