Joan of Arc

1999 - CanadaJoan of Arc is a problem - for theologians, for psychiatrists, and for writers. Did she really have Visions from the Saints telling her to drive the English out of France? If she did, the challenge for the theologian is why the Saints should favour one nation over another when both were of the same religious denomination? If she did not, the challenge for the psychiatrist is to explain how a psychotic could achieve what Joan did.

For the greatest difficulty in writing her off as a charlatan or a madwoman, or both, is that she really did drive the English out of France - or at least began the process. A seventeen-year-old peasant girl in a particularly class conscious and masculine culture, she made a dangerous journey across France to ask King Charles VII, then styled merely as the Dauphin, for command of an army - and she got it. She then led it to raise the Siege of Orleans and win the Battle of Patay. Although the Hundred Years War was to continue for some time, that was the turning point. Before Joan's intervention, the tide had been running with the English and their Welsh auxiliaries since the Battle of Agincourt, but they never recovered the momentum after Patay.

With their usual gift of hindsight, historians point out that there were also other factors at work, including the divided English command structure and a talented generation of French commanders who did the actual leading in "Joan's" army. All this is true, but Joan herself was the decisive factor. She convinced first the Dauphin and then the French soldiers that they could beat the previously unbeatable English. It is no wonder that, even if they disagreed about the actual source, her contemporaries all agreed that her power was Supernatural, or at least supernatural, in origin: those who said it was small-s supernatural burnt her as a witch; those who said it was big-S Supernatural later had her canonized as a Saint herself.

It is also no wonder that her story has been fertile ground for writers of all sorts ever since. Joan has been the subject of countless songs, operas, plays, and films. The most notable of the plays is George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan, which has been adapted for British television in 1951 with Constance Cummings, 1958 with Siobhan McKenna, and 1968 with Janet Suzman, and for American television in 1967 with Genevieve Bujold. The benchmark cinematic film is the 1948 Hollywood epic 'Joan of Arc,' directed by Victor Fleming, with Ingrid Bergman in the title role.

The challenge for the writer is whether to take a reverential line or a cynical one. Shaw tended to the cynical, even if he was respectful towards both Joan and her opponents. The 1948 film was reverential, as was a memorable 1982 music video by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark.

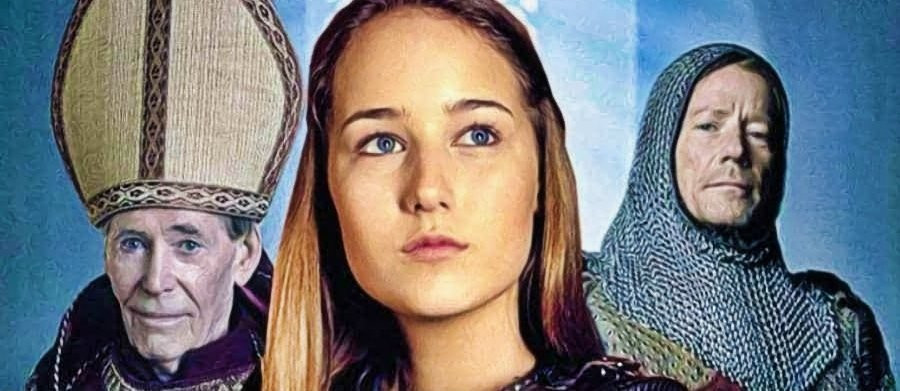

Then in 1999, two large scale English language screen productions came along more or less at once: this sort of synchronicity in production is actually quite common, as if an idea is in the air at a particular moment in time. The first, the subject of this review, was another Joan of Arc, this time a Canadian-produced, but essentially very American, television "miniseries" with Leelee Sobieski as Joan.

Later that year came a full dress feature film, 'The Messenger: the Story of Joan of Arc,' directed by Luc Besson, with Milla Jovovich as Joan and John Malkovich as Charles VII. It has been interesting to watch or rewatch both sequentially as part of the review process because they take fundamentally different approaches.

Where the "miniseries," for obvious commercial reasons, stays at the reverential end of the spectrum, Besson has the freedom to take a more subversive line. In the end, Besson's strategy does not really work as well as the more traditional storytelling - he tries to be too clever by half - even if the feature film is generally of much higher quality than the "miniseries."

Both productions have strong supporting casts, but Besson gets more out of his players. His characters are well rounded, credible, and grown up. By contrast, the talented actors in the "miniseries" are given little more than caricatures: they do remarkably well with their parts but we never feel we are watching real people, never mind the actual historical characters. Although the Besson film departs too much from history on a number of very important points, it is still in general far more accurate than the "miniseries." Its battle scenes, far more visceral than would ever be allowed on network television at this time, are horribly believable.

The writing and direction of the "miniseries" are, on the whole, pretty dire. It is a surprise to see the name of Ronald Parker, who later went on to co-write the excellent Hatfields & McCoys, credited as one of the writers here. It can only be said that he must have got a lot better.

The script could actually be used as the basis of a deliberate satire on Hollywoodisms. Every bad cliché imaginable is present - characters shouting "Nooooo!" when other characters are killed, religious experiences conveyed by bad CGI lights from the clouds and loud music, etc. Indeed, the loud musical cues are fairly constant, part of an attempt to ram in as many cheap emotional moments as possible which succeeds only in undermining the emotional impact of the story as a whole. The dialogue has no ear for history, and every aspect of an expensive production lacks all sense of time and place. It is a poorly educated West Coast hack's notion of Medieval France, more California than Champagne, more Los Angeles than Lorraine.

The whole aesthetic is very 1990s. Everyone is good looking and everything is clean. There is a definite frisson between Joan and the handsome squire deputed to escort her. It feels more like an episode of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys than a religious drama

And yet...

The unique selling proposition of the "miniseries" is that Sobieski was the youngest person to play Joan in a major production. She was in fact slightly younger than Joan herself. This works.

Sobieski gives a self-confident performance, even if it now seems more redolent of 1990s "girl power" than anything vaguely historical. In fairness, this may be due to the way the part is written rather than the way it is played, the producers obviously being eager to attract the young female demographic. Sobieski Joan therefore sometimes comes across as a bit surly, and occasionally sanctimonious rather than sanctified. Historical Joan could also be bossy - one of the things that got her into trouble - but she balanced this with a degree of humility and deference in keeping with her place in the times in which she lived. Here she just seems a bit of a precocious know-it-all.

However, the character's lack of self-perception actually works in her favour because it reminds us that this is still a very young girl, immature and deeply unsure of herself beneath the surface bravado. We feel a sympathy for her we might not feel for her with a more experienced actress in the role, especially when she stands alone against a crowd of fully grown men.

It is no coincidence that the "miniseries" was made soon after the start of Buffy the Vampire Slayer on television. Joan of Arc was the Proto-Buffy, both the pre-feminist role model who showed that a young girl could do great things even in a culture which did not value young girls and the self-sacrificing hero who finds strength in her vulnerability. Although Sobieski lacks the breadth of a Sarah Michelle Gellar, she shares much of the same appeal.

So even when the story is told badly, it is hard not to be moved when this brave teenager succeeds against incredible odds and then faces horrors that would terrify a much older person. We come to care about her more than we do about more contrived Joans.

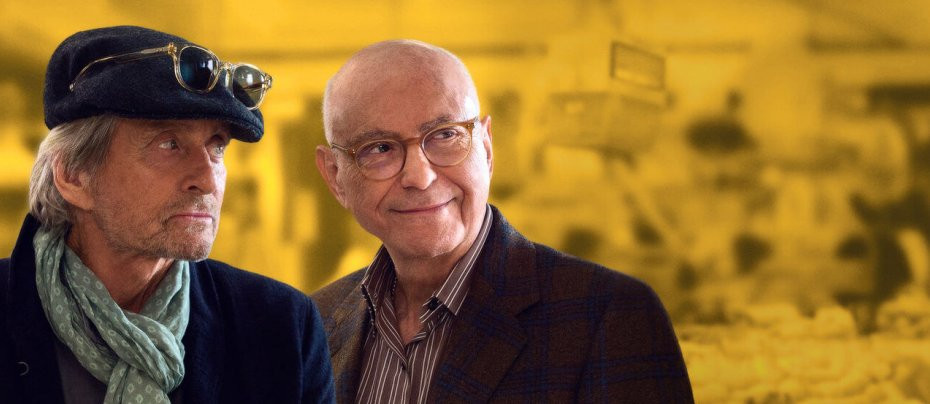

Neil Patrick Harris enjoys himself playing the Dauphin as a Machiavellian schemer - more like the future Louis XI, "the Spider," Charles VII's son, than Charles himself. Powers Boothe and Jacqueline Bisset add substance to Joan's parents, even if they are given little to do. Robert Loggia, as the Curate of Joan's home village, gives some clunky exposition more dignity than it deserves. Maury Chaykin is fun as the local garrison commander whom Joan approaches first. Peter O'Toole does his best with a positively anti-historical version of Bishop Cauchon, and at least gets one good scene with the ever classy John Standing which only shows the standard to which the whole thing might have aspired.

The veteran commander La Hire is portrayed very effectively by Peter Strauss, himself the veteran of many a "miniseries." For some reason La Hire is often played as foul-mouthed comedy relief - very ably played by Ward Bond in 1948 and Richard Ridings in the Besson film, Strauss plays him straight as the formidable soldier he was, but the fascinating relationship between Joan and the professional commanders who gradually became genuinely devoted to her, and who really did try to rescue her from the stake, is never explored properly. It was a missed opportunity in particular not to introduce the innocent Sobieski character to Gilles de Rais - Vincent Cassel in the Besson film - whose passionate support for the historical Joan won him a Marshal's baton in his mid-twenties but who later became the most notorious serial murderer in French history. A frisson between those two might indeed have been intriguing...

As it is, "missed opportunity" sums up the whole project - yet another example of a powerful true story and a good cast let down by a script with no grasp of history.

Review by John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 9th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.